For our subscribers:

Let me start off by saying Happy Diwali and happy new year to all of you! This has been a dark and stressful year for many people, but I get the sense that the pendulum is beginning to swing back towards the light. Having said that, I spent all of December 2019 saying ‘2020 is gonna be amazing, I can feel the vibes’ - so my read on the pendulum is shaky, to say the least.

This newsletter has definitely been one of the bright spots for me this year. I’ve thoroughly enjoyed the process of writing these articles, and in large part that has been due to your generosity, support, and encouragement. When Rahul and I started this project in August, we hoped to get 500 subscribers by February 2021. We crossed that mark three months ahead of schedule; we are really grateful to each one of you for helping us reach this milestone.

Coming to the content at hand, I’m writing this piece in order to organize my thoughts and canvas feedback on a startup idea. It is an idea I have grappled with for some time, and I suppose this is an attempt to lay my thoughts out for internal clarity as much as external feedback. Readers are encouraged to leave their comments, criticisms, and other remarks on this anonymous google form.

The README

It’s a common refrain in the startup world that founders should ‘build solutions to real problems’, ideally problems that they resonate with on a deep level. To take it a step further, these sorts of ‘missionary’ founders who pursue an idea out of some personal or philosophical imperative are sometimes compared favourably against ‘mercenary’ founders who launch a company due to purely economic considerations.

Whenever I’ve sat down to ideate on startup business models, I’ve found that most of the plausible ones I come up with tend to fall on the mercenary side. I haven’t been able to synthesize many of my own problems into startups ideas that hold enough personal significance or economic allure for me to seriously consider launching them.

But there is one particular idea which keeps returning to my mind when I hear the phrase ‘missionary founder’. It is an idea borne from a personal problem, and it is one that punched me right in the gut and refused to go away. In this post, I will consider arguments and counterarguments for this idea. But before I jump into describing the solution, let's take a look at the problem.

The Problem

It's story time now, so let's get in the mood. This event took place last year on a June night in Mumbai. If you know Mumbai you’d agree that nights in June can be oppressively hot and humid, especially in between the frequent rain showers.

On this particular night I was playing football on a rooftop in the Lower Parel area, and the combination of humidity and urban air pollutant particulate matter created a fittingly heavy and foreboding atmosphere.

In the football game, there were two teams of seven players, with one common substitute who would swap in and out every time one of the players revealed the limits of his stamina.

During one passage of play, I found myself on the corner of the pitch that was closest to the substitutes’ area. As I scanned the field, I noticed a movement from the corner of my eye. Turning to face the distraction, I saw the substitute laying on the ground with his legs in the air and his hands reaching up to grab his ankles.

Although his motion closely resembled a routine hamstring stretch, something about the situation set off my alarms bells. I promptly walked off the pitch towards him, calling out to ask if he was alright. My cries were met with silence. As I walked into close range I was horrified to see why.

The substitute’s eyes had rolled back in his head, and his limbs were convulsing as if he was being electrocuted. I screamed to alert the rest of the players to the emergency, and turned back to face the patient.

The man’s face was sweating and his veins were bulging. His mouth was clamped shut and his face was beginning to turn purple. I’m not a doctor by any means, but I had seen enough sports emergencies on TV to know that one of the first things medics do when attending to unconscious players is to pull the tongue out to clear the player’s airways. It was clear that this man was choking on his own tongue, so I instinctively tried to open his mouth to dislodge the offending organ.

No luck, the man was biting down with full force and I could hardly even pry my fingers between his teeth. By this point most of the other players had congregated around us, looking on worriedly. The mood was one of complete panic - we had this massive 6’4” man writhing and choking on the ground, and our brains were too full of sports-induced adrenalin to think clearly.

As the man’s convulsions intensified, I grew more desperate and somehow jammed my fingers into his mouth. The bite force from his teeth was intense, and for a moment I was pretty sure I was losing my fingers. Luckily, one of the quick thinking onlookers jammed his iPhone into the man’s mouth and we pried his teeth apart and grabbed his tongue.

