Are We There Yet?📍

From paper to pixels and maps to markets - a two-part series on India's geospatial renaissance and "the most important policy change since liberalisation"

Hey folks👋

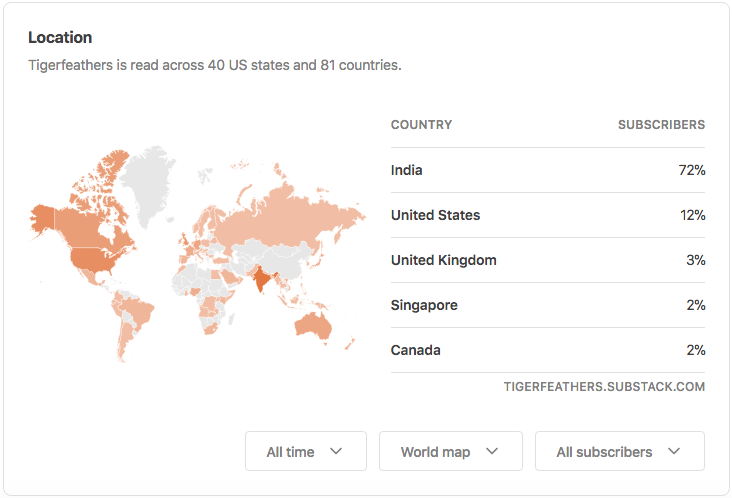

Welcome to the 351 new subscribers who’ve joined since the last time we did a roll call.

A few weeks ago we realised that in 81 countries around the world today you’d be able to find someone that subscribes to Tigerfeathers…

…which means that if everyone here was on board, we could basically start our own version of Club Mahindra if we wanted. Click here to book your first stay👇

Not to be dramatic, but it feels like today’s piece has been two years in the making.

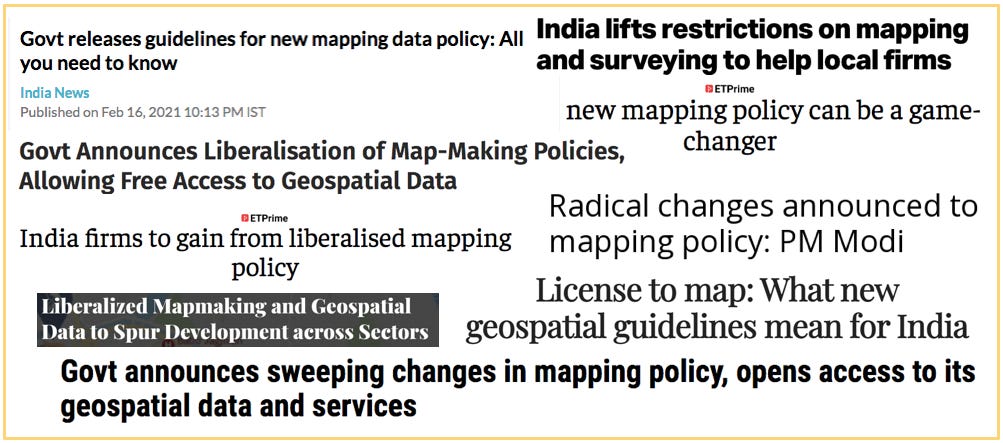

If, like me, you spend a decent chunk of your time scrolling through Indian startup Twitter, you might remember a couple of days in February 2021 when it felt like everyone on the timeline was suddenly excited about the same thing.

That ‘same thing’ was the Indian government’s decision to introduce a set of landmark policy changes on mapping and geospatial data. Among other things, it meant that Indian companies could:

- create and publish high-resolution digital maps

- access location-based data from sources that had been historically cordoned off

- innovate on the back of that data without the fear of flouting some arcane piece of legislation

The old mapping regime was a relic from colonial India. It contained a litany of onerous rules and regulations that typified the worst infractions of our License Raj. These directives had stunted the ability of Indian companies to develop sophisticated mapping capabilities, in the bargain handing an unfair advantage to foreign players like Google.

Depending on who you asked, this set of changes had either been 76 years or 256 years in the making. Either way it was long overdue.

Ok but is mapping really that important?

(Spoiler alert - Yes, it is).

But that’s a fair question. Two years ago I wondered the same thing…

…till I stumbled on an interview with Rakesh Verma, the founder and CEO of India’s oldest digital mapping company - MapMyIndia. Rakesh and his wife Rashi had co-founded MapMyIndia over 25 years ago, embarking on a painstaking mission to build a reliable digital map of India that would culminate with an IPO in December 2021. While commenting on the gravity of the new guidelines, he declared that:

“This is the most important policy change since liberalisation.”

At the time, to me, that seemed like a bold statement to make. It’s like if someone told me their favourite cuisine was Cambodian food. At the very least, I was intrigued. But more importantly, I was keen to validate that statement myself (who knows, maybe I’ve been missing out on Nom Banh Chok my whole life?).

Anyway, the deeper I dug, the more it seemed like ‘mapping in India’ was a topic worth understanding. For instance, did you know that 80% of all digital data has a geospatial (re: location-based) component? Or that better mapping could bring down our national logistics costs from 14% of GDP to 8% of GDP? Did you know that, at best, only 15% of India has even been properly mapped?? Or that poor addressing systems mean that last mile delivery costs are 3x more in India than they are in the US? I didn’t.

I also didn’t realise that having accurate geospatial data was critical to everything from urban planning, to forecasting crop yields, to avoiding a hangry brawl with your Swiggy delivery agent, to getting a mortgage in rural India, to finding an Uber home after a night out, to building good emergency response systems, and even to catching stray Pokemon lurking in the grass around you.

You might not realise it, but the smartphone age placed a digital map in each of our hands. In fact, many of the most potent social and economic changes that we typically attribute to having 24/7 access to a portable computer are really the consequence of having 24/7 access to portable digital maps that are updated in real time. The ‘smartphone’ age may as well be called the ‘digital mapping’ age. Think about it - every product from Hotstar to Amazon to Airbnb to Snapchat is counting on accurate time and location data to deliver their services effectively.

It means that our lives are now heavily dependent on the data, the software, and the applications that help us to accurately find our place in the world (I mean that literally, and not like in an existential way). And that’s before you consider all the other traditional ‘grown up’ industries like mining, logistics, transport, agriculture and real estate that depend on mapping to function smoothly.

Ok Ok…mapping seems kind of important. Why write this piece now though?

Because the mapping ‘guidelines’ from 2021 were crystallised into a formal National Geospatial Policy only in December of last year. And more importantly, even after all this time, no one had written the ‘Indian mapping’ piece that I wanted to read. I was looking for a single source of truth that covered:

the history of mapping in India (to contextualise the new policy guidelines)

the importance of mapping and geospatial data in the digital economy

the consequence of the new policy for investors, entrepreneurs, operators and consumers (illustrated well enough so even a five-year old could understand)

a case study on an Indian startup that brought the ‘mapping problem’ to life

So that’s what this piece is. Or to be more specific, this piece is Part 1, covering points 1, 2 and 3 from the list above. Part 2 comes out later in April, featuring the story of an Indian startup making waves in the enterprise mapping world….but we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

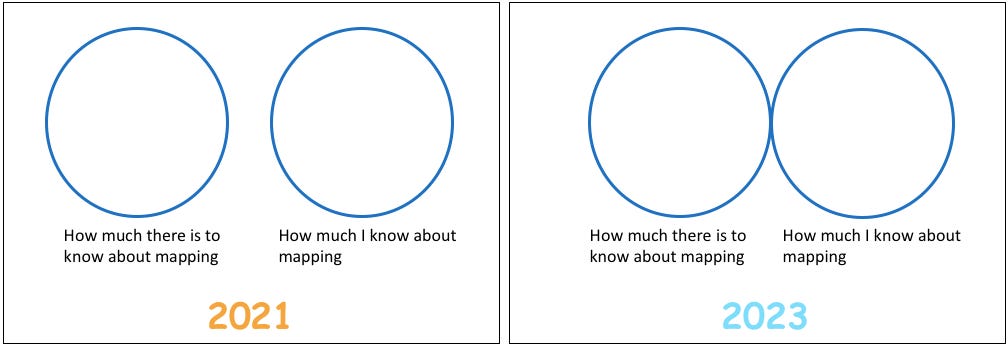

Anyway, the best part about tackling this topic was the fact that I could approach it with essentially a blank slate.

I’ve been able to spend the last 18 months speaking with founders, investors, lawyers and policymakers to get an understanding of this space from the ground up. I’ve taken full liberty to ask them stupid questions (like what the hell ‘geospatial’ actually means). If I’m being totally honest, last year I could barely even spell geospaceshell, but look at me now.

If you make it to the end of this piece, you will get a tour through one of the most interesting (and least explored) prairies in our tech landscape. You’ll see how the contours of our mapping policy are baked into the history of India itself. You will also hopefully understand why there was so much excitement about this policy change, and why I was keen to write about it. Because as it turns out, the benefits of geospatial innovation tend to ricochet into almost every other crevice of the economy.

But enough chit chat.

To kick things off, we begin with a little detour through London.

London? Like in the UK?

Yeah, London. Like in the UK.

