This essay was originally published as part of a submission for David Perell’s Write of Passage programme.

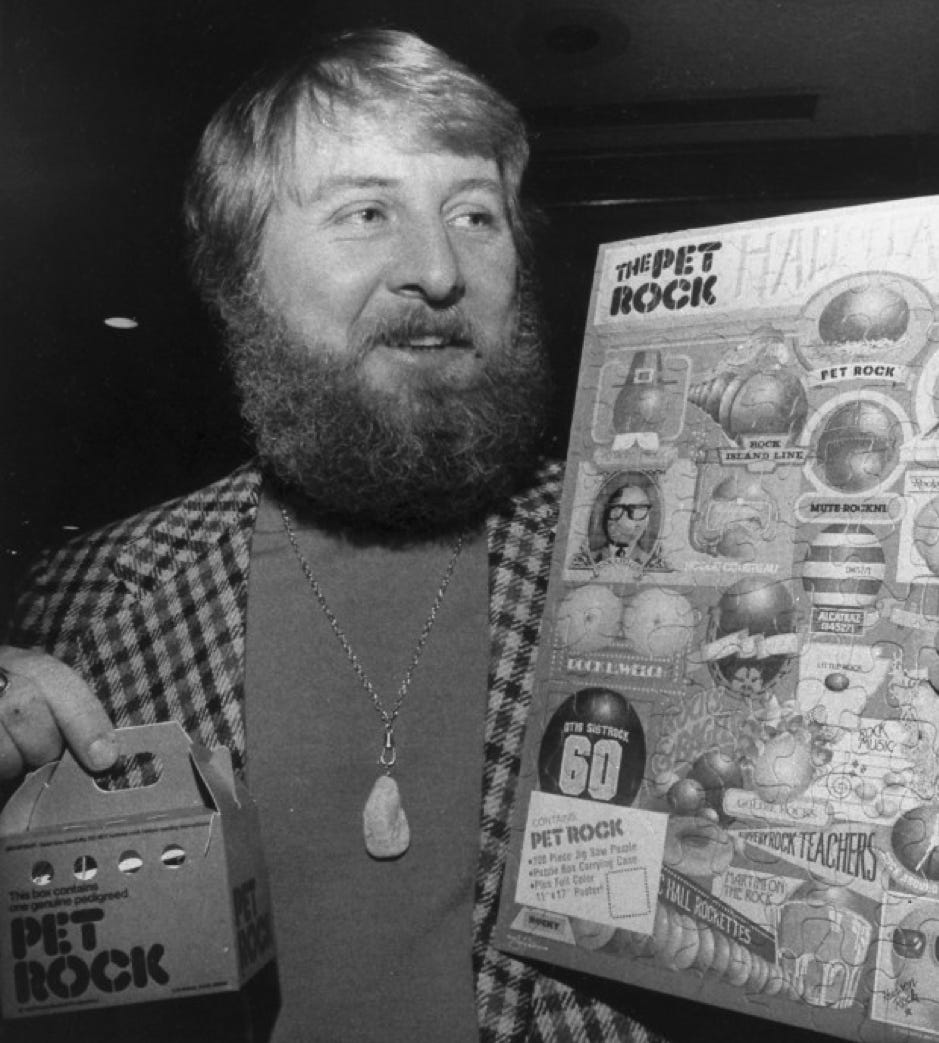

Gary Dahl was certain he had found an upgrade on man’s best friend.

As he savoured gulps of lager at a local bar in his hometown of Los Gatos, California, he conceived an idea that would forever be ingrained in the groovy nostalgia of 1970s Americana.

Per the oft repeated lore, his comrades at the time were embroiled in animated dialogue about the mishaps and misadventures of their various pets. Their respective dogs, cats, birds and hamsters stood accused of being vacuums of attention and agents of chaos. They required round-the-clock maintenance, and demanded total fealty from their owners.

Dahl - though critter-less at the time - was eager to contribute to the discussion. He boasted that his own beastly buddy required none of the subservience that seemed to ail his compatriots. He said he had a pet that didn’t need to be fed, cleaned, groomed or entertained. It would not get sick, it would not disobey, it would not die.

His friends were curious to hear more about this apparently perfect pet. As they leaned closer, expecting to be regaled with tales of some fantastically tame impala, Dahl came clean.

“I have a pet rock,” he said with a grin, revealing his charade.

As he proudly soaked in the lukewarm bath of his punchline, he had unwittingly provoked a very serious conversation about the merits and shortfalls of a theoretical pet rock. After a round of lively debate, the party concluded that - for all the exact reasons that Dahl had joked about earlier - a pet rock would indeed be the ideal companion.

