Hey everyone👋

Welcome to the 506 new Tigerfeathers subscribers who’ve joined since our last piece. Whether you’ve been with us for one week or one year, we’re grateful to have you on board.

If you haven’t joined the party yet, here’s your chance. All new subscribers get free tickets to ‘Tigerfeathers: The Musical’ later this year. Trust me, you don’t want to miss it.

Last time out I mentioned that Tigerfeathers was going to be my full-time gig for the foreseeable future. A number of you reached out to ask what the hell that means for you and what that means for us. Both valid questions.

For starters, it means that we’re going to try and find a consistent publishing cadence for this newsletter. If you’ve been with us since the early days, you know that we’ve made some really dumb commitments about how often we’re going to write - once in two weeks (lol), once a week (LOL) etc etc. I’m not going to do that this time. What I will say is that the north star this year is growing the Tigerfeathers brand, so I’m trying to balance content creation with other interesting advisory and investing work that helps keep this show on the road. I’ll probably experiment with shorter pieces too (you’re welcome) that allow me to publish more often. It won’t happen overnight, and will likely take some process fine-tuning, but thats something I hope to figure out over the course of this year.

More importantly, a number of you wanted to know if ‘going full time’ meant that this was going to become a paid newsletter. Don’t worry, that’s not part of the plan. We want to throw the best party on the Internet where everyone’s welcome. It’d be silly to add velvet ropes outside the nightclub already. Tigerfeathers exists today because you guys have been in our corner since the start - reading, commenting and sharing our work (pls keep doing this<3). Wherever this ship is headed, we don’t want to leave any of our crew behind. On the contrary, we’re hoping to running some fun experiments with our community this year. Stay tuned.

Anyway, back to our regular scheduled programming. One of the biggest technological themes to emerge in 2021 was the arrival of ‘Web3’ into regular socio-cultural parlance. Web3 is the corporate-approved umbrella term for the zany world of blockchain technology and crypto assets. It is a reimagining of the Internet where users and builders have a greater ownership over their digital identities and data, along with a greater say in the governance of the platforms we use on a day to day basis.

My co-founder and I have been involved with this space in a number of different capacities for several years now. We’ve written extensively about crypto in our essays on Bitcoin, Polygon, Mudrex, Web3 and the Metaverse. A big goal for us this year is to demystify the complexities of Web3 for our readers. This stuff can feel intimidating, inaccessible and irrational if you’re a newcomer, so we’re hoping that Tigerfeathers can be the intellectual starting point for readers that want to dive head-first into the crypto rabbit hole…which brings us to today’s essay. I won’t say too much, but it covers the evolution of human storytelling - from myths to memes to NFTs. NFTs have captured the majority of my attention in the last 12 months, and I wanted to write a piece that went below the surface and beyond the hype to explain why this technology is such a big deal, and what’s really going on here.

As usual (sorry) its not a short piece. But if you do make it to the end, and you think this was a good use of your time, it would mean a lot to me if you took a couple of seconds to share this post. And with that, I’ll leave you to it.

“What unites people?”

“Armies? Gold? Flags?”

“Stories.”

“There's nothing in the world more powerful than a good story.”

“Nothing can stop it. No enemy can defeat it.”

“And who has a better story than Bran the Broken? The boy who fell from a high tower and lived…He's our memory. The keeper of all our stories. The wars, weddings, births, massacres, famines, our triumphs, our defeats, our past. Who better to lead us into the future?”

- Tyrion Lannister (Westeros, 305 AC)

When’s the last time you paid attention to the news? I mean really paid attention? Not to the content itself, but to the nuances of the presentation. I wouldn’t blame you for wanting to spare yourself from the manufactured hysteria that passes for objective truth these days. But if you look past the noise, you’ll find many of humanity’s secrets buried in the production that conjures up everyday broadcast programming.

Pay attention, and you might notice the deftness with which characters are assigned to precise positions on an editorial chessboard - the good guys, the bad guys, the heroes and villains, the winners and losers, the right side and the wrong side.

Expose yourself long enough, and you start to see familiar templates applied in the act of deconstructing reality for daily consumption. You will find that there are only a finite number of ways to dress up a series of events into a compelling synopsis. These are the recurrent accounts of unpredictable markets and stirring political victories, of underdog entrepreneurs and corporate skullduggery, of agonising sporting defeats and scandalous celebrity gossip, of unwilling messiahs and unfortunate scapegoats, of warring tribes and crumbling empires, of heartbreaks and 15-minutes-of-fame. We know these tales well. They are as old as time. The news may be new, but the narratives remain the same.

These days, the press isn’t too concerned about disguising its intentions. The primary function of the news media today is not so much to educate and enlighten but more so to dazzle and delight. You see it most in the melting of delineations between conventional broadcast segments - Business, Politics, Sports and Entertainment have all become different flavours of the same thing.

Politics has been reduced to a festival of elections and a perpetual tournament of races. The noxious scent of money in power has swayed all manner of opportunists to follow the lucrative path of national and international governance. The most riveting battles in modern society don’t take place in stadiums or stages or open fields, but at the ballot box.

The purity of sport, in turn, has been sullied by the chicanery of men in suits, who turn to the arenas of football, cricket and athletics to expand their commercial empires and wage their political contests. The drama of high-level competition, marketed superbly by professional leagues and broadcast partners, has spawned juggernaut entertainment brands around these players and teams. Global fanbases today demonstrate a quasi-religious fervour over their favourite sporting icons, giving the most popular teams and players a revered position at the vanguard of pop culture.

This is catalysed by the fact that we live in a time of microwave fame. The cult of celebrity has permeated every crevice of modern culture. No one is immune from being starstruck, and the Internet has made it easier than ever for new stars to be born. Modi or Musk, Messi or Malala, we all have our idols. Their journeys - their victories, their defeats, their campaigns, their fears - become our own. With an infinite number of distractions to choose from, we gravitate towards the most captivating forms of media and the most compelling characters, meaning that there is a premium to be enjoyed by those who can command our attention.

That’s why entertainment is big business. And big business has always been entertaining. The mythology that surrounds popular CEOs, the coronation that greets a successful funding round, the productive medley of concept and capital, the bloodlust that follows the biggest corporate rivalries - all make for worthy spectacle.

You see? The cast and setting might change, but everyone’s reading from the same script. You can try changing the channel, but all you will find is different episodes of the same show. Lets say you enjoy the guilty pleasure of watching the Kardashians navigate their sex lives. Or maybe you prefer the manufactured drama of the Premier League or WWE. You might even find the political theatre of Washington or New Delhi more to your taste. Or you could be the type of person thats only concerned with the latest technological breakthroughs and what they mean for mankind. We tell ourselves that we’re unique. We want to believe that the things that capture our attention are what make us different. We define ourselves by what we are not. But at the end of the day we’re all susceptible to the hypnosis of a compelling narrative, irrespective of the actual setting or subject or people involved. The news business then, is not the ‘news’ business but the ‘stories’ business. And we are addicts, perpetually on the lookout for our next narrative fix.

Like moths to a flame, we gravitate towards the best stories we can find.

Homo Fictus

“Why do stories cluster around a few big themes, and why do they hew so closely to problem structure? Why are stories this way instead of all the other ways they could be? I think that problem structure reveals a major function of storytelling. It suggests that the human mind was shaped for story, so that it could be shaped by story.”

- Jonathan Gottschall (The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human)

In ‘Sapiens’, his seminal book on the origin of our species, Yuval Noah Harari elucidated one of the core tents of the human experience - storytelling. Key to our ascendance as the dominant species on earth was our ability to tell stories about things like recent events (“Greg just got eaten by a lion”) and interpersonal gossip (“Anand has been kind of a dick to everyone in the tribe lately, maybe we should drop a boulder on him?”). These stories allowed us to build reciprocal relationships amongst the members of our immediate social group and helped us to make plans and take actions that would benefit the tribe.

However, the linguistic catalyst that allowed humans to coordinate and cooperate in large groups that spanned cities, countries and continents the world over was our ability to create and sustain collective fiction. In other words, the greatest differentiator between humans and other animals was our unique capacity to tell stories about things that didn’t exist.

“How did Homo sapiens manage to cross this critical threshold, eventually founding cities comprising tens of thousands of inhabitants and empires ruling hundreds of millions? The secret was probably the appearance of fiction. Large numbers of strangers can cooperate successfully by believing in common myths. Any large-scale human cooperation – whether a modern state, a medieval church, an ancient city or an archaic tribe – is rooted in common myths that exist only in people’s collective imagination.

As far as we know, only Sapiens can talk about entire kinds of entities that they have never seen, touched, or smelled.

Legends, myths, gods, and religions appeared for the first time with the Cognitive Revolution. Many animals and human species could previously say, ‘Careful! A lion! Thanks to the Cognitive Revolution, Homo sapiens acquired the ability to say, ‘The lion is the guardian spirit of our tribe.’ This ability to speak about fictions is the most unique feature of Sapiens language.”

- Yuval Noah Harari (Sapiens)

Our brains evolved so we could utilise our superior linguistic capabilities to weave enthralling tales about the nature of our reality, so we could identify patterns and construct logical threads that allowed us to make sense of our surroundings. The ability to squeeze narrative from the pulp of information is a gift uniquely endowed to the human mind. It is hardwired in our DNA. It has allowed us to tame and master our natural environments. Most of all, the proclivity for storytelling has allowed us to create a multitude of social innovations that provide the invisible scaffolding for human cooperation.

For instance, soldiers in the Indian military that come from different backgrounds and different parts of the country can come together on the battlefront to defend their shared belief in the idea of an Indian nation.

Millions of Christians around the world can commit to altruistic causes like building hospitals or helping the underprivileged because they draw from a shared moral framework that has been constructed based on the mythological story of Jesus Christ.