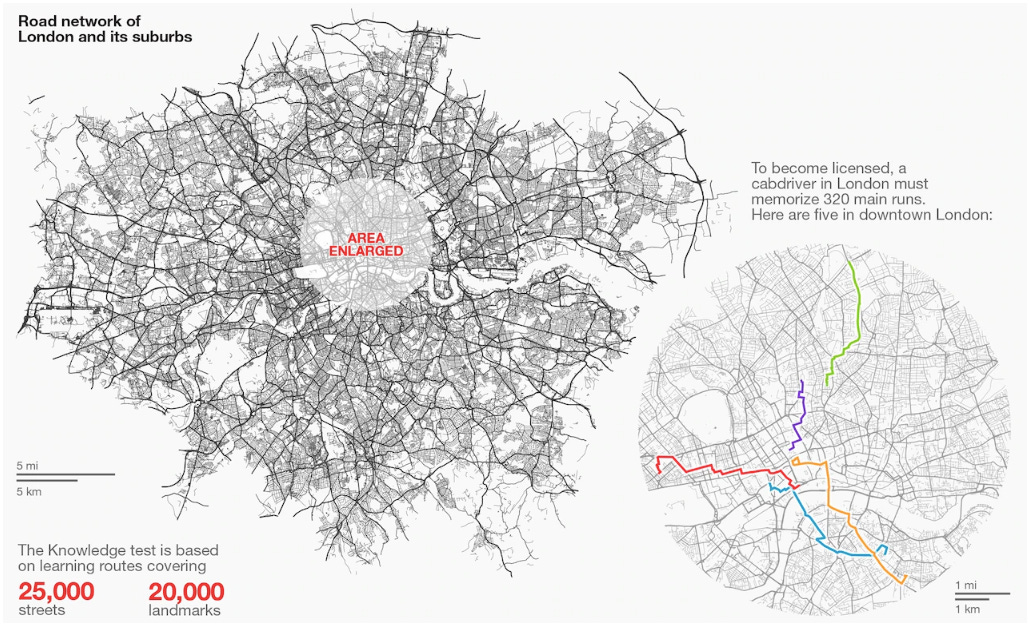

Did you know, that before they can get behind the wheel of one of the city’s iconic black cabs, aspiring London taxi drivers must complete a notoriously difficult series of exams to demonstrate their familiarity with the city. This series of exams is referred to as ‘The Knowledge’. It has been around since 1851, and is considered the most gruelling qualification of its kind anywhere in the world. The Knowledge is often hailed as an unparalleled test of human memorisation (outside of those offered by Indian school exams).

Hopeful drivers must memorise the names of 25000+ streets and 100000+ points of interest that are sprinkled across the city before they can obtain the prestigious ‘All London’ license that verifies their knowledge of the metropolis. They need to know every turn, every street, every landmark, every address, every route, and every alternate route that can possibly be taken in order to get from point A to point B. The difficulty is compounded by the fact that London has a freewheeling urban design that more resembles a forgotten ball of yarn than the manicured grids found in modern cities like New York, Shanghai, and even Chandigarh.

Over the course of 2-5 years, they must accumulate an encyclopaedic knowledge of the capital to help London’s residents and tourists navigate it without any technological assistance - essentially becoming the human equivalent of a GPS device. It’s said that only 1 in 5 candidates make the grade. Successful applicants earn the right to get behind the wheels of a black cab. It is a prestigious job that entitles them to flexible work hours and earnings between £45-100K per year.

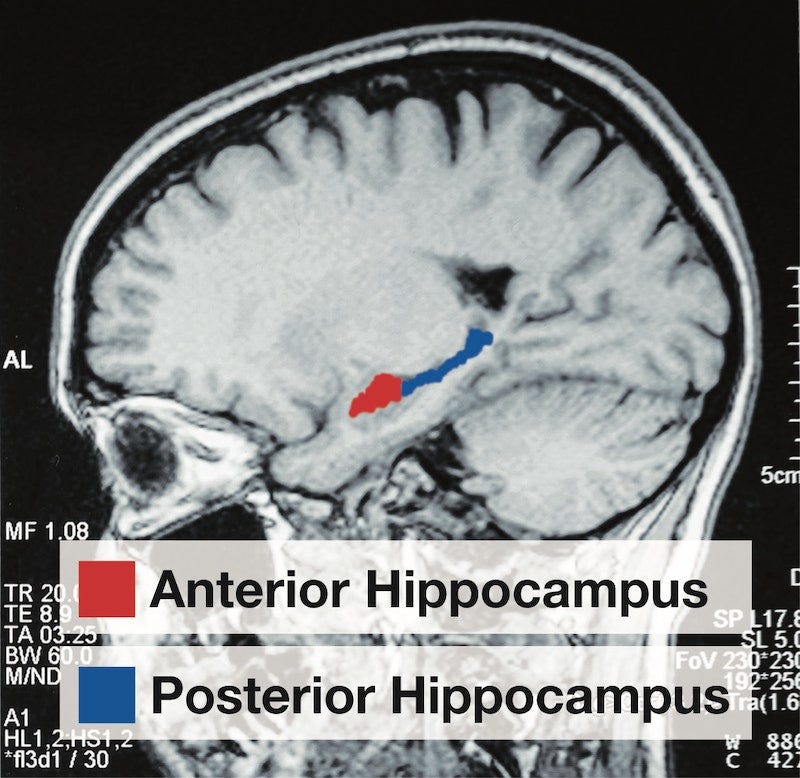

‘The Knowledge’ has become such a vaunted yardstick of cognitive prowess that in 2000, a group of researchers led by neuroscientist Eleanor Maguire decided to examine the effects of the test on the brains of successful drivers. It has become one of the most famous and oft-cited studies in the history of neuroscience. Researchers discovered that the brains of experienced London taxi drivers had a larger right posterior hippocampus than the left (re: the hippocampus is the part of the brain responsible for long-term memory and spatial awareness).

They also found that the longer someone worked as a taxi driver, the larger the volume of the brain responsible for memory. On the contrary, students that failed the test were found to have the same brain structure as a regular person. For reference, here is an MRI of my own hippocampus that I recorded last week:

The purpose of the study was to examine the ‘plasticity’ of the brain, to demonstrate that our brains can physically adapt to specific challenges we subject them to. In the case of ‘The Knowledge’, the challenge is navigation. By the time drivers had passed the test, the study concluded that they had established a ‘basic spatial representation of London’ in their brains. They were effectively walking around with a map of London in their heads.

Cool, so what?

In 2022, it can be hard to see that as being a desirable skill (‘Exhibit B’ of why they’ll never let me pass The Knowledge). In the 1900s and early 2000s, you had to rely on the navigational skills of your taxi driver to get from point A to point B. That ability was scarce, and thus inspired a fierce market for job seekers who could appropriately command a premium for their services. Today anyone with a smartphone has the same superpower.

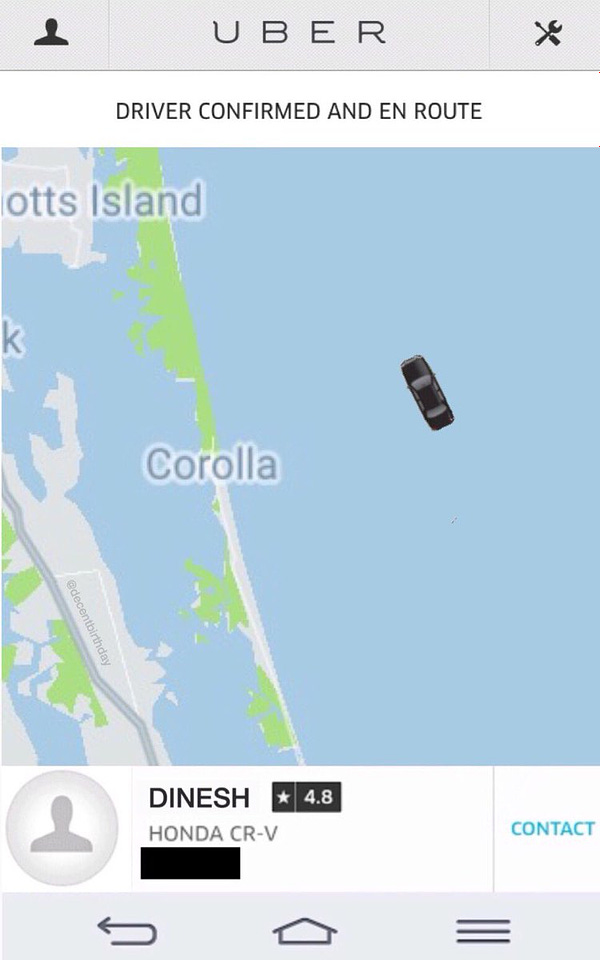

It isn’t a coincidence that the number of applications for The Knowledge has dropped by almost 95% over the last decade. Today everyone can access the knowledge from the palm of their hands. Amateur drivers can serve passengers in the guise of part-time professionals via their Uber and Ola apps. Ordinary citizens can optimise their commutes across cities using real-time information about traffic conditions, public transport schedules, accurate directions and ETAs for different modes of travel - all delivered via the magic of location services like Google Maps. The ability of black cab drivers to command a premium for their services has disappeared as navigational data has ceased to be scarce.

In just a decade and a half, we’ve forgotten the hassle of trying to manoeuver the world without our digital assistants - a time of finagling with paper maps, a time of asking kind strangers for directions, a time of hoping your taxi driver knew where you wanted to go and how to get to you.

You can think of the smartphone as the trojan horse responsible for smuggling a digital map into our everyday routines. But Google Maps was only launched as a mobile app in 2008. In-car navigation systems only became ubiquitous in India in the 2010s. The first satellite in our indigenous GPS system (NavIC) was sent into orbit as recently as 2013 (as a response to Pakistan-allied USA refusing to share GPS data with India during the Kargil War).

It’s hard to believe now, but we’re not that far removed from a time of geospatial blindness. (FYI ‘geospatial’ refers to information about objects and events on the surface of the earth. Geospatial data includes everything from satellite imagery, to the movement of a truck, to atmospheric weather conditions, to the statistics of crime in a particular area). It’s only in the last 40 years (and really the last 20) that location-based intelligence has become so commonplace.

Our modern digital maps are being constantly updated with high quality geospatial data from a number of different sources (like satellites, consumers, drones, mobile towers, wifi routers, street cameras, open source databases etc). This data is key to creating accurate maps that can be relied on for planning and decision making.

Today civilians, governments and enterprises can call upon a cupboard of navigational tools that help us make sense of our surroundings. These typically fit within a category called GIS (Geographic Information Systems).

Think about how many times a day you interact with a map to figure out where you are, what’s around you, where you need to go, and how you can get there.

Think about how many companies today depend on real-time digital maps to manage their logistics, complete their deliveries on time, find their customers, monitor their fields, plan their factory construction or their branch network.

Think of how vulnerable governments would be if they didn’t have a digital eye on their borders, or if they couldn’t react quickly to identify and contain natural disasters.

*Thinks*

It turns out, mapping is important, and not just to modern lifestyles and modern commerce, but to our geopolitical wellbeing as well. A digital map isn’t just a tool for navigation and search, its a way to straddle the divide between the physical and digital worlds.

It begs the question, then, as to why, for basically our entire history till 2021, geospatial innovation in India was trapped under bale of red tape. Mapping in India was regarded as a sacred practice, restricted to the domain of Central government priests, and especially taboo to private sector involvement. The collection and dissemination of geospatial data was severely restricted, subject to the worst ills of Indian bureaucracy. Indian companies were hamstrung by punitive regulations, leaving our mapping sector to be dominated by foreign giants.

