Hey folks👋

Welcome to the 142 new Tigerfeathers subscribers who’ve joined the party since our last piece. If you’re still on the fence, you should know that we’re going to name our firstborns after the next 10 people to sign up👇

“If you were starting your career today, would you rather have a million dollars or a million followers?”

Ever since we started this newsletter in 2020 I’ve wanted to write about how the idea of a ‘traditional’ career path has been warped by the Internet, and particularly by social media. So this week’s piece is a little different than usual. Sure, it features themes that we’ve covered before - the future of media, the creator economy, monetising attention in the digital age - our usual fare. But its also the first piece where we’ve crowdsourced ideas and opinions from the Tigerfeathers community on Twitter to help breathe life into this essay.

I didn’t want to turn this into another 20000-word epic😅, so this is more of a thought experiment than a thesis, probably one I’ll revisit and revise as our adventure with Tigerfeathers rolls on.

Thank you to everyone who got involved (I hope I haven’t missed anyone out in the acknowledgements at the end of the piece).

One other update from behind the scenes: this week I kicked off a new weekly Twitter Spaces series on Web3 in collaboration with the fine folks at Business Insider🇮🇳 and Stocktwits🇮🇳.

I don’t know if I’d count it as the first official Tigerfeathers collab, but it fits in with my goal this year to (1) help onboard the next set of crypto enthusiasts in India (2) get the Tigerfeathers brand out on different platforms beyond the newsletter. Keep an eye out for Episode 2.

As always, feedback and comments are very much appreciated. With that, I’ll leave you to it.

You shouldn’t believe everything you read on the Internet. Especially not quotes written in cursive font against a black background next to prominent historical figures. Mahatma Gandhi isn’t responsible for the quote above. I made that image on Powerpoint. It took me less than two minutes to put together. Yes, it looks professionally done. I get it. I’m good with graphics and stuff. But you should know better. Sorry for the deception though, I’m just trying to make a point here. In all seriousness, the famous quote from the picture actually traces back its origins to a novel published by Anne Ritchie in 1885 titled Mrs. Dymond, where she writes:

“He certainly doesn’t practise his precepts, but I supposed the Patron meant that if you give a man a fish he is hungry again in an hour. If you teach him to catch a fish you do him a good turn.”

I imagine you’ll agree that Anne Ritchie deserves full credit for coming up with an adage that has retained its profundity even 137 years after the original publication of her novel. It has earned its place as an evergreen proverb in the shrubbery of the English language, forever touted as axiomatic proof that delayed gratification is a more reliable route to long-term fulfilment than temporary satisfaction. Misattributing her quote would be doing a disservice to her literary legacy.

I suppose the point I was (questionably) trying to make was that Mahatma Gandhi could have been responsible for coining such a poignant turn of phrase. Specifically this turn of phrase. In fact, you’d be hard pressed to find a historical figure who more emphatically beat the drum of self-reliance than the Father of the Indian Nation. The virtues of self-sufficiency and self-sustenance are forever embedded in the fabric of Swaraj, a philosophy he wholeheartedly endorsed, and one that would set the tone for India’s struggle for freedom from British rule. At its core, Swaraj was a movement that advocated for self-governance. It lionised individual autonomy, hailing it as the ultimate tool for collective empowerment, and the main catalyst for societal transformation.

“Growth will not be a pyramid with the apex sustained by the bottom. But it will be an oceanic circle whose centre will be the individual.”

Fast forward to 2022, and the lingering strands of this philosophy still percolate into our economic and social reform agenda - think Atmanirbhar Bharat, the National Curriculum Framework, Startup India, the NREGA Act - bipartisan programmes that were designed to equip Indian citizens with the tools they need to survive and succeed. Indian dreamers now dare to aspire to a higher standard of living akin to their Western counterparts even as we continue to chip away at the challenge of rural development. Indian entrepreneurs, on the other hand, have developed an audacious taste for world domination. They’ve demonstrated remarkable technical nous and (crucially) the ambition to apply these skills to conquer markets both home and away. Our country is more digitally and physically connected than it ever has been.

The digital age on the whole, however, presents a rather more intricate challenge when it comes to equipping individuals with the skills required for 21st century success. For starters it has splintered any sense of consensus around what constitutes ‘individual’ success. The Internet continues to stretch the canvas for human creativity, commerce and communication beyond our most fanciful projections. It has expanded and deepened the range of our lifestyle choices and economic pursuits. Social media lets us pick our own idols. We’re constantly evaluating and re-evaluating our models of ‘success’ in real time. This means that your quest for personal and professional fulfilment will probably look a lot different to someone else’s.

The milestones you plot for your life might never feature on someone else’s roadmap.

Cool, so what?

India boasts an envious demographic dividend because it houses the world’s second-youngest population. More than half of our population will come of age in the time of the Internet, smartphones and social media. We have an extraordinarily large contingent of individuals whose lives and ambitions will be significantly shaped by what they can do online. For instance, if you were starting your career today, you could reasonably hope to find a comparable level of success as a fashion blogger, a podcaster or professional gamer as you would as a dentist, a marketer or a consultant. That doesn’t mean you won’t have to work hard to get there, or that digitally native professions are any less legitimate than traditional jobs, or that your odds of succeeding are markedly different for each route. Your success will still come down to how effective you are at extracting the most leverage from your unique resources, capabilities and curiosities. But it also depends on how well you’ve been trained to excavate for opportunities on digital ground.

