When Content Meets Commerce: India’s Direct-To-Consumer Moment

Why we're entering the Golden Age (and Second Act) for consumer brands in India

*pulls up in time machine*

Greetings, friend. Hop in. You and me, we’re going to see what it was like growing up as a kid in India in the early 1980s.

*time machine gently lands at some point in 1982 Mumbai *

Picture this. The bell’s just rung to signal the end of the school day. The excited shrieks of children pouring out of the school gate are punctuated by the applause of Bata shoes on the ground.

You head straight to the baniya around the corner just like everybody else, hoping to spend a part of your precious pocket money on a Cadbury Five Star or (on an especially hot day like today) a bottle of sticky, sweet Parle Goldspot.

The agenda is the same every day. Head over to the maidan across the road and if you’re lucky, you can get in a few games of cricket before you’re summoned home.

You and your friends grab your Atlas Cycles and attempt to navigate the tetris of Hindustan Ambassadors and Bajaj Chetaks on the street to reach your destination.

This is your favourite part of the day. Where else would you rather be than playing cricket with your friends on a lazy Monday afternoon?

Your only concern (as always) is to avoid an ass kicking at home for ruining your school uniform. This, however, is a solvable problem. Liril soap for you, Washing Powder Nirma for your clothes. Both good as new.

See where I’m going with this?

It’s not like there’s anything better to do. Television is still in black and white. And government-owned broadcaster Doordarshan is the only game in town (fun fact: colour telecasts in India would only be introduced in time for us to host the Asian Games in November 1982). Aside from the 6 pm movie on Sunday - a religious experience for most people - the only thing on TV is a repetitive loop of the Bollywood music videos that were popular at the time.

You could pretend to be an adult and tune in to All India Radio (known as ‘Akashvani’ in those days) and listen to the biggest news stories of the day. Although after hearing the same headlines over and over and over again, this too gets old. Or you could pick up today’s edition of The Times of India which, since 1838, has been the oldest and most-widely circulated English newspaper in the country.

Yeah, the cricket field is probably your best bet.

OK thank you for the elaborate set up. Can you tell me why I’m here now?

What is uncommon about this time is just how common everyone’s daily lives were. Ask anyone who grew up during the 60s, 70s or 80s in India, and more often than not you’ll get the same answers to questions like:

What shoes did you wear?

What skin cream did you use?

What alcohol did you drink?

What was your favourite after-school snack?

You used the same butter, the same airline and the same bank. You had the same camera, the same TV and the same car. You even watched and listened to the same thing (at the same time!) and never complained about the dearth of entertainment options in your life (madness).

The brands people used tended to come from a combination of

- foreign companies that had settled in India either before Independence (Bata, HUL) or just after it (Cadbury, Nestle)

- legacy Indian business houses that had been born in the Swadeshi movement of the early 1900s (Godrej, Parle, ITC, Dabur, Amul)

- companies that had been set up by the British Crown to provide everyday products for their servicemen stationed in India (Britannia)

- and entrepreneurial ventures from Indian businessmen who had been quick to navigate the regulatory maze of the License Raj (Asian Paints, Pidilite, Bajaj Auto)

Because we were so early in our economic enlightenment, the brands that were first to the party ended up either inventing or becoming synonymous with a particular category. This allowed them to build up a strong base of customer loyalty and brand recall along with high visibility in local retailers.

Ah so that’s how India became a consumerist nation?

Well, the early successes of these companies put them in pole position to take advantage of the looming explosion of mass media communication in India.

The age of print advertising had kicked off during the Swadeshi movement in the early 1900s with the popularisation of the rotary Linotype machine i.e. the printing press, which was first used by The Statesman of Calcutta in 1907. This made it possible to print and distribute newspapers at scale in a cost effective manner.

Although advertisements had appeared in Indian newspapers as far back as the 18th century, they were mainly aimed at ‘informing’ the public of an event or occurrence (births, deaths, the arrival of ships etc), rather than trying to provoke a purchase through persuasive content.

Print ads for imported British goods began to make their way into Indian dailies in the late 1800s to promote the output of Britain’s own Industrial Revolution. The idea that Indian consumers could be convinced to buy products began to take hold, and in 1905 B. Dattaram set up India’s first ad agency in Mumbai.

Advertising had been legitimised as a profession. As the economy opened up and we moved further away from our socialist roots, brands started to appear more frequently in people’s daily lives - in magazines, buses, sports, billboards, and finally on colour TV in 1982.

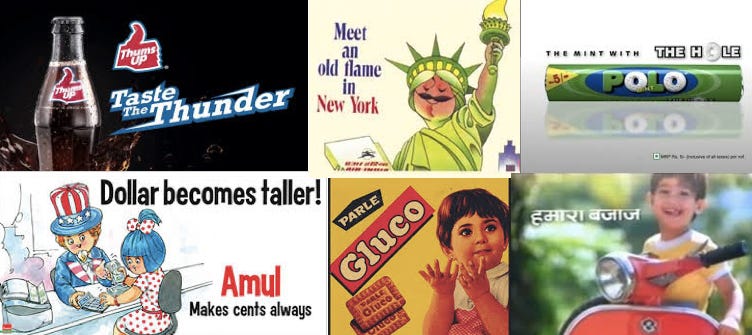

Gone were the days of hawkers calling out their wares in local markets. The biggest brands now paid the biggest fees to the biggest advertising agencies to book prime media slots and craft sophisticated marketing strategies. They muscled their way to the front of our psyches using clever taglines, catchy jingles and iconic characters.