With India making so many incredible strides in the 2010s, why was mapping left out of our digital metamorphosis? Why did it take so long to get our geospatial act together?

The answer to that question is incidentally also the answer to the question “why did you want to write this piece?” - Because the history of mapping in India is tied to the history of India itself. As Will Durant more eloquently put it - “Maps, like faces, are the signature of history.”

Intense.

Yes.

Alright I’m intrigued. Go on.

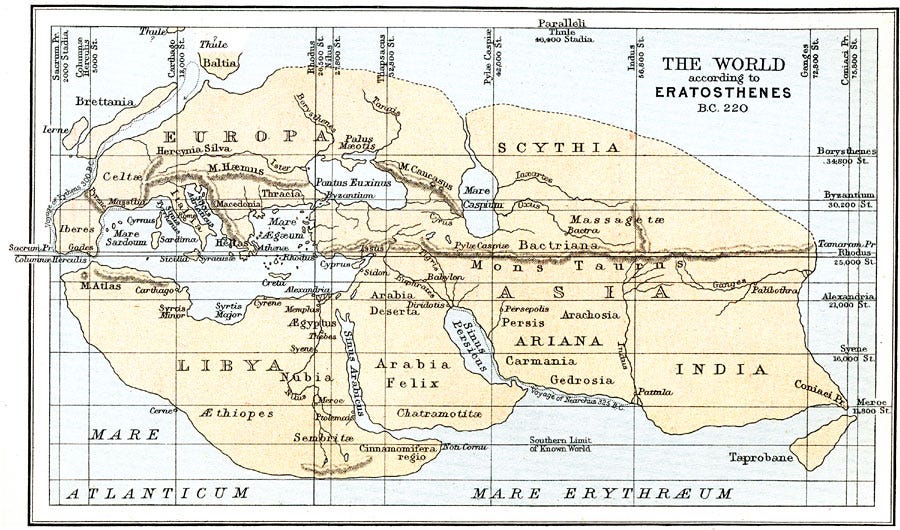

Our story begins in 220 BC…just kidding. I just needed an excuse to include this map of the world created by Eratosthenes, the Greek polymath and first person to accurately calculate the circumference of the Earth. His map is one of the earliest (and crudest) cartographical depictions of ancient India.

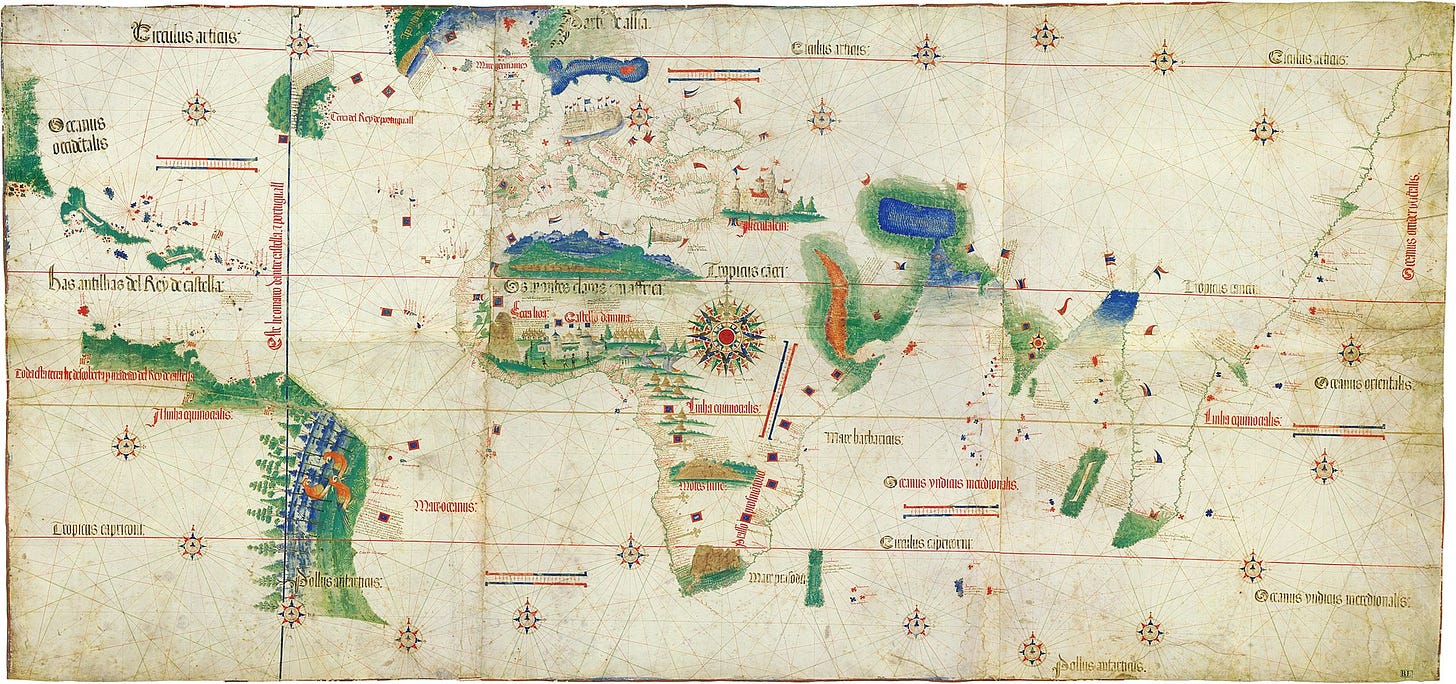

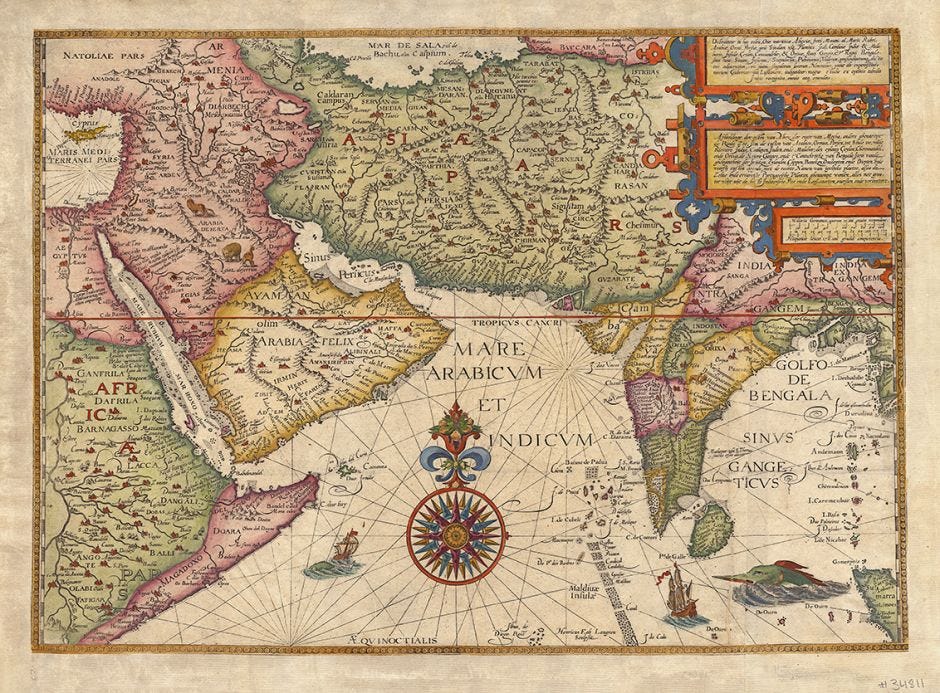

While resisting the temptation to do a historical exposé on Indian map making, it’s worth mentioning that most of the earliest known maps of India were made by Europeans during the Age of Discovery (between the 15th and 17th centuries). Back then, having a precise map meant having a keen knowledge of sea and land routes (gathered from experience), which translated to dominance over lucrative trade channels. Map making was shrouded in secrecy because it was often the difference between having an empire and an empty coffer.

The ‘transferring’ of geospatial information was largely the result of espionage, piracy (the original version), skulduggery, and maritime warfare.

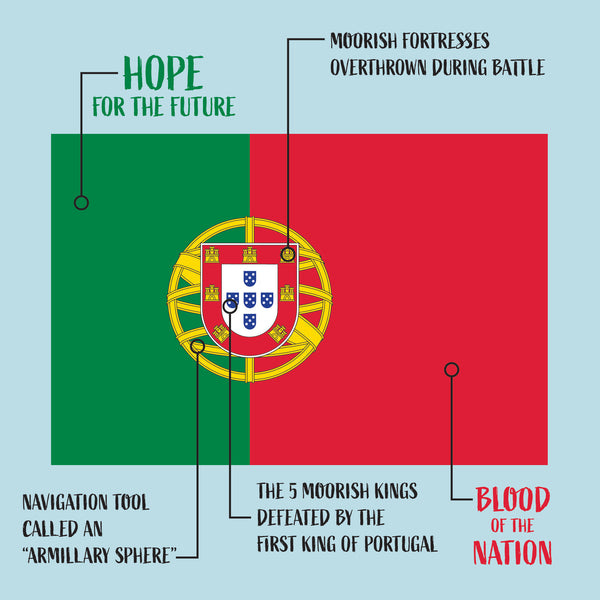

The Portuguese, because of their superior ships and map-making abilities, had won themselves a century-long head-start in India over their colonial rivals. They had become early pioneers of navigation technology (NavTech?). This was a necessity, partly to fuel their appetite for exploration, and partly because they needed to find an alternate trading route to the spice-laden East. The rise of the Ottoman empire in the Middle East had threatened the reliability of their traditional overland corridor (commonly referred to as the Silk Road).

By the end of the 1500s, however, the Portuguese monopoly in India had ended. Merchants from France, Holland, and Britain (via a new startup called the East India Company) had been alerted to the glittering pools of profit that were being generated from the import of spices like cinnamon, pepper and cardamom to Western markets.

Crucially, their hard-earned navigational intelligence was no longer a national secret. With each successive European voyage to the subcontinent, the rendering of India’s image on the world map became clearer.