Assuming we’re all striving to reach some gooey utopia of security, stability and self-actualisation (“Huge if true”- Maslow), its useful to recognise that in the Internet age there are near infinite roads we can take to get from A to B. Each of these roads comes with a different set of directions. The Internet is effectively a prism that fractured our model of a ‘conventional’ life path into a kaleidoscope of viable options. Millennials and zoomers now have a generational window to redefine what constitutes a typical career trajectory (unlike the one playfully depicted in the animation below by digital artist Deekay Kwon that I’ve shamelessly tried to shoehorn into this piece).

On the Internet you are free to choose your own adventure. Each of these paths comes with its own trials and tribulations, requiring varying degrees of talent and temperament to navigate successfully. Anytime you’re interfacing with a smartphone or computer you’re teleporting into a shared digital circus where everyone in the world is competing against everyone else for your time, money or attention (and you’re invited to do the same). Packy McCormick, founder and editor of Not Boring, describes this as the ‘Great Online Game’, writing that:

“The Great Online Game is an infinite video game that plays out constantly across the internet. It uses many of the mechanics of a video game, but removes the boundaries. You’re no longer playing as an avatar in Fortnite or Roblox; you’re playing as yourself across Twitter, YouTube, Discords, work, projects, and investments. People who play the Great Online Game rack up points, skills, and attributes that they can apply across their digital and physical lives. Some people even start pseudonymous and parlay their faceless brilliance into jobs and money”

“We now live in a world in which, by typing things into your phone or your keyboard, or saying things into a microphone, or snapping pictures or videos, you can marshall resources, support, and opportunities”

“It’s less about a particular platform or outcome, and more about the idea that there are different ways of playing the game and new ways to acquire and grow new types of assets”

You can choose not to actively play, but its worth knowing that the game exists. To the untrained eye, the Internet (and social media in particular) can seem like a distraction from your goals - at best a source of entertainment, at worst a form of escapism. You may think it prudent to separate your online shenanigans from your ‘real’ world pursuits. However, to the seasoned craftsman the Internet is simply one tool in a larger toolbox to help you realise your ambitions. As more of our lives become intertwined with our keyboards and screens, most careers have evolved from linear tracks into circuitous highways with no defined start or end point.

These ‘3D’ career paths will define the future of work in the coming decade. If you’re plotting the next few years of your professional journey, its useful to understand that you have more options and more control over your voyage than you may realise. There’s a good chance you discover a unique path that no one else has taken before.

For instance, two decades ago if you wanted to be a college professor, you would at minimum need to have the requisite educational qualifications and theoretical foundation to teach the subject of your choosing. You’d likely have to begin with an administrative position at a university, or at an early K-12 classroom level stint, before building your way up to a tenured college gig over a number of years (or decades). Whereas today you can build an Internet ‘brand’ as a teacher by putting out thoughtful, entertaining videos on platforms like Youtube or Tiktok, demonstrating expertise on a particular topic and a flair for educating people on complex subjects. You’d be able to cash in on your talents by offering online courses on Teachable or creating tutorials on Masterclass, using the Internet to turn the whole world into your classroom. With the growth of online learning accelerating during the pandemic, going the digital route might play to your strengths more than abiding by the rules of the old system. Its not for everyone, but it might be something to someone.

Similarly, ten years ago if you wanted to work at a blue-chip venture capital firm, you’d need to start with having an MBA from a top-tier university. You’d need a few years of experience paying your dues (and losing sleep) either at an investment bank or a consultancy. You’d need to get your foot in the door as an intern, analyst or associate, before building up to your dream role as a General Partner with access to the best advisors, founders and startups to invest in. In contrast, today there are countless examples of individuals who’ve started their careers as investment professionals by tweeting, writing, podcasting or making memes about the products, sectors and technologies that they’re interested in. These individuals (like Packy McCormick, Harry Stebbings or Turner Novak) are able to build an audience and garner trust around their unique curiosities and opinions. They leverage their social capital to create investment vehicles from which they can deploy venture capital. They wield their celebrity (and content) as a differentiator to other commoditised VC funds. They become magnets to founders, familiar faces on their cap tables who can offer a spotlight to their stories and a credible distribution channel for hiring, sales and investment. Venture Capital has become an attractive (and ubiquitous) end game for content creators.

You can probably draw a similar parallel for pretty much any other professional pilgrimage in the digital age. The Internet has blurred the line between content and commerce. You can choose to play the money game, the fame game, the knowledge game or any other game, free to hop back and forth in order to find the route that gets you closest to the next level (whatever that may be for you).

For entertainers and athletes, podcasters or stand-up comedians, influence and investment are now freely tradable. We’ve seen record-breaking musicians start their careers as TikTokers. We’ve seen professional boxers start their career as Youtubers. We’ve seen celebrity teachers emerge from platforms like Udemy and Unacademy. Amateur chefs are turning their kitchens into home studios. We’ve seen musicians and models use their Instagram fame as a springboard for launching billion-dollar fashion empires. At the other end of the digital pool, entrepreneurs are turning the camera onto themselves, building independent media brands that function as dispensaries for business knowledge.

