Substack Killed The Op-Ed Star

The passion economy, newsletters, and where publishing goes from here.

Every company is a media company (whether they know it or not).

The most valuable enterprise in ten years will be a media company.

The most valuable media company in ten years will be an individual.

Or a small group of people, but that doesn’t sound quite as prophetic. What is undeniable is that the window for disrupting the traditional media industry has never been wider. The gatekeepers of the old world have long since lost the keys to the kingdom.

The last decade has ushered in the Age of the Influencer, with a new class of Internet performers challenging us to redefine the rules of celebrity and clout. Quasi-media empires are being set up every day by Instagram models, podcasters, streamers, writers and even tweeters. You might not have noticed, because the new New York Times looks nothing like the old New York Times.

Each of these new stars has exploited a growing number of platforms and tools (the ‘Content Stack’) that have allowed them to turn their passions into their professions. They are living proof that in navigating the battlefield for attention, you’re better off employing the guile of an individual swordsman than the heft of a bulging army.

Substack, a relatively newer addition to this content toolbox, has a simple objective of giving any individual the ability to create, publish and monetise their own newsletter. It may sound like a humble raison d'être, but Substack is quietly attempting to own an essential building block of a modern media company.

By making it easy for anyone to start a subscription-based newsletter, they are providing a real alternative to the modus operandi of traditional publishers; ones who are suffering a full blown existential crisis due to the unravelling of advertisement-dependent business models that are as old as the internet. Substack’s endgame may well be in laying the groundwork to rebuild our crumbling Fourth Estate.

In this first edition of Tigerfeathers! I’m going to cover:

Part I (this week)

The origin of Substack and why its a cool idea

Part II, III and IV (over the coming weeks)

Why Substack is gaining steam in a time of ‘self immolation’ for traditional publishers

How it’s adding another pillar to the foundation of the Passion Economy

What the future of media looks like, and how Substack (and Twitter) fits into the equation

1] What’s a Substack?

The mission has always been crystal clear. Substack wants to ‘build a better future for readers and writers’.

Realising that today’s media environment is built on warped incentives that force journalists into a clickbait-fuelled race to the bottom, Substack founders Chris Best, Hamish McKenzie, and Jairaj Sethi sought to flip the attention economy on its head.

They created Substack as a way to change the game for writers so that they could be paid by their readers instead of advertisers. Built around the idea that a reader subscribes to a specific person, the goal was to place the relationship between reader and writer at the centre of a reimagined, sustainable publishing model.

“During the first 20-30 years of the internet, in terms of information distribution and media, the innovation has mostly come around an ad-supported model. There’s a whole 20-30 years of innovation to come that more fully innovates around a subscription model.” says co-founder Hamish Mckenzie.

So what is Substack actually offering?

Substack provides a platform that makes it easy for any writer to create an email newsletter, build a subscriber base, and commercialise their work.

Whether you’re a professional journalist looking for a better way to monetise your existing audience, or an amateur with a passion for writing about a niche subject, Substack will give you the tools you need to be a writer on the Internet.

On signing up you effectively get a Content Management System (CMS) that lets you post blogs to a website, send email newsletters, and integrate payments with Stripe. You get complete control over whether or not you want to attach a subscription fee to your work. You can decide if certain content is just for your website or if it’s only available to newsletter subscribers or only for paying subscribers.

Writers are empowered to do their best work. Readers can directly support the writers whose work they admire. Substack takes care of the rest.

Is this...new?

There are a number of platforms that exist today that allow you to write on the internet. But it’s fair to say that none of these have enshrined the reader-writer relationship at the centre of the equation quite like Substack.

Medium has been the de facto destination for publishing online for some time now. But they took the antiquated route of putting the Medium brand front and centre of what was happening on the website. This meant that authors weren’t able to independently communicate with or monetise their audience. Substack realised that the most important asset to a publisher is their audience, and Medium soon realised they had missed a trick.