At that point the man began to retch and vomit, his convulsions showing no signs of slowing down. While we were relieved to hear him cough and breathe, we were still extremely panicked and confused about what to do next.

Could he choke on his tongue once more? What if the vomit blocked his airways? What position should we place him in? Was his life in danger? Should we rush him to the hospital? How do you safely carry a 6’4” convulsing man down multiple flights of stairs? What was happening to him anyway?

While we nervously eyed the patient, a few people began making calls. I called my family doctor - no response. Somebody called the patient’s parents. Another player called the 108 government ambulance helpline, which astonishingly kept ringing with no answer. A third guy called one of the more famous South Mumbai hospitals, but the attendant on the phone took an age to inform us how long an ambulance would take (45 minutes), and despite our pleas offered no real advice or assistance over the phone.

While we frantically tried different phone numbers and google queries for terms like ‘emergency fainting’ and ‘stroke or seizure first aid’, the man continued to vomit and shake. Mercifully, my family doctor called me back after my flurry of messages insisting it was an emergency.

The advice he gave me was to google ‘epilepsy first aid’. The first page of Google search threw up several links which looked simultaneously helpful yet misleading. As I tried to open them to scan the content, the trackers and ads embedded in the webpages slowed my phone down to a crawl.

Between the 14 of us, we eventually found a few websites and arrived at a consensus on how to position the man’s body. At the same time, we still had no clue whether we should take him to the hospital or wait 40 minutes for an ambulance.

Thankfully, the man’s convulsions seemed to abate, and after an ordeal which lasted a total of 15-20 minutes, he finally stopped heaving and regained consciousness. For us bystanders, the feeling was one of pure relief. But also shock. And also trauma.

Later on at home, I kept replaying the incident in my mind. Standing in the shower, I could see the image of the patient’s face seared into the back of my mind. The burst blood vessels underneath the skin of my fingers also provided a tangible memento from the incident.

Suddenly, it hit me. The urgent need for a solution to this very real and widespread problem. There are millions of emergencies each year in India, but there are few effective solutions which people can rely on. In the USA, the 911 helpline is reliable, efficient, and top-of-mind for victims of an emergency. In India, the 108 number didn’t even answer our call! Could it be possible to recreate something like 911 within the private sector?

In the next sections, we will explore the contours and considerations of this proposed solution, which we will call ‘Safeline’.

Fun fact: Just three months after this, I also happened to witness a man collapse due to a heart attack in the Bangalore airport. Despite our location inside an international airport, it still took about 20 minutes for medical help to arrive. As we waited, the man’s friend attempted to perform CPR while frantically looking for help on Google. Emergencies like this happen all the time, and every time I hear of one, it always makes me think whether the existence of a service like this could positively affect the outcome.

The Solution

What needs to be solved for?

So in my mind, I have a fairly clear idea of what I think I needed at the time of my emergency:

A reliable and soothing operator: The first thing I needed in the emergency was for somebody to answer the phone! Knowing that you can call a trained human being who will answer on the first ring is a huge psychological relief that can’t be understated. Even if you are not sure that you are having an emergency, you still might need to speak to somebody who can reassure you and dispel your fears. The second thing I needed was for the person to calm me down. Panic is one of the most dangerous things in an emergency - a well-trained operator can help manage panic and change the atmosphere of an emergency.

Triage and first aid: The second thing I needed was for somebody to help me triage the situation. This can be accomplished through the establishment of a solid emergency response protocol. “Is the patient breathing, is his mouth open, does he have pain in his chest etc.”. After isolating the issue, I needed quick and simple first aid advice. Eg. “I have sent you a Whatsapp video showing you how to position the patient so that his airways are clear and he is no longer at risk of choking”.

Logistical support: The next dilemma I needed help with was what to do with the patient. Should we have taken him to a hospital or waited for an ambulance? How long would an ambulance have taken? Which of the 1000 ambulance services operating in Mumbai was the best option for me at that point in time? Could somebody call the ambulance on my behalf?

Each of the three categories represents a big problem I faced at the time of my emergency:

1) no reliable connection to a trained and helpful operator

2) no easy way of triaging the problem and taking life-saving action

3) no way of evaluating the different logistical options open to me

In my hypothetical solution Safeline, these problems provide the North Star for the service. So what does the service look like?