Fame is now an accessible commodity, which means the spoils of fame also come in many shapes and sizes.

Nice…what does this have to do with ‘self-reliance in the digital age’?

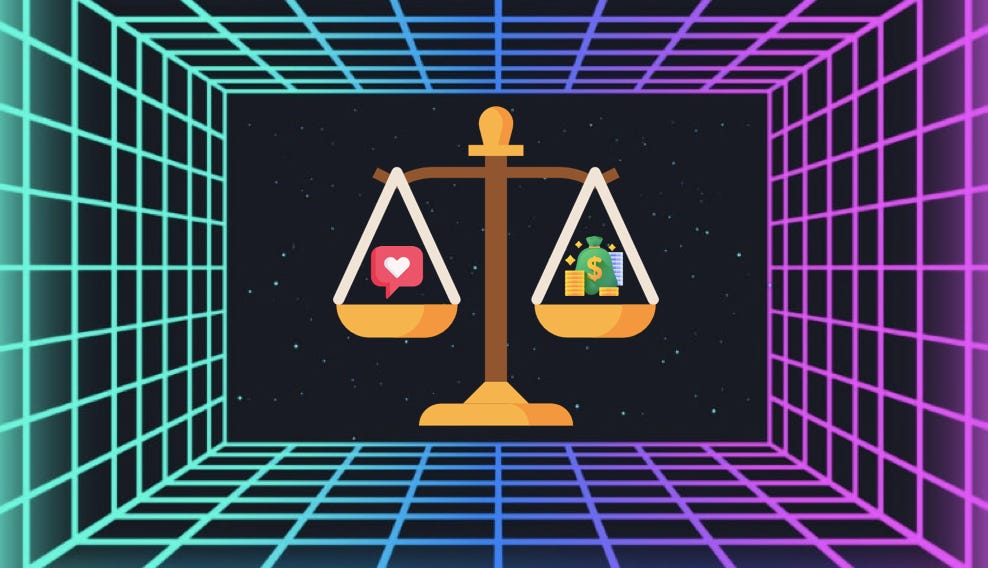

The central theatre of any 3D career path features a dance between audience-building and monetisation. You can choose to focus on one or the other, or (if you’re an especially graceful dancer) you try and balance both at the same time. You can either start a company, a business or a professional job, or you can figure out how to provide value for people over the Internet in a way that earns their attention. Monetisation comes later. You’re effectively choosing to earn in social metrics like followers, retweets, likes, badges, subscribers and comments that you can ideally trade in for ‘real world’ rewards down the road. Social media lubricates this exchange.

We do a large chunk of our internetting today on social media platforms. For most people, platforms like Twitter, Instagram, Youtube, TikTok and others are often the first port of call for the Web. Its where people spend most of their time and attention online. These platforms also function as global talent shows, representing the glitzy arenas of the Great Online Game. They are the ultimate beneficiaries of the contest for eyeballs between individuals and corporations. In the last decade and a half, much of the web has become Social, with gamified features presenting visible scoreboards for measuring your popularity on most websites and media pages. You can rack up ‘stars’ on Github for making valuable code contributions. You can get retweets on Twitter by writing great threads. And you can earn followers on Instagram if your debauchery look tasteful (jk). These metrics mean different things on different platforms, and certainly different things to different people.

The point is, that every ‘social’ platform equips you with a ‘social’ wallet when you sign up. That’s where you earn your ‘audience-points’ (vs dollars in your real wallet). In a time before the Internet, when ‘celebrity’ was a more scant commodity, the only way you could earn audience-points was if you found your way onto a big screen either as a professional athlete or entertainer (both of which are ultimately in the business of content creation). Nowadays everyone operates their own quasi-media company on the platform of their choosing. The scale of these individual media operations differs from person to person. Platforms that represent work for some people can function as recreation for others (and vice versa). The challenge is to figure out which ‘Social’ lever to pull that propels your 3D career forward. You may never have interest in directly monetising your content or output, but you can certainly leverage a loyal audience into future credentials, opportunities and collaborations.

I’ve been trying to work out the contours of my own 3D career. Six months ago I quit my job to focus full time on growing the Tigerfeathers brand, betting that this newsletter can become the first piece of a larger entrepreneurial jigsaw puzzle. For me the calculus is straightforward - can I eventually convert likes and subscribers into food and shelter? We may never succeed in monetising the newsletter, but I’m hoping at the very least that I can ride this thing to figure out what’s next. Tigerfeathers has already given me a chance to meet and connect with people I admire, and to collaborate on projects that have been personally and professionally rewarding. It still blows my mind that you guys take time out of your day to read our stuff.

It took me 8 years of bouncing around to realise that I want to build as much of my professional life around my writing as I can. If I was to give my younger self advice, it would be to start publishing my thoughts and ideas earlier, and to take Twitter seriously as a mechanism for serendipity. There’s an element of survivorship bias here of course. What works for me won’t work for everyone else. But I was curious about whether the notion of ‘audience building’ had seeped into the thinking of others in the context of their own 3D career models. I wanted to understand, if we’re all playing the Great Online Game, what people think is the most useful cheat code for their careers in 2022. I thought this was a mildly provocative way of finding out:

I thought the poll would help to check the temperature for how people think of audience building and monetisation in the context of their careers. The final tally was closer than I thought it would be. It was also consistent with anecdotal feedback from friends and colleagues to the same question.