These weren’t plucky Swadeshi underdogs anymore. They were established corporate behemoths that had mastered the art of brand building and storytelling.

The original heavyweights of liberalised India had made a fortune by creating homegrown commodities (and brands) for a post-Independence population. They realised that they could keep themselves at the head of the pack by dominating the growing number of new media channels at their disposal. By the end of the 90s, the same cast of established brands had marked their territory in every category by spending big on advertising on the TV and radio, in newspapers and magazines, and on the pixelated front pages of the early Internet. For an entire decade in the 1980s, the top 50 advertisers accounted for over 80% of total advertising spend in India.

Hell, even the advertisers were advertising.

So you had massive corporations with vast resources and economies of scale that could now use their control over the airwaves as a moat to ward off new competitors.

This era of consolidation is one of the reasons why India today is a land of hidden monopolies. Saurabh Mukherjea (Founder of Marcellus Investment Managers) wrote in January 2020 that:

“India is already an economy with extraordinary levels of profit share concentration in many key sectors. For example, in paints (Asian Paints, Berger Paints), premium cooking oil (Marico, Adani), biscuits (Britannia, Parle), hair oil (Marico, Bajaj Corp), infant milk powder (Nestle), cigarettes (ITC), adhesives (Pidilite), waterproofing (Pidilite again), trucks (Tata Motors, Ashok Leyland), small cars (Maruti, Hyundai) we already have one or two companies accounting for 80% of the profits generated in the sector. Now this trend looks likely to spread to more fragmented sectors where hitherto the unorganised players had greater profit share.”

So I assume that all of this is part of the ‘First Act’ for consumer brands in India (which is clearly a thing you just made up). What’s the Second Act? Something tells me the Internet has something to do with this…

Nailed it.

Marshall McLuhan famously said that ‘the medium is the message’, implying that the nature of a particular channel of communication had a far greater capacity to affect society than the contents of an individual message. He added that "Indeed, it is only too typical that the 'content' of any medium blinds us to the character of the medium."

What he meant was that we tend to underestimate the subtle structural shifts being provoked by a choice of media channel, mistakenly focusing on the information contained in a message rather than the vehicle that carries it.

Ok that makes no sense.

How about this. Before the Internet, we lived in a time of mass media. One-way media. One-to-many media. The ‘Loudspeaker Era’.

For a brand, the available advertising channels (TV, radio, newspapers, billboards) offered the ability to create a singular piece of content for a general audience. Sure, you could pick the type of newspaper or the specific TV channel, but for the most part you were shooting in the dark, hoping that this wide net of communication managed to snag your intended consumer.

The ability to broadcast one message for everyone meant that you were in essence also offering one product for everyone. If you recall how this essay began, this age of mass media resulted in a homogenised customer base made up of people that watched and bought the same things. As a result, brands didn’t optimise for individuality but rather for function.

Back in the day, the reason you bought Bata shoes was because you needed shoes and you knew that Bata sold shoes. Ask a millennial today why they use a particular skin cream and you might get 17 different answers ranging from ‘its the cheapest’ to ‘my favourite Youtuber uses the same one’ to ‘its because they plant a tree for every product sold’ or ‘because they only use organic woolly mammoth tusks' or ‘because they roast their aloe vera in the pits of Mordor’ or

Ok I get it, I get it.

Sorry.

Before the Internet democratised access to information, we lived in a time of information asymmetry. And in the fog of incomplete information, brands functioned as lighthouses of trust and security.

Because it was all one-way media where communication was done to us rather than with us, we didn’t really have an ability to independently separate market signal from market noise. So we deferred to brands.

The mainstream media functioned as gatekeepers of commerce. The most successful companies spent big on the best media slots to keep their brands at the top of public consciousness. As a consequence, consumers continued to trust the same recognised names, assuming that only a successful (i.e. quality) brand could afford to buy ads on TV and radio (the medium is the message). If you saw the same logo everywhere you looked and everywhere you shopped, you’d probably think it was legitimate too.

If you’ve ever wondered why the oldest business houses in India (the Tatas, Birlas, Mahindras etc) seem to have their fingers in a random assortment of major industries (with varying levels of success), it is in large part because of this fact. Once you had built an established brand in one sector you could leverage that trust to set up a completely unrelated business using the same brand name, and give yourself a decent chance of success. This gave the biggest companies a carousel of opportunities to provide whatever new product or service that was required in a liberalised India.

In India Unbound, Gurucharan Das writes:

So what’s changed?

The Internet is a cultural bulldozer that levelled a hundred different playing fields at the same time.

