Hey folks👋

Welcome to the 132 new Tigerfeathers subscribers who’ve joined since our last piece.

In April 1973, the Government of India launched Project Tiger to promote the conservation and protection of tigers on the subcontinent. From 2010 to 2022, the number of tigers in India more than doubled as a result of these efforts, crossing 3000 big cats as per (purr?) the results of a 2022 census report.

We launched this newsletter in mid-2020. Now, we’re not saying there’s a correlation between the growth of Tigerfeathers and the population of tigers in India, but just to be safe you can click here to do your part👇

Where were we?

In Part 1 of this series on mapping and geospatial technology:

- we talked about how the ‘smartphone age’ should really be called the ‘digital mapping age’

- we covered the history of mapping in India

- we learned how geospatial (location-based) data is the invisible lubricant to much of the digital economy

- we learned how India’s concerns over national security meant that mapping was historically considered the domain of the Central Government, largely cordoned off from private sector participation

- and finally, we talked about the landmark series of policy changes that were introduced in 2021, and how they embolden our geospatial sector to become an engine of economic progress in India

If you made it all the way to the end of Part 1, I’ve left you a piece of my heart in my will. Just kidding (sorry), but if you did make it to the end, you know that we promised to bring this topic to life via the case study of a startup that’s been on the mapping train since long before it was cool.

That startup is NextBillion.ai.

Nice, what do they do?

NextBillion is tackling a problem faced by almost every organisation in the digital age - the need for contextual maps and location intelligence. Simply put, they help companies build their own custom digital maps (I promise I’ll explain what that means and why that’s a big deal).

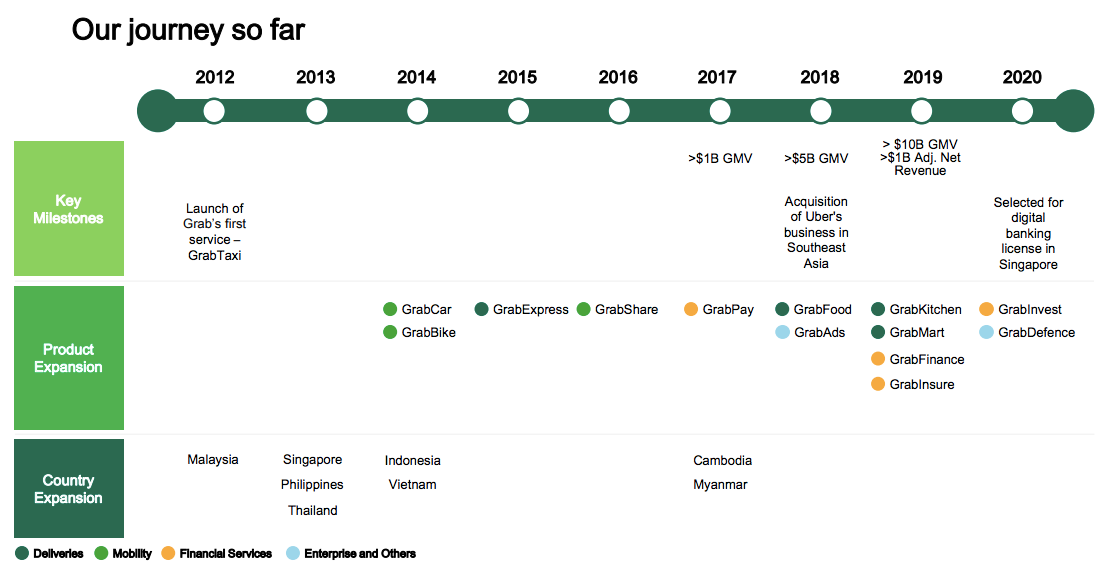

It is the brainchild of Ajay Bulusu, Gaurav Bubna, and Shaolin Zheng, who set up shop in early 2020. The trio were founding pillars in the mapping team at Grab, where they learnt firsthand how crucial mapping was to the unit economics and consumer experience of modern digital products.

The founding team at NextBillion envisions their software humming in the background of hyperlocal startups, e-commerce companies, ride-hailing and delivery apps, logistics and emergency services, smart cities, drones, and everything in between.

Their goal is to become the ‘AWS for mapping technology’. It is a lofty aim, validated by a $21 million Series B funding round led by Mirae Asset Capital in mid-2022 (with participation from existing investors like Lightspeed Venture Partners, Microsoft's Venture Fund, M12, and Alpha Wave Global).

With offices in Bangalore, Hyderabad, San Francisco, and Beijing, they are building for a global market. They believe their solutions can help any company anywhere in the world that relies on geospatial data to better serve its customers, improve its operations, and unearth opportunities it didn’t know even existed.

NextBillion is what happens when you task smart people with solving interesting problems and then get out of their way. I don’t know if it’s the highest ratio of I-didn’t-know-that(s) per minute I’ve experienced when learning about a new company, but it’s probably in the top five. There’s almost no chance you come away from this piece without a new insight into the underlying magic that powers our digital economy.

So today’s piece features:

- an introduction to spatial analysis and location intelligence

- an exposition of the ‘mapping problem’ faced by organisations in the digital age

- an overview of enterprise mapping

- a deep dive on NextBillion

Cool, do I still need to read Part 1 to understand this piece?

If you haven’t read Part 1, you should still be good to go. But for more context (and great memes) on mapping and geospatial tech, I’d recommend starting there.

Anyway, let’s get moving.

First up, to keep things consistent, we begin with a little detour through London.

Again???

Yeah.

In 1854, 188 years after England had shaken off the scourge of bubonic plague, the city of London found itself battling its third major outbreak of cholera. The disease had ravaged Britain through much of the 19th century. It was considered the ‘fear of the unknown’ because doctors had yet to identify its cause or treatment. All they had was a hunch that it had originated from Asia and most likely spread through particles in the air. At the time there was a little understanding of the nature of germs and how they transmitted diseases. The prescribed treatment for cholera ranged from improving the ventilation in your surroundings, to asking forgiveness from God.