The Dutch and the British in particular had been emboldened by the work of a Dutch innkeeper named Jan Huygen van Linschoten. Van Linschoten had spent five years as an assistant to the archbishop of Goa, a time where he managed to gather critical intel about Portugal’s activities in the region. On his return to the Netherlands in 1592, he published a seminal book called Itenarario about his adventures in India. In it he documented all his learnings about Indian culture and local life, along with several detailed maps of the region (like the one below) that finally illuminated the treacherous sea route to the mythical ‘East Indies’ around the Cape of Good Hope.

Once the other colonial powers realised there was a tried and tested passage to the East, it was effectively open season on the subcontinent. European trading companies lined up to set up stall in all the ancient ports of Surat, Cochin, Madras and Bengal, hoping to productively co-exist with reigning Mughal rulers (*ominous narrator voice* until conquest superseded diplomacy as the most reliable path to profits). Not only was India contributing 1/4th of the world’s GDP at the time, but it also quickly became the economic engine for the leading empires of the Western world.

So while the section above may or may not have been an excuse to showcase some cool maps of India, it also serves to emphasise the strategic importance of having up-to-date cartographical information even in the Middle Ages (especially in the Middle Ages).

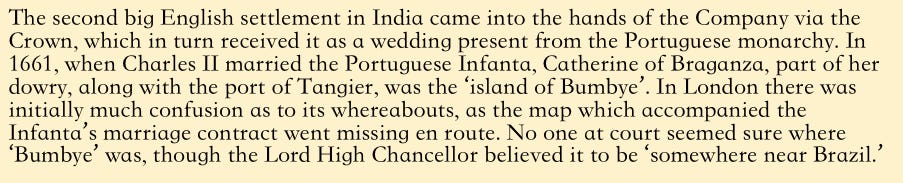

A good map could be the difference between Bombay and Brazil, as illustrated in the paragraph below from William Dalrymple’s The Anarchy, which recounts the confusion that surrounded the East India Company’s takeover of Bombay from the Portuguese:

Thanks for the history lesson (that no one asked for), what does this have to do with the mapping policy?

I’m getting there.

In the 1600s each of the major colonial powers had made themselves comfortable in India, settling into their respective corners of the Mughal-ruled subcontinent. Mimicking a trend started by the British, the individual French, Dutch and Portuguese trading activities were consolidated under the canopy of a joint stock corporation. They had their own versions of an ‘East India Company’ blessed by their respective national governments. Each became an economic appendage of their homeland, importing valuable spices and textiles from a resource-rich India.

The strategic imperative had changed from navigating to India, to navigating within India - i.e. from exploration to administration. That burden would ultimately fall on the British.

When the dust settled after the Battles of Plassey (1757) and Buxar (1764), the British East India Company (EIC) had seemingly outlasted a Royal Rumble of local and foreign challengers to become the dominant force in India. Through a mix of corporate ruthlessness, modern warfare, conspiratorial alliances and the decline of traditional dynasties, they had become “a state in the guise of the merchant.”

A state requires better cartographic tools than a profit-seeking corporation. The EIC now needed to have a precise understanding of the terrain in order to properly collect taxes, assign property, defend its territories, and plan large scale infrastructure projects.

“You can't use an old map to explore a new world” - Albert Einstein

So in 1767, the EIC created a central agency called the Survey of India (SoI). It was assigned the mammoth task of surveying and mapping the Indian subcontinent. Fun fact - the SoI was also bestowed with a de facto monopoly on map making in India, a hegemony it would retain for 256 years until a certain policy change introduced in February 2021…

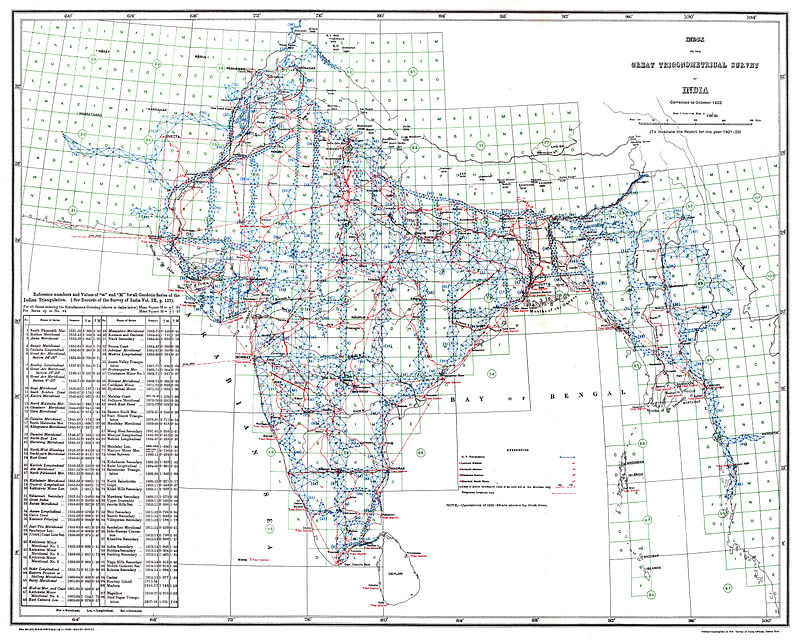

…but I digress. In any case, back then, incentivised by the urgent need to bring their newly acquired empire under control, the British developed mapping techniques that would place India at the forefront of geospatial innovation in the 1800s. Most notably in 1802, the SoI embarked on a 69-year long project called the Great Trigonometrical Survey that would become the “first modern scientific survey of India”.

Spearheaded by two Company surveyors, William Lambton and George Everest (the dude they named the mountain after), the EIC used a combination of man, machine, and math (🤷♂️) to create the first accurate graphical representation of India. Using remarkable foresight and technical nous, they took into account factors like the curvature of the Earth, the elevation of land, and the impact of gravity and temperature on their measuring equipment.

On the completion of the Great Trigonometrical Survey, we went from maps that looked like this:

To maps that looked like this:

Creating a detailed map of India was considered one of the greatest scientific achievements of that time period. It was also shrouded in controversy.

Why?

Sanjeev Sanyal, former Principal Economic Advisor to the Government of India, summed up the situation neatly, reasoning that:

“Because the British were carrying out much of the surveying for the purpose of actually being able to control a country that they had colonised, it also meant that they were very careful about sharing this information, because this obviously had a huge amount of defence and security usages. So…while the craft of cartography and map making remained largely in the private sector in Britain itself and in many other parts of Europe, in India it became a monopoly of the Survey of India.

Obviously the British were not very keen on sharing the information that they had…because this improved cartographic information was critical for their ability to first beat the French, but later on also beat the Marathas when they were conquering India”.

But the British eventually…left. Right? Wouldn’t our approach to map making have changed to reflect the requirements of an independent nation?

That would be reasonable to assume.

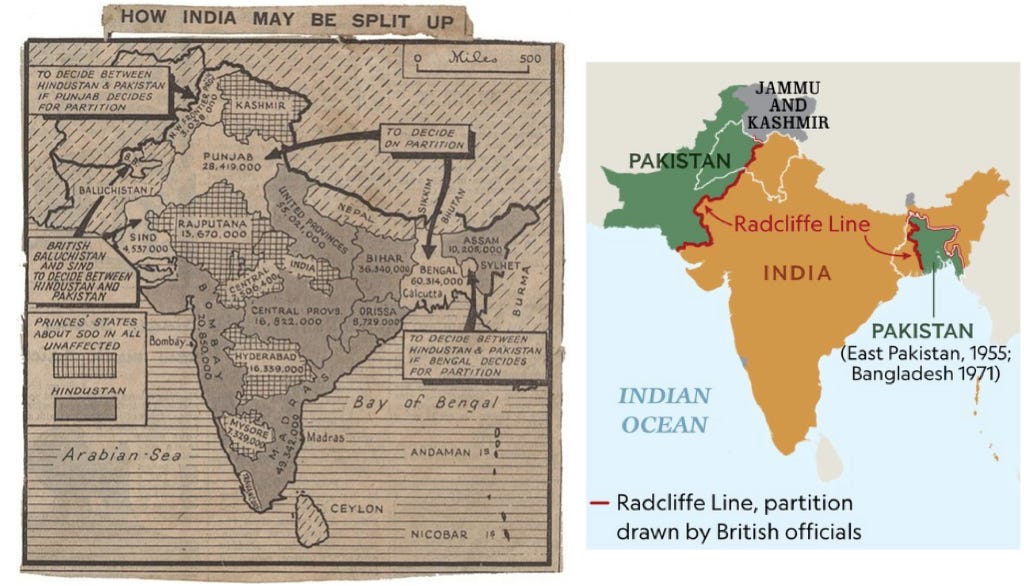

But post-Independence India inherited the same administrative paranoia and security concerns from its previous rulers. Ironically much of this was due to the carving up of the land mass into volatile chunks of territory, hastily orchestrated by a British lawyer named Cyril Radcliffe (who was given the quixotic task of partitioning India despite never having previously set foot on the subcontinent).

As it turned out, Independent India was still a minefield that needed to be navigated carefully without setting off any of the volatile components within and outside its freshly drawn borders. It made sense for our fledgling government to keep its precious knowledge of the terrain close to its chest.

“Serving in Afghanistan some 13 years ago, I learned of a historical local saying: ‘First come the hunters, then the surveyors, and finally the Army. So kill the surveyors’”

- John Kedar, writing for Geospatial World magazine

Our national leaders wasted no time in putting their fountain pens to work. The Survey of India Act (1948) anointed the SoI as the official survey and mapping agency of India. Among others, a new law - the Survey and Mapping Act (1952) - made it illegal for any individual or organisation besides the SoI to create, publish or distribute maps of India without permission from the government. It was amended in 1966 to include a prohibition on exporting maps and charts that depicted India's boundaries and territories. The Official Secrets Act (1923) was amended in 1951 to include geospatial data within the category of ‘official secrets’.

This conservative approach made sense in our initial post-Independence years when we found ourselves frequently mired in violent border skirmishes with the likes of Pakistan and China. To an extent, it even makes sense today when it comes to preventing inaccurate portrayals of India’s sovereign territory as per the official position of the Indian government.

But these laws were designed for an analogue world.

Maps of ancient India were often pictorial, created by individual travellers and explorers, drawing on astrology, cosmology, and even the descriptions of places in ancient texts like the puranas and the Ramayana. The Europeans upgraded this methodology to include sophisticated instruments and surveying techniques like ‘scale-bars’, compasses and theodolites.