I was curious what people would identify as the more reliable resource for long-term success. I wanted to know if you could make an apples-to-apples comparison for which of the two options represented ‘giving a man a fish’ vs ‘teaching a man to fish’. Which one sets a stronger foundation for a career in the Internet era? Is either one an objectively superior source of professional resilience?

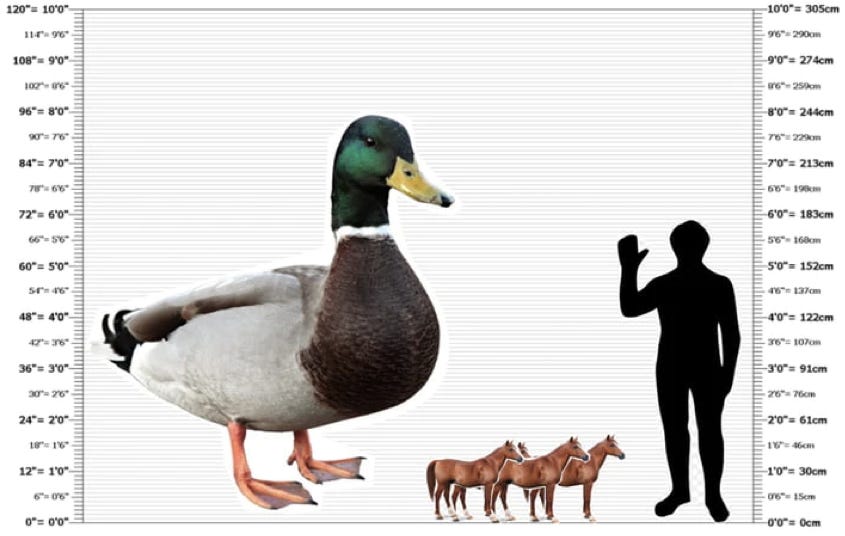

Like any classic hypothetical line of questioning (eg: “would you rather have the ability to teleport or the ability to fly?” “would you rather fight 1 horse-sized duck or a 100 duck-sized horses?” etc), the objective is not to arrive at a definitive answer.

Rather, its only to illuminate the colourful ways that people approach the problem statement. You’d be surprised at how the application of different constraints and vantage points can radically alter the playing field, exposing you to mental models you might have never considered when thinking about your own life and career.

Break it down?

For starters, it depends on what status game you’re playing. Eugene Wei famously recounted that two of the most indisputable truths about human nature were that “People are status-seeking monkeys” and “People seek out the most efficient path to maximizing social capital”. His thesis was that social media platforms have given us a way to quantify social capital in the same way that money gives us a way to measure financial capital. There are, of course, countless other mini-games you can choose to play - ‘the making-a-difference-to-the-world-game’, ‘the mastering-your-craft-game’, ‘the doing-what-you-love-game, ‘the giving-back-to-society-game’ etc. But fundamentally your choice of status game will inform the type of rewards you optimise for in each stage of your career. Perhaps more importantly, it will inform the types of rewards you don’t optimise for.

A professional investor cares more about her investment track record whereas a musician is more concerned with how many people streamed his album on Spotify. The investor doesn’t care about the engagement on her last Instagram post, and an artist isn’t measuring his professional worth based on the returns of his stock portfolio. From Nick Magiulli’s excellent piece on the subject:

“…whatever status game you choose in life ultimately determines what you optimize for. Choose money and you’ll end up working all the time. Choose beauty and you’ll always want to look better. Choose fame and you’ll constantly be seeking attention.

Each of these choices has consequences too. Your pursuit of wealth could leave your personal relationships in shambles. Your pursuit of beauty could impact your mental and physical health. Your pursuit of fame could end up ruining your reputation.

Whatever status game you decide to play, you have to ask yourself: are the benefits worth the costs?”

Are the trappings of fame more pernicious than the trappings of wealth? Is reputation more vulnerable to collapse than net worth? The great Bill Murray once said that “I always want to say to people who want to be rich and famous: try being rich first. See if that doesn't cover most of it. There's not much downside to being rich, other than paying taxes and having your relatives ask you for money. But when you become famous, you end up with a 24-hour job.” We can all recall plenty of examples of high profile figures whose stars have faded after their moment in the spotlight subsides. Or when they say something politically incorrect on social media. Or especially when they

Hollywood shenanigans aside, the truth is, a little fame (and particularly a little Internet fame) can be a useful resource if nurtured the right way, especially in the context of niche Internet communities that assemble around specific interests and topics. Internet fame allows you to become a lighthouse for like-minded people.