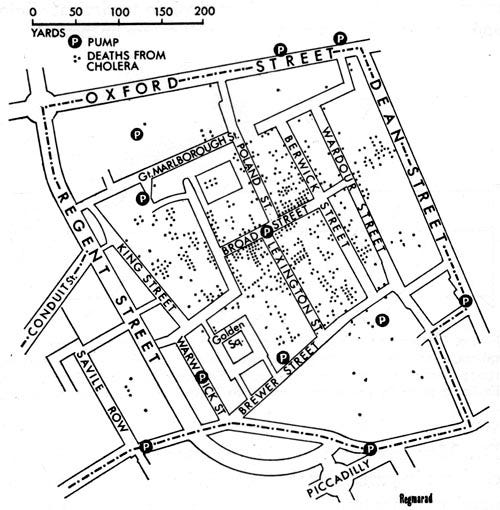

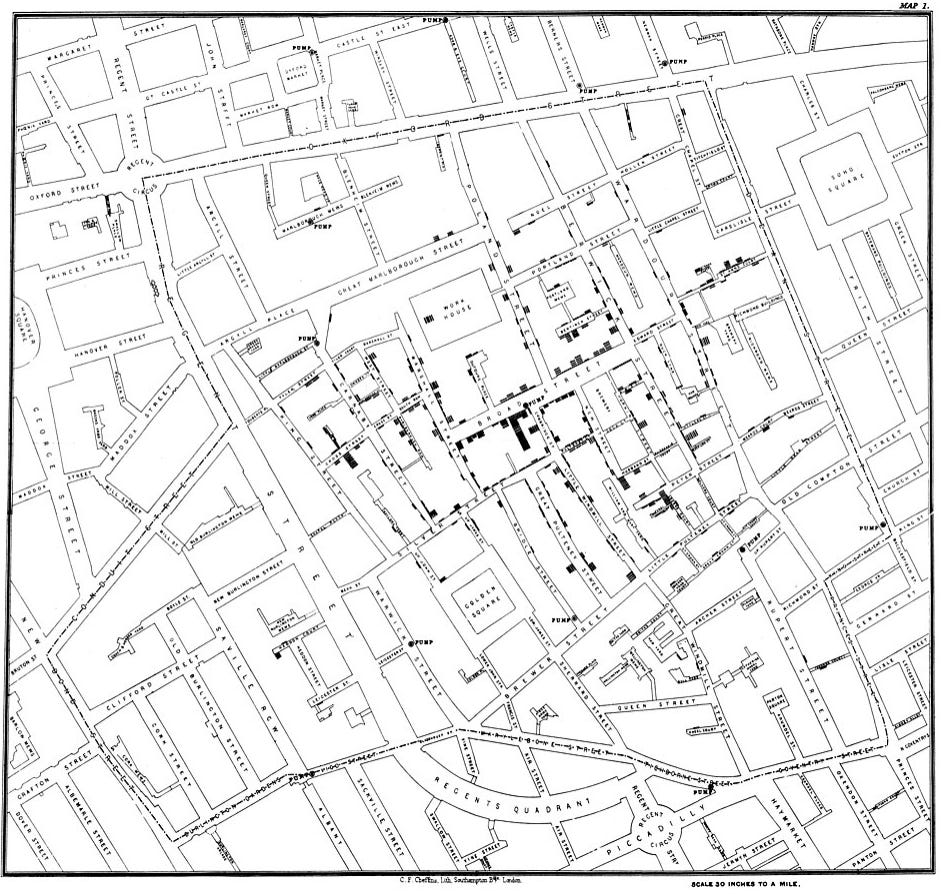

A British physician, John Snow, decided to investigate the cause of the outbreak. In the early years of his medical career he had studied previous instances of cholera in London. He had a suspicion that the prevailing wisdom around its contagion was incorrect. His methodology (innovative in Britain at the time) was in gathering information about the cases of deaths in households over a particular area, and plotting them onto a map of the locality.

Astonishingly, he found that the majority of the deaths were clustered around a single street (Broad Street in the map below). And specifically, he realised that the houses on this street were being supplied with water from the same pump - a pump, it turns out, that had been contaminated by sewage from the nearby River Thames.

John Snow had validated his own hypothesis that cholera was really a water-borne disease and not one that spread through the air. He instructed the local council to disable the Broad Street pump, bringing a measure of respite to citizens of London. His findings were crucial to helping usher the end of the ‘third cholera pandemic’.

He was subsequently credited with making one of the biggest breakthroughs in the study of diseases (and is appropriately considered one of the ‘fathers of epidemiology’). His methodology was key to shepherding the development of pathology, sanitation, and public health in England in the years that followed.

Great story, why is that relevant here though?

Because John Snow didn’t just break new ground for the field of epidemiology. Yes, his use of data, charts, and statistics to track the contagion of cholera has now become standard practice in the way we predict and manage the spread of diseases. But more relevant to us is the fact that his experiment is considered one of the earliest examples of ‘spatial’ analysis.

By combining math and maps, by pairing technology and geography, he was able to glean new insights about the world around him. His ‘Cholera Map’ helped to bring a public health crisis to life, allowing citizens and officials to make better decisions about their safety and sanitation.

That type of analysis is now commonplace. Corporations and governments use spatial analysis and geospatial data and to solve all kinds of problems today. To recap from Part 1, ‘geospatial’ refers to information about objects and events on the surface of the Earth. It includes everything from crime statistics in an area, to travel times between two routes, to drone imagery of a plot of farmland, to recordings of sea level temperatures, to the migration of wildebeests across a savannah.

Spatial analysis based on this data helps to inform business decisions such as where to open a retail store to maximise foot traffic, or where to plant crops so they can be irrigated by nearby water tables. Governments may use these findings to plan responses to climate change or disaster relief, or even to decide how many health and law enforcement personnel are required within a particular neighbourhood. Organisations like the International Olympic Committee will incorporate a spatial analysis to assess whether a city has the right infrastructure to host an edition of the Games. And so on.

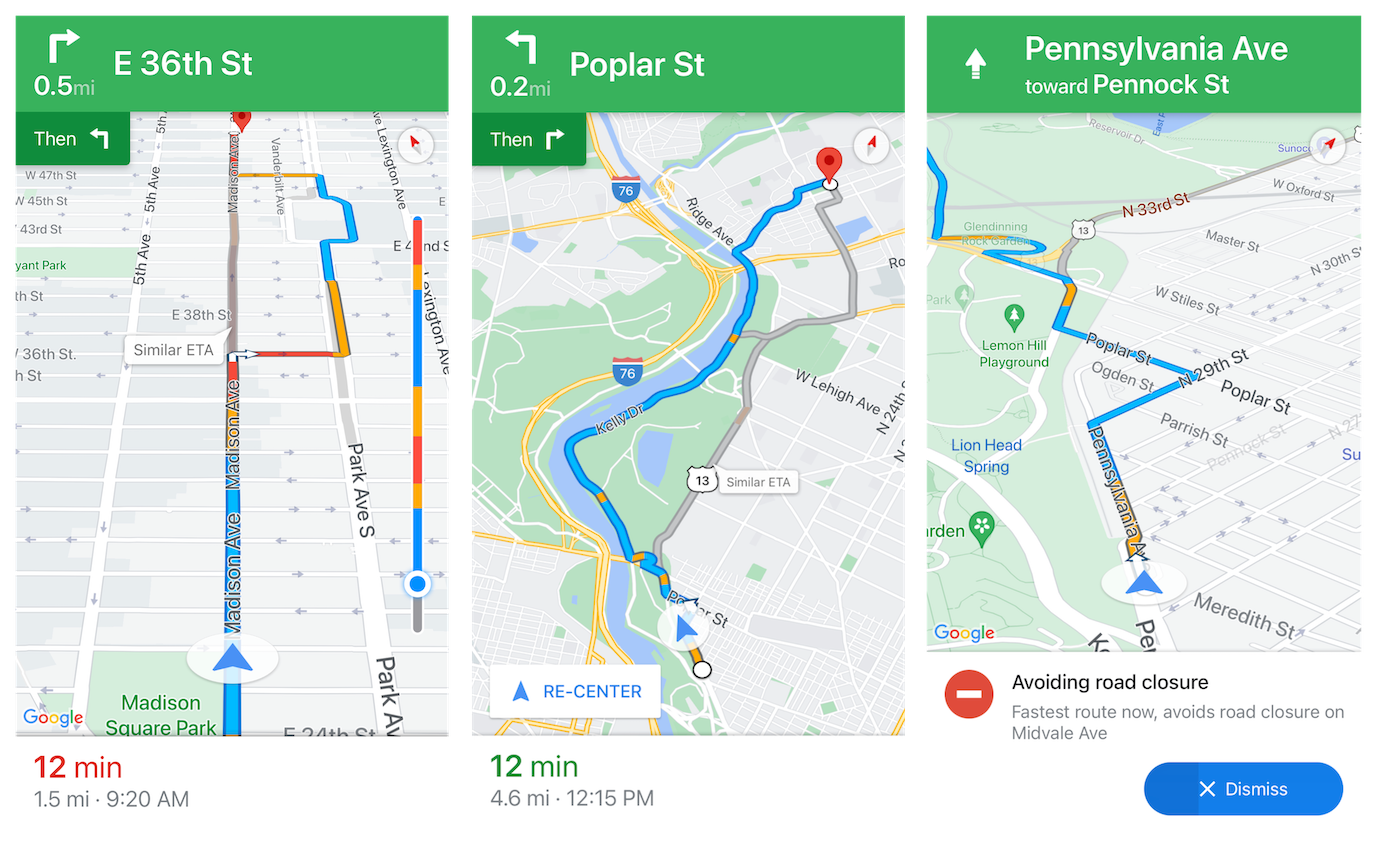

Unbeknownst to the average smartphone user, we benefit everyday from hyper-modern instantiations of John Snow’s rudimentary spatial analysis. Ever since Google and others made cartography a casual part of our routines, an entire generation of consumer tech apps have sprouted from the fertile grounds of the digital maps on our phones. For consumers, there are countless ways in which mapping has become indispensable in our lives.