When the tabs were settled for the night, the group dispersed, bleary-eyed, back to their own homes. For Dahl, the evening was just getting started.

While the others had filed the pet rock debate away the same way you might do with other hall-of-fame bar conversations like “would you rather have the ability to teleport or fly?”, Dahl had seen a thread worth tugging on. His curiosity wasn’t just aroused, it was ready to climax. As an advertising executive (and at the time a freelance copywriter) he had seen opportunity when others had seen silliness.

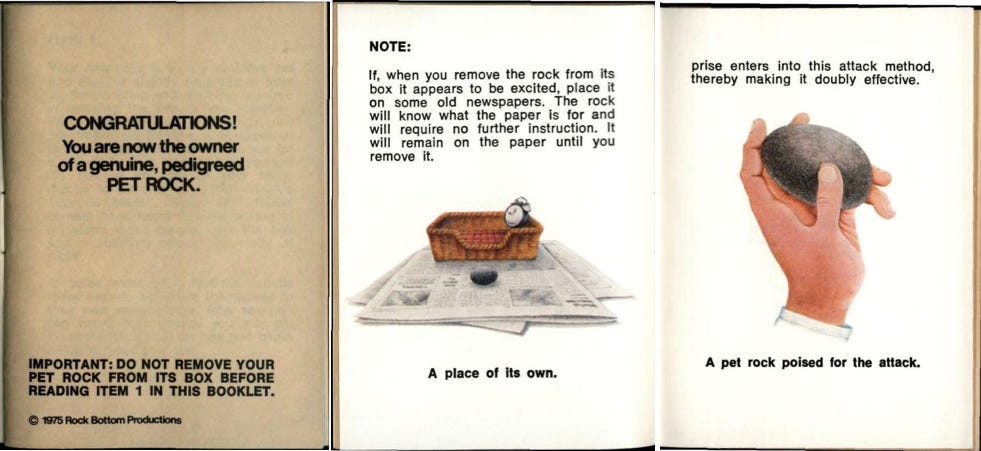

After returning home that evening, he began drafting a whimsical instruction manual for would-be owners of his fictional pet rock. In the subsequent weeks, he found a local gravel supplier from whom he bought a stockpile of handsome stones. These smooth, grey, egg-shaped stones had been gathered from Rosarito Beach on the Pacific coast of Mexico. Dahl also designed a portable cardboard box (complete with ventilation holes) and lined it with a nest of straw shavings so that his ‘companions’ could travel comfortably.

Four months later, at a gift show in San Francisco in August 1975, the Pet Rock made its official debut.

By the time he had finished with his roadshows on the East Coast, the Pet Rock was a national sensation. Iconic department stores were clamouring to stock his product. He appeared on The Tonight Show. Twice. Three in every four newspapers in the US covered his story. He even snagged a feature in the dignified pages of Newsweek, where his invention was referred to as “one of the most ridiculously successful marketing schemes ever”.

The real clincher wasn’t the Pet Rock, however, it was the cheeky 32-page instruction manual that came along with it. The little pamphlet helped to bring his idea to life, like a miracle of marketing alchemy. It also allowed Dahl to flex the full range of his copyrighting talents. Titled The Care and Training of Your Pet Rock, the manual contained a litany of jokes, puns, and commands to properly raise your geological companion. It included training tips to help your Pet Rock learn how to come (difficult), stay (easy), roll over (best done on a hill) and play dead (a speciality). The guidebook allowed him to conjure meaning where there wasn’t any before, a virtue consistent with any well executed marketing campaign.

Because he launched the product in the run up to the holiday season, the Pet Rock collided head-first with the hordes of holiday shoppers in the US looking for the perfect novelty gift. The appeal was evident in the rabid demand that followed.

In October, he was shipping 10,000 Pet Rocks every day.

By December, this number had run up to 100,000 per day.

By the time Christmas came around, he had sold two and a half tons of Pet Rocks.

Given that the Rocks cost him just 5 cents to manufacture and retailed for $3.95, Dahl had stumbled into a deliciously lucrative enterprise. His idea would spawn an entire cottage industry of accessory products for Pet Rocks that included clothes, jewellery, cemeteries, training schools, music singles, and even college degrees ($3 for a bachelor’s, $10 for a PhD).