Engineers at Apple offices in different countries can work in harmony to meet quarterly goals because they are united by their commitment to a common employer, a corporate entity that has been summoned into existence via a few strokes of a pen, recorded in a few signed documents filed away with a corporate registrar in the United States.

Feuding political parties in the United Kingdom can agree to abide by the outcome of an election because they believe in the ethereal notion of ‘democracy’.

People around the world with nothing else in common can buy, sell and trade goods and services with their global counterparts because we collectively subscribe to the concepts of money and credit, and we trust that everyone else does as well. (The idea of) money makes the world go round.

Stories are everywhere. They bind us, define us and drive us. Author and scholar Jonathan Gottschall goes so far as to suggest that ‘Homo Sapiens’ (the wise man) is a far less accurate description for human beings than ‘Homo Fictus’ (the storytelling man). Many of the most foundational truths of human society today can be traced back to stories that originated hundreds (and even thousands) of years ago. These are often dressed up in colourful mythology and fantastical allegory in order to capture the attention of their intended audience and supercharge the lessons embedded in their message. For example, the threat of eternal damnation is presented in many religious texts as a deterrent to embarking on immoral activities. When all else fails, there is merit in applying a mystical or supernatural reason to buy in to age-old wisdom. As is clear by now, we are suckers for a good story.

“The faculty for myth is innate in the human race…It is the protest of romance against the commonplace of life.”

― William Somerset Maugham (The Moon and Sixpense)

The narratives that endure today reveal two important pillars of storytelling - the ‘story’ and the ‘telling’. In other words, both the message as well as the provenance of the message are important to the success of humanity’s most cherished fictions. For example, Apple benefits from Apple fanboys continuously blogging about the exceptionalism of Apple products, which in turn reinforces the story of Apple’s brand superiority in the minds of consumers. Supporters of Arsenal Football Club continue to sing songs about the glory days despite almost two decades of underachievement on the pitch. This isn’t because of some blind affinity for a silly corporate logo. Its because the mythology of the ‘Arsenal’ story still holds some metaphysical weight in their hearts. The players, the staff, the executives and even the stadium have all changed from when they first started supporting the club. But the songs remain the same. They bind the supporters of the club to the football team that takes the pitch every week with that badge on their chests. The songs keep the history and the glory of the club alive, and help to indoctrinate new fans to the supporter base even though the on-pitch product in recent times has often left a lot to be desired. Even the Catholic church needed its legion of missionaries to broaden the teachings of Jesus Christ around the world. However it was the invention of the printing press which eventually catalysed the spread of Christianity, helping to seed it as the ideological foundation of Western civilisation.

The point here is that humanity has always leaned on different mediums and devices to support and ferry its most compelling beliefs. The ideas that resonate with people, the ones we deem ‘viral’, are those that are most successful at infiltrating the ‘narrative receptors’ in our brains. They appeal to our visceral understanding of the world. They find a home in our conscious and unconscious minds, helping to shape our opinions and identities whether we know it or not. They compound over generations, becoming part of our collective history, helping to coordinate human beings across space and time. They take root as generally accepted cultural truths because we can’t help but spread them. That’s a feature, not a bug. In fact, we even have an innocuous term for these units of culture that propagate through repetition.

Follow The Meme

“We are all susceptible to the pull of viral ideas. Like mass hysteria. Or a tune that gets into your head that you keep on humming all day until you spread it to someone else. Jokes. Urban legends. Crackpot religions. Marxism. No matter how smart we get, there is always this deep irrational part that makes us potential hosts for self-replicating information.”

- Neal Stephenson (Snow Crash)

When evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins coined the word ‘meme’ in the final chapters of his seminal 1976 bestseller The Selfish Gene, he couldn’t have predicted how important his innocuous act of neologism would be to the native culture of the Internet (which wouldn’t even exist for another couple of decades). Intended to be a riff on the word ‘gene’, Dawkins suggested that memes were units of cultural information that served as replicators of human culture, in a similar way that genes were units of hereditary information that served as replicators of human life.

“Just as genes propagate themselves in the gene pool by leaping from body to body via sperms or eggs, so memes propagate themselves in the meme pool by leaping from brain to brain, via a process which, in the broad sense, can be called imitation”

Using a virus as a metaphor, Dawkins suggested that memes were capable of shaping and infecting the human mind with observations, concepts, ideas, theories, lessons and stories that migrate from person to person within a society. He would go so far as to claim that memes had become responsible for driving evolutionary change at a rate that their genetic cousins were no longer capable of matching.

A good meme is one that synthesises complex reality or information and converts it into a palatable form that can be easily understood. A meme has to be accessible in order to be shareable. If it doesn’t resonate with its intended audience, it has a limited chance of being spread further, which defeats the whole point of its existence. A meme is information that has been prepared for dissemination. It is content that demands to be shared.

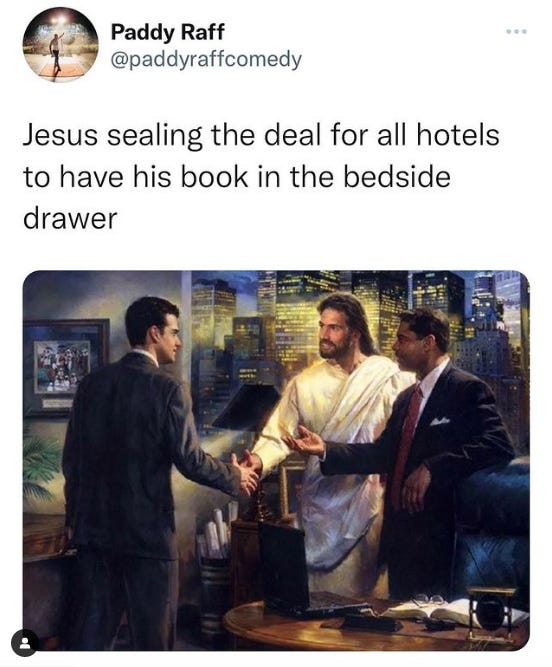

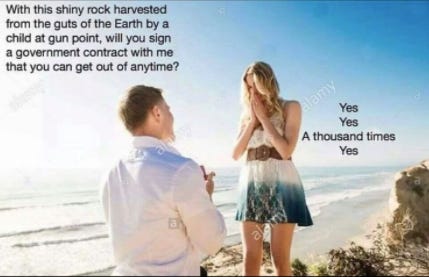

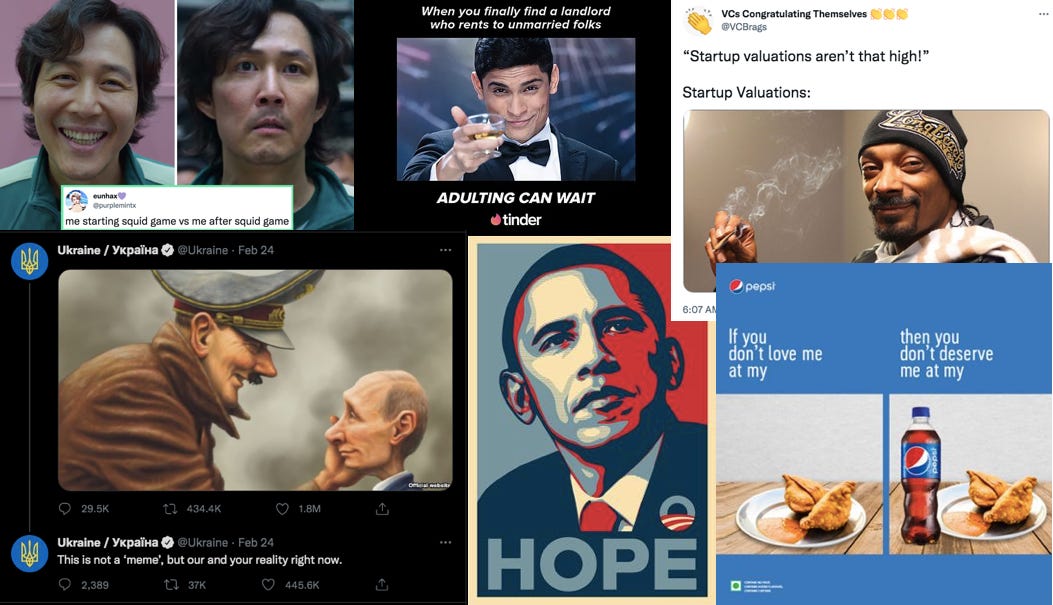

Legendary comedian Jerry Seinfeld once said that a joke is a ‘precision instrument’. A meme is kind of similar. It is a thought that has been packaged in a compact way that aids comprehension and transmission. Although most people think of memes today as funny pictures on the Internet, memes are really shorthand for any kind of idea or information that goes viral. On the Internet it just so happens to be the case that viral ideas are often packaged as funny images.

And not so funny images.

Sometimes even dank images.

But mostly just relatable images.