For things like tracking the delivery of your packages.

Or to find out where your friends are.

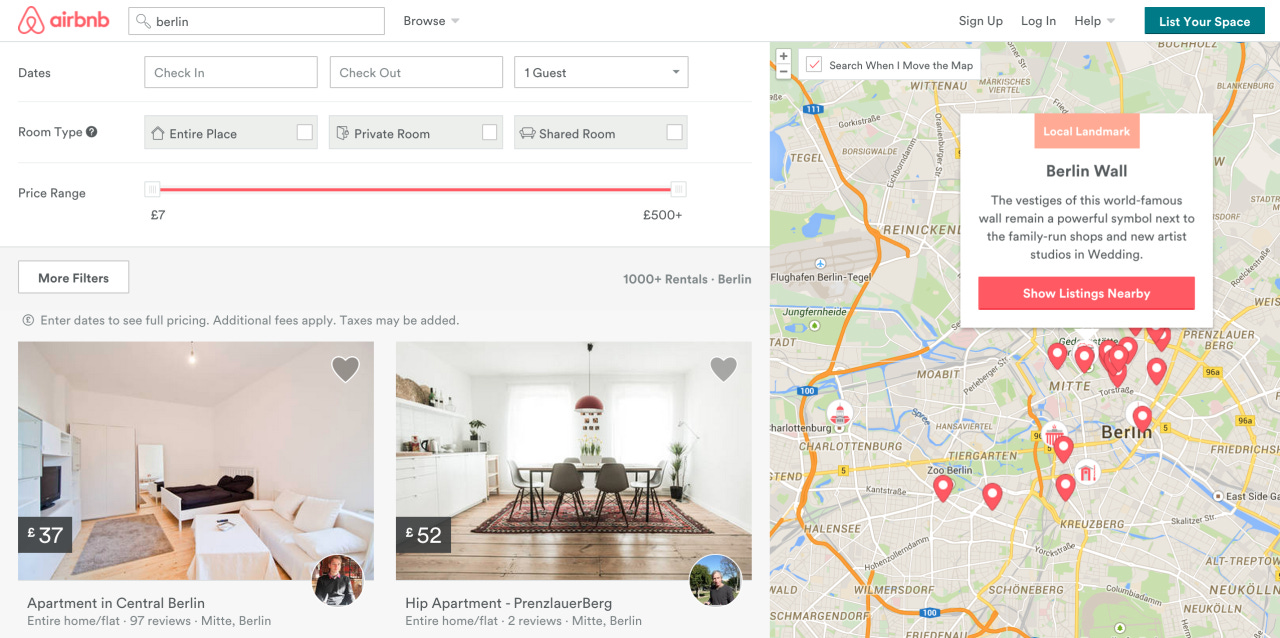

For helping you decide where to travel.

Or where to stay in a new country.

And how to eventually find your way home.

So you’re saying we’re all hopeless Mapaholics?

I’m going to ignore that.

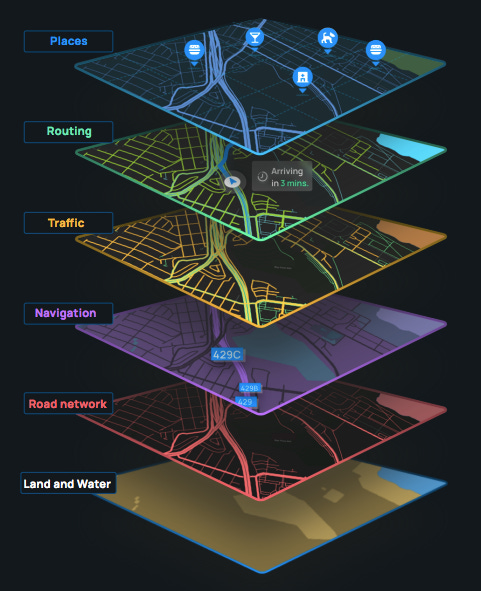

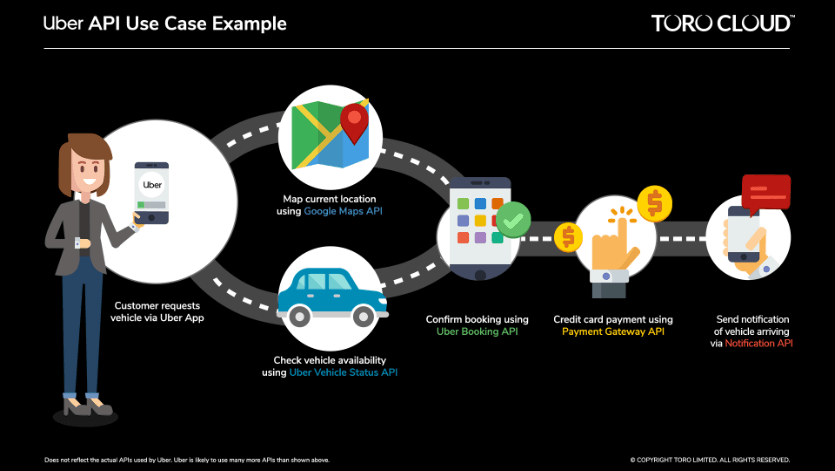

Anyway, I’d bet that you probably haven’t given much thought to what happens at the other end of your applications. Between you and your maps sits a service provider (and often multiple service providers) that operate a jumble of whirring machinery and slick APIs to make sure that the information on your screen is accurate. There is a cluster of moving parts that needs to be tamed so that the map you see is a true reflection of spatial reality.

This includes critical steps and components like:

- GPS receivers on your phone getting accurate time and location signals from satellites orbiting the Earth

- your telecom provider triangulating your phone’s location using signals from cell phone towers and wifi routers

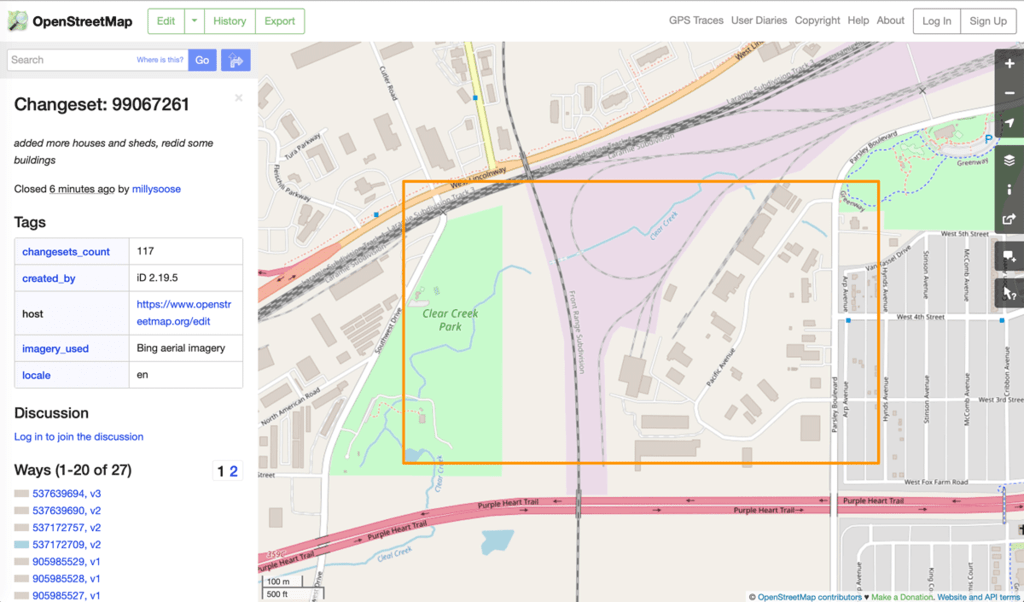

- smartphone applications communicating with mapping providers like Google Maps, OpenStreetMap, MapMyIndia, and others via APIs

- mapping providers assembling a puzzle of data from satellites, planes, street cameras, open source databases, social media, public transport schedules etc to construct their digital representations of the world

- developers whipping up their own proprietary models and algorithms to mould a map to suit their purpose

The stakes are high. For consumers, a bad map could lead you to taking a dangerous route in a foreign country, paying extra for your Uber ride, or worse, giving your girlfriend the wrong ETA when you’re already late for dinner.