But as you might expect, mapping in the modern age is very different.

I feel like I know why, but how about you tell me anyway?

I could, but this scene from Season 2 of White Lotus does a decent job too:

“Is everything boring?”

“Boring? No.”

“I just feel like there must have been a time when the world had more…you know, like, mystery or something…and now you come somewhere, like this, and its beautiful, and you take a picture, and then you realise that everybody’s taking that exact same picture from that exact same spot. You’ve just made some redundant content for stupid Instagram and you cant even get lost anymore cause you can just find yourself on Google Maps.”

“Throw away your phone.”

“Yeah.”

“Throw it in the ocean.”

Today, for better or worse, geospatial data is a public commodity.

We get vivid images of the Earth in real time from thousands of satellites owned by governments and private corporations that orbit the planet. We determine our live locations from Wifi routers, cell phone towers and GPS signals that are beamed from these satellites straight to our smartphones. The physical measurement of land has been replaced by aerial photography and street view cameras. Companies like Google and Apple have packaged complex geospatial data into consumer-friendly applications. There are even collaborative projects like OpenStreetMaps that have crowd-sourced publicly available maps of the world (more on this in Part 2).

Much of mapping has been eaten by 21st century software and hardware. Your phone has become your atlas, your compass, and your mariner’s wheel. Ordinary citizens now have access to precise geospatial information that would have (literally) fetched a king’s ransom in the colonial era.

So by the 80s and 90s (and certainly the 2000s and 2010s), the Survey of India was enjoying a hegemony over an activity that had been democratised around the world. They were tasked with protecting data that was outdated and now largely available in the public domain. The old rules had long outlived their expiration date.

From Sanjeev Sanyal again:

“In 1947, we became Independent. Now you would have thought that having become independent we would take a different view of the Survey of India and its monopoly. Sadly that is not what happened. Much of the earlier thinking around security and close control of cartographic information flowed through even into the subsequent decades.

Perhaps in the initial decades it may have made some sense, but certainly since the 80s and 90s much of this information was freely available through satellite photography to any of our geopolitical rivals, and in fact by the 2000s we were even able to get some of this information directly off Google. So this monopoly over time, became largely irrelevant. Worse, this began to get in the way of private innovation in the sector.”

So that’s why our mapping policy needed upgrading?

“You can’t use an old map to see a new land” - Gary Hamel

If you look at the history of tech innovation, you will often find that progress is a function of both better technology and pragmatic regulation. Writing in her seminal book ‘Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital’, Carlota Perez argued that:

"In the deployment phase [of new technology], a great deal of investment goes into the complementary infrastructure, the standardization process and the new legal and institutional arrangements necessary for the new technology to be properly utilized. It is therefore the regulations and government policies that actively support or obstruct the path of a new technology, determining its adoption rate and its social and economic impact."

Granted, its not the most riveting piece of writing. However, it illustrates a useful point in our case. By the 2000s, technology had caught up to the demands of modern map makers and map users in India. Regulation, on the other hand, was a few decades (if not centuries) behind.

For instance - did you know that Google Maps (as we know it today) is largely a product of Indian ingenuity? Back in the early 2000s, Lalitesh Katragadda was the head of Google India. When Google Maps was launched in 2005, its utility was severely limited in countries with restricted access to geospatial data. He recalled how:

"Maps are very essential for the development of a country. It didn’t quite make sense to me until I read a book by Hernando de Soto, who talked about maps and property rights, and them being responsible for a country's progress. When I came to India with zero knowledge of my neighbourhood and routes, I knew I needed a map. I drove a GPS truck to map the roads, which cost $10-$15 per kilometre. India had 3 million kilometres and $45 million wasn't a possibility. Even if we approached tech giants like Yahoo, there wasn't any substantial Return of Investment for this idea. Since the roads keep changing every five years, spending 45 million dollars every five years isn't something India could afford."

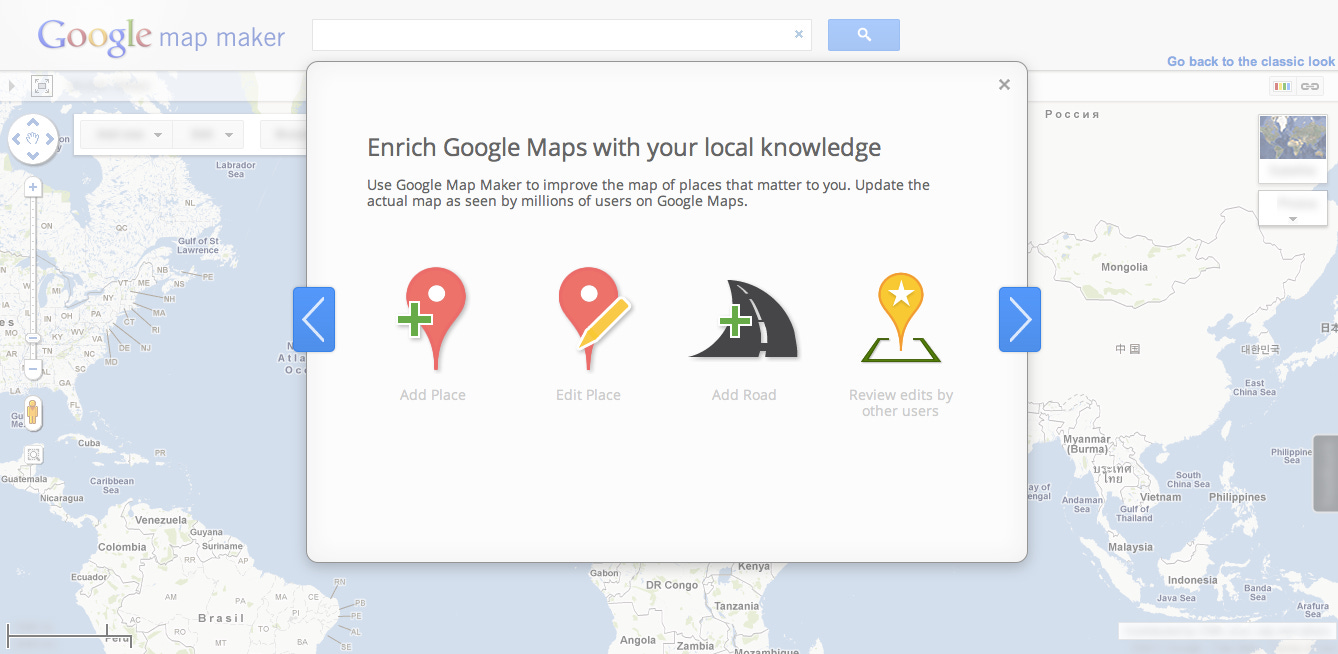

To solve the twin challenges of expensive data gathering and a lack of access to geospatial data from entities other than the Survey of India, he and other visionaries like Sanjay Jain and Manik Gupta conceptualised a product called Google Map Maker (GMM). GMM was an editing tool that allowed ordinary citizens to make edits to Google Maps, adding useful information about local schools, roads, hospitals, businesses etc that would enrich their communities.

“I like to think of the map as a planet-scale canvas which is highly interconnected which people are editing” - Lalitesh Katragadda

New edits from reputed users were visible on the map almost immediately, and could be peer-reviewed for accuracy by other community members. Impressively, 97% of these contributions were considered authentic, validating the decision to trust and empower ordinary citizens to accurately map their surroundings. Map Maker was a runaway success. It became “the first large internet product to be launched in the Eastern hemisphere, and then moved to the Western hemisphere”.

The tool was eventually rolled out in 186 countries, helping Google to tap into the intelligence of local communities to bolster their eponymous Map of the world.

Ah, so you could do interesting mapping stuff in India?

Yes, but you could also go to jail trying.

Come again?

The irony was, that despite Map Maker being incubated in India courtesy of the unparalleled jugaad of Indian engineers, in reality it was in violation of the prevailing mapping laws. Translation - it was illegal to do what Google did. That was because in 2005, in the same year that Google Maps was launched, India introduced a draconian piece of legislation called the National Map Policy (2005).

The National Map Policy (NMP) was a worthy successor in the lineage of punitive geospatial policy making in India. It was a throwback to the worst ills of India’s License Raj, introducing an Olympic track of permissions, licenses and hoops that needed to be jumped through for individuals and companies that wanted to engage in map making. It also prescribed restrictions for mapping around sensitive areas such as border regions, defence installations, and nuclear facilities.

Despite its goal of kickstarting the process of national geospatial capacity-building, it condemned Indian organisations (public and private alike) to another era of confusion with regards to the rules around map making in the country.

The main purpose of the NMP was to establish a set of standards and operational practices for private map making. For instance, private companies could now officially request access to mapping data from the Survey of India, but they needed to apply for a separate license if they planned on editing these maps or performing any kind of ‘value addition’ for commercial activity. The amount you paid for the license was proportional to the number of improvements you wanted to make (because these maps of India were considered a copyright of the SoI).

In theory, there was a logic to these stipulations. But in reality, it was time consuming, extractive, and practically impossible to comply with all the requirements of the NMP.

So how did Google do it?

Well, they didn’t.

In Google’s case, complying with the NMP was simply out of the question. There was no way they could request or wait for approval from the government for every edit made by an Indian citizen via Map Maker. They were risking further ire by using satellite imagery and third party map data without the government’s permission. The company was also flouting a provision from 1966 that prohibited the export of physical maps, because, by the semantic interpretation of the law, they were ‘exporting’ this mapping data to their servers and APIs. Not to mention, they had also secretly mapped 30 cities in the country for the first iteration of Google Maps India.

“It was an unfair situation earlier. Google Earth showed satellite imagery but Indian companies weren’t allowed. We had the tech before Google back in 2004. But we weren’t allowed to put out imagery while foreign companies could. In addition, for every small update, for even a pothole, we had to go and seek permission from the government that could result in a waiting period lasting days. With this, the government has righted a lot of wrongs”

- Rohan Verma (CEO - MapMyIndia)

At best, Google Maps existed in a legal grey zone. At worst, it was considered contraband.