What are the features?

Human driven call center: In times of duress, I think people want to have an efficient and empathetic human being to turn to. For this reason, the Safeline offering would be built around a reliable and highly available call center staffed and run by human medics and operators.

Gold-standard care protocols and first aid material: The call center would need to be run according to quality care protocols. Operators would need to have emergency medicine training, a script of triage questions, and a protocol for dealing with different kinds of emergencies. The range of emergencies could include medical crises, fires, or safety issues like stalking or burglaries. The call center would possess a cache of images, videos, and other easily-digestible material that could be used in case of an emergency eg. a quick video guide on performing the Heimlich manoeuvre

WhatsApp-centric UI: Nobody wants to download a special app if they can avoid it, especially for something that is as rare as an emergency. On the other hand, WhatsApp is the most widely used app in the country, and it offers an easy way to deploy chatbots, exchange media, and make payments. It is also a perfectly discrete and intimate channel to begin building a brand impression with users.

Service aggregation: Justdial claims to have over 918 listings for ambulances in Mumbai city alone. Each vehicle will have a different feature set, route map, and mandate. If all of this information was verified and indexed properly, people could make much better decisions about where to seek care. All of this complexity can be stripped away at the call center or chatbot level in order to give the caller the most useful data.

Assisted service: In case of an emergency, the caller has a million things on his mind. With a clear operations protocol and technology backbone, dispatchers can simultaneously help with both treatment and logistics. While an emergency medicine doctor triages the problem and provides remote first aid, an operator can begin calling ambulances, alerting the patient’s emergency contacts, and sharing medical data with first responders (eg. equipment needed, medical history, allergies, blood type etc).

What are the challenges and difficulties?

Emergency care is a hard sell: A subscription-powered emergency care solution resembles an insurance policy in many ways. Just like insurance, you pay up front, and then reap the rewards of your payment in the future, if you even experience an emergency in the first place. Insurance is a notoriously difficult product to sell, because most people don’t see the need to cough up for it unless they have recently suffered some kind of loss. Human nature lulls us into thinking that we are indestructible.

Consequently, many companies in the emergency care space have found the demand side of the business to be the bottleneck. One example is Amber Health, a Delhi-based startup that provides a mobile app which users can download to find and order the nearest ambulance in case of an emergency. Amber allows users to pay for this service on the spot, and helps pass on the caller’s location and medical data to the ambulance driver and hospital.

The business had no shortage of supply-side partners - they partnered with around 200 hospitals across the country. As part of the deal, they provided a mobile app to the ambulance driver, turning the hospital’s regular ambulance fleet into a smart fleet which could be monitored and managed from a cloud-based portal. On the contrary, acquiring regular users and maintaining activity rates remains the more challenging obstacle.

While there is no obvious counterargument to this challenge, I wonder whether the demand side issues could be tackled through a combination of marketing and distribution hacks. Would life insurance companies pay for this service on behalf of their policyholders? Would schools, nursing homes, and corporations buy this en masse? Doctors receive dozens of emergency calls a week - could you pass them a commission to refer their patients? Would parents of young children and older parents make this purchase if you approached them at the right time with the right message?

On the topic of sending the right message, there is a company in Mumbai called Topsline that ran a number of campaigns 15 years ago about their new private emergency service. Their lavish physical advertising campaign - enlivened by the company’s brand new ambulances placed all over the city - allowed Topsline to sign up many families on 10-year subscriptions (including mine). So maybe the demand issue that Amber faces is more of a product and marketing issue rather than a customer interest issue. After all, downloading a standalone app and using it to book an ambulance does seem a little impractical.

In an emergency, people forget to call you

This is a very real problem. As a Topsline subscriber, I totally forgot to call them when I had these two emergencies. In fact, I don’t even know my Topsline membership number!

There are a few ways that a product like Safeline might circumvent this issue. One way would be to reconfigure the default emergency number on a user’s phone to the Safeline number.