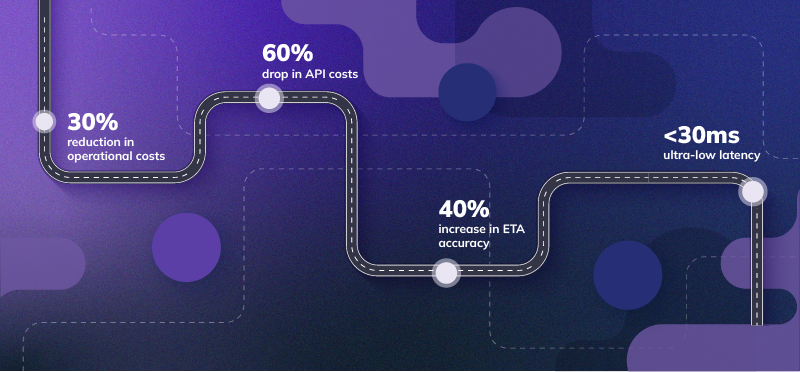

For enterprises, mapping can be a matter of commercial life and death. This is especially true in this cut-throat era of consumer technology where competing products veer suspiciously close to commoditisation. In this arena, shorter ETAs could be the difference between you choosing Google Maps or Apple Maps. Lower fares (from route optimisation) could be the reason you typically flick open Uber instead of Ola. A better tracking system might endear you to Flipkart instead of Amazon. Smarter fleet management could mean that Dunzo has more delivery agents to serve your neighbourhood than Zepto.

For these businesses, better mapping can yield cost savings and improvements in ETAs (Estimated Time of Arrival) - small efficiencies that add up quickly when you’re dealing with millions and billions of transactions. If the long-term success of these companies rests on their ability to extract economies from scale while keeping their customers happy, they cannot afford to treat mapping as an afterthought.

Given the importance of wrangling geospatial data to harvest the bounty of the digital economy, mapping can no longer be seen as just an ornamental addition to an application or website. Instead, as it was in the time of kings and conquerers and colonisers, mapping is another front to be conquered in the theatre of commercial warfare. It must be as present in the CEO’s office as it is on the product roadmap.

That’s the future that NextBillion.ai envisions.

In a nutshell, they help companies use AI to solve highly complex location problems. They foresee a world of a ‘billion different maps for millions of enterprises’, where every company manages its own bespoke spatial playground to address their unique location-related challenges.

“The core part of why we exist and what we are building is the fundamental belief that in the next ten years, location technology will play a huge role in many ways for both consumers as well as businesses. Over the next five years, the opportunity is massive.”

- Gaurav Bubna (CBO - NextBillion.ai)

But how did they even know the opportunity existed?

To answer that question, we have to rewind back a little bit to 2017 - back to the offices of Singapore-based mobility startup Grab.

NextBillion’s three co-founders had forged their own individual paths to Grab. They had each begun sketching out the contours of a successful career that already featured a number of colourful pitstops.

Ajay Bulusu had grown up in Hyderabad and studied in the UK at Warwick Business School. He returned to India post graduating in 2009 after being confronted with an unfriendly European job market that was still licking its wounds from the financial crisis. He would spend the next seven years cutting his teeth in various roles and regions across the corporate landscape. This included stints at blue-chip companies like Google, Indeed.com and American Express, that allowed him to sample the bustle of New York, Tokyo and San Francisco.

Gaurav Bubna was born and raised in Mumbai, and graduated from IIT Mumbai in 2009 with a degree in computer engineering. Passionate about all things “math and deep tech” he moved from an analyst position on Wall Street to being the founding member of recruitment startup Zlemma. He then honed his Product chops at Ola before finding his way to Singapore at Grab.

The final third of the triumvirate is Shaolin Zheng, who grew up in China and majored in computer science at the Beijing University of Technology. His experience consisted of a number of senior engineering roles, including as the co-founder and CTO of Youche, a former ride hailing platform based in Beijing. Fun fact - Shaolin is the only one out of the three who has an official designation at NextBillion (as Chief Technology Officer). Ajay and Gaurav are title-less ‘co-founders’ flitting across different Product, Business, and Operational verticals at the company.

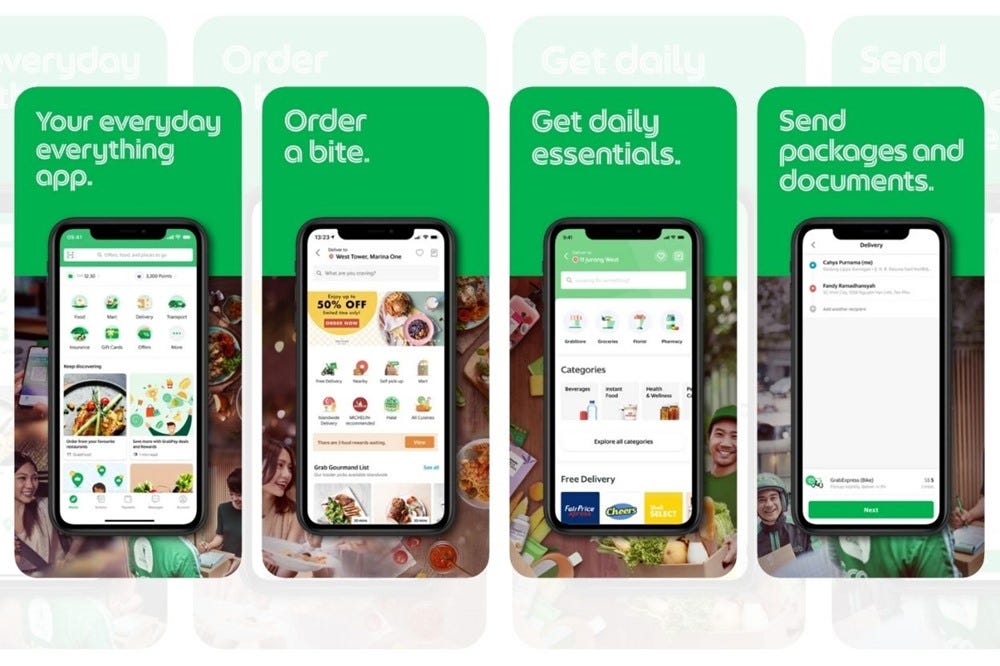

Each of their winding paths led them to Grab in 2017. With the gig economy in full swing, 5-year old Grab was in rocket-ship mode. It had recently crossed an impressive milestone of one billion rides, at one point boasting 66 concurrent rides in one second across all seven of its markets in Southeast Asia.

Sounds like a well oiled machine?

Not precisely. Ride hailing was still a relatively new phenomenon in the Eastern hemisphere. This part of the world had its own infrastructural deficits and behavioural challenges. For all its impressive numbers Grab was still swimming in a shark tank of seasoned competitors (like Uber and Gojek) and needed to exploit every operational edge it could find.

In late 2017, Gaurav, Shaolin and Ajay were entrusted with laying the foundational stone of the newly created Mapping and Geo Data team at Grab. Gaurav recalled that:

“Grab was going head to head with Uber at the time. The leadership at Grab had discovered that every time we examined customer issues and complaints, the trail seemed to lead back some issue around mapping. We were using Google Maps at the time but it evidently wasn’t working as well as we hoped. It was the same product that Google provided to Uber, but for some reason it worked well for them and not for us. So our team was given a problem statement, which was to figure out why this was happening, what we were doing wrong, and how we could improve the mapping experience at Grab.