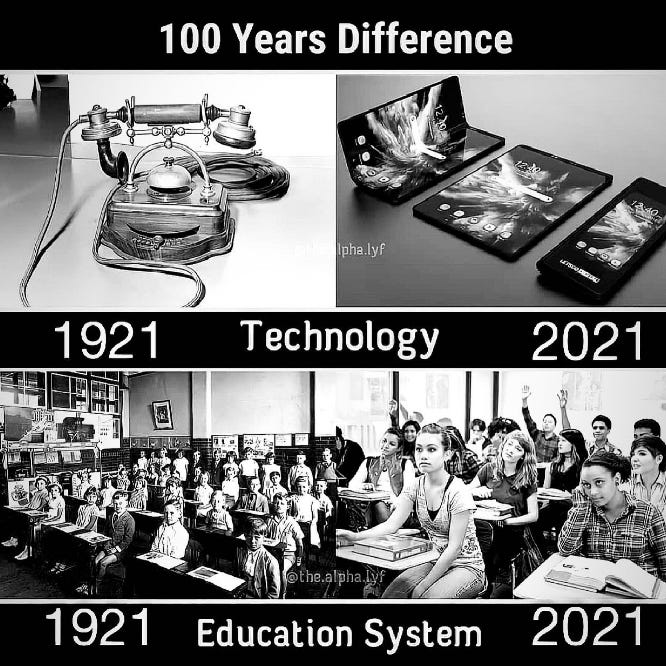

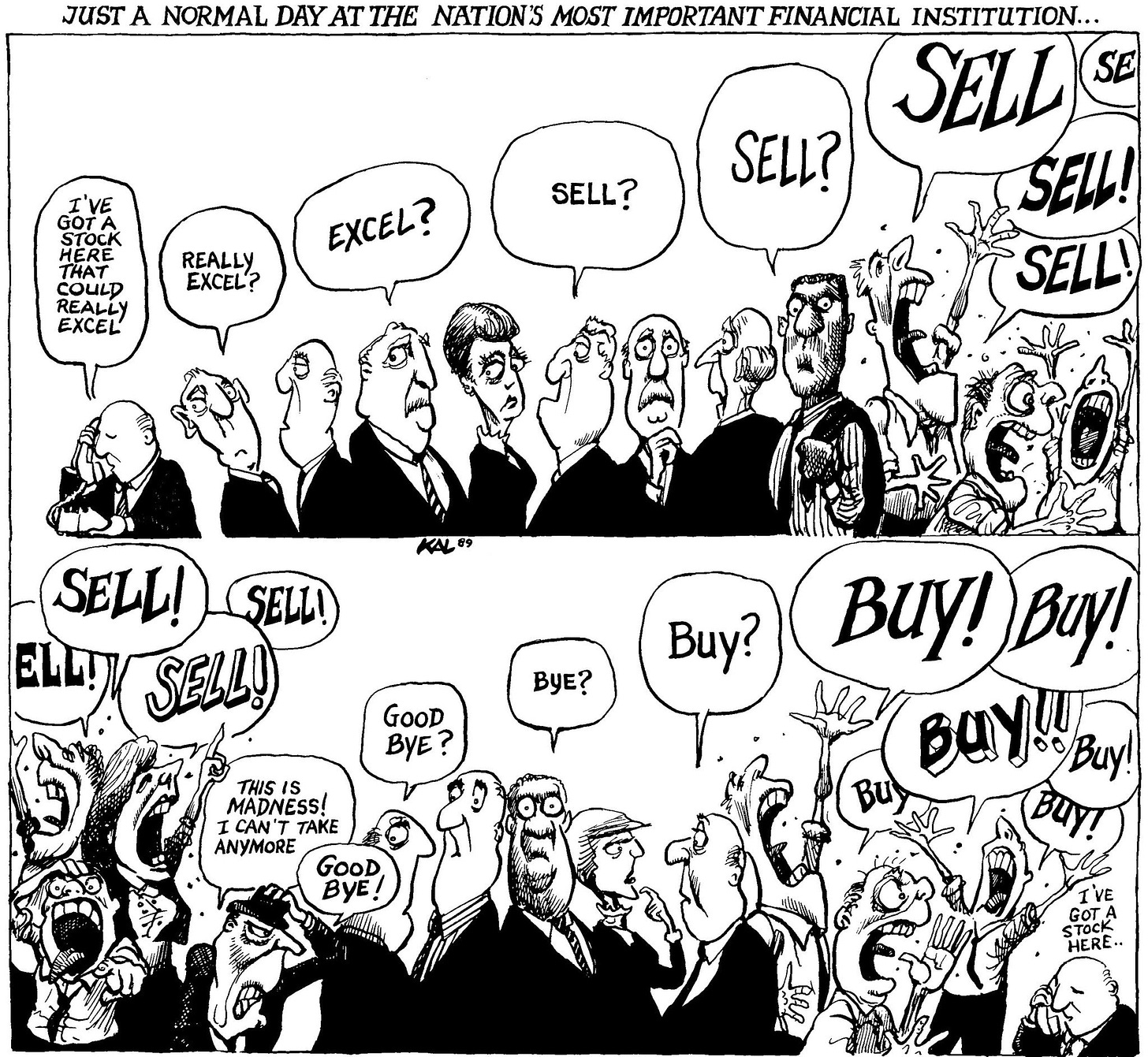

Modern society is full of memes (and not just the Internet variety). We live in an age of information abundance, which means we’re always on the lookout for intellectual tools that help us cut through the noise. Thats why you typically find memes in environments with low-time preference and high-information density, where people need to decode complex data to make quick decisions. Politics and financial markets are two notable arenas that have become fertile breeding grounds for societal memes.

For instance, the efficacy of the electoral contests that represent the climax of our democratic process is incumbent on the education and engagement of the voting populace. But it is hard for ordinary citizens to keep up with every little bit of political news or to be familiar with the nuances of every policy proposed by duelling candidates. So we defer to memes. For our Indian readers, think back to the 2014 General Election, where our current Prime Minister Narendra Modi made his ascent to political stardom. You probably don’t remember every important detail from the election. But you might be able to recall the memes that propelled his rise - ‘good for business’, ‘economic reform’, ‘anti-corruption’, ‘populist agenda’, ‘antidote to dynasty politics’. You could double-click each of these, but for most people the memes were enough to drive a decisive outcome at the ballot box.

To draw a parallel to the United States, former President Donald Trump was a master of memes (even if he wasn’t a master at much else). He was highly effective at compressing large amounts of dull political data into bit-sized content infused with provocative imagery - ‘Crooked Hillary’, ‘Sleepy Joe Biden’, ‘Jeff Bozo’, ‘Fake News’, ‘Build The Wall’, ‘Lock Her Up’. While other candidates banked on elaborate policy frameworks and traditional communication strategy, he consistently injected new memes into the cultural bloodstream of America which ultimately helped spread his message and capture the imagination of large swathes of a disenchanted American public. Scott Adams (the creator of Dilbert) even remarked that, for better or worse, Donald Trump’s oratorial style was more akin to that of a hypnotist than a politician because of his knack for implanting ideas into the minds of his followers.

Memes don’t just change minds, they move markets. So much so that we’ve even seen the emergence of an entirely new sub-category of public market assets - ‘meme stocks’ (which may as well be called ‘idea stocks’ or ‘narrative stocks’). Memes allow investors to condense large amounts of information into cognitive flashcards that aid swift decision making. For example, you don’t need to know how an electric battery works to invest in Tesla, because you’re not really investing in Tesla stock based on Tesla’s engineering prowess. You’re investing in the ‘meme’ of green energy companies being more valuable in the future because of the changing attitudes of society towards more environmentally responsible corporate governance. You’re betting that the potency of the ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance) meme will continue to propel your portfolio upwards. Memes like ESG spread like wildfire, competing against other dominant memes (eg: “Musk is an unhinged CEO”) to manifest a version of reality that reflects the consensus of a critical mass of market participants.

Private markets aren’t immune from this type of thinking either.

“Entrepreneur is a synonym for salesperson, and salesperson is the pedestrian term for storyteller” - Scott Galloway

Popular memes like ‘Uber-for-X’, ‘Every-company-is-a-fintech-company’, ‘the creator economy’, ‘the gig economy’, ‘Web3’, ‘Software Is Eating The World’ etc allow investors to create narrative models with which to evaluate potential portfolio companies. Of course, fundamentals do matter (for both private and public market valuations). Companies that are built on strong economic foundations will largely outlast those that are propped up by just hype and a good story alone. New York University professor Aswath Damodaran writes in Narrative and Numbers that “Valuation that is not backed up by a story is both soulless and untrustworthy…We relate to and remember stories better than we do numbers, but storytelling can lead us into fantasyland quickly”. The saga of Theranos and Elizabeth Holmes is a recent cautionary tale that demonstrates the persuasive rhetoric of a good story (“Underdog female founder”, “The second coming of Steve Jobs”, “Groundbreaking innovation in biotechnology”, “Democratise healthcare for all”) to obfuscate the instincts of even the most savvy investors, scientists and professionals. A good meme has the potential to sway the perception and trajectory of companies and people in the most drastic of ways. These are essentially units of cultural information that have immense financial and reputational consequences.

A close assessment of our social fabric today would reveal the integration of countless evergreen memes that have been interwoven into the rigmarole of human life. ‘Family values’, ‘social justice’, ‘individual liberty’, ‘capitalism’, ‘religion’, ‘charity’, ‘honest living’, ‘human rights’ - these are memes that have been passed down from generation to generation, calcifying at the substrate of human civilisation. These are the stories we tell about ourselves. They add profundity to the mundane and meaning to the meaningless, creating a richer prism through which to examine the human condition. They contain frameworks for social coordination and harmony. They are ideas that have been battle-tested over time and space. The societal memes that endure contain useful instructions for how we should live our lives both individually and as a collective. The ones that have ceased to be useful or have failed to hold up to the scrutiny of time (or science) are reclassified as superstitions and heresy. ‘Knocking on wood’, ‘walking under a ladder’, ‘opening an umbrella indoors’ etc are examples of outdated memes that continue to get airplay even in our hyper-modern world, demonstrating the potency of a well told tale.

When you add up the cultural totems that bind human society today along with the memes that that represent a consensus on our shared global memory (World War 1, The Invention of the Telephone, Indian Independence, The Renaissance, The End of Apartheid etc) you construct a fairly accurate picture of human history. We are getting increasingly good at recording these stories and arriving at an agreement around the sequence of significant historical events. Our news, our innovations, our rituals and our values are coalescing under a shared cultural canopy.

And thats because stories now move around the world at light speed.