To understand the status quo at the time, I spoke with Rahul Matthan, who is currently a partner at Trilegal and has been one of the foremost champions of India’s geospatial liberalisation since the early 2000s. He recalled that:

“The Indian government and the Ministry of Defence held a view that maps were a strategic geopolitical asset. Their position was influenced heavily by the Cold War, where the US and Russia kept their maps as closely guarded secrets. There were many stories about Russian spies embedded in the US that would send hand drawn maps of D.C. back to their homeland. That’s why India always believed that map making should be the exclusive domain of the state.

Pre-2000s it made sense for the SoI to keep our mapping methodology under wraps. The Trigonometrical Survey had helped us calculate the curvature of the Earth, which was a key piece of geospatial data. For example, this variable came into play when accurately targeting a missile strike (a real concern in the post-Partition years).

The problem was that by the 2000s, the Survey of India maps were no longer useful. No one used their raw mapping data anymore. Satellites and GPS systems had helped us calculate the centre of the Earth, which was a more precise reference point with regards to measuring time and distance on the surface. Our old methodology was obsolete.

Private companies had recognised the need for better mapping - for things like navigation services, oil mining, disaster relief and infrastructure planning. Some foreign companies like TeleAtlas and TomTom, and Indian companies like MapMyIndia, did things the old fashioned way by waiting for approval from the Department of Defence before they undertook any surveying or publishing of maps. The poor MoD representative was inundated with reels and reels of approvals and edits that no human would have been able to manage in a timely manner. That’s why private players often had to wait 6-9 months to get permission for any mapping activity or get access to any government mapping data. Despite this, these companies tried their best to obey the law.

Google, on the other hand, was a Silicon Valley upstart. They were used to moving fast and breaking things. Their legal teams had flagged the risks inherent in launching Maps (and Map Maker) in India, but they went ahead with it anyway.

As it turned out, Google deemed mapping important enough to risk the ire of the Indian government (which they had to bear the brunt of on numerous occasions). They had experienced firsthand how properly mapped roads and sites could be the difference between life and death when it came to things like disaster relief and disease management. They had seen local communities flourish and local commerce erupt as a consequence of accurately mapped neighbourhoods.

They were also really the only company with the resources to battle the government in court. Similar to many parts of the economy still shaking off the hangover from our socialist past, this was considered the price of doing business in India (a price not many entities could pay).

After several other attempts at crafting a sensible geospatial policy had met with false starts, by the end of the 2010s both the public and private sector in India had recognised that we had a problem.

Not only had we stifled private geospatial innovation, but we had de facto placed the keys to our mapping supremacy in the hands of a single foreign company. We had also failed to unleash the full potential of geospatial data in our digital economy - something that was crucial in areas like fintech, healthcare and hyperlocal services. This led to downstream suffocation of other parts of our startup landscape like drones, space-tech, and logistics-tech. Worse still, many of the concerns around geospatial privacy were moot, considering that anyone could now access detailed digital maps of India from a number of global providers using public data sources.

Anyone could see that it was time for a change.

Ok can you finally tell us about what happened in 2021?

Jeez I thought you’d never ask.

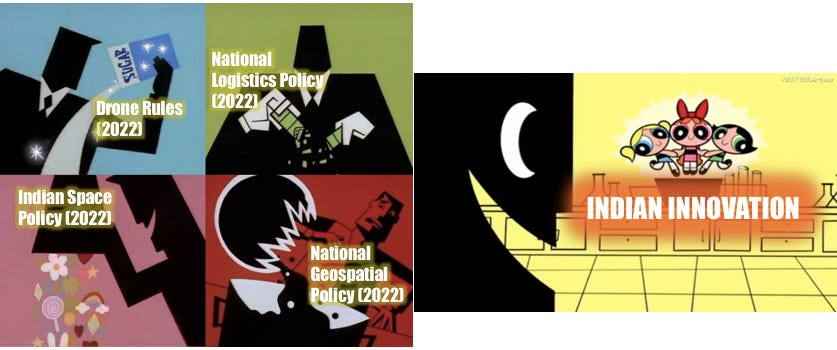

On 15th February 2021, the Government of India announced a long-awaited series of Guidelines that broadly aimed to liberalise our geospatial sector. These “sweeping changes” were intended to hoist our antiquated mapping regime into the modern age. The main objective was to wipe the slate clean for Indian companies, giving them the impetus to innovate without the fear of bureaucratic backlash.

Without wading too deep into technical legalese, the new guidelines stipulated that:

Mapping would be completely deregulated and liberalised in India. Any public or private entity could now collect, generate, process, or publish geospatial data (including maps) without needing to wait for prior approval, permission or security clearance from any government body

Any geospatial data produced using public funds would be made easily accessible to any Indian without any restrictions on its use (aside from classified information collected by security and law enforcement agencies)

Any Indian territory that was physically accessible could be mapped by Indian entities (before the policy change almost 46% of India’s territory was inaccessible without permission). Restrictions would now be placed on mapping attributes as opposed to physical boundaries (eg: the labelling or identifying of a sensitive location as an Indian army base)

Only Indian entities could legally collect data or create maps beyond a certain depth or accuracy (less than 1m horizontally and 3m vertically). Foreign companies that required high resolution geospatial data could only obtain it via license from an Indian entity. Any mapping products they made using this data could only be used and (the data) stored in India itself

Indian companies would be trusted to self-certify and apply good judgement with regards to adhering to the guidelines

But wait, there’s more.

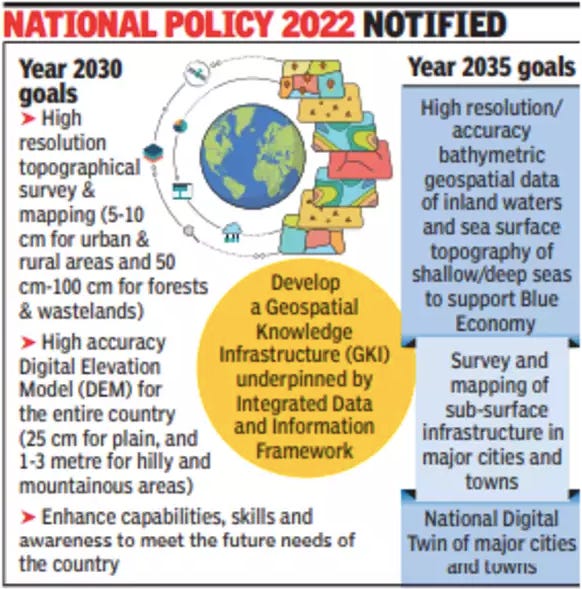

The 2021 Guidelines have now been crystallised into a National Geospatial Policy (2022) that was formally notified by the Ministry of Science and Technology on 28th December of last year.

Besides including the provisions from the original Guidelines, the new Policy presented a full-throated proclamation of our geospatial ambitions. It laid out the roadmap for a 13-year mission to establish India as a mapping superpower on the global stage. It left no doubt that the Central Government sees the unleashing of our geospatial sector as a formidable engine of progress, crucial to driving India towards the promised land as a ‘self-reliant’ $5 trillion economy.

Some of the major milestones outlined in the policy include the creation of:

- a legal and policy framework to liberalise the geospatial sector and improve access to location-based data for commercial enterprises by 2025

- a high-resolution topographical map of every inch of the country by 2030

- a revamped ‘data supply chain’ to streamline the process of sharing geospatial data between public and private entities by 2030

- a high-resolution geospatial survey of our seas and inland water bodies, with a view to nurturing our ‘Blue Economy’ by 2035

- a ‘Digital Twin’ of major towns and cities by 2035

All of that sounds good, but what does all this policy stuff mean for entrepreneurs, investors and operators in India?

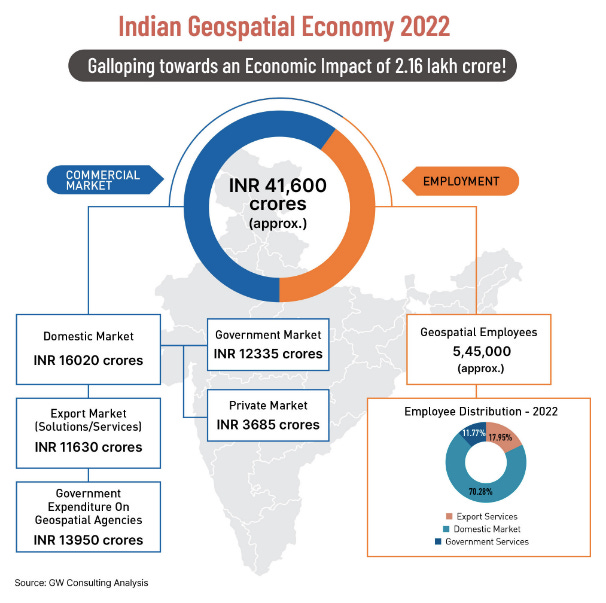

In his address to the second United Nations World Geospatial Information Congress (UN-WGIC) that was hosted by India last October, our Union Minister of State for Science and Technology, Jitendra Singh, declared that India’s geospatial economy was likely to surpass ₹63,000 crores by 2025, growing at a rate of 12.8%, and employing more than 10 lakh people, the majority of whom would be employed by geospatial startups in the country. He also estimated that there were around 250 geospatial startups in the country already.

Whether you choose EIC-India, colonial-India, or post Independence-India as your starting point, our geospatial sector has never been as ripe for opportunity and innovation than it is now.

So, if the previous section was too technical or too jargon-y for you, here’s the rub:

The GoI estimates that our geospatial economy will be worth “one lakh crore rupees” by 2030 (per the Ministry of Science and Technology)

It foresees the bulk of this value to be generated and captured by startups and private sector participants

It hopes to spark private sector innovation by easing the process of acquiring, accessing and sharing geospatial data within and outside the government

It has committed to streamlining the process of government procurement of mapping solutions/geospatial data, priming the market for private companies

Startups that previously had to wait months (and even years) for access to government datasets, for licenses to conduct mapping, or permission to experiment with geospatial technologies, can now do so freely

By sweeping up the red tape that had littered our geospatial industry, the GoI wants to open the door to new ideas, businesses, and partnerships between public and private players (that had so far been limited to only the most masochistic of Indian entrepreneurs)

To add some colour to the points above, Arpit Shah (Partner - Mapmyops), wrote at the time about the practical effects of the changing status quo, commenting that:

“The vision of the current government pertaining to the mapping sector, as captured in these reforms, is appreciable for two reasons - a) it opens up avenues for the creation of high quality geo-data of Indian territory and b) the benefits of these reforms accrue to those who store (and display) geo-data within India.