We did some further digging and realised that at Grab we had just half an engineer working on anything maps related (whose main role was just to handle the integration with Google Maps). Uber, on the other hand, had a 300-member maps team. China-based Didi also had around a 300-member maps team. We just couldn’t figure out why you needed so many people to manage a Google Maps integration”.

They went down a mapping rabbit hole - reading whatever they could, attending mapping talks and conferences, combing through their data, and speaking to people who had already found an answer to their conundrum.

“Our quest led us to realising that the majority of issues that customers report are, in one form or another, mapping or geospatial related. This was validated by a report from Accenture at the time that suggested that as many as 55-60% of customer complaints in mobility services can be attributed to the same cause.

For instance, the most common complaint was around the variability of fares paid by customers. Fares have a strong mapping component because they are determined by how long the trip takes. If your map is unreliable and the driver can’t find you, or he drops you off at the wrong place, that would lead to increased fares and unhappy users. Similarly, we found that out of the top 10 issues faced by users, seven of them were related, in one form or another, to improper mapping”.

Grab began to invest more into its geospatial data practice. The Mapping team grew from five people initially, to 50 people, then to 100 people, and finally to 250+ people in the next three and a half years. The company made strategic acquisitions to hone its location intelligence capabilities. It adopted a more pragmatic approach to mapping that optimised for the needs of its drivers and riders. It developed algorithms that governed the movement of pieces on Grab’s geospatial chessboard.

Eventually, their role changed from problem seekers to problem solvers. When they attended conferences now people came up to them asking about their approach to mapping. They frequently heard anecdotes about the superiority of Grab’s services. People shared stories about how they were “at this hotel or airport trying to hail a cab, and Uber and Gojek didn’t work, but the Grab driver somehow managed to come to my exact location.”

Gaurav recounted how:

“We had this one funny meeting with representatives from a major mapping company at the time. They didn’t know that we were building this internal mapping capability at Grab. One of their executives was opening the Grab app and commenting on how the ETAs we displayed were always on point, not realising that it was a result of our efforts and not because of their service! They wanted to learn from us because their maps seemed to work better on Grab than it did for other ride hailing companies”.

They were seeing tangible and quantifiable results from their tinkering. The ‘Geo’ team began to drive significant cost savings and margin improvements at Grab. Organically, they began fielding requests from other tech companies asking if the Grab team could help solve their own mapping challenges. The location opportunity began to reveal itself, and the seeds of NextBillion were planted.

By the end of 2019, they realised they were on to something.

Wait a minute. It sounds like a lot of ‘enterprise mapping’ was just making improvements on the same Maps product that everyone used. Couldn’t Google have solved a lot of these problems? How do they fit in to all of this?

Google was the elephant in the room. The company has shape-shifted from partner to antagonist to competitor at various points in the NextBillion journey. In the 2010s the spectre of Google loomed large over almost every single major consumer tech company that was conceived in this era.

It makes it easy to forget that Google Maps was initially conceived as a consumer product. It was launched as a web app in 2005, seen as the next frontier for Search and Ads. Google saw the ‘Map’ as an important platform that would serve as the future base for commerce.

Google’s Map was innovative in its architecture, allowing for greater interactiveness and functionality than any other digital mapping application that had ever existed (we probably still take for granted how much easier our lives are because of Google Maps). Google treated it as a dynamic platform instead of a static snapshot. Over the years the company invested heavily to improve the accuracy and usefulness of its product by integrating satellite and street view imagery, updates from public transport portals, better navigation services, business listings etc.

While it was always considered a groundbreaking invention, it really bloomed in cultural relevance once Google planted a digital map into the soil of our smartphones in 2008. Google Maps became a membrane that connected consumers and enterprises in the digital economy. At Grab, they even had an internal saying poking fun at their own dependence on maps - “No map, no app.”

Gaurav recalled how:

“Strategic dynamics had started to emerge in the market by the late 2010s. Google wanted to get in on the action in the gig economy. They had realised that Google Maps was a critical enabler to all of these digital products, and it shouldn’t be hard for them to implement steps to drive these use cases from inside their own application. For example, they felt like ride hailing could happen from within the Google Maps app itself and not only on Uber or Grab. They began testing out features to enable things like this. Most of these initiatives were backtracked eventually, but it posed a conundrum for us at the time. Like what if they launched self-driving cars for their ride-hailing business in the future? What if they ramped up the price of using Maps?”

Those concerns would prove prescient. Google’s coup de grâce came in July 2018 when they changed the pricing structure for using the Google Maps API. It was an atom bomb on the digital economy. Overnight, a utility that had been practically free to use was now prohibitively expensive for companies with high traffic.

“Mapping costs increased 14x for smaller startups and 2-5x for bigger companies like Grab. These consumer tech companies tend to be low margin and high volume businesses, so mapping costs are a material component of their unit economics. Google made it unsustainable for these companies to continue using Google Maps. They justified it saying that Google Maps was a premium product. We also heard from some corners that some Google executives believed they were still underpricing their APIs given the importance of their services. We think it’s safe to assume that their prices will continue going up in the years to come.

From their perspective, maps had traditionally been a cost centre for Google. They had invested heavily in mapping over the years, subsiding that cost with revenue from Search and Ads. They thought it was time to start reaping the fruits of their labour”.

How did that affect our heroes at Grab?

For one, it scattered any lingering mist that was preventing them from clearly seeing the enterprise mapping opportunity in front of them. And two, it validated their thesis that although Google was the undisputed king of consumer maps, it wasn’t the answer to mapping questions faced by enterprises. While the price increase was a major catalyst to find a more sustainable way of doing mapping, the NextBillion team had already concluded that Google Maps couldn’t meet the technical requirements for new age consumer apps.

Gaurav revealed on a podcast in 2021 that:

“There were just things we needed to do which existing map providers could not do. A simple example of this is latency and scalability and throughput. If you’re doing a whole bunch of orders or rides or logistics planning or delivery planning, you need to be able to call these APIs at very very large volumes. I believe in my previous job [at Grab] we were doing 5 billion API calls a day. Now at that kind of scale, firstly it’s extremely expensive. But more importantly if I wanted to use Google, you can’t use it, because if you’re trying to make, say, 100k API calls per second, Google caps out at 1000, as an example.

It’s a technology thing - because anything hosted across the network which is not inside your cloud environment, it just cannot support that kind of scale. Anecdotally, we’ve heard from Uber that their internal mapping service caps out (the maximum load it supports) is up to 1 million API calls per second. That’s like 1000x of what Google claims it provides as a maximum limit to its customers. So scalability is another issue.

Perhaps most importantly, they had stumbled upon a kernel of truth - the kind of discovery from which an entire company can be excavated.

“In our business we’ve discovered that ‘one map doesn’t fit all’. Which is to say, however great Google or MapBox or any of these other companies like Here or TomTom might be, the reality is that they have one view of the world”.

For consumers, it doesn’t make a difference that everyone has access to the same map. You and I don’t need custom versions of Google Maps. For companies, this isn’t true.

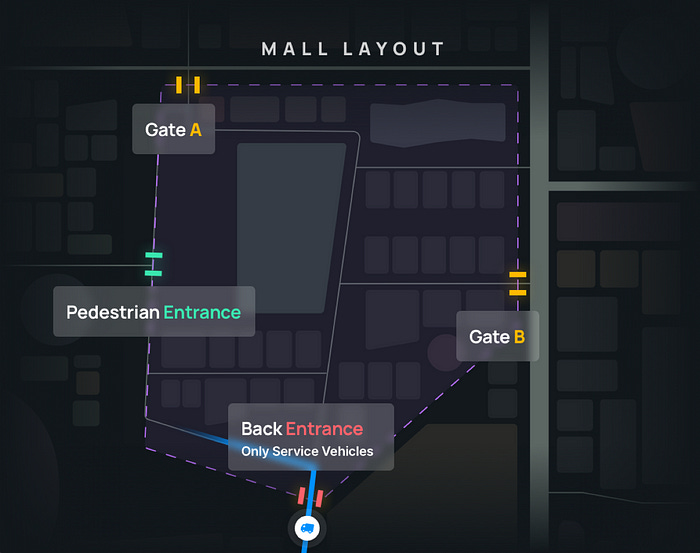

For instance, if you wanted to reach a major department store in your city, you would look at Google Maps and it would guide you to the main entrance of that store. But your Uber driver would want to know which entrance you were exiting from, or which side of the street you were standing on, in order to come directly to you. Amazon would need to know which is the main loading/unloading dock to deliver its shipments efficiently. A Swiggy agent would need to find the staff entrance to deliver lunch to employees working at that store. That’s four different mapping requirements for the same location based on four different contexts.