The Memes of Production

“The Internet is a giant meme propagation machine”

- Chris Dixon (a16z)

For the vast majority of human history, the virality of an idea was limited to the size of the social group from which it originated. No matter how compelling your message or how convincing your mission, the proliferation of information was constricted by the boundaries of your immediate tribe. Local and regional myths stayed local and regional. Philosophy, fashion, craftsmanship and design flourished independently in different parts of the world. Roving bands of explorers and conquerers would play a key role in catalysing the cross pollination of cultures across land and sea. Missionaries and mercenaries would spread the gospel of religion and commerce, proselytising different philosophies and symbols that strangers could rally around.

The invention of the printing press in the 1400s expanded the surface area of human storytelling. It enabled us to record ideas, events and theories - to preserve knowledge in the amber of paper and ink. The Printing Revolution complemented the oral tradition of myth-making and governance that had gotten us so far in our evolutionary journey. It sparked the age of literacy, and with it a global awakening of education, art, scientific progress, economic upliftment, democratic tradition and religious faith. Information had been liberated. We had discovered a contemporary way to build our anthropological memory beyond the austerity of cave paintings.

Each new medium of communication added a layer of sophistication to humanity’s ability to get the word out and to bring people together. The telegraph, the telephone, radio and television each presented a richer way of engaging in dialogue with other people. The latter two in particular introduced the concept of mass media, where an individual could exert influence over a large group of people, maximising the leverage of any single message. Geographical separation mattered less and less as technology trivialised the physical distance between people. The addition of sound and colour meant that you had a versatile toolset to craft compelling narratives in service of specific objectives and undertakings (like going to war, electing a president, starting a commercial enterprise, advertising a product, presenting a scientific discovery, making a film, or laying the ground rules of a new country or religion).

And then the Internet happened. The ultimate equaliser. The modern printing press, one that reduced the time and cost of disseminating information down to zero. All media was now inherently social, capable of reaching, swaying and shaping the minds of people all over the world (on newsfeeds) in real time. We swapped local for global, inadvertently forcing native traditions to compete in a global marketplace of ideas. As a consequence of the Internet, we have become an international people with an unfettered conduit for sharing our cultures. Our memes are now globally significant cultural objects.

“The new electronic independence re-creates the world in the image of a global village.”

- Marshall McLuhan.

The Internet also catapulted us into an age of information abundance. Our challenge is no longer searching for knowledge but sifting through it to separate signal from noise. It makes sense then, that cyberspace would prove to be a fertile ground for the proliferation of memes. In a storm of infinite stimulation and data, memes help to cut through the fog, capturing the essence of ideas, behaviours and concepts in a succinct way.

Memes are the native language of the internet. They represent the most efficient method of getting a point across online. Internet memes are like digital mind viruses looking for hosts to infect. Social media is teeming with them. If you look under the wrong rock you expose yourself to the worst the internet has to offer (conspiracy theories, fake news, extremism, ideological partisanship etc). On the other hand, if you are fluent in Internet vernacular and understand the unspoken rules of digital virality, you can meme your way to great power, popularity, wealth and influence.

A good meme is just a well packaged story. In today’s age of perpetual digital connectedness, we collectively deconstruct news, pop culture and current events in real time using a meme-based filter. We rely on memes to dissect reality into easily digestible nuggets of information. When employed effectively, a meme can be a lightning rod for like-minded people - i.e. an idea, an image, a concept or symbol for people to connect over. Memes can be the starting point for new communities, similar to how a brand, a religion, or even a sports team help to unite people who see the world in a similar way.

This means that popular Internet memes have immense utility. They help to translate and transmit ideas within a society. They should be able command social and economic ‘value’ that reflects this utility. In fact, you would think that the individuals that have mastered this form of digital storytelling would be able to convert their social capital into financial capital. Shouldn’t the meme-makers be as important as the memes? Unfortunately today that’s not really the case. When it comes to monetisation on the Internet, individual media creators have often been left out out of value chain, unable to cash in on their cultural contributions. It is typically the social media companies that enjoy the fruits of this creative labour, benefitting from the increased frenzy (and data trail) that accompanies popular user-generated content (like memes) on their platforms. This is a challenge we’ve struggled with for the majority of the internet era.

How do you properly honour someone for their cultural contributions in cyberspace?

Can you own a meme? Can a meme have a market?

Can a piece of content have a price? Can a digital file command economic value?

Can something that is infinitely shareable still engender a fair return for creator of the original copy? How do you even know something is original on the Internet?

Is there a way to plug the gap between social capital and financial capital in the realm of bits and bytes?

The good news is that the Internet is currently in the midst of a structural feng shui, where foundational elements of the Web are being replaced by a new paradigm that tilts the balance of power from centralised platforms to individual users, creators and builders. Similar to how each new medium of communication throughout history has offered a fresh canvas for collective fiction, this shift will have profound implications for storytelling (and storytellers) in the digital age.

Content is Uncrowned

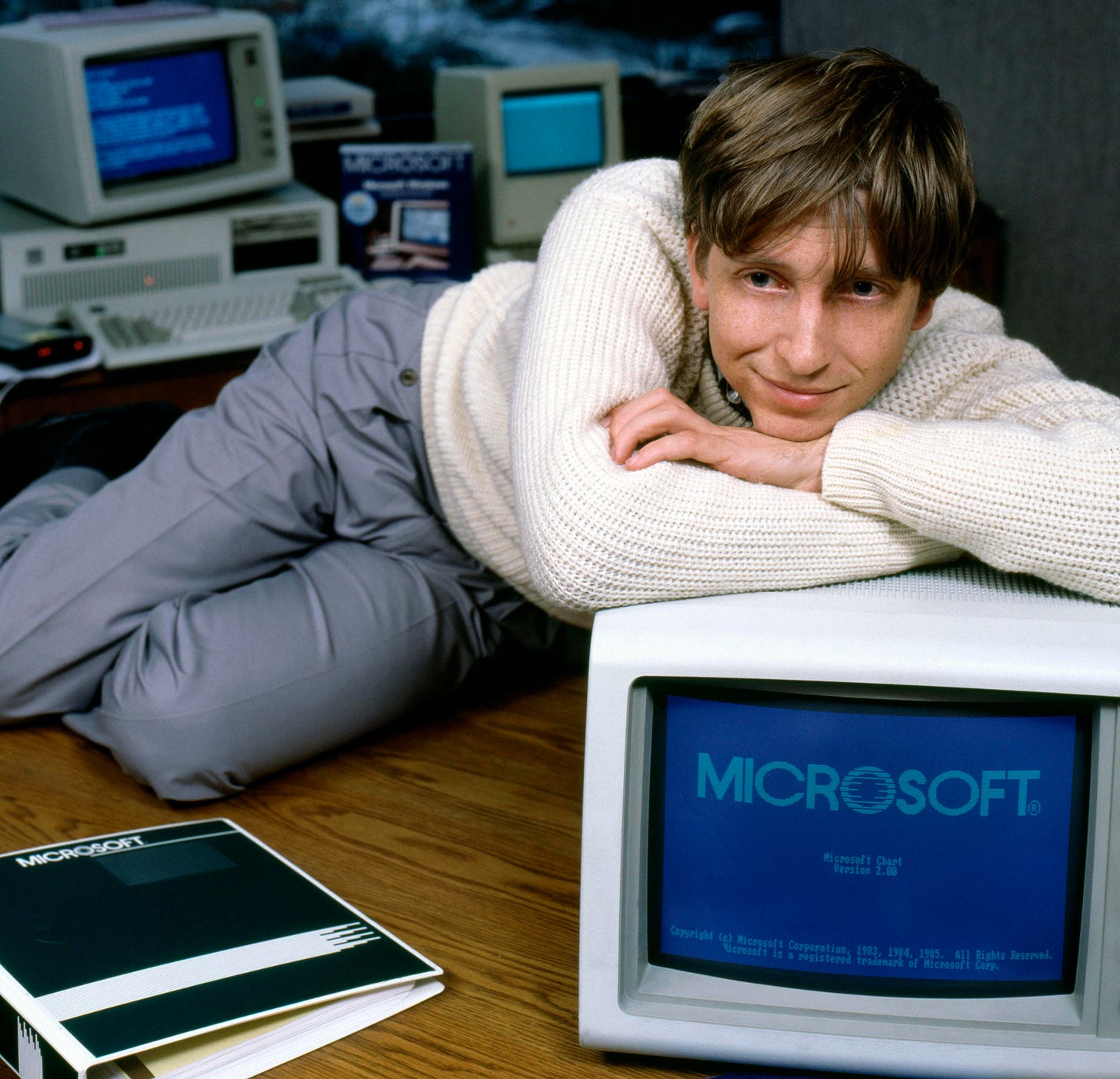

In 1996, Microsoft CEO Bill Gates would pen a seminal essay titled ‘Content is King’, where he would reveal his thoughts on the future of the Internet, ruminating that:

“Content is where I expect much of the real money will be made on the Internet, just as it was in broadcasting.

One of the exciting things about the Internet is that anyone with a PC and a modem can publish whatever content they can create. In a sense, the Internet is the multimedia equivalent of the photocopier. It allows material to be duplicated at low cost, no matter the size of the audience.

For the Internet to thrive, content providers must be paid for their work. The long-term prospects are good, but I expect a lot of disappointment in the short-term as content companies struggle to make money through advertising or subscriptions. It isn’t working yet, and it may not for some time.

So far, at least, most of the money and effort put into interactive publishing is little more than a labor of love, or an effort to help promote products sold in the non-electronic world. Often these efforts are based on the belief that over time someone will figure out how to get revenue.”

His essay would prove remarkably prescient in a number of ways. First, he pointed out that, similar to the television revolution that preceded the internet, the spoils of the Internet age would be enjoyed by the individuals and institutions that used this new medium to deliver content that was informative and entertaining (his definition of content included games, sports, software, advertising, news and media catering to niche communities). Second, he correctly predicted that content creators would have a tough time monetising their work on the Web.