To procure satellite imagery, one needs to align and submit a request with the NRSC (National Remote Sensing Centre) - direct purchases from satellite companies is not possible. Often there is a lag of months between placing a request and receiving imagery. PoI datasets (Point of Interest) can only be created by the resourceful and obtained by those with deep pockets. Believe it or not, high quality PoI dataset of Delhi will set you back by half a crore rupees! These datasets are very useful for doing geo-analysis of any kind.

In comparison, the mapping / geo sector in other major economies is deregulated. Quality geo-data is captured, modified and disseminated by the government and private players. For example, in USA, geo-data as granular as household level ownership of selfie sticks is captured and publicly available. This means that, if one wanted to, one could draw a correlation between ownership of selfie sticks in a neighbourhood to its inclination to vote for a particular political party.

In India, one has to often only rely on the 10-yearly census geo-data to do household level geo-analysis of any kind. The next census is due this year which means if I were to do any socio-economic analysis using publicly available geo-data today, I would be compelled to use the outdated 2011 results for my study.

The new reforms, thus, gives an impetus to Indian organizations to create / update geo-data whenever they want to and disseminate it without too many levels of approvals at a transparent price to those who need it”.

Most of all, through the various guidelines and policies we’ve covered above, the key change has been the reconstitution of mapping in a new avatar - from being seen as a weapon of security and privacy to now being recast as an instrument of economic and social development. It’s not just about being able to make prettier maps of India, its about what you can do with better quality geospatial data, and how that will enrich different parts of our economy further downstream.

For instance, a liberalised geospatial regime is key to:

reducing logistics costs for hyperlocal delivery and e-commerce through more precise urban mapping and route planning

helping people in remote parts of India to secure their land titles and safeguard their property rights, allowing them to access formal credit, crop insurance, government welfare schemes etc. (For comparison’s sake, Lalitesh Katragadda estimates that we can unlock $4.5 trillion of capital through the mortgaging of land if the new policy is implemented properly, given that in India only 3% of all land has been capitalised vs 40% for all residential, commercial and government land in the US)

catalysing private participation in our space sector by letting startups play a role in the acquiring and processing of geospatial data

helping India manage the effects of climate change, by monitoring granular changes in atmospheric conditions, soil health, sea levels, water tables etc, thereby nudging us towards a more sustainable utilisation of our natural resources

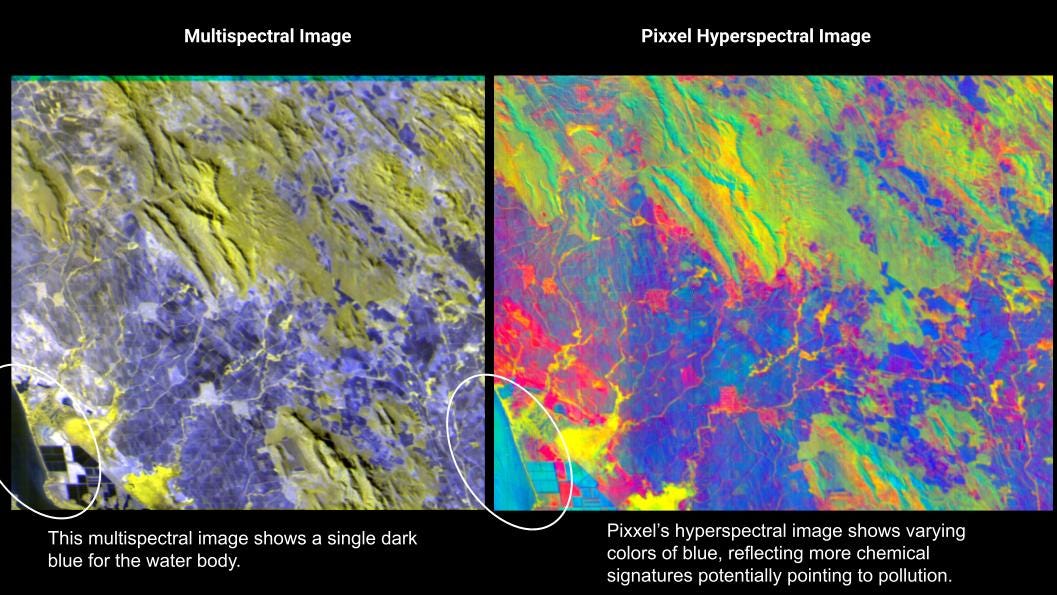

building high-precision, high-resolution, hyper-spectral maps that are pivotal for frontier sectors like electric vehicles (to plan charging stations), autonomous vehicles (better maps = reliable routing), Augmented Reality (to accurately overlay computer generated content on your surroundings) and renewable energy (to plan grids and suitable facilities)

unlocking the potential of our drone sector by allowing companies and government bodies to capture high-resolution images of agricultural land, mines, coastlines etc using drones, and deriving commercial intelligence from this data

Again, all of that sounds good, but what are people actually doing in this space? Have we seen evidence of the new policy in action?

The short answer - yes. Also, I don’t know if I really like your tone.

Sorry.

Whatever. Anyway, there’s plenty of evidence to suggest that Indian companies have heard the geospatial starting-gun loud and clear. So far, if I had to sort the various pools of activity into different themes (or buckets), this is how I would do it:

Some of the most interesting examples and demonstrations I’ve found, include:

Indore-based startup Pataa, that’s built a mobile app to solve the navigation problems arising as a result of India’s antiquated and unstructured address system. Their product allows consumers to create custom ‘short code’ addresses on a map. These codes can be shared with various apps and services (like Uber, Swiggy, Amazon etc) to give them a more precise way of locating their customers (i.e. so you can avoid constantly arguing with delivery agents and drivers when they can’t find your location on Google Maps). They claim that poor addressing causes ‘a substantial economic burden of $10 to $14 Bn to India annually’.

Indian startups like Pixxel and GalaxEye that are building proprietary satellites to capture richer geospatial data for various use cases. Pixxel wants to build a ‘health monitor’ for the planet, using hyperspectral imaging to ‘unearth underlying, unseen problems, that are invisible to satellites in orbit today’. GalaxEye is gearing up to launch a constellation of ‘multi-sensor’ satellites that can capture and analyse atmospheric data without the limitations of traditional single-sensor satellites. Both companies have ambitions to impact the lives of people and organisations far beyond India’s borders.

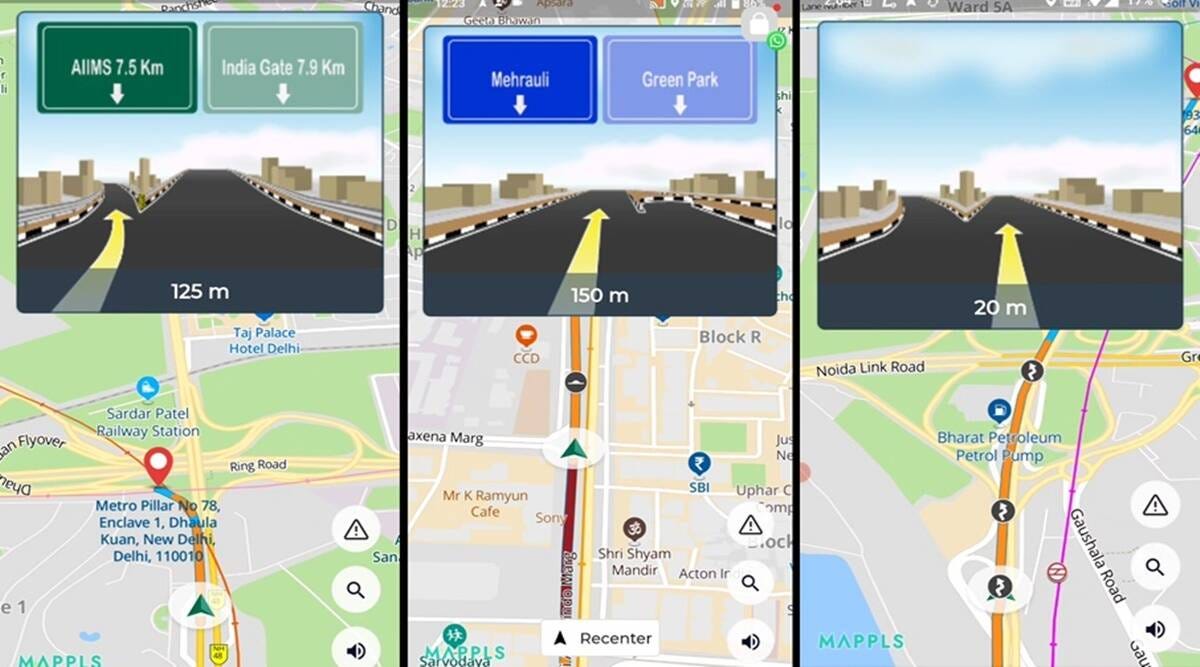

MapMyIndia partnering with the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) to use the latter’s satellite imagery to build indigenous mapping and navigation solutions that can compete with Google Maps and other foreign providers. They are confident that ISRO’s rich geospatial datasets will help them build products that are more precise and in-sync with local realities than any foreign competitor (“We know India better than everyone” - Rakesh Verma, Chairman and co-founder of MapMyIndia).

I’m going slightly off-course here, but MMI should be recognised as one of the greatest testaments to Indian entrepreneurship we have today. Over 25 years they’ve physically mapped 98.5% of India’s road network and 7.5 lakh villages (giving them an edge over Google in rural India). They stepped up to the plate during the pandemic, integrating with government portals to help plot all the COVID vaccination centres in the country. And they recently even published a series of geographically accurate maps depicting Ram’s journey in the Ramayana, leveraging their suite of proprietary tools and techniques. Straight legends.