Another way would be to request mic access and send alerts to the user when words like ambulance and emergency are mentioned. This is obviously an extremely intrusive way of accomplishing the objective, but if you don’t abuse the data and the user consents to it, then it might fly. I wonder whether it would be possible to bake this into Siri or Google Assistant.

In a similar vein, the Safeline backend could also be wired up to receive data from a customer’s wearables. If the accelerometer or gyrometer in a phone or smartwatch suggested the user had just experienced a sudden fall, stop, or unusual movement, the service could send a check-up message on the user.

Besides this, the other short term hacks I can think of revolve around SEO and digital advertising. Little ads that pop up when you search for emergency medical care that say things like ‘Call us now at 1234 to get the best emergency care anywhere in Mumbai’.

In the long term, a service like this would need to run on word of mouth and positive reviews in order to be sustainable. The goal would be to make the brand synonymous with the service - “call a Safeline”.

Out of sight, out of mind

One of the metaphorical devices used to assess the stickiness of consumer apps is the ‘toothbrush test’. Do you use a product at least twice a day? If yes, then you know the product is sticky and likely ripe for monetization.

On the other hand, if you only use a product once in a blue moon, the chances of building user engagement and revenue-generating patterns is slim. This is very much the case with an emergency service like Safeline.

One potential solution would be to allow users to set pill reminders which alert them when they need to take their daily medicine. This is something Amber attempted as a way of clearing the toothbrush test.

A well designed chatbot on Whatsapp could probably do pill, medication, and check-up reminders quite well. You could also use the Whatsapp channel to send users periodic warnings, offers, and other relevant information in order to stay top-of-mind. Here are some examples:

“Dengue sucks, but the monsoon always brings a rise in cases. In partnership with our favourite lab, we are offering a 20% discount on dengue vaccines. Order today to receive a vaccine in the comfort of your home!”

“Eating too many lychees can be deadly, make sure to enjoy these fruits in moderation. Speak to our chatbot to learn more! Reply with F to modulate the frequency of our daily trivia messages. Oh, and if you call us during an emergency, we will give you a higher chance of surviving lol”

“Did you know that there are emergency medicines which can help you in case of a heart attack or epileptic fit? Here is a video with a famous doctor who backs this up. Order these medicines using this link”

Medicolegal liability

This is a tricky topic. If a person dies after receiving treatment from your call center agent or ambulance provider partner, are you liable? Can a terms and conditions page protect you when it comes to life and death?

In extreme cases, mobs can vandalize hospitals if something goes wrong, so this is definitely an operational challenge to be wary of.

Lack of quality medical infrastructure and personnel

This is probably the single largest issue in this business, even bigger than the challenge of generating customer demand.

The quantities of skilled personnel and medical infrastructure like paramedics and ambulances are just too low for the size of the population, not to mention anything about the quality. At the higher end of the spectrum, we have incredible nurses, doctors, and hospitals. But as you go to the middle and lower end of the spectrum, there are wild fluctuations in quality.

This makes it extremely challenging for a business like Safeline that initially starts out as an asset-light aggregator of EMS services. Is it plausible to vet the quality of all the different vendors in a geography? After doing so, do you work with vendors who are of middling quality or stick to the few high-caliber operators? It seems like in a search for greater coverage, the company will have to compromise on quality.

Other companies in this space such as Stanplus have solved this problem by creating their own supply. They have an academy to train dispatchers, paramedics, and ER attendants. They also provide their own ambulances and equipment. The Stanplus model is to basically outsource the emergency function for partner hospitals, so that the hospitals don’t need to worry about setting up, staffing, or running their own call centers, ambulance fleets, or emergency rooms.

Because Stanplus works with multiple hospital partners, they are able to amortize their costs across these different players. Calls coming into the emergency rooms of partner hospitals get routed to the Stanplus hub, before the nearest Stanplus ambulance is dispatched to take the patient to the relevant hospital. By using the hospital partners for lead-gen, Stanplus solves the demand problem. By providing pooled resources to the network of partner hospitals, Stanplus solves the supply problem in a way that is more cost-efficient than a single hospital maintaining its own emergency assets.