Because the Internet had reduced the marginal cost of replicating and distributing information down to zero, it was difficult to ascribe value to any individual piece of media considering it could be infinitely duplicated. Exacerbating this was the lack of a native payments protocol for the Internet, meaning that people couldn’t directly pay for the content they liked via tipping or subscription arrangements. It wasn’t practical (or cheap) to make small-ticket electronic transactions. People were also reluctant to share their banking and credit card details with strangers online. This resulted in advertising becoming the default method of monetising attention on the Internet.

Another legendary Internet pioneer, Marc Andreessen (who founded Netscape, the company that built the world’s first commercially successful web browser called Mosaic), refers to this predicament as the Internet’s Original Sin. Andreessen laments his failure to convince banks and payment processors to work with Mosaic to integrate payments directly into the browser, which would have allowed people to directly pay for the content and services that they liked/used. The Internet was still too esoteric in the mid-1990s, which scared off traditional financial intermediaries and payment networks from getting involved with the Web. This meant that advertising became the only viable business model for media, because it was the only monetisation route that didn’t require individuals to exchange sensitive financial information with strangers over the Internet. Thus, people were effectively indoctrinated to assume that content would always be free and/or subsidised by advertisers. A pernicious dependence on advertising has spawned many of the issues we have on the Internet today that stem from a need to keep individuals hooked to their screens in order to harvest user data. It is the root cause of incentive misalignment between Internet users and Internet platforms.

To illustrate, lets say you created a funny meme that managed to perfectly tap into the zeitgeist of the 2020s.

Lets say that meme then went viral on Twitter garnering millions of impressions. You’ve now created something that has measurable ‘cultural’ value. You’ve told a story that people resonate with. Your image could become a recognisable image/symbol online, with its own community and sub-culture. You’ve now earned social capital. However, even as the original creator of the meme you would find it hard to extract value from your creation because it would be difficult to ascertain which of the millions of remixes floating around online was the original. It would also be a challenge for you to verify that you had created the original image. You would have to be content with a scant reward of likes, retweets and hearts as a validation for your efforts, but no way of directly monetising your creative output. Tipping and subscriptions are viable options only for a miniscule selection of online creators.

The real beneficiary is the underlying social media platform you use to get your message out. It is still practically impossible for the vast majority of independent media creators to get fairly compensated for their creative efforts on the Internet despite the cultural impact of their work. A second order effect of this, is that in the digital age the spoils of good storytelling and content creation are largely enjoyed by those with big budgets (i.e. brands, studios), valuable intellectual property (i.e. streaming services), or those offering advertising-subsidised content that caters to the lowest common denominator (i.e. the mainstream media). Thats why cultural clout is largely centralised. Thats why mainstream culture has been predominantly shaped by a clique of powerful studios, production houses and talent agencies, and not by individual creators. It boils down to a failure to validate the notions of scarcity, authenticity, and ownership of media in a digital setting.

For much of the Internet era we didn’t have a solution to this problem. But we do now.

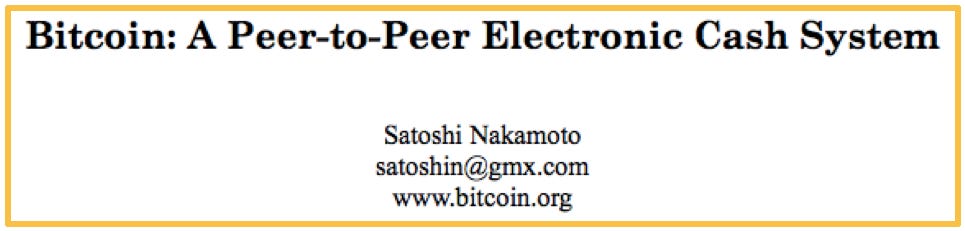

In October 2008, in the wake of the Financial Crisis, a person (or group) using the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto published a blogpost in an obscure online mailing list that would lay out the blueprint for a novel monetary system for the Internet. This system (called Bitcoin) would allow people to send and receive money online without going through any traditional central intermediary like a bank or payment network. It would employ the clever use of cryptography and game theory to ensure that each participant on the network was financially incentivised to act in the best interests of the system, removing the need for central authority or arbitration. Three months later, Satoshi would release the source code for his new idea. Anyone in the world could download the Bitcoin software (for free) and join the network. Anyone with an Internet connection could then use this network to exchange value online using its native currency i.e. Bitcoin.

You might be wondering about the relevance of a decentralised monetary network to the economic prospects of meme-makers and content creators in the age of the Internet. That’s fair. Satoshi’s invention was actually a breakthrough for a number of reasons. For starters, previous attempts at building an Internet-native system for digital cash had run into many of the same problems that creators have with extracting value from online media. Namely that it is difficult for a digital file to hold value if it can be indiscriminately replicated. You can understand why this issue would be a non-starter if you were trying to invent a new form of digital cash (i.e. your magic internet money could never be worth anything if I can just copy-paste it to infinity). The genius of Bitcoin lay in the application of several technological innovations that would preserve the integrity of such a system.

Although the intricacy of how Bitcoin works is beyond the scope of this essay, there are a few important ‘firsts’ that Satoshi introduced into the broader techno-cultural lexicon that are worth understanding:

The concept of cryptocurrencies or crypto tokens, which are units of software created by code that are used as vehicles to represent and transfer value over the internet.

The use of a system of distributed ledgers secured by cryptography that would allow every participant on the network to track the origination, ownership and provenance of each token through the entire history of the Bitcoin network. This system is called a blockchain (because transactions are recorded in a series of batches or ‘blocks’) and essentially functions as a decentralised accounting system for digital assets.

Satoshi chose to limit the total supply of bitcoin to 21 million, meaning that the price of a single bitcoin was designed to appreciate over time as more people joined/used the network. Coupled with the use of a blockchain to track the movement of each individual bitcoin, this would introduce the concept of digital scarcity i.e. a provable way to verify the authenticity and finite supply (and thus, the value) of a digital file or unit of media. This means that if you tried spending the same bitcoin in two places, the network would reject the second transaction as invalid if it discovered that the token had already been spent somewhere else.

If digital assets can provably hold value, then there is now merit in provable digital ownership. The Bitcoin network uses cryptographic techniques to secure identities and transactions on the network. Your identity on the network is pseudonymously represented - it is a unique string of letters and numbers as opposed to a conventional username or email address. Your identity is yours alone to manage, thanks to a cryptographically generated public key (i.e. your Bitcoin username) and private key (i.e. your Bitcoin password). Without your private key, no one can seize or censor the digital assets (i.e. Bitcoin) that you hold in your digital wallet. With your private key, you have sole ownership and control over your bitcoin. Unlike your social media profile, no corporation or government can take these away from you.

The concept of programmable money, where digital assets can be programmed to act in a certain way based on the satisfaction of pre-determined criteria. For example, if I can provide a digital signature using my private key that corresponds to the wallet address where my bitcoin is held, then I have the right to send that bitcoin to anyone on the network. The rules of the Bitcoin network are enshrined in its code, meaning that the network will continue to function as long as the pre-defined conditions are met, without the need for any kind of arbitration from third parties (like lawyers or accountants). These self-executing ‘contracts’ embedded in code are known as smart contracts. They exponentially increase the potential for innovation in digital commerce.

Bitcoin would launch us into a new chapter of the Internet. It would spark an entire ‘crypto’ industry with sophisticated applications and services built around the idea of decentralised blockchain-based protocols and provably scarce digital assets. Most importantly, for the purpose of this essay, it would provide cultural contributors (artists, community-builders and marketers) with a new canvas for storytelling and creative expression.

NFT - No Fleeting Trend

Satoshi envisioned Bitcoin to be a better form of money than our prevailing government issued currencies. His objective was to conceptualise a better way of sending and receiving payments in the digital age that reflected the ease with which we can transfer electronic data over the Internet (i.e. quickly and cheaply). However for bitcoin to work as a viable monetary option, it needed to fulfil certain functions that we’ve come to expect from any commodity that has been historically adopted as ‘money’. It needed to be:

Durable - Money should be able to withstand degradation from repeated usage, storage and the passage of time

Divisible - Money should be divisible into smaller units or denominations

Portable - People should be able to carry money around with them and transfer it to others

Scarce - Money should be widely available yet not easily created or found

Fungible - Each unit of money should be interchangeable with any other unit

The last point is where things get interesting. For Bitcoin to be generally ‘acceptable’ as a form of money to be used widely in commercial transactions, each unit of Bitcoin needs to be uniform. There can be no characteristic difference between one bitcoin and another, just like there’s no economic difference between a single hundred rupee note and another. For a digital cash system (like bitcoin) to work, every monetary unit needs to be verifiably fungible i.e. perfectly exchangeable.

But that same requirement doesn’t extend to the rest of our digital lives. In fact, most of the objects in our physical world are non-fungible. They are unique. And they derive their uniqueness from the specific ways in which they enrich our lives - serving as a form of expression, identity, utility, sentiment, entertainment, status or wealth. They derive their value not from their material disposition but from how they enable us to tell our own stories.

“Saying that cultural objects have value is like saying that telephones have conversations.”

- Brian Eno

We have so far lacked a way to replicate the same function in a virtual setting (despite the fact that we now spend a meaningful portion of our lives online). This has stemmed partly from a lack of technical infrastructure to express the uniqueness of digital goods. And partly from an inability to attach economic value to infinitely replicable digital ‘assets’. At some point in the last 14 years, this ceased to be a limitation. Bitcoin (and blockchains) validated that you could in fact provably demonstrate scarcity in a digital setting, meaning that you could create a logical foundation for why certain digital media could command an economic value. Cryptographic primitives like wallets, digital signatures, public keys and private keys allow individuals to exercise indisputable ‘ownership’ of digital assets, with public blockchains creating an immutable record of scarcity, authenticity and provenance.