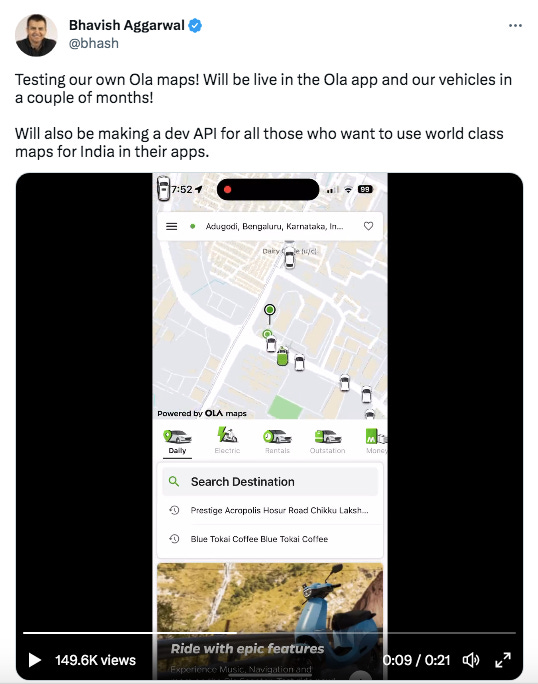

Even companies not traditionally in the ‘geospatial’ sector, like Ola, are throwing their hat in the ring to build a better indigenous map of India using their hard-earned geospatial intelligence.

Google, on the other hand, had to partner with Tech Mahindra and Genesys International last year to license satellite imagery from the two companies for its Street View services in India. Google is prohibited from collecting, storing or owning street view data itself per the stipulation of the 2021 Guidelines.

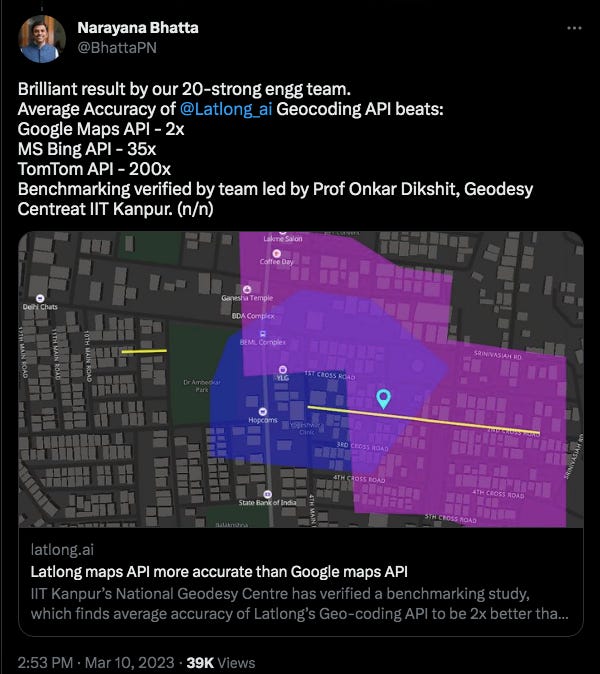

Most recently, a Bangalore-based startup called LatLong made waves when it proved that its new ‘geocoding API’ was 2x better than even Google Maps (and significantly better than other leading global map providers). Their secret sauce was the incorporation of geospatial datasets based on local languages (courtesy of AI4Bharat) to improve the precision of addresses on their map.

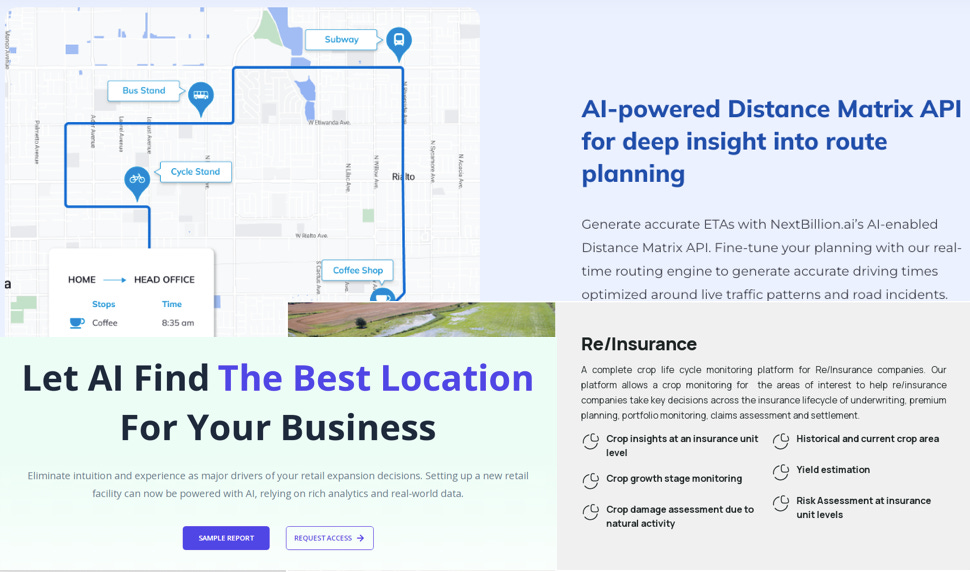

A mix of traditional enterprises (eg: Satsure, Genesys, ESRI India) and younger startups (eg: NextBillion.ai, GeoIQ, GeoSpoc, Locus, Heliware, Data Sutram) using geospatial data from a number of public and private sources to provide location-based intelligence for governments and enterprises - to help them with things like market sizing, supply chain planning, route optimisation, traffic management, borrower risk profiling, maritime surveillance, utilities fault detection etc. There is an argument that in 2023 a lot of ‘basic’ digital mapmaking has already been commoditised. But when you take into account that Indian companies now have exclusive rights to collect high resolution terrestrial and maritime data within Indian territories, and the fact that we’re entering a brave new world for AI, it means we’ve barely scratched the surface of the transformative economic and social effects of Big (Geospatial) Data.

To temper any accusations of hyperbole, I’m contractually obligated to add a note here to stress that these changes won’t be felt overnight. This is a long term vision (13 years to be precise) rather than a quick fix. It will take time for everyone to get on the same page. There will be growing pains as government departments adjust to the new standard operating procedures. Industry participants highlighted that there still needs to be considerable training and capacity building to equip public officials with the ability to cater to all of the demands from the private sector. There are some who foresee a muted change rather than a big bang, arguing that the government has always been harsher at setting geospatial rules rather than enforcing them. Critics have even argued that privacy issues and national data security concerns still need to be addressed in the rollout of the policy…

…but, despite everything I just said in the paragraph above, to people who have been paying attention to this sector for a while, its clear that India now has a chance to reclaim its position as the epicentre of geospatial innovation in the world - a distinction we held throughout the 19th century.

To anyone who hasn’t been down the geospatial rabbit hole yet, to investors and entrepreneurs and the generally curious in India, I hope this piece can be a welcome mat to the world of mapping. And if you do decide to go further in, please get in touch. I’d love to learn more about what you’re building.

👏👏…what now?

Now we wrap this up.

Like I said up top, it feels like this piece has been in my head for two years. Right from the day the original guidelines were published, it felt like mapping was a corner of our startup ecosystem that merited a visit. I didn’t realise that even in the digital world success can really come down to location, location, location.

Lately, often my first thoughts when I look at an app or website are “I wonder how location plays into their operations?”, “I wonder what mapping service they use?”, “Could location data help them to materially reduce their costs or improve their bottom line?”, “Are they using geospatial intelligence to find an edge?”, “Could they??” etc etc.

In the process of my research, I was curious if companies had fully grasped the potential of geospatial intelligence to improve their operations (i.e. was enterprise mapping even a thing)? Or better yet, had they realised that mapping could be a strategic asset if done right? And was there an Indian startup positioning themselves to be the mapping sherpa for public and private companies?

That’s where NextBillion.ai comes in. It is a three-year old startup that’s helping enterprises build their own custom digital mapping solutions (I promise I’ll explain what that means in Part 2).

It was started by Ajay Bulusu, Gaurav Bubna, and Shaolin Zheng in early 2020. The trio were founding pillars in the mapping team at Grab, where they learnt firsthand how crucial mapping was to the unit economics and consumer experience of modern digital products.

They’ve been on the enterprise mapping train since well before it was cool. Their background and their products present a neat case study on how geospatial intelligence can be an instrument of leverage for companies in the digital age.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves again.

For now, take a breather. We’ll see you next time around for Part 2.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A big thank you to Rahul Matthan (Trilegal), Bhavik Merchant (SWANSAT), Saahil Deo (Zepto), Dhruv Jhaveri (Freight Tiger), Ashish Dave (Mirae Asset VC), Ajay Bulusu and Gaurav Bubna (NextBillion.ai) for taking the time out to chat with me and share their insights. I would be remiss if I also didn’t mention Rakesh and Rashi Verma from MapMyIndia; and Lalitesh Katragadda and Sanjay Jain, who, along with other tireless iSpirt volunteers like Rahul Matthan, have spent decades trying to overturn India’s draconian mapping regulations. The Indian geospatial sector owes much to their persistence and foresight.

If you made it all the way here and you thought this was a good use of your time, it would mean a lot to us if you took a couple of seconds to share this post.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rahul Sanghi most recently served as Fintech Lead for Visa in India & South Asia. He began his career as a consultant with KPMG in London, spending a majority of his time helping the firm set up its global enterprise blockchain and crypto asset advisory practice. He moved back to India in 2018 and joined Koinex (then India’s largest cryptocurrency exchange) as Director of Business and Strategy, before assuming the same role at B2B-SaaS startup FloBiz. He is currently the co-founder of Tigerfeathers, a newsletter (and soon to be podcast) that features the coolest stories from the Indian tech ecosystem. He doesn’t know why he’s writing this in third person, but whatever.

![The Map of India, Arabia, the Horn of Africa the and Indian Ocean by Pedro and Jorge Reinel of the Miller Atlas, a Portuguese illustrated atlas dated from 1519. [3801 x 2661] : r/MapPorn The Map of India, Arabia, the Horn of Africa the and Indian Ocean by Pedro and Jorge Reinel of the Miller Atlas, a Portuguese illustrated atlas dated from 1519. [3801 x 2661] : r/MapPorn](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa2adb7a3-f742-4bab-b2bb-6b34aafd86ba_3801x2661.jpeg)

Nicely written - Rahul. I love the conversational style and the 'lucidly flowy' language weaving in some metaphors. Your research is comprehensive... Keep it up!!! This will now be one of my weekly long reads fix.

Hi Rahul, I just started reading this and being in Last Mile domain, I totally understand the significance of Geospatial data. Saying that, could you kindly elaborate more on this or point me to a source: "Last mile delivery costs are 3x more in India than they are in the US". I would love to understand this better.