Aviral Bhatnagar, an investor at Venture Highway, was only in his second year as a student at IIT Bombay when he discovered a mini-blogging platform named Quora that functions as a ‘personalised google search’. He began answering questions from Indian students regarding IIT life and the IIT application process. His consistency and honesty helped him amass a loyal audience of ambitious Indian youngsters that wanted to crack the IITs. Aviral eventually expanded his scope and began writing about the Indian tech ecosystem, which culminated in him moving off Quora to set up an independent newsletter called ‘A Junior VC’ (AJVC) that documented his learnings about Indian venture capital and startups from his perspective as a young VC. AJVC today has grown into arguably the premier side-hustle for young professionals in India that are curious about our startup ecosystem. It is now a trusted a media brand for Indian tech that also provides deal flow to Aviral’s day job as an investor, and gives him tremendous leverage when navigating his own career.

Returning to our poll, a frequent point of contention from responders was around which asset was more ‘stable’ and which one was more scarce. I’d argue that in a world of infinite content and 24 hours, attention is the most precious asset. But it is also a more ephemeral resource for the same reason. With infinite options for information and entertainment, people are entitled to be promiscuous with whom they decide to share their time with. As one of our readers pointed out “I’d rather have the money. Followers can be fake, the money not. I’d use the money to invest in people, that will lead to having more fruitful connections”. Having to placate an audience might not give you as much peace of mind as money in the bank. You’d need to weigh your choice of ammunition against your starting position in the game. Then its on you.

Where do you thinking you could exploit the magic of compounding? Are you a master capital allocator, can you turn that $1 million into $10 million? Or do you think your million-strong loyal audience is more likely to tell all their friends about how great you are? Are you more of a Warren Buffett or a Tim Ferris?

Which one gives you more shots on goal? Having a loyal audience and built-in distribution absolves you of the need to budget for marketing expenses. Your customer acquisition cost for any venture is essentially zero. Lets say you were starting a restaurant. Do you think its chances of success would be higher if you spent $1 million to set up and promote it? Or if, like Youtuber Mr.Beast, you could tap into a rabid following of 95 million subscribers who are happy to support your ventures (like Mr.Beast Burger) because you’ve put so much effort into entertaining them over the years. Your audience might be more forgiving of failure, but a bad investment is a sunk cost you’re likely never getting back.

The broader conundrum here is around how to assess the monetary value of a fan following. Its easy to calculate your Return on Capital or Return on Investment. But how do you predict a Return on Audience? How much is a follower actually worth? How many do you need to make it worth your while?

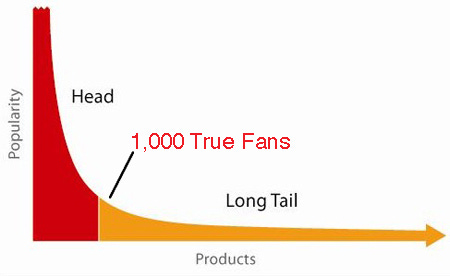

Wired magazine editor Kevin Kelly famously wrote in 2008 that you only need 1000 True Fans who ‘buy everything you produce’ in order to be a successful creator online (provided you could directly earn $100 on average from each true fan). You don’t need to boil the ocean. You just need to identify one of the millions of niche communities on the Internet that appreciates your contributions or values your opinion.

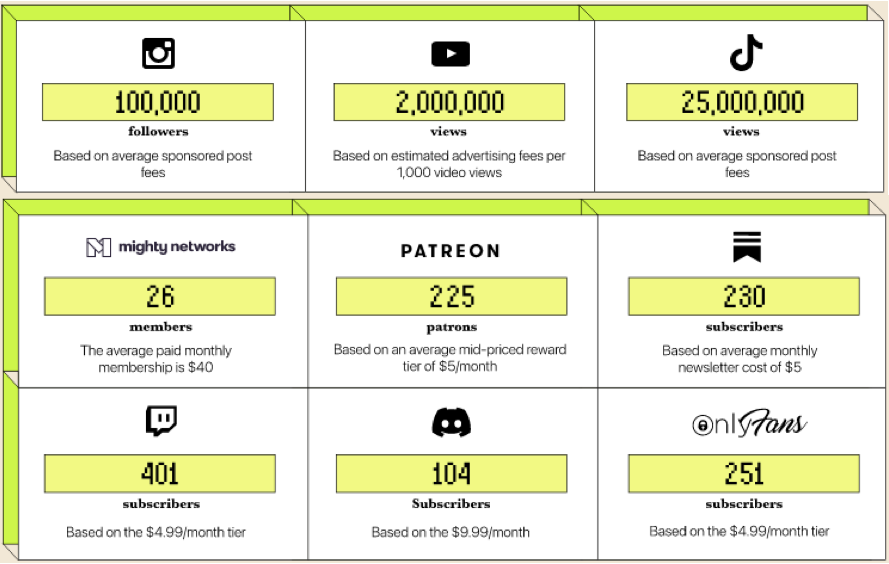

More recently, the legends at Nonfiction Research & Bodacious Studios actually did the math to find out how many followers you need in order to make $1000 per month.