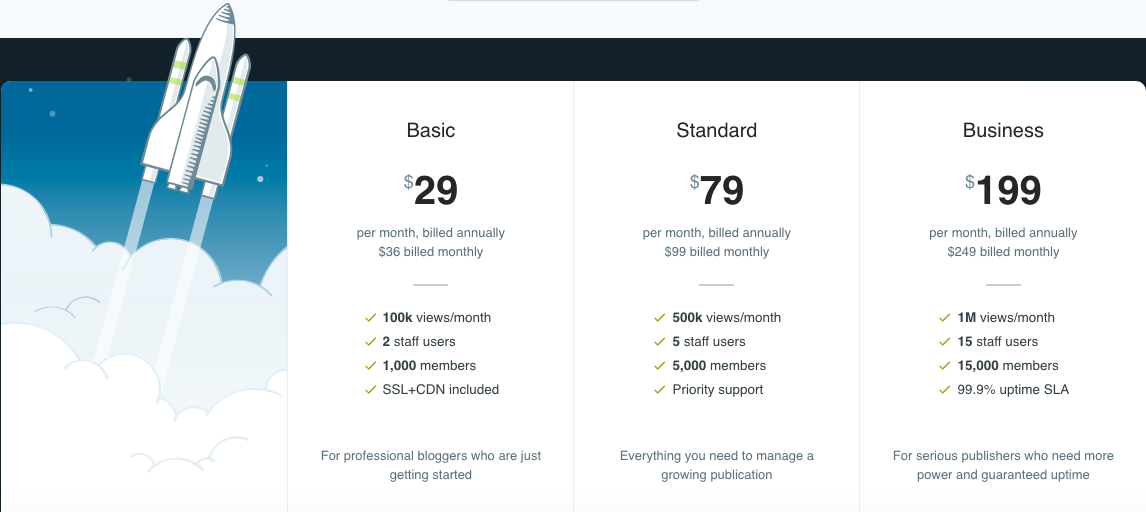

Substack also doubled down on simplicity. It is a much friendlier offering than other newsletter platforms like Ghost or Revue. These present a more professionalised service which could be intimidating (and expensive) for first time publishers.

There are other sites like Patreon, Campaignzee or Buy Me a Coffee that let you create an email list with subscribers in a roundabout way that is supplementary to their core offering. But Substack has made their value proposition easy enough for anybody to understand - make it simple for a writer to start an email newsletter that makes money from subscriptions. Boom.

Medium owns the relationship with the readers and the subscription revenue. They pay you each month based on an opaque and changing formula. They impose article limits and sign up requirements that ultimately hurt the writer. Substack is free to use, and the company only takes a 10% commission of the subscription fee from writers that choose to monetise their publications.

But will people pay for good writing?

Andreeson Horowitz seems to think so.

Substack claims to have millions of active readers on the platform and crucially over 100000 paying subscribers. They’ve already proven their concept in that many of their top writers are earning well into six figures like Bill Bishop who writes Sinocism (a weekly blog about China) or Judd Legum who writes a politics newsletter called Popular Information.

Liberated from editorial restrictions or the need to hunt for clicks, these writers have been able to earn their subscribers by consistently publishing quality content and becoming trusted voices in their respective domains. It is apparent that Substack works especially well for writers who have existing audiences and/or experience with newsletters. Bill had been publishing his free newsletter to over 30000 subscribers for five years, and Judd had experience as editor-in-chief of ThinkProgress and close to 300k Twitter followers.

The founders of Substack themselves admit that the platform is particularly effective when writers focus on a specific niche like InsureTech or Victorian literature, instead of trying to please the whole crowd. This model automatically incentivises writers to focus on quality, expertise and differentiation rather than the empty pursuit of eyeballs.

Danish research group AudienceProject found that only 13% of American consumers are paying for editorial content which means that Substack still has a massive behavioural shift to manoeuvre if it wants to function as a sustainable way for all writers to make a living. However you don’t need an outrageous number of paying subscribers today to be a successful writer.

Wired editor Kevin Kelly famously wrote in 2008 that you only need a ‘1000 true fans’ to make a living (but not necessarily a fortune) as a creator on the Internet, provided you can have a direct relationship with your customers. He argued that the Internet had allowed for the blossoming of infinite niches of different communities and topics which could be excavated for value. A single writer can build a critical mass of readers who are happy to reward them for work that is distinct, targeted and infused with personality (just like Ben Thompson and Scott Galloway have done with Stratechery and No Mercy/No Malice, respectively).

The reality today is that even in large media companies the reach of individual writers is, well, reachable.

Andrew Chen from a16z thinks that Substack is pioneering a new business model for culture. He thinks that the two-year old company ‘can solve the structural issues between publishers and readers in a way that aligns the incentives between all of them’.

In a media landscape that is increasingly seeing journalists as an expendable resource, writers now have the tools to walk down a different path.

Wait, I still don’t get it. It’s just an email newsletter, right? Who cares?

A newsletter is the surest bet a writer can make in a world that has condemned creators to the algorithmic lottery of social media slot machines. (The Pulitzer Prize committee offered to arrest me for that sentence).

Benedict Evans writes that ‘newsletters are a rediscovered form’, a spiritual successor to long form blogging that fizzled out in the early 2010s, in part due to the movement’s failure to monetize. Depending on who you ask, we are either at ‘peak newsletter’ or just at the ground level of the next-big-last-big-thing.

It is no surprise that traditional publishers like The Washington Post or The Times of London have begun using newsletters as a more reliable way to reach their readers. Even The Ken and The Morning Context, two young media publications that are leading the charge for subscription media in India, have begun to employ newsletters as a one-two punch with their regular content fare.