There are also other models which could be used to bring supply onto the platform. In Israel, there is a non-profit community initiative called United Hatzalah, meaning “united rescue”. Essentially, medics volunteer to be a part of a network. Many of them receive special smartphones and motorcycles kitted out with certain medical gear - “ambucycles”.

When somebody calls in an emergency, the United Hatzalah backend alerts the nearest and most pertinent volunteers, who are able to weave through traffic on their bikes and arrive at the patient’s location faster than traditional ambulances. Here are some figures and statistics about United Hatzalah’s service:

6000 medics covering all of Israel

3 minutes average response time (time to reach patient after call) across Israel

90 seconds average response time in large cities

280 hours training for volunteers, who are given a free bike and phone as long as they keep attending to emergencies

600 volunteers in the Psychotrauma and Crisis Response unit (to provide psychological support to bystanders and victims of mental trauma)

800 ambucycles across Israel

Donor-led non-profit model

650K calls responded to in 2019 alone

This is a very interesting way of providing supply of paramedics and first responders. Perhaps the same model could be replicated with a for-profit angle. Maybe doctors and ER workers will accept a stipend in order to run part-time shifts on certain nights of the week.

In a different vein, supply can also be created through donations of emergency equipment to office buildings. Imagine a box containing a defibrillator and other first aid supplies lying in a highly visible office location. The box can feature a QR code so that bystanders can quickly figure out how to operate it. In addition to providing a supply of EMS equipment to high-density areas, this can also serve as a marketing strategy.

What are the tailwinds and headwinds for this idea?

Tailwinds:

Covid: The covid crisis has brought public health into the forefront of the popular imagination. It has also made telemedicine an accepted and indeed desirable part of the healthcare experience. As long as the pandemic lasts, you can imagine many people calling up a service like Safeline if you advertised the existence of a robust Covid care and support protocol.

Healthstack: The National Health Stack or NHS will be transformational for the health-tech industry. This is a really exciting and noteworthy topic, which I will revisit soon for a more detailed post. Through a component known as the Open Health Services Network (OHSN - pronounced ‘ocean’) , the NHS will enable seamless, interoperable telemedicine experiences even if the doctor is on one app and the patient is on another app. This means that patients using Safeline could at the click of the button conduct teleconsults with any doctor on, say, the Practo platform. The benefit of this architecture is that it decouples the demand and supply of telemedicine, allowing for richer, more diverse, and more specialized experiences rather than a 1-size-fits-all model which requires many competing firms to duplicate effort creating the market. So for example, an app can focus on building the best UX for doctors, and can just plug their supply of doctors into different popular partner apps which already have users (similar to how the OCEN platform approaches credit flow, described here in our September post).

Via a system known as the Personal Health Records (PHR) framework, the NHS will also allow individuals to discover, link, and share their health data across care providers. The gatekeeper of this system is an entity called a consent manager, responsible for helping users grant, manage, and revoke access to their data. Safeline could be a consent manager, which would give it more utility and stickiness. It could also act as a ‘health locker’, aggregating all of a patient’s historical health records for convenience and security. Lastly, Safeline could also consume the user’s health data across platforms so that it could provide more personalized service and assistance both during regular times and times of emergencies. There are a stackload of possibilities emerging from the rollout of the NHS, and this same tailwind will apply to thousands of other health-tech startups.

Wearables/IOT: Another tailwind for this business is the rise of IoT sensors and wearables. As described earlier on in this piece, gyrometers and accelerometers from phones or other devices can be used to infer possible falls, accidents, and other emergencies. Similarly, devices for women’s safety or elderly care which come with emergency buttons can be customized to make their first calls to a service like Safeline. Lastly, IoT-enabled sensors can send alerts to Safeline when the user’s biomarkers and vitals such as blood pressure and heart rate fall under a certain threshold.

Bundling and aggregation: One clever truism in the startup world is that there are only two business models: bundling and unbundling. To put it differently, there is value in taking a crowded solution space and stripping it down for clarity and performance. This is exactly the case in the EMS sector: there are literally thousands of service providers in a given city, but finding the right one at the right time can be very difficult without the help of technology and planning.