Their study takes into account your ‘True Fans’, the ones who “will drive 200 miles to see you sing; they will buy the hardback and paperback and audible versions of your book; they will purchase your next figurine sight unseen; they will pay for the ‘best-of’ DVD version of your free youtube channel; they will come to your chef’s table once a month”. The rise of creator platforms (Patreon, Shopify, OnlyFans etc) and influencer marketing mean that ‘audience’ is more directly monetisable than ever before through mechanisms like advertising, tipping, subscription fees, or even NFTs. You can build a brand around promoting someone else’s products, creating and selling your own products, or leveraging your distribution in exchange for the opportunity to invest in promising startups. These creators that operate independent media brands engaged in some combination of content and commerce will come to represent the atomic units of the Web - AKA the small businesses of the Internet economy.

"I'm not a businessman, I'm a business, man" - Jay-Z

Think of Dwayne Johnson as the ultimate example of someone who successfully alchemised wealth from audience by bridging the online and offline worlds. He began his career with crushing failure, falling short of his dream of being a professional NFL player, before going on to become a cultural icon in the WWE as ‘The Rock’. He leveraged his fame into a successful movie career while simultaneously amassing a huge Instagram following on the back of his natural charm and charisma. With 278 million followers in his corner, he’s now parlayed his social capital into building a tequila brand, an energy drink, and an apparel line - all while staying true to the values that are important to him.

Although the metrics above are a useful guide, they belie an unfortunate truth about Internet fame. Most creators and Internet celebrities never directly monetise their audiences. Rather, they siphon their audiences into offline credentials and opportunities. For instance, if your hobby is to create reviews of popular cosmetic products on TikTok, you could probably leverage that experience into a full time job with a major make-up brand. Your audience might be small, but your TikTok page says much more about you than a line on a CV ever could. Its the same for creators on other mediums too. 14-year old Goan teenager Gajesh Naik started to make a name for himself during the pandemic (when he was only 12 years old) by publishing tutorials on computer programming on Youtube specifically aimed at kids his age. Two years later he’s now the chief architect of PolyGaj, a decentralised application built on the Polygon blockchain that manages more than $1 million in crypto assets.

Examples like his validate the thesis behind 3D careers. It also exemplifies how Gen Z intuitively understands how to play the game. But you don’t have to be Kylie Jenner to see the benefits of bending the Internet to your will. If your recent LinkedIn post helped draw the attention of a talented candidate, congratulations, you already understand the power you have to shape your digital destiny. The point is that each of these social platforms can be mined for offline career success. You might think that your profession or your sector is immune from Internet intervention, and that you have no use for building an audience. But it might be worth taking a second look (this time with 3D glasses on).

*sigh* Okay, tell me how to get started.

First things first, lets get this out of the way - none of this is universal advice. Not everyone has the freedom or the privilege to cherrypick their own path. Not everyone wants to complicate their trajectory. If you’ve already found your calling and you’ve figured out how to get there - amazing, you should probably keep going. But if you find yourself stranded on a professional ladder somewhere trying to plot your next move, maybe you need to hop onto a different ladder? Maybe that ladder doesn’t even look like a ladder. Maybe it looks like a rock-climbing wall? Or an escalator? Or a game of Super Mario?

A good starting point for a 3D career is to pinpoint exactly where the Internet has infiltrated your chosen profession. Bonus points if there isn’t an obvious answer yet. Entrepreneurs have spent the last decade looking at this problem statement from the prism of technology (“Software is eating the world”). But social networks have invited individuals to approach this challenge with a media-oriented mindset too. In other words, you don’t have to just resort to starting a company to impact the world. There’s plenty of ways to make a difference to people’s lives that also let you tap into your own quirks, interests and hobbies, outside of traditional entrepreneurship.

For instance, Miekii (Michael) is a bike messenger based in New York City who delivers food across Manhattan for UberEats. He also happens to have over 50K followers on Twitch who tune in everyday as he livestreams himself zipping through the streets of New York on his bike route while pointing out his appreciation for different parts of the city. Not only has he added another dimension to his day job (literally), but his Twitch channel allows him to monetise his love of exploring, and double-down on the joy he gets from bringing people along for the ride.

One of my favourite newsletters is Patent Drop. It was started by Neer Sharma while he was figuring out his next move after previously co-founding a social networking startup called HaikuJAM. Every week Patent Drop gives you ‘a summary of 3 new patents from big tech companies and a wider list of all patents from these companies’. Why? Because ‘patents are a great way of getting a peek into the future before it’s been built and released’. You can instantly see why this would be compelling content for readers working in tech, finance or business. Patent Drop gave Neer a way to build an audience (of over 200K subscribers) while he nerded out on stuff that he would have spent time researching for himself in any case. In the bargain he turned a side-hustle into a media instrument that he can use to wedge open a number of professional doors that may have otherwise been closed to him.

The lifeblood of social networks is user generated content. Anyone that posts anything on social media is technically a content creator. And as creators continue to discover imaginative ways of using the Internet to amplify their voices, international grade content will become as lucrative as international grade software. The Total Addressable Market for differentiated content now includes anyone with an Internet connection.

For example, Khaby Lame is a Senegalese-born social media star based in Chivasso, Italy. After losing his factory job at the start of the pandemic in March 2020, he began spending time on TikTok, and quickly gained global notoriety on the back of his viral reaction videos to complicated life hacks for everyday solutions. He is currently the second-most popular TikToker with 137 million followers and has leveraged his Internet fame to strike endorsement deals with brands across the world like Hugo Boss, Xbox, Netflix, Amazon Prime, Juventus, and even India’s Dream 11.