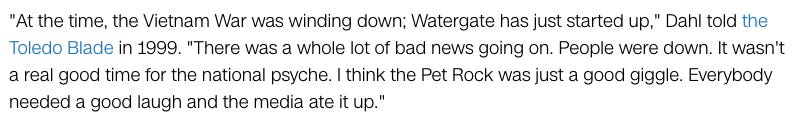

As the calendar flipped over to 1976, the enterprise eventually lost steam. Predictably, fashion had moved on. Pet Rocks had been discarded into the ‘Former Fad’ scrap heap. They joined other viral products like the Hula Hoop and the Slinky that had similarly invaded the American retail zeitgeist for a brief spell in the limelight. But by then its creator had long sailed into the sunset.

In just a couple of months, Gary Dahl had managed to sell close to 1.5 million Mexican beach stones. His Pet Rocks had made him a millionaire, practically overnight. He set up his own novelty gifting company called Rock Bottom Productions (where the receptionist would answer the phone with “Hi, you’ve reached Rock Bottom”). Eager to prove he wasn’t a one hit wonder, he would later attempt to replicate his original playbook with other gag gifts like the ‘Official Sand Breeding Kit’ (self explanatory) and ‘Canned Earthquake’ (a coffee can with a wind-up mechanism that caused it to jump around on a table). Neither would capture the imagination like his original Pet Rock.

Decades later, it is tempting to tut-tut the consumers of the 70s for succumbing to such a brazen demonstration of marketing magic. But Gary Dahl was no huckster. He wasn’t trying to separate people from their money by some devious sleight of hand. He was trying to create the kind of the product for the kinds of people that needed it.

Dahl succeeded in packaging a sense of humour for a very bored public. He didn’t have to create a market for Pet Rocks. It was already there. His job as a marketer was to find the audience that was already open to the idea of Pet Rocks. He didn’t need to convince the whole of the United States that Pet Rocks weren’t stupid. He just needed his message to reach the kinds of people that would find humour and companionship in the company of a two-inch grey stone. That market may not have been 300 million people. But it was 1.5 million people. And that was enough.

In modern parlance, writer and marketer Seth Godin describes this as the ‘smallest viable audience’. It is the idea that your job as an entrepreneur or a creator is not to tailor your offering for a broad swathe of the population (which would in fact make you a shitty tailor). No, your job is to find the people that are already looking for the thing you’re offering, and let them know that you can offer something better than what’s out there. You need “the smallest viable audience, not the biggest possible audience." Godin writes that:

“Specificity is the way” - and that doesn't just apply to Pet Rocks.

James Dyson didn’t have to coerce people to come around to the idea of luxury vacuum cleaners. There were already people willing to spend top dollar on high-quality household appliances. But before Dyson came along they had nothing to spend their money on.

JK Rowling didn’t have to convince people to read about wizards. She just had to write a story that would tap into our pre-existing appetite for magic, and wait till we found it.

GoPro didn’t have to explain why they were making dynamic action cameras for people on the move. A legion of surfers and skateboarders already knew why it would be useful to have high quality cameras that were both portable and durable. They lived their lives in perpetual motion, and finally there was a product that allowed them to capture it. GoPro didn’t need the mass market to buy into their mission in order to be successful. They knew exactly who they were targeting.

Having a specific audience in mind is only a constraint in the way that a bullseye on a dartboard is a constraint. Everyone is never going to be the audience for your product, just like you are not the audience for everyone else’s product. Or movie. Or advertisement. Or restaurant.

Or essay.

I’ve been writing online for three years. It took me a long time to realise that I didn’t need the entire Internet to read my stuff. I just needed to find the people already attuned to my frequency, and let them know that they needed to “check this out”. It is the understanding of my smallest viable audience that has filtered into how and where I think about publishing my work. My job is to match my output with the kinds of people that are already looking to read what I’m writing about in the style and format that I typically write in.

You do not have a divine right to always be the consumer or spectator that someone had in mind when they were building or creating something. So why try and appeal to everyone with your product, your service or your content? There’s like eight billion people out there, more than five billion of whom are on the Internet. There’s probably a market for what you’re selling. You just have to find it. Whether you’re a writer of werewolf erotica, a seller of scissors for Bonsai plants, or an operator of a Youtube beauty channel for squid-ink-based make-up products - your task is to look for the individuals who would want ‘this type of thing’, and then give it to them.

Why go through the trouble of building an audience when you can find one instead?

So before you sit down to make something, before you dismiss something like a Pet Rock as silly, before you say it’ll never work - do yourself a favour and ask who it’s for.

Another storytelling masterpiece. Keep them coming. The tributaries will lead to the river.

"I’ve been writing online for three years, and it took me a long time to realise that I didn’t need the entire Internet to read my stuff. I just needed to find the people already attuned to my frequency, and say “Yo check this out.”"

Love this.