Building on the philosophical underpinnings of Bitcoin and the design principles of public blockchains and crypto assets, the last decade has seen the blossoming of an entire crypto industry that has endeavoured to apply the same technological toolset to use cases beyond ‘money’. We’ve seen general purpose blockchain platforms (like Ethereum) provide the foundation for countless colourful experiments that collectively make up a vibrant ecosystem of decentralised applications. Arguably the most important development of all is the emergence of a new technical standard for representing unique digital assets, something we now commonly refer to as Non-Fungible Tokens or NFTs.

An NFT is a bit of code that exists on a blockchain that serves as a certificate of ownership for a unique digital asset. The token can contain reference to a piece of content or media like an image, video, gif, song, document, game item, ticket etc (the content isn’t the NFT, the token is the NFT). The NFT acts as a receipt, providing publicly verifiable proof of ownership for the holder via the magic of blockchains and cryptographic keys. They allow anyone to inspect the authenticity, scarcity, provenance and ownership of a particular NFT. Because these are programmable cryptographic tokens, they can come with specific rules that expand their functionality. For example, an NFT can come with the condition that a fixed percentage of every future sale will be paid out as a royalty to the original artist in perpetuity. The NFT doesn’t necessarily prevent someone from using or consuming the content it references. You can still view an image or listen to a song that has been created (‘minted’) as an NFT. It just means that only the owner of the NFT (who holds the private key of the corresponding crypto wallet) is empowered to extract the economic value accruing from ownership (eg: to sell or transfer it, to license the content etc).

Despite a scattering of early NFT projects that were launched on the Ethereum blockchain (and a few on the Bitcoin blockchain) between 2014-2020, NFTs only really entered broader public consciousness in 2021. If you weren’t already familiar with the nuances of crypto, chances are that’s when most readers were introduced to the concept of NFTs as well. But the manic price action and speculative mania has muddied the general perception of what NFTs can be. Most people think NFTs = irrationally expensive pictures of cartoon animals that are of dubious quality. If you were judging this technology by last year’s market action alone, that statement isn’t entirely untrue. But in reality, NFTs represent the beginning of a new era of digital creativity and digital commerce, one that is already challenging our understanding of ‘value’ in the Internet age.

Analogous to websites or mobile applications, NFTs represents a whitespace for online imagination. It is a fresh canvas onto which we can project media and conduct commercial activity. As a blockchain-based cryptographic token, an NFT is a versatile piece of software that can be moulded to fit a variety of use cases. Each token is freely tradable via online marketplaces where the forces of demand and supply can determine the price of a particular NFT. Artists, creators, brands and builders have already begun to test the creative limits for infusing cultural and economic meaning (re: value) into provably scarce digital objects. In the bargain they’ve discovered clever ways of using this digital scaffolding to tell stories, forge communities and make a living online.

Some of my favourite examples and use cases include:

1. Allowing artists to monetise their work by adding scarcity to digital content

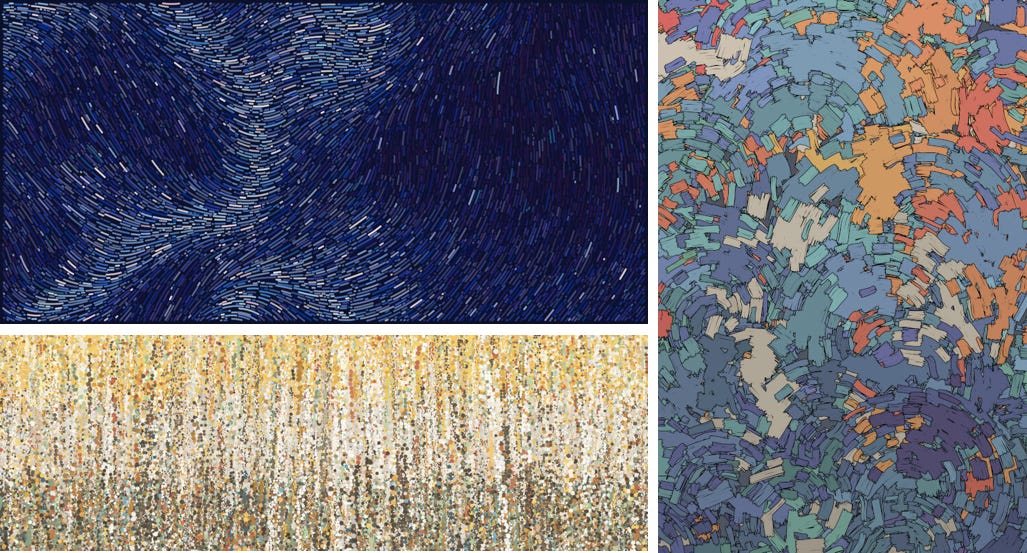

Tyler Hobbs is a visual artist from Austin, Texas. He specialises in generative art, which is a genre of graphic illustration centred around creating computer algorithms that are programmed to generate visual imagery. The role of the designer is part software engineer and part artist. The artist prescribes certain inputs (eg: shapes, concepts, angles, colours) and the computer does the rest. For almost a decade, Hobbs has been a pioneer and a thought leader in this space, creating programs (and artwork) that have challenged the notion of what it means to be an artist, and whether machines are capable of creative expression.

Despite amassing a respectable global following and having his work featured in art galleries around the world, Hobbs’ talent for generative art was relegated to being a passion project as opposed to his main profession, because he could never figure out how to monetise his output. As a digital artist, if someone wanted to collect or acquire his work, that essentially meant Hobbs would send them a JPEG file as an email attachment and invoice them a nominal fee for doing so. How are you otherwise supposed to convince a buyer to spend a large sum of money on a digital file that can be infinitely copied and pasted?

There was a missing link in the patronage of digital art because it was hard to define what it meant to really ‘own’ a piece of digital art. Then in June 2021, Hobbs would release a now iconic series of 999 art pieces as NFTs, as part of his signature ‘Fidenza’ collection. It was a culmination of his life’s work, and would sell out instantly for a price of ~$400 per NFT. Since then, the collection has done a total trading volume of 43.4K Ether (~$1.3 billion), with Hobbs having earned $9 million in royalties as a fixed percentage of every secondary sale (as per Dec ‘21). A single Fidenza now goes for close to $150000.

Releasing his Fidenzas as NFTs gave his audience a tangible proof of authenticity, scarcity and ownership of his artwork that they could enjoy (and flex). It converted his art into a tradable asset. Blockchains represent an economic layer for content on the Internet, which means that NFTs essentially create a market for memes. The image/gif/song/meme is still infinitely shareable and remix-able, but the original media creator is now also able to fairly monetise their work because people appreciate the opportunity to own and invest in cultural artefacts. Online NFT marketplaces provide transparent price discovery for digital assets and a history of provenance for each NFT. Fans of Tyler Hobbs’ work can now support his art either as collectors, patrons, aesthetes or speculators.

A picture may be worth a 1000 words, but an NFT is ultimately worth whatever someone is willing to pay for it. Traditional gatekeepers and curators no longer have a monopoly on legitimacy - the free market becomes the chief arbiter when it comes to determining the value of a cultural artefact. The best content will find a natural home on the blockchain.

2. Seeding new communities by forging ‘bottom-up’ brands

The Bored Ape Yacht Club (BAYC) is a collection of 10000 NFTs that feature images of cartoon apes (that you’re probably familiar with already), with each token doubling as a membership to an exclusive community that grants holders with certain virtual and real world benefits. Each Ape has been generated algorithmically, based on a random combination of traits and features (fur, background, headgear, outfit etc) that mean each NFT is provably unique. The variation in the frequency of certain traits occurring creates an objective difference in the ‘rarity’ when comparing different Apes in the collection. Launching in April 2021, each NFT was originally offered to the public at a price of ~$200, and the collection took a whole week to sell out. BAYC also granted each of its holders full commercial rights over their Apes, meaning that users were encouraged to find creative ways to use their NFTs as part of their personal or commercial branding.

In less than a year, BAYC has become a cultural force, stirring up a dizzying amount of attention and social capital. This was largely due to the unprecedented step of giving holders full commercial rights over their NFTs. Individual Ape holders have signed lucrative talent deals to be the face of music groups, nightclubs, novels, comic books and consumer brands. Many of these individuals are only known pseudonymously (i.e. they are only known by their NFT avatars). Bored Apes have appeared everywhere from music videos to talkshows to NBA players’ footwear. BAYC has launched a mobile game and merchandise partnerships with high profile fashion brands. As their social recognition has grown, so has the value of an individual Bored Ape NFT, which now sits at a minimum price of around $300000, with ‘rarer’ apes regularly selling for millions of dollars. They are a perfect (and lightning quick) example of a Veblen good, which means the demand for a Bored Ape has increased as the price increases, similar to a Rolex or a Lamborghini.

Whereas early BAYC buyers were mostly made up of a crypto native audience, over the last 12 months high profile influencers, entertainers, professional investors and celebrities have FOMO’d in to the collection, now using their Apes to signal their wealth, status or trendiness online. This in turn increases the appeal of the project, because people want to be part of the same ‘club’ or social network as their idols. BAYC also accelerated the trend of Profile Picture projects (PFPs), where NFTs in a collection were designed to be used as your avatar on social media, to signal one’s belonging to a particular group. At this point, owning a Bored Ape (or using one as your profile picture) signals that you were either savvy enough to be early to the trend or rich enough to purchase one later on or rich enough now because you were early to the trend (h/t Packy McCormick). In other words, NFTs are probably the greatest thing to happen to hipsters since the invention of the handlebar moustache.