Its worth mentioning that not all professional pursuits lend themselves to productive voyeurism (i.e. you don’t want your heart surgeon to be worrying about making TikToks in the operating theatre). The point is to figure out what makes you unique, and which parts of your experience, your personality, or your knowledge would resonate most with someone else. How can you add value to an Internet stranger’s life? How can you manufacture a professional advantage from your unique mix of passions and skills?

Kat Norton (better known as Miss Excel) has amassed over a million followers between Instagram and TikTok by creating helpful (and entertaining) videos on…Microsoft Excel😁. Her social media content functions as a hook for her real business of running Excel training courses, where she earns six-figures in revenue every day.

Palak Zatakia had just dropped out of college in India when one of his former batchmates reached out to him for advice on how to build a reading habit. Realising that simply offering a book recommendation would be a futile (and lazy) effort, he instead began sending his friend one (interesting) article to read over Whatsapp everyday, and following up to make sure he actually read it. Not only did it work, but word spread fast, and Palak turned this humble offering into a daily Whatsapp newsletter that peaked at 72k subscribers. He regularly fielded inbound requests from brands that were looking for an authentic and targeted way to reach a young, curious audience. He even managed to spin out this habit into a ‘micro newsletter’ platform called Sublist. The experience gave him the confidence to plot his next venture.

Hikaru Nakamura was just an ‘average’ chess grandmaster when he discovered steaming platform Twitch in 2018. Although Twitch was mainly known for its video game streamers, Nakamura carved out a niche for himself as one of the best content creators on the platform, streaming everything from friendly games with other grandmasters, walk-through tutorials of his strategies, and sometimes even games that he played blindfolded. He catalysed the booming popularity of online chess through the pandemic, in turn elevating his own profile to the point where he became the first chess player to sign with professional eports organisation Team SoloMid for a six-figure sum in August 2020. His digital flywheel now includes a popular Youtube page and a private Discord server called ‘Naka's PogUniversity’ where he gets to talk shop with other chess enthusiasts from around the world.

Why should people pay attention to what you’re doing? What can you offer to people that they can’t get anywhere else? How can you take advantage of a global audience? What medium do you excel at (no pun intended)? Remember its not about forcing the issue. By all means, play around. Experiment. Do what comes naturally to you. Refine and repeat. And when you find something that sticks, when you discover that elusive bit of Internet magic - then you think of doubling down.

When we started Tigerfeathers in the summer of 2020, it was just a fun way for us to assault the public with our opinions on startups, crypto, fintech - stuff that we thought was interesting. I had just left my job at the start of the pandemic and had no clue what I was going to do next. But I knew that I enjoyed writing. The rise of creator platforms like Substack, Ghost and Revue had been a trending theme in the wider cultural zeitgeist, and it seemed like newsletters were cool again. So we picked a silly name and started publishing long-form content that was largely focused on India’s tech ecosystem. It was a Tigerfeathers essay that landed me my next gig at Visa at the end of the year. By the time I had settled in, we had crossed 1000 subscribers. The problem was that I now had a side-hustle that was more personally and professionally rewarding than anything I was doing in my ‘real’ job. I used to feel guilty about wasting time reading blogposts, messing around on Twitter and thinking about my next piece. But I now chalk that down to a failure of imagination.

Our definition of work is too narrow for the Internet age. Creating any type of digital content or investing time on social networks that let you make new friends and connections is not wasting time, especially if it leads to interesting projects and collaborations (monetary or otherwise). Lurking around in communities on Discord and Reddit can inspire your next great idea. DM-ing your favourite podcaster, publishing a tutorial on Youtube, sharing your thoughts in public - it all counts. Work and play can often look the same. Worst case, you meet some interesting people and learn something new. Best case you figure out what you really want to do.

“The same “rugged individualism” described in the Roaring Twenties 1.0 will drive dinner party discussions in the Roaring Twenties 2.0 where individuals will discuss their podcast, newsletter, creative endeavors and angel investments while quietly working normal jobs.”

- Brianne Kimmel (Welcome to the Roaring 20s)

Its possible that this entire essay is just an exercise in reflexive justification. But its also possible that there’s a better way to look at all this career stuff. The Internet has forever changed the way we live, work and play. Its probably time we applied a digital lens to our careers too, reworking the model for how we *should* allocate our time and effort. Its not about thinking outside the box (or inside the box for that matter).

It starts with just noticing the box.

Closing Thoughts

“Make yourself useful to smart, successful people. That’s how you should spend the first ten years of your career.

Surround yourself with smart, successful people and then bet on them. That’s how you should spend the next ten years. And then you’re done, if you want to be done.”

I started my career back in 2014 with a four-year stint as a management consultant at KPMG in London. In my last week at work before moving back to Mumbai, I had the chance to chat with a senior partner who was calling time on four decades at the firm to spend his retirement sipping piña coladas on a beach in Mallorca. I remember asking him an unimaginative question about the most important thing he’d learned over the course of his career. He told me that he’d spent 39 of his 40 years working out of KPMG’s home base in London, with the lone remaining year spent on secondment to our Canadian office. Curiously, he admitted that the year he spent in Canada was the most important year of his life because “once you learn there’s one other way to do something, you realise there’s probably a hundred other ways to do the same thing”.