The problem wasn’t that Google wasn’t good enough or that there weren’t other competing mapping providers. The issue was that all of these companies took the same approach of building a homogenous mapping application that enterprises could use ‘off the shelf’, but couldn’t tailor to suit their specific purposes.

Take another example, if you were trying to plan a drive from Mumbai to Jaipur, Google might tell you it would take 18 hours. But if you were operating a fleet of trucks, your drivers might typically stop to rest or grab some refreshments. They might have to wait at toll booths on the way. They might be prevented from travelling through certain urban areas after 6 pm. You might even be aware of certain roads that are troublesome on Saturdays because neighbourhood kids like to play cricket on the street. The actual journey time could be closer to 45 hours. So you wouldn’t be able to plan your logistics business using the information you got from Google.

Here, you’d want a platform that allowed you to plug in your own data and specifications, one that guided you on how to optimise your service delivery - almost like having your own personal spatial sandbox. You’d want to be able to enrich this platform with your own targets, your own insights, and your unique vantage point on the commercial (and physical) landscape you inhabit.

In February 2020, Ajay, Gaurav and Shaolin decided to build that platform themselves. They left their roles at Grab to launch their own startup - NextBillion.ai.

February 2020? Not ideal timing, no?

Depends on how you look at it. Sure, on one hand, they were starting up just as the world was reckoning with the onset of a global pandemic. But from a personal standpoint, it was as good a time as any. Ajay mused that:

“When you’re starting up, the two toughest things to do are finding a team and finding a problem. We had both. The three of us were each in our 30s. We had considerable experience, complimentary skills, and we trusted each other. We thought we had gone as far as we could with Grab. Sure, we could easily have spent another few years planning and waiting for the perfect moment. Or we could just go for it.

We weren’t distracted by the idea of building a billion dollar company or a ten billion dollar company. Our goal was to have fun, and to take on a professional role with more responsibility. We didn’t know if there was a company worth building but we knew that it was a problem worth solving. We said we would give it a year and see how things went”.

On the commercial side, the pandemic (and ensuing lockdowns) presented both opportunities and challenges. Gaurav admitted that:

“It definitely made life a little harder. For one, we thought enterprise mapping was the biggest opportunity, but enterprise sales was very difficult to do as a new company without face-to-face meetings. None of the large enterprise clients would sign a $0.5 million contract without meeting in person. We had to pivot to a more bottoms-up approach that appealed to smaller start ups. We were also initially targeting 2-3 industries like ride-hailing, transport and deliveries. In early 2020, for example, ride-hailing went to zero, but deliveries went up. Our first client was actually a social media giant that wanted us to help them with Map Data Management. We had to keep adapting to what the market gave us”.

Fundamentally, though, the pandemic didn’t change their mission of ‘enabling movement’ anywhere in the world. Ajay recalled in a interview last year that:

“…the pandemic taught us that if people don’t move, things move to people. In either case, a map is very important; without it, you can still move things, but it’ll be expensive or take longer, or you’re unable to track things. The efficiency you can gain with better maps is huge”.

They registered their new company in India’s startup capital (i.e. Singapore). Jokes aside, in recent years Singapore has emerged as popular jurisdiction for companies starting up in the region because of the relative ease-of-doing-business it provides. In the case of NextBillion, it was where the three co-founders had spent the previous few years working at Grab. But also, as Gaurav tells me:

“Setting up in Singapore signals context that your business intends to have global ambitions from Day 1. Companies based in Singapore typically have offices in different parts of the world. They tend to have business interests in places like Hong Kong, Taiwan, Australia etc. The tech ecosystem might be more mature in India, but there was a ready client base for us in Singapore. A bunch of our initial customers were companies from the region that we had already had a relationship with and who were familiar with our mapping work at Grab - like Gojek, for example. We decided that India and Southeast India would be our target market. If we were successful in building for emerging markets, our hypothesis was that we could then look to the US and Europe”.

Their vision, experience, and early traction helped them raise a $7 million seed round from Lightspeed Venture Partners and Alpha Wave Global in June 2020. The team had all the ingredients they needed to push on.

Hold up, you still haven’t said what NextBillion actually does?! What are they even building? Another mapping company like Google?

NextBillion is not building a mapping company. They are building a platform for spatial data management. As we learnt earlier from John Snow’s cholera study, a map just happens to be the best way of expressing spatial data to derive location intelligence that aids better decision making.

They are less of a mapping company and more of a location-tech company that uses ‘mapping’ as one of their inputs. Contrary to other consumer tech giants like Google and Apple that have constructed proprietary digital maps of the world, NextBillion hasn’t actually built its own map. Rather, they’ve built an engine that can ingest all kinds of spatial data - including maps from third parties - in order to solve various location-related challenges. They are ‘problem-first’ as opposed to ‘map-first’.

Ajay illustrated this point, saying that:

There are more than 500 routing companies in the world. We are not the first or last. However, all the other companies are built on existing maps and map platforms. These maps were designed for consumers in mind. They weren’t built to focus on specific solutions or business challenges. So companies that claim to provide routing solutions using these maps all face the same constraints because they are reading from the same script. They are unable to make changes to the underlying map data to suit their purpose.

If you’re an iOS app that’s using Apple Maps, you can’t add your own road closures, you can’t draw new points of interest, you can’t draw your own geofences. On the other hand, for example, we provide tools that let companies tailor unique maps for different vehicles in their fleets. They can prescribe specific business logic while designing delivery routes for bicycles, trucks, scooters etc. You can have one map where you can say that certain roads are closed to trucks because there’s a Formula 1 race happening. You can have a different route for a delivery agent using a bicycle. You can even have a map that takes into account the behaviour and preferences of an individual truck driver in your fleet who likes to stop for bathroom and chai breaks.

You can do all of this using the tools we provide. We can help you dispatch, schedule or allocate anything that moves. We are optimising resources, not routes. Our edge lies in our understanding of the business layer on top of maps. Our North Star is to improve the operational efficiency and bottom line of our clients.”

Gaurav added that:

“What we’ve done in the last two and a half years is built an agnostic location intelligence platform that can solve for different use cases. The difference between us and other mapping companies is that other companies offer solutions based on the standardised maps offered by Google, HERE etc. We do the reverse. We didn’t start with a map. We decided to build a horizontal platform where any spatial data could serve as an input (3D images, open source maps, traffic data, historical trends etc). We can now us this nimble platform to tailor solutions for different verticals.

We are a great fit whether you are delivering a person, package or pizza.”