To a non-crypto audience, people shelling out millions of dollars for pictures of cartoon apes might seem absurd, till you look under the surface at what’s really happening here. The first wave of popular NFTs have tended to be JPEG-driven (re: image driven) only because NFTs are an inherently social technology. On our current social media platforms, profile pictures are arguably the most valuable form of real estate. Similar to a clothing brand or a football team, using NFTs as your profile picture is a way to signal one’s affinity to a particular group or cause (even if that ‘cause’ is just an appreciation for a certain artist, creator or character). NFTs contextualise online communities. They represent symbols or totems (re: logos) that people can rally around, almost like digital campfires. This is meme culture with an economic component. Buying an NFT is no different than buying a T-shirt from your favourite band or jersey from your favourite team. It is an extension of your personality and a way to express your online identity.

Popular NFT collections are just popular consumer brands in disguise. The difference is that instead of Nike or Apple driving the growth of the brand by tightly controlling the messaging and product roadmap, with NFTs the community is part of the process right from the jump. People that resonate with a particular concept, mission or aesthetic can buy into an NFT collection, helping to instantly seed the project with funds as well as a loyal fan base. NFT holders are then incentivised to use their NFTs in interesting ways that increases the social recognition of the project because the acquisition of cultural value will ideally filter down to an appreciation in the price of each NFT in that collection. They are incentivised to help tell the story of the community they have joined, acting as quasi-endorsers of a brand (similar to how Lebron James or Serena Williams help to tell the story of Nike by wearing Nike shoes while they play). People are incentivised to organise events, buy merchandise or play games that features their NFTs and to use them as part of their social media profiles. Owning the token in many cases grants holders exclusive access to content, items, experiences and chat groups where they are empowered to exercise opinions and governance on the future direction of the project.

This isn’t to say that every low-effort derivative NFT collection hoping to capitalise on the success (and quick gains) of BAYC will be destined for success. The vast majority are heading to zero, and will likely fade away once the initial buzz wears off (though they could still have artistic or sentimental value to their buyers). But the NFTs that manage to strike the right chord with the right community will become the starting point for the most popular global entertainment and fashion brands in the years to come. They may even become interoperable social networks themselves.

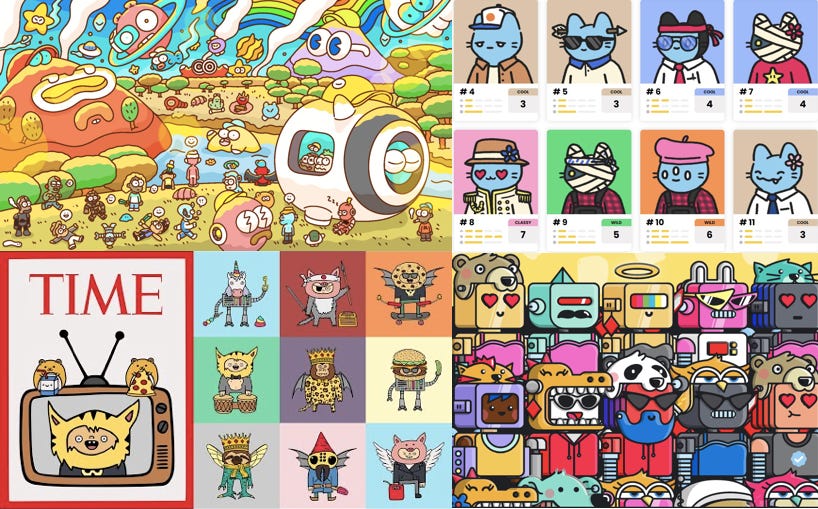

3. World-building via the creation of new intellectual property

Because Bitcoin’s original aim was to build an alternative to the global monetary system, crypto was always assumed to be a disruptor of Wall Street. However in the decade since, the proliferation of other public blockchain platforms and decentralised applications mean that crypto also emerged as a decentralised alternative to Silicon Valley. Now, with NFTs, crypto has finally come for Hollywood too.

Brands and studios no longer have a monopoly on large-scale storytelling. The next great movie franchise or cartoon show doesn’t have to come from a traditional entertainment company with deep pockets. Global, pseudonymous 24/7 crypto markets mean that anyone in the world can corral financial support for an artistic endeavour. NFTs have provided creators with a way to build thriving ecosystems around new intellectual property in a way that gives their fans a share in the upside via ownership of characters, game items, virtual real estate etc that helps foster both an emotional and a financial connection to a new project.

Imagine if Walt Disney had launched his cartoon company in the 1920s as a collection of NFTs that featured his most iconic characters, with a vision to build an entire media empire around his creations. People that liked his work could purchase these NFTs, providing him with the funds to start his project. These buyers would now be financially invested in the success of his venture, helping to increase the recognition of his characters amongst their social circles and create new fans. Every time Mickey Mouse or Goofy were used in a popular film or TV show or toy collection, their cultural value would increase, with this value being reflected in the increase in price of the associated NFTs. NFT holders could also be given the rights to weigh in on the future of a certain character, or the merits of a particular commercial deal. Depending on the IP arrangement, they could even be free to look for economic opportunities for the individual characters that they ‘owned’. The success of an individual character would also filter value back to the overall brand, creating a positive flywheel of value creation. Disney could keep widening his ambitions, safe in the knowledge that his cultural and financial capital was increasing as more people became aware of his project, incentivised to also own a piece of their favourite franchise as well.

This arrangement is par for the course in NFT land. NFTs have sparked a digital renaissance around new intellectual property. Talented creators have built entirely new franchises around a set of animated characters with properly incentivised communities helping to spread awareness and acceptance of each project. Any fan made content or memes featuring these characters would filter back to an enrichment of the individual NFT holders. Using NFTs as a creative medium means that potential fans have a way to come along for the ride, buying NFTs that match their personalities and interests (or desire for financial return). Investing in NFTs, then, is like “angel investing in culture”.

In the last 12 months we’ve seen NFT projects like:

Robotos (a collection of cartoon robots created by Pablo Stanley) and Toy Boogers (a hand-drawn series of animated boogers by Doug) both sign commercial deals with TIME Studios to create franchises (TV shows, movies) for children built around the popularity and family-friendliness of the underlying NFT connections. Creepz (an NFT project that lampoons conspiracy culture on the Internet) recently inked a deal to be represented by global management and entertainment company Three Six Zero to grow their brand into a full fledged media empire.

Cool Cats (a collection of cartoon cats built around original artwork from Clon) evolve into a full-fledged Pokemon-style game with its own digital universe, where players can breed their cats, collect items and earn rewards (all as fungible and/or non-fungible crypto tokens), essentially earning real dollars by putting their NFTs to work

Loot, a collection of 8000 NFTs, each just featuring a list of words/items on a black background (meant to represent ‘bags full of loot’), pioneered a new template for community-based online gaming. The project is based on community members taking inspiration from the NFTs to build out the Loot universe in any way that they can imagine - with characters, maps, art and adventures being designed by members based on the NFTs from the collection (i.e. a form of NFT improv).

Pudgy Penguins (a collection of uh pudgy penguins) demonstrate the power of a decentralised community, when NFT holders essentially ‘voted’ out the founding team of the venture, forcing them to sell the project to an external buyer as a consequence of mismanaging the IP and failing to deliver on their promises.

Each of these collections aims to keep their communities happy by organising events, conducting games, offering merchandise that lets holders rep their favourite projects, and ‘airdropping’ or gifting their holders new companion NFTs or free crypto tokens (almost like dividends) that incentivise them to stick around. Most popular NFT connections will offer some combination of aesthetics and utility.

NFTs unlock culture as an asset class. They make culture ‘investable’. They allow people to participate and benefit from storytelling at scale. NFTs are a tunnel through which value flows between creators, content and communities. Thats why the next big entertainment franchises won’t start as comic books or games, they’ll start as NFTs.

4. A new way to engage with an audience

If NFTs become the default standard for representing digital goods, this will have huge implications for corporations and brands that currently employ a variety of traditional marketing approaches to interact with their fans and customers online. NFTs are the cultural building blocks of the next iteration of the Internet, and brands want to be seen as culturally relevant. If the previous benchmark for good marketing was creating content that went viral, then NFTs greatly expand the surface area and even the definition of good corporate communication.

Almost every major consumer facing corporation has experimented with NFTs in the last 12 months. Already we’re seeing emerging trends where:

Companies like Budweiser (beer.eth) and Puma (puma.eth) are buying their domain names on the Ethereum blockchain (as NFTs), indicating their intent to establish a presence and conduct commerce in this crypto-fied (i.e. Web3) Internet landscape, which is similar to buying website domains in the early days of the Internet.

Companies like Visa, Puma and Adidas are buying high profile NFTs like Cryptopunks, Cool Cats, and Bored Apes, respectively, as a way to signal their intent to authentically contribute the NFT world, as well as tap into the individual communities of the NFT projects they’ve joined. Not only do these companies piggyback on the credibility and clout of the Cryptopunk, Cool Cat and BAYC brands (which gives them instant commercial visibility), but the NFTs that they buy as a marketing cost can actually turn into income generating assets on their balance sheets. If their NFTs appreciate in value, the companies actually make a gain on their marketing expense. That’s the real story here.

Companies like Adidas and Nike are either building or acquiring full-fledged NFT projects that seek to provide holders with digital and real-world experiences like exclusive merchandise drops, token-gated content, and branded digital collectibles. Any company that has existing valuable IP like the NBA, UFC or Marvel is launching NFT collections as a way to diversify their product lines and extend their IP. Established brands like Gucci, McDonalds, Lamborghini and Louis Vuitton have also jumped into the digital fashion/collectible game. They’re using the versatile canvas of NFTs for innovative storytelling like commemorating a pop cultural moment, creating privileged membership programmes or designing digital merchandise (that doesn’t require physical supply chains or counterfeit checks). This also applies to athletes, influencers, entertainers and independent creators who want to monetise and engage with their audiences, or raise money for a good cause. These NFTs give their fans a new way to interact with and extend their association with their favourite brands and creators. Brands can also segment their audiences, identifying the super-fans that want to hold their NFTs.