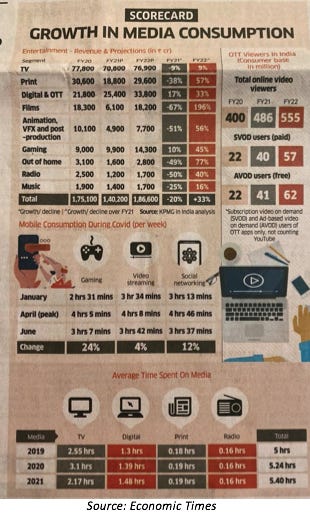

We now live in a time of information abundance. An individual no longer subscribes to the same diet of information and entertainment as everyone else. The internet has allowed for fragmentation and personalisation at the most minute level. The closest you’ll get to a unified cultural experience in India is the IPL (which is why brands are willing to pay a kings ransom to get in front of this captive audience).

Today you have complete control over where and how you spend your time. You can listen to podcasts on Spotify, scroll through Twitter or Tik Tok, watch the Premier League on Hotstar or a make-up tutorial on Youtube. Alternatively, you might enjoy reading newsletters on Substack or playing Ludo on your phone. The Internet is the greatest amusement park that ever existed - there’s literally something for everyone.

The diversification of our media consumption has led to the splintering of our buying patterns too. Just like we can choose from various forms of ‘micro media’ we can also choose from a number of ‘micro brands’ that have flooded in to cater to every niche requirement and personality type.

Scott Belsky writes in ‘Attack of the Micro Brands’ that “old and big brands are fighting against thousands of tiny brands with low overhead, high on design merchandise, and supremely efficient customer acquisition tactics. Many of us failed to recognize the collective impact of the long-tail of micro brands.”

The Internet allows you to cultivate the most specific version of yourself, and thousands of new brands are outgunning the old guard to help you do just that.

In order to differentiate themselves amongst an endless sea of competitors, modern brands are reworking their playbook for a fragmented media landscape. This new breed of digital-first brands have been so effective at carving out market share and attention for themselves that they now have a hip new name too - Digitally Native Vertical Brands or DNVBs.

If legacy brands were trying to solve for ‘what’ consumers wanted to buy, DNVB’s are trying to understand ‘why’ an individual is buying it.

Ok so if I understand correctly, you’re saying that because there’s no uniformity of media consumption anymore, people pursue their own individual interests online as opposed to thinking and acting in unison. And this means that there’s a window for new brands that can cater to individuals instead of the crowd?

Yup.

In the old world, commerce belonged to whoever had the resources to control the airwaves. That’s because they could use that control to relentlessly promote a singular product or message of their desire. But commerce is moving online. There is no ‘singular’ online. The Internet belongs to no one, and no two timelines look the same.

We increasingly do most of our internetting on social networks that have blurred the line between individuals and brands. You might have heard the pithy phrase ‘Instagram is where people become brands and Twitter is where brands become people’. That’s no joke. On your news feed there’s no difference between your friends, strangers, ads, brands, celebrities etc. Its all different flavours of the same thing.

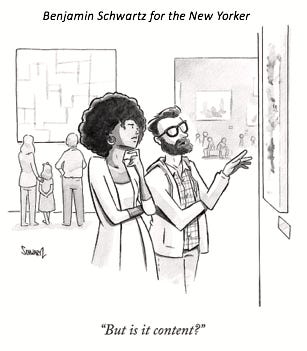

What is that ‘same thing’?

The Internet reduced all forms of media to its most basic form - content. This blog is content, a TV show is content, a Twitch stream is content, and yeah, your advertising collateral is content. You have 24 hours in a day and each one of your digital interfaces is trying to slice off a bit of your precious time for themselves.

Whether you’re David or Goliath, in this battlefield for attention, everyone starts at the same level. Legacy brands and modern brands are both just logos on a web page.

Social media platforms have enabled brands to come to life. Brands can now hone their own distinct voices in order to be heard in a crowded digital market. In an ideal world the coming together of consumer and brand should more closely resemble the coming together of a friendship based on common interests rather than a business transaction.

Thats why the DNVB playbook is to be more personal and personable, so they can blend into your life like a new friend and distract you for long enough so you don’t notice that your new digital friend is constantly trying to sell you a new mattress (or whatever). It's not devious, it’s just what millennials really want.

The quickest way to a millennial’s heart is through their content. Its not about just having the best product. Internet-first brands are now honing a distinct voice with a firm command over their individual media fiefdoms, giving themselves an edge over more established players in a time of information abundance.

2PM’s Web Smith coined the term Linear Commerce as the line at which content literally meets commerce. He writes that ‘the digital economy rewards the companies that work along the line that separates traditional digital media and traditional eCommerce. A great product needs an organic and impassioned audience. Captive audiences will need products and services tailored to their tastes. Linear commerce is the understanding that digital media and traditional online retail will eventually meet at the center – along the line – the most efficient path for growth.’

So in the bazaars of the attention economy, DNVB’s are merchants of content and commerce?

Yup, pretty much.

Media is the gateway drug to commerce.