Fundamental human need for quality emergency care: Whatever else you may say about the business, health and safety is a fundamental human need. And solving fundamental needs well has to be valuable when done right. The present system in India has a LOT of room for improvement, so there are surely opportunities in this space for entrepreneurs to come in and elevate the standard of emergency care at scale.

Headwinds:

Free ambulance services: The CEO of a national hospital chain told me that in 2016, the chain decided to make its ambulance service free of charge. This was quite a radical move, as a 5km trip in an ambulance would sometimes cost upto Rs. 7000. The reason for this decision was twofold: to generate goodwill and bolster branding, but also to increase the size of the IPD funnel. Most of a hospital’s revenues come from the IPD or in-patient department (overnight patients). Many of the patients who contribute this IPD revenue first come into the hospital via the emergency room or ambulance. Therefore, the decision to offer free ambulance services actually resulted in ER and IPD growth for the chain. If other hospitals were to follow suit, consumers could find themselves with a multiplicity of free ambulance services. Having said that, identifying the right EMS provider and getting quality first aid over the phone in the critical early moments is still something that would be left unsolved for customers even if hospitals offered free ambulance rides. There are also opaque incentives at play for non-hospital attached ambulances: drivers often take money to ferry patients to certain hospitals, so the management of existing incentive structures and stakeholder groups is something that needs to be figured out.

High burnout and attrition rates for emergency workers: I’m not sure if this is a recent headwind as much as it is an extant operational hurdle, but it a big problem nonetheless. Responding to human emergencies on a regular basis can be exhausting and sometimes trauma-inducing. Especially so if the responder’s work is confined to a call center (a notoriously high-attrition workplace). How do you get people excited to work in a call center? And get them to stay there for more than a few months? I suspect the answer lies in great pay, working culture, and job benefits - but all of this is much easier said than done.

How big could this thing get?

Due to the demand-side issues discussed in the earlier sections, it is difficult to properly estimate the market size for a service like this. What we can do however, is draw some comparisons with real-world companies.

There is one private emergency service company which offers a subscription-based ambulance service. They also provide a network of medics and first responders who can arrive at the scene of an incident on motorbikes. All their operations are currently limited to one city, and the total number of vehicles they possess is ~100 (including cars and bikes).

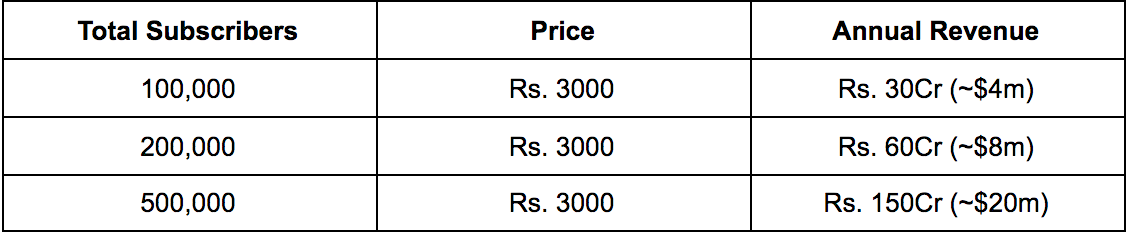

This service charges around Rs 3000 for a yearly subscription, and claims to work with hundreds of corporates. The combined number of subscribers they service through their B2B and B2C offerings extends ‘to the hundreds of thousands’.

This table illustrates the annual revenue figures for different subscriber bases at that price:

Is it feasible for a premium, for-profit, subscription-based emergency response service to capture 500K subscribers across the country? If the company described above can serve ‘lakhs’ of customers in just one city, I think it would be fair to assume that a competitor could expand upon that scale at a national level.

As for the unit economics involved, that would depend on the nature of services offered. If Safeline were to only offer a call center, with no physical supply network of its own, that would result in a very different set of numbers than if the company was to provide its own ambulances or ambucycles. I suspect that in both cases, it would be possible to run the business with decent margins, but I don’t know whether something like Safeline could be venture-investable.