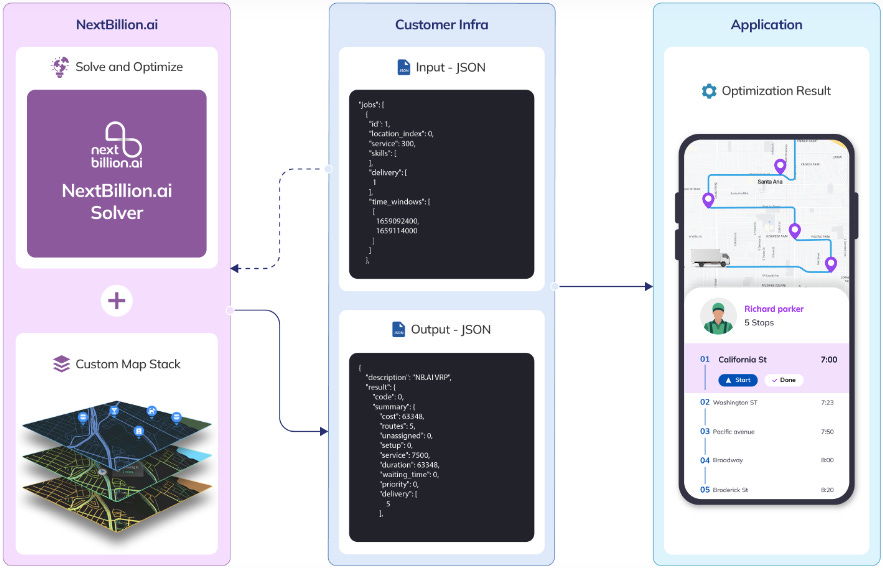

NextBillion currently focuses on two main solution categories:

1. Spatial Data Management - where they help enterprises build custom layers onto their existing maps (using proprietary data, third party data, open source data etc). Eg: they could work with a ride hailing company to create a custom map that depicts the best pick-up points outside all the train stations within a city based on historical data. It’s used by companies like Gojek and Coca-Cola to better manage their vehicle fleets.

2. Business Solutions - where they offer a number of APIs and SDKs for different use cases (route optimisation, fleet management, distance calculation, asset tracking, map visualisation etc). These solutions incorporate AI/ML models that the team has been tweaking and perfecting since their time at Grab. They are optimised to yield real business impact for ‘marketplace fulfilment problems’ like ride hailing, food delivery, hyperlocal commerce, logistics etc and can drive civic use cases like emergency response programmes, disaster response systems, smart cities etc.

This API-first approach is geared towards quick and painless solution implementation. It means they can use the same APIs for different sectors and use cases by making tweaks in the business parameters. It requires ‘zero code or additional development effort’. Ajay remarked that:

“Our API-native approach is what separates us from a lot of the legacy mapping service providers in the market. Most of these guys were ‘solution-first’ meaning they have to process your existing data and integrate with your ERP systems before starting. This can take upto nine months to close. It means they mainly target the most traditional enterprises and automotive players, not the MSMEs and modern age companies. We can serve everyone. A company with a fleet of nine vehicles and one with 10000 vehicles can both use the same set of tools”.

It’s a similar playbook to how you would integrate APIs from companies like Stripe or Twilio to enable sophisticated functionalities like ‘payments’ or ‘messaging’ for your products. NextBillion’s APIs allow enterprises to replicate the work done by an entire external mapping team in-house. They essentially “deconstruct what companies like Google do internally, and provide those same tools and components to clients in an easy-to-use manner.” It’s like having your own personal Google Maps team working on your specific use case and business requirement. For instance, as a logistics company, you don’t need to wait a month for Google or HERE to update their map with news of a recent road closure. You can make the edit yourself in your personal NextBillion-supported custom map, and see the impact of the change reflected instantly in the form of alternate routes for your drivers.

Right, so what’s their vision for the future of mapping? How do they fit into it?

Gaurav told me that:

“When people look at location tech from the outside they tend to think of it as a background thing - a frill that is ‘nice to have’. What’s not appreciated is the quantifiable amount of business value it can unlock. At Grab we drove triple digit millions in savings via operational improvements. A more sophisticated approach to geospatial data management resulted in a significant impact on our margins and bottom line.

We see the same thing with many of our big clients [at NextBillion] today. Engineers and Product Managers realise that location is important now. Three years ago that wasn’t the case. Back then location just meant integrating Google Maps. Now everyone in Product understands the stakes. But CEOs aren’t thinking of ‘location’ as a strategic item yet. We think this will eventually graduate from a VP and CIO level to a critical lever at the CEO level. That’s our big bet.

When that time comes, NextBillion wants to be in position to be the first name that comes to mind when people think of spatial data management. He added that:

“A map is not just one line item in a company’s budget. It’s more like a section. Mapping typically constitutes multiple line items that includes different components and tools, often from a selection of different service providers. Large companies will usually spend money on at least ten different location tech vendors. These companies’ internal teams are tasked with making this mish-mash of pieces work together. That’s where the complexity and inefficiency comes from.

Right now, NextBillion doesn’t offer all those ten items. Right now we offer a set of APIs and SDKs - modular components that can be plug-and-played as part of the clients’ tech stack. We represent just one of those mapping line items. Our vision for the future is to be a full-stack location platform. Any customer should be able to come with us with any location issue. We might build these capabilities ourselves or offer it via partnerships. But in essence, similar to how you can get all your ‘cloud’ requirements serviced by AWS, we want to offer a ‘Location Cloud’ that caters to any enterprise location requirement”.

But perhaps their strongest conviction is the idea that the ‘the future of mapping is decentralised’ - i.e. when it comes to enterprise mapping, ‘one size doesn’t fit all’.

Ajay elaborated on this maxim, stating that:

“Ten years ago (or even five years ago), location data wasn’t as abundant as it is now. That’s why centralised mapping providers like Google, HERE, Apple etc had a dominant position in the market. They undertook massive investment and engineering to gather geospatial data and package it in the form of high quality consumer maps. That’s why people used to think problem-first instead of location-first - they were constrained by what they could do with the underlying map.

If you look at a Google or a Mapbox, they are essentially saying ‘I have the best data, I have the best APIs, you can go use my stuff’. What we are saying is no matter how good those companies are, they cannot handle all the local nuances and features that are unique to your business. We are providing companies with the tools to build their own maps. So it’s not like we are saying don’t use Google Maps and please use NextBillion maps instead. We are saying, don’t use either. Instead, take these tools to build your own Uber Maps or Gojek Maps or whatever. You know your business and your situation better than us, so here are the tools you need to create a map to your own specifications and configurations. Anything you build is proprietary to you.

Mapping is no longer constrained by who owns the data. Because today data is everywhere. Consumer mapping hasn’t just been democratised, it’s been commoditised. There are now public and government sources of data, there is open source data from the likes of OpenStreetMap, and there is proprietary data generated by individuals and organisations. That’s why we get plenty of cross-pollination amongst the most popular public maps.

“The challenge now is how to combine all this data to make something useful. Every company is now asking what they can do with location data. In the world of advertising and marketing they understand this well. That industry has gotten good at parsing through data to understand their customers better - using it for things like footfall analysis, store location planning, targeted ads etc. We expect to see a similar phenomenon in the world of location and geospatial data for enterprises and governments who are sitting on proprietary data that no one else has.

For example, the Singapore government has its own authoritative national map called OneMap. It is basically a visual depository of the country. NextBillion is working with them to make it more navigable. For instance, including information about access points for senior citizens. They want to be able to do things like send a push notification to citizens to warn them when there’s roadwork happening in certain places. We are in the early innings of understanding the potential of location data”.

How does Open Source mapping fit into their story?

There were major instances of cartographic vandalism in the heyday of PokemonGo. Because PokemonGo relied on OSM maps for its augmented reality game, players realised that if they made certain edits on OSM, it would affect changes in the game. For instance, a common issue was people drawing fake lakes near their houses on OSM so they could artificially ‘spawn’ water-type Pokemon for them to catch. If she doesn’t understand 50% of the words in the previous sentence, she’s probably too young for you bro (Source: MDPI)

Still, the cost savings alone make it worth the effort to spruce up open source data (from OSM and others) and make it fit for enterprise use. That, incidentally, is what companies like NextBillion (and its competitors like MapBox) have gotten good at. NextBillion can take raw data from OSM, add their own AI/ML magic, equip it with modular tooling, and make it suitable for enterprise.

As Ashish Dave (CEO of Mirae Asset Venture Investments), who led NextBillion’s $21 million Series B funding round, said to me that:

“Enterprise mapping needs are only going to increase. What NextBillion has done is basically made an enterprise-grade version of OSM.”

How’s the journey been so far?