Whether just a set of curated links or a fully formed beast with its own editorial voice and style specifically suited to the medium, a newsletter done right harkens back to the days of print magazines where you received a piece of content that you could hold and keep. It is an intimate digital package promptly delivered to your inbox. The best ones can even feel like hearing from a friend.

That’s because email is the original social media feed. It is your home base. Your most sacred digital sanctum. It is what’s left after you strip away the decorative fluff of likes, followers and streaks from your online presence. Your email address anchors your virtual identity. And when it comes to consuming media, the people and content you let into your inbox will generally have to pass a higher bar for quality and interest.

"...we simply cannot trust the social networks, or any centralized commercial platform, with these cliques and crews most vital to our lives, these bands of fellow-travelers who are – who must be – the first to hear about all good things. Email is definitely not ideal, but it is: decentralized, reliable, and not going anywhere – and more and more, those feel like quasi-magical properties." says writer Craig Mod

If a tweet is like waving to someone on a busy street, a newsletter subscription is like an invitation into their home for a conversation. It is a personal, deliberate interaction in contrast to the ephemeral dance of a tweet on a timeline or a notification on a phone.

For a writer, ‘open’ social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter function as public squares. They are a good place to broadcast your ideas and announce what you’ve been upto. But they’re often too noisy to have a productive conversation and your message is often lost in the cacophony of other voices. A newsletter is a private conversation, at scale.

Mod continues to say that “...there's something about the framing of email - the inbox, that weird neither-here-nor-there networked space - that unlocks a permission to write about things I wouldn't otherwise feel...welcomed? to write about.”

A newsletter, and by extension Substack, provides a way for a writer to forge a connection with an audience that is interested in hearing their thoughts and opinions. Using email means you can go direct to consumer, without having to worry about being spotted on a news feed.

So I should quit my job and start a Substack?

Well, not yet.

Benedict Evans writes that “the new-and-interesting part to newsletters today is payment. Marc Andreessen is fond of saying that the web has an unused placeholder for payment (402), which is where Bitcoin is supposed to come in. But a paid newsletter uses very old tech: the change is the psychology, and the perception of value.”

Substack needs to prove that citizen journalism is worth paying for, and that there isn’t a finite audience for paying subscribers.

When the Times of London controversially chose to gamble on a subscription model over the traditional advertising route in 2009, they were told that ‘nobody would pay’ for general interest news. However, 10 years and 300000 paying subscribers later, they are now seen as trailblazers of sustainable journalism.

Times editor John Witherow said last year that “the paywall succeeded because we established a price for digital journalism. We recruited subscribers. We turned a profit. And we continued to invest in the highest quality journalism. This might seem obvious now but it is only with hindsight that we see that we were years ahead of our rivals.”

Substack’s greatest achievement will be in establishing a price for written content. Their north star is in reversing the decades of damage that ad-supported business models have inflicted on the publishing industry. It wants to help writers take advantage of an overall tilt towards subscription businesses (like Spotify did for the music industry) which could make writing commercially viable again.

Even though there is still some way to go before consumers line up to pay for content online, the founders promise never to integrate advertising into Substack because ‘media can’t be saved by an algorithm’.

Which begs the question, why does ‘media’ need to be saved in the first place?

If you (like my friends who helped edit this piece) are thinking “Bro did Substack pay you to write this?” The answer is, unfortunately, no. Although I’ve taken up the last 8 minutes of your time talking about Substack, this piece isn’t really about Substack.

This is about the time we live in, the battle for attention, and how traditional publishers have failed not just the people that work for them, but the people that rely on them to know what is and what isn’t true about the world.

Thanks for making it this far. Below is a sneak preview of Part II of this essay which will be published in the coming weeks. Make sure you subscribe to Tigerfeathers! so you don’t miss it.

2] How the Internet broke the news

“When a population becomes distracted by trivia, when cultural life is redefined as a perpetual round of entertainments, when serious public conversation becomes a form of baby-talk, when, in short, a people become an audience, and their public business a vaudeville act, then a nation finds itself at risk; culture-death is a clear possibility.” ― Neil Postman, Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. The Internet was supposed to unlock limitless scale for print media while obviating the industrial machinery required to produce and distribute physical newspapers. It was supposed to expand the reach of good journalism and supercharge the efforts of writers online. It was supposed to democratise access to information and be a stronger check against injustice and misuse of power.

However, maddeningly, the role of journalists in our tribe changed from truth seekers and truth tellers to ‘content gatherers sent to carve off slices of human attention to feed into a social media machine that seeks to addict rather than enlighten’.

To appreciate why Substack (and similar blogging tools) have captured the imagination of writers looking to go solo, you’ve got to first understand how we got here, and why the mainstream media finds itself in such a precarious position today.