All manner of companies including the likes of JP Morgan and Samsung (Decentraland), PwC, Atari, and Adidas (Sandbox), and several others are spending real dollars to buy plots of virtual land (as NFTs) in ‘virtual worlds’ (Metaverse projects) that are being built on top of public blockchain platforms. The idea is that they can use this digital real estate to build virtual HQs, launch products, conduct events like fashion shows or concerts, or just hold the NFTs as an investment (because each platform has its own ‘limited’ supply of land). This might seem ridiculous to outside observers, until you realise that these virtual worlds are essentially the next iteration of our social media platforms. Its where the Internet’s attention and creativity is being diverted. Its where people will socialise, work and transact in a digital setting, moving from 2D newsfeeds to rich 3D environments. Companies want to establish a presence in the Metaverse to find new touchpoints with their customers, expand their product lines, and to design new digital experiences.

Its important to note that we’re only in the first innings of mainstream NFT adoption. A lot of corporate NFT projects are silly and sometimes even cringy efforts at hopping on a trend (no different than the early efforts of companies to build an Internet presence or a social media presence). But there’s something to be said for brands that are at least taking the time to play around with NFTs to figure out what works. This technology isn’t going away anytime soon. In many ways NFTs present a new challenge and opportunity for marketers. Customers that have loyalty to a particular brand are willing to buy their NFTs because they get an asset in return that has utility (exclusive access and rewards) and potentially even financial upside. These NFTs act as a cross between digital merchandise and a backstage pass, giving holders a new way to support their passions and express themselves online. Ultimately brands and creators will use NFTs to recognise and reward their most loyal fans.

You might still be unconvinced. You may still think that NFTs will fade away after the novelty wears off. Most current NFTs probably will. But we’ve only seen a sliver of use cases so far. Its worth noting that NFTs don’t fundamentally change human behaviour, but they do give us a novel platform for expressing human behaviour online. If you’ve only read the headlines in the past year and come to the conclusion that NFTs are dumb, you should consider that human beings already:

- use Snapchat filters and Instagram stories as a way to express ourselves online

- use social media posts, profile pictures and status updates to shape and curate our online identities

- use memes as a way of socialising online (to build bonds, spread information and entertain each other)

- spend money on physical merchandise (jerseys, t-shirts, toys etc) from our favourite teams, brands and artists

- spend money on virtual items like clothes and avatars within popular online games

- buy tickets, access passes or membership to various clubs and communities

- collect culturally significant items like shells, beads, marbles, gemstones, stamps, sneakers, Pokemon cards, blue check-marks etc

- confer sentiment and communicate status through our possessions like family heirlooms, artworks, memorabilia, hand-me-downs, fancy cars and watches etc

- own physical and financial assets for their utility and promise of future returns

NFTs give us a way to do all those activities in a digital setting. Programmatic cryptographic tokens allow us to reimagine the limits of commerce and creativity online. Imagine if you could fractionalise ownership of NFTs or use high-value NFTs as collateral to obtain a loan. Or use your NFTs as an entry pass to social clubs and events. Imagine designing products and services just for holders of a specific NFT as a way to curate a bespoke social network. There’s a long way to go till we find the most effective way to utilise this new medium. For now its worth remembering that the Internet is a global stage, and NFTs just give us a digital way to take human behaviour and dial it up to a 1000 (for better or worse).

So if human beings are storytelling animals;

And the internet is a storytelling medium;

And memes are units of information that shape culture and unify communities;

Then NFTs are the memes of the Metaverse, serving as vehicles to transport both cultural and financial value in a digital setting.

Closing Thoughts

In 1911, an Italian handyman by the name of Vicenzo Peruggia would steal a painting from off the walls of the Louvre in Paris, France, where he and his two co-conspirators had been hired to make protective glass for some of its most prestigious works of art. It was neither the most famous painting in its gallery, nor the most famous painting at the museum, nor even the most famous painting by the artist in question. But 24 hours later, when the theft was discovered, images of the painting were splashed across the front pages of newspapers all over the world. It had become an overnight sensation, with people even visiting the museum to gawk at the blank space on the wall where the piece once hung. A colourful array of theories and suspects were drawn up to try and solve the mystery of the theft. Following a two-year international manhunt that ensued to find the missing artwork, Peruggia was finally caught in Italy in 1913, with the now infamous painting returned to its rightful home. It had become the most recognisable piece of art in the world. It was now a household name known to people who knew nothing else about the art world.

Spoiler alert - that painting was the Mona Lisa. But without the story of the high profile theft, it would have been just another great painting from a great artist. It wouldn’t have become the Mona Lisa. Like many famous works of art, narrative aids like the background of the artist, the time period, the subject and the concept help to elevate the splotches of paint on canvas to something more than just its constituent materials. They become important historical artefacts that attain a monetary price that justifies their cultural significance (or vice versa). Like many aspects of human life, the value is determined by markets (and people) that understand how to attach the right number and the right meaning to the right story.

Bitcoin is the perfect example of the power of a good story. It has all the makings of a modern religion - a mysterious founder, a holy text, a legion of disciples, sacred rituals, ideological conflicts etc. In many ways it is the ultimate meme, because it is a meme about money, which in turn is one of humanity’s most cherished memes. More than any others, money is the meme that lubricates society. It is simultaneously a proxy for societal trust, and a placeholder for recording and transferring value. It is an ancient story about how value should move between people that has garnered social consensus over time. We’ve come a long way from commodity money (shells, animal skins, metals) to the government-backed (re: belief-oriented) fiat system we have now. Today the notes in your wallet are just pieces of paper that come with a government guarantee.

Bitcoin is just one idea of how money should work. Without a CEO, a President, or any kind of centralised direction or control, this idea has managed to capture the imagination of hundreds of millions of people from all over the world. These individuals have bestowed this system (and this asset) with a monetary value that crossed over $68,000 for a single bitcoin in November 2021. Despite the fact that this ‘currency’ hasn’t been issued by a sovereign government (like traditional fiat currencies), and despite the fact that it cannot boast typical cash flows (like corporate equities), the ‘market’ has enabled bitcoin to command a total capitalisation of almost $1 trillion. Its value is a product of pure belief in the idea of decentralised money i.e. bitcoin (the asset) has value because people believe that bitcoin (the idea) has value. That the technology works too is a bonus. If you think that’s silly, chalk that down to a failure of imagination.

As we’ve learned, human society is made up of tons of absurdities that are propped up by nothing more than memes and stories. Think about the narrative alchemy we’ve employed to create:

‘Ivy League Universities’ from a campus of teachers and buildings

‘Fortune 500 Brands’ from a collection of written contracts and logos

‘Billion dollar artworks’ from ink, oil and canvas

‘Sovereign nation states’ from essays (‘The Constitution’) and geography

‘Money’ from metals, paper and electronic data on a screen

In the last decade, we’ve discovered ways to continue the human tradition of collective fiction in a digital setting. Bitcoin demonstrated that fungible cryptographic tokens could indeed have value if we collectively decide that they should. But our lives are decidedly non-fungible. And our physical possessions mean more to us than we care to admit.

For instance, this is a picture of my actual backpack.

It isn’t aesthetically special. Its old. Its ripping at the seams. One of the zips is broken. It just about does what its supposed to do. Considering the manufacturer probably made hundreds of thousands just like it, I could probably buy a new one if I wanted. But this one was also given to me by KPMG on my first day of work when I was starting my career as a consultant in London in 2014. I’ve carried it on consulting assignments to different towns and cities across the UK. Its been with me on countless buses, trains and planes. Its been a constant even as I’ve moved jobs, titles and homes. So, no, come to think of it - I probably couldn’t get another one just like it.

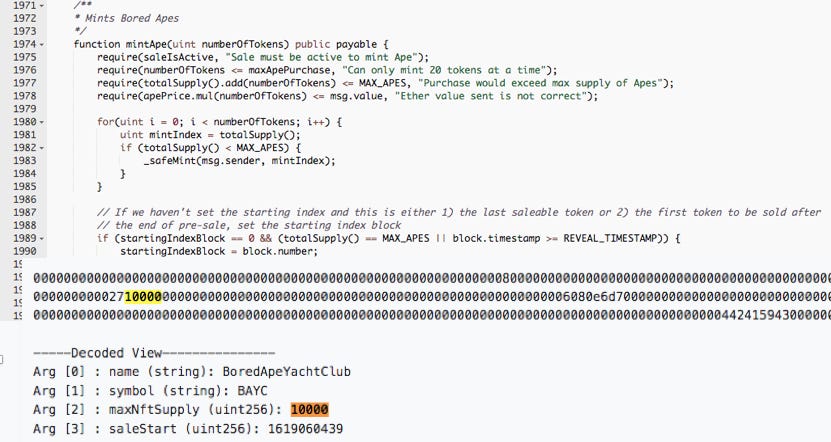

These are screenshots from the actual Bored Ape Yacht Club smart contract.

It is made up of characters in a programming language. It is a few lines of code that contain information like how many tokens are part of the collection, the rules around minting an individual NFT, guidelines for transferring ownership of each NFT, the ticker symbol of the token, details around where the actual JPEGs of each Ape are stored etc. What it doesn’t contain, however, is BAYC’s cultural footprint. It doesn’t contain any information about the social capital and status conferred on a BAYC NFT holder today. It doesn’t document the absurdity with which some (rational) observers regard the price of this asset. It doesn’t contain any of the intangibles that have made BAYC a cultural phenomenon. That’s the part we filled in.