By Ajay’s count, NextBillion is on its third product iteration. The company cycled through different instantiations of its enterprise mapping mission before settling on the current modus operandi. The team admitted that early on they were almost innovating for the sake of innovating. Ajay said that:

“We’ve realised over time that it is easy to build technology but very hard to sell it. In hindsight it feels like for the first one and a half years we were building products that no one wanted. We had to change our approach from being ‘innovative’ to being commercially oriented. We now have a better understanding of our customers and of our own positioning. We focus on things that move the needle - like tweaking our ML models, improving our intelligence engine etc. We learnt that if you want to take on the big boys, you can’t do it in a year. These things take time. You have to make sure you’re built to last.”

From a performance perspective, they spent much of 2020 trying and testing their products with friendly clients who already had a prior working relationship with the team. They went from proof of concept to five customers across three continents by the end of the year. In 2021, they started to narrow down on the right product offering and the right market. They raised an additional $6.25 million as a part of an extended Series A funding round from Microsoft’s venture fund called M12.

In 2022, they found product-market fit. They grew their revenue by 3.5-4x, their customer base by 10x, and expanded their presence across 20 countries. They expanded their client base to include 100s of MSMEs in addition to larger enterprise customers. They entered strategic partnerships with geospatial tech companies to craft holistic solutions for their clients. They closed an aforementioned $21 million Series B round led by Mirae Asset Venture Investments - no easy feat amidst a difficult macro environment for growth stage capital.

Ajay says that:

“Right now we want to be the answer to the question ‘Google is too expensive, what should I do?’. Our dream is for anyone in the world - if they want to use location services - no matter how big or small, they should come to us. In the short term we are a good fit for businesses of some size (series A startups and bigger). We are not the right choice for hobby projects at the moment but hopefully will be in the future.

At the moment it’s a proper David vs Goliath battle going up against Google. It’s fun, but it’s also stressful. You don’t want to win on a price war as a startup because you can’t out-price Google in the long run. What keeps us up at night is wondering how to continue differentiating ourselves. We have to keep asking what makes us unique. How much better is our platform? Do enterprises love us for us or because we’re a poor substitute for Google? We don’t want to be seen as a budget option, we want to be seen as a better option that is also superior on cost”.

From a competitive standpoint, they are going up against a number of legacy players that have been around the mapping and location tech industry for several years like HERE, Google Maps and ESRI. These companies are involved in various activities across the geospatial value chain from map making to location analytics. As Ajay alluded to above, NextBillion wants to eventually compete on quality, utility and price. They still believe that their unique approach to the problem is what separates them from the pack.

“Right now there are several options if you’re just looking at a mapping provider or a navigation tech provider. Like HERE, for example. But these companies are decades old. They were built on the same thesis as Google - i.e. gather huge amounts of data, weave that into a map, and stick an application on top.

NextBillion is the opposite. We don’t want any data. We will take a mix of open data, closed data, or proprietary data and built software on top. The way we think about the problem is very different from how legacy players think about the problem”.

Perhaps their closest analogue is an American company called MapBox that also specialises in taking open source map data and packaging it for enterprises. It is a well-respected name in the enterprise mapping world, having raised $334.2M over seven rounds of funding with an employee base of more than 650 people. NextBillion is confident it can compete tenaciously, assured in the belief that its products and solutions are superior to MapBox’s on the count of customisability, scalability, performance, and flexibility of deployment modes offered.

Gaurav clarified that:

“While we see Google and MapBox as our main competitors, long term we see ourselves as a hybrid of Google and ESRI. Other well-reputed mapping companies - like MapMyIndia and TomTom - we see as natural partners rather than competitors. In any case, the big picture opportunity is not about any one company dominating mapping. It’s about growing the pie for everyone.

There was an inflection point for location in the 2010s when GPS became available on smartphones. It triggered the first set of applications like Uber. Our hypothesis is that in the next 15 years we will see an explosion of innovation in the location intelligence space. We will get the Uber experience in other areas - like with ambulances, or inside a mine, on a ship, or even in the Metaverse. The market will explode with new use cases as people become aware of the potential of AI and location data”.

That’s the future NextBillion is building for, where location data dictates more than just the time of arrival of your lunch order. As geospatial data becomes richer and more abundant, and as the current wave of AI innovation consumes all the products in our lives, NextBillion is positioning themselves to be the infrastructure layer that powers an entire generation of location-first applications.

👏👏…what now?

Now we wrap this up (for real).

In Marc Levinson’s book - The Box - he paints a picture of how the humble shipping container was one of the most important inventions of the 1900s. The brainchild of an American trucking magnate named Malcolm McLean in 1956, it didn’t just revolutionise shipping. In fact, it provoked the physical alteration of ports, cities, ships, trucks, and nearly every kind of cargo handling equipment, all of which were remade to accommodate the new shape of global trade.

Logistics was an expensive, labour-intensive exercise in the years following World War 2. Before the container came into being, ocean freight costs accounted for 12% of the value of US exports and 10% of the value of US imports. McLean’s eureka moment was in realising that the key to transporting goods efficiently was to hoist the entire truck onto the ship, rather than expend time and energy unloading and re-loading the individual contents of a truck. Containerisation had a profound effect on global trade, lubricating the physical movement of goods from territories all over the world. It was the logistical incarnation of the handshake.

In many ways the shipping container is to the physical economy what the map is to the digital economy. It is a platform that allows people to congregate on the same plane. It orchestrates the predictable movement of people and things. It forms the core ingredient for innovations that are so magical they often disguise the unassumingness of their source material.

“Everything today revolves around location. Either you move or things move around you. And all of that requires a map. That’s the piece that people miss because it’s so far in the back end. When people think about mapping they think about Google Maps. Google made mapping a commoditised product. But mapping isn’t just Google. Google may have built the greatest consumer map of all time, but we will be the name people think of when they think of the enterprise version of that. If every individual solves their location problems using Google, every enterprise will solve their location problems using NextBillion”

- Ajay Bulusu (Co-founder, NextBillion.ai)

If you’ve stuck with me for both parts of this series, for 20000 words on mapping and geospatial tech, give yourself a pat on the back. We’ve come a long way, you and me.

As we’ve learned, the superhighways of the digital economy are greased with bits and pixels, not oil and wax. I hope you’ve learned as much from reading this series as I have from writing it. If I’ve made you think twice about the geospatial underbelly that fuels your applications, or pay more attention to the maps that allow you engage with the world around you, I’ll consider it job done.

For now, take a break. We’ll see you next time around.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A big thank you to Rahul Matthan (Trilegal), Bhavik Merchant (SWANSAT), Saahil Deo (Zepto), Dhruv Jhaveri (Freight Tiger), Ashish Dave (Mirae Asset VC), Ajay Bulusu and Gaurav Bubna (NextBillion.ai) for taking the time out to chat with me and share their insights. I would be remiss if I also didn’t mention Rakesh and Rashi Verma from MapMyIndia; and Lalitesh Katragadda and Sanjay Jain, who, along with other tireless iSpirt volunteers like Rahul Matthan, have spent decades trying to overturn India’s draconian mapping regulations. The Indian geospatial sector owes much to their persistence and foresight.

If you made it all the way here and you thought this was a good use of your time, it would mean a lot to us if you took a couple of seconds to share this post.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rahul Sanghi most recently served as Fintech Lead for Visa in India & South Asia. He began his career as a consultant with KPMG in London, spending a majority of his time helping the firm set up its global enterprise blockchain and crypto asset advisory practice. He moved back to India in 2018 and joined Koinex (then India’s largest cryptocurrency exchange) as Director of Business and Strategy, before assuming the same role at B2B-SaaS startup FloBiz. He is currently the co-founder of Tigerfeathers, a newsletter (and soon to be podcast) that features the coolest stories from the Indian tech ecosystem. He doesn’t know why he’s writing this in third person, but whatever.

Awesome story and great details on geo spatial. One naive query is how AI can solve physical challenges in identifying right issues that need solving. Eg the story of an artist who collected hundreds of phones on a trolley and rode it on an empty street which then google maps said congested and to be avoided.