The answer to that question would depend on the strategic decisions made by the team. Do you prioritize growth or margins? If you prioritize growth, what is your eventual moat? Where will be eventual profits come from? Can the model be replicated across geographies? Can you bootstrap supply into the network in a capital-efficient manner using financial engineering? The answers to these questions aren’t immediately clear to me - I don’t even know if any customers would pay for this to begin with! Which is partially the point of this post…

Moving on, besides the ‘core’ business of subscriptions, let us consider some other viable revenue streams. Some of the largest profit pools in healthcare are in pharmaceuticals and diagnostics. Pharma companies enjoy absurdly high margins, so white-labelling or cross-selling pharmaceutical products could be lucrative. Having said that, the unit prices for generic products are often low, so you need serious volumes in order to rack up high profits. In an allied vein, cross-promoting wellness tests and other diagnostic services is another way of unlocking commissions.

Overall, it is difficult to estimate the market size for something like this. If the service succeeded in genuinely increasing the safety and survival rates for subscribers, one could make the case that the user count could cross the million mark. After all, wouldn’t many middle class households pay a few thousand rupees a year to increase their family’s emergency-safety by even 10%?

On the other hand, there are many free and cheap health interventions that are widely understood today but rarely implemented. Smoking is an example - we all know it is bad, but we still do it anyway. To offer a more direct comparison, learning first aid online is free, but nobody bothers doing that.

Who else is doing this?

Amber Health: As discussed earlier, Amber Health has a fairly similar product. For all their innovation and supply-side success, it seems like they are running into the demand-side issue of getting enough customers to download and use their app. Amber employed a number of distribution and product strategies, so their journey begs the question of whether the market even wants this product in the first place. I have suspicions that the latent demand exists, but that the packaging of the service is key - I strongly believe that a human call center is the need of the hour during emergencies, and that the brand must appeal to people and find a way to stay relevant to their lives during the normal course of things.

Ziqitza, mUrgency: These companies attempted to aggregate ambulance access, but either shut down (in the case of mUrgency) or pivoted to serve governments by outsourcing their ambulance services (Ziqitza).

Ambee, Dial4242: Ambee was an ambulance aggregator based out of Hyderabad which managed to raise funding from Uber, amongst other investors. Judging by their cofounder’s LinkedIn profile, they seem to have shut down in 2019. Dial4242 claims to serve 150 cities with 4000 vehicles. Their website states that they have conducted 35,000 medical transportations. While this figure is nothing to sneeze at, it appears that higher scale has eluded them so far. The company’s Google Play store page has only 210 reviews in the last four years, although the reviews are largely positive. The Dial4242 value proposition seems very similar to Amber’s proposition: download the app, discover nearby ambulances, and book them through the app. Their SEO game is also strong, as they appear in many searches for ambulances.

Stanplus: As stated earlier, Stanplus is a B2B company that partners with hospitals in order to outsource their ambulance fleet and emergency service operations. They staff, train, and operate the emergency helplines of different hospitals, using a pooled set of state-of-the-art ambulances to serve emergency callers. They also provide the drivers and paramedics inside the ambulances. Because they pool these resources across hospitals, they are able to achieve higher operational efficiency. This allows hospitals to cut costs by shifting their operational hassles to Stanplus. The company is funded by Kalaari Capital, Pegasus FinInvest, and Insead Angels, and is presently on course to do $10m in annual revenue with most of its business coming from only Hyderabad. What I really like about Stanplus is that they completely own the infrastructure and personnel. This means that they are great supply-side partners for companies that aim to specialize in the consumer-facing demand side of things. I think the way they are building the business is both sustainable and commendable, and they have in fact implemented and monetized many of the things I have called for in Safeline; namely, the call center, care protocols, and dispatcher OS.

What would an MVP look like?

We have discussed fifty million different features and business models, but here are my thoughts on what this business should focus on building:

Highly available call center with trained operators and medics, with cellular telephony, VoIP, and video chat capabilities.

Gold standard care protocols, with professionally crafted manuals for triaging and treating the most common emergencies such as drowning, burns, bleeding, seizures, heart attacks, fainting, choking, strokes, fires, break-ins etc.