This seemingly innocuous nugget of wisdom has stayed with me over the years. It kind of inspired this piece as well. The whole point of highlighting a different mindset for career building is just to illuminate all the different paths to achieving your (/my) goals. There are more ways to do this career thing than you realise. It may not be apparent yet, but the consequences of living in a smartphone-equipped world are percolating through the professional value chain. It provokes society-at-large to ponder some exotic readjustments, like questioning whether:

Audience-building would be a more useful skill to teach kids today than geometry? (I’m mostly joking, relax)

Or should media training be part of every core curriculum? What about capital allocation?

Does career counselling need to begin with an intro to shitposting?

Should ‘creator’ case studies be as important as corporate case studies?

Should people build careers in the same way that entrepreneurs build companies? i.e. an entire generation of tech entrepreneurs has been trained to focus on acquiring users as fast as they can, and worry about monetisation later. Could we have ‘audience-first’ careers in the same way we have ‘user-first’ products? Would capital allocators consider investing in people in the same way they do companies?

Instead of disqualifying candidates for their social media indiscretions, should companies reward talent who’ve demonstrated a knack for building an audience? Wouldn’t their brand-building and marketing activities be bolstered by having in-house influencers who natively understand how to draw eyeballs online?

Social media in particular has allowed you to play the career game on two levels. It turned us all into warlords at the helm of our own little media fiefdoms. We’re all celebrities in our little corners of the Internet (sometimes just to our friends and families, sometimes to our colleagues, and sometimes to the world). You probably have more digital influence than you realise.

“Influence is no longer about being an elusive star on the red carpet; influence is about being intimately familiar and relatable” - Rex Woodbury

Unsurprisingly, there’s still a certain section of people who use the term ‘influencer’ as a pejorative. Thats mostly because they’re looking at it backwards (and also because some ‘influencers’ don’t really help their case). Influence is a function of value creation. Individuals who excel at entertaining people, making them laugh or helping them learn new things attain influence as a by-product of earning trust from a loyal audience. That’s fair game. The influence they generate can be wielded for further value creation (selling a product, endorsing a brand, finding a job, investing in a company etc). People that aim to be influencers by mimicking their idols are really trying to reverse engineer the process, and will generally end up without the result they’re looking for. They also end up tainting the overall perception of content creation as a respectable pursuit by attempting to cheat the game.

The aim of this piece is not to make the claim that everyone should be an influencer. Or that every career should be accompanied by a ‘social’ component. Or that if you’re not simultaneously drafting thoughtful tweets in your lunch break everyday then you’re somehow being left behind your peers. No, that would be silly, and would add fuel to the fire of hustleporn that is already responsible for more toxic fumes than any professional workplace should have to contain. My objective is just to point out that people are different, and the Internet has given us the freedom to plot our careers in a way that maximises our individual strengths and passions. Its less about stepping outside your comfort zone and more about finding your comfort zone.

“Find out who you are and do it on purpose” - Dolly Parton

Some people can do more with Instagram than they can do with Excel. Some people enjoy memes more than they enjoy meetings. Some people would rather independently contribute code to a number of projects working from coffee shops around the world than be tied down to a single office or employer. If we want to empower the next generation of Indian dreamers who seek to make an impact on the world, its important they recognise there’s more than one way to do it.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to everyone who filled out the poll on Twitter and to Abhishek Murarka for helping to spread the word. I’m grateful for all the folks who were generous enough to share their own thoughts and experiences including Monica Jasuja, Sachin Gupta, Nathan, Yahya Ahmed, Ashwin Doke, Lakshmi, SR, Moti B, Surbhit Agrrawal, Manveer, Bhavesh Nayak, Parvaz Cazi, Ambuj Junjhunwala, Numbers & Narrative, and all my friends I’ve harassed for their responses. Thank you to Aaryaman Vir, Neer Sharma, Akshay Mehra, Palak Zatakia and Sajith Pai for helping me refine this piece.

Are you in the midst of a 3D career? If so, what does yours look like? If not, could you find a 3D path if you wanted to? What did I get wrong? Is there anything I should have considered?

Part 2 of this piece is is going to be based on feedback from the Tigerfeathers community. Let me know what you think either in the comments or on Twitter. As always, thank you for taking the time to read🙏

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rahul Sanghi most recently served as Fintech Lead for Visa in India & South Asia. He began his career as a consultant with KPMG in London, spending a majority of his time helping the firm set up its global enterprise blockchain and crypto asset advisory practice. He moved back to India in 2018 and joined Koinex (then India’s largest cryptocurrency exchange) as Director of Business and Strategy, before assuming the same role at B2B-SaaS startup FloBiz. He is currently the co-founder of Tigerfeathers, a media brand that is being built for Web3. He doesn’t know why he’s writing this in third person, but whatever.

This man truly has a knack for writing. ♥ for this substack. Keep writing.

tbh one who had read the great online game and missed this piece , missed nothing

tl;dr : once you learn there’s one other way to do something, you realize there’s probably a hundred other ways to do the same thing