A dispatcher OS which includes a cache of specially prepared resources to send to customers in case of emergencies (such as instructional guides, videos) and a directory of care providers who the dispatcher can call on behalf of the patient.

A chatbot which can be customized by users to set their own pill reminders, booster shot reminders, emergency contacts, blood type, medical records, and more. The chatbot should also be able to provide first aid information taken from the manual.

Open Questions

Who would get access to care? My initial thinking was that only subscribers should get access to the call center, but that is complicated to enforce. What if the subscriber wants to call an ambulance for a friend who is unwell? What if the subscriber is unconscious and somebody else is calling on their behalf? There are many edge cases here that need to be figured out, but I am inclined towards some kind of freemium model wherein unregistered numbers can only call the call center once before being asked to pay.

Who pays for the ambulance and first aid? There are different ways to look at this - if the service has partnerships and integrations with hospitals, then it might be easier to pay the hospitals on a per-case basis and absorb that cost into the subscription fee. Another way to do it would be to inform the patient of the commercial terms and extract a commitment to pay before booking the ambulance at the operator level (to remove friction in the UX). Lastly, you could just send payment links to the customers before dispatching an ambulance, but I think this would be terrible UX for patients. I am leaning towards a cover-all subscription fee, basically like a pseudo-insurance policy.

Is subscription the only way to go? The alternative here would be to allow on-demand pricing, which works, but might also be a bit too much friction at the time of emergency, as discussed above.

Why go B2C, isn’t B2B better? It would appear that B2B business models in EMS are badly needed. The success enjoyed by Amber and Stanplus in partnering with hospitals proves that. I have also heard that hospital ERs really want technology that allows their resident emergency doctors to provide instant telemedicine and first aid in case of emergencies. While this is an interesting model, I feel like long sales cycles, low utilization, and small market size may be impediments to this route. The consumer-facing side of things is also frankly just sexier, and allows for the chance to build a memorable consumer brand, like Judy.co. But heaven knows that sexiness is not an indicator of success.

Conclusion

Although I have presented a lot of challenges and reasons why this kind of business is likely to be difficult to pull off, my intuition still suggests that a really valuable company can be built in the B2C EMS space.

And when I say valuable, I mean in terms of the value it can provide to people’s lives, more so than in valuation terms. While I think monetary success would likely follow from medical and psychological success, the question is whether enough people would discover and pay for a service like this for it to be a huge TAM business.

This is primarily because you are fighting against the part of human nature that doesn’t really care about contingency planning and disaster-mitigation in the absence of any disasters. I think that I have outlined some decent distribution strategies as workarounds to this, but there is room to go a lot deeper with those.

After contending with the demand and distribution problems, a product like Safeline would also have to prepare a strategy to ensure customer retention. This is also an area for much deeper ideation. I strongly favour a WhatsApp-based high-touch experience, but chatbots can be underwhelming when done badly so this needs to be fleshed out in more detail.

There are also question marks over the profitability of this business model. At first glance I think that the business could be run profitably. Your main costs outside of tech would be call center doctors and operators, and you might be able to serve many customers with a smaller headcount due to the infrequent nature of emergencies. However, if you begin to go deeper in the stack and offer your own human resources as a service (medics on ambucycles etc.) then you might get into lower-margin territory with much trickier ops.

Despite these real issues, I still do believe in the potential of this idea. But discounting the business prospects, which have the aforementioned blank spots, I find myself drawn back to this idea whenever I think of starting up or I hear about ‘missionary’ founders. I probably feel this way only because I experienced the problem firsthand, but I would love to hear what all of you have to say about it.

Would you pay for something like this? Would you invest in it? Is there a feature idea I missed out that should be included in Safeline? Please do leave your thoughts in this anonymous Google form.

Until next time, thank you for reading and take care!

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the following people for their insights and feedback:

Jayshree Kanther, Enzia VC. Pro-tip: Enzia is an exciting new early-stage health-tech fund to look out for!

Vedika Pinto

Avinash Jethwani

Seems like something a GoQii should do. They have the customer in. This makes their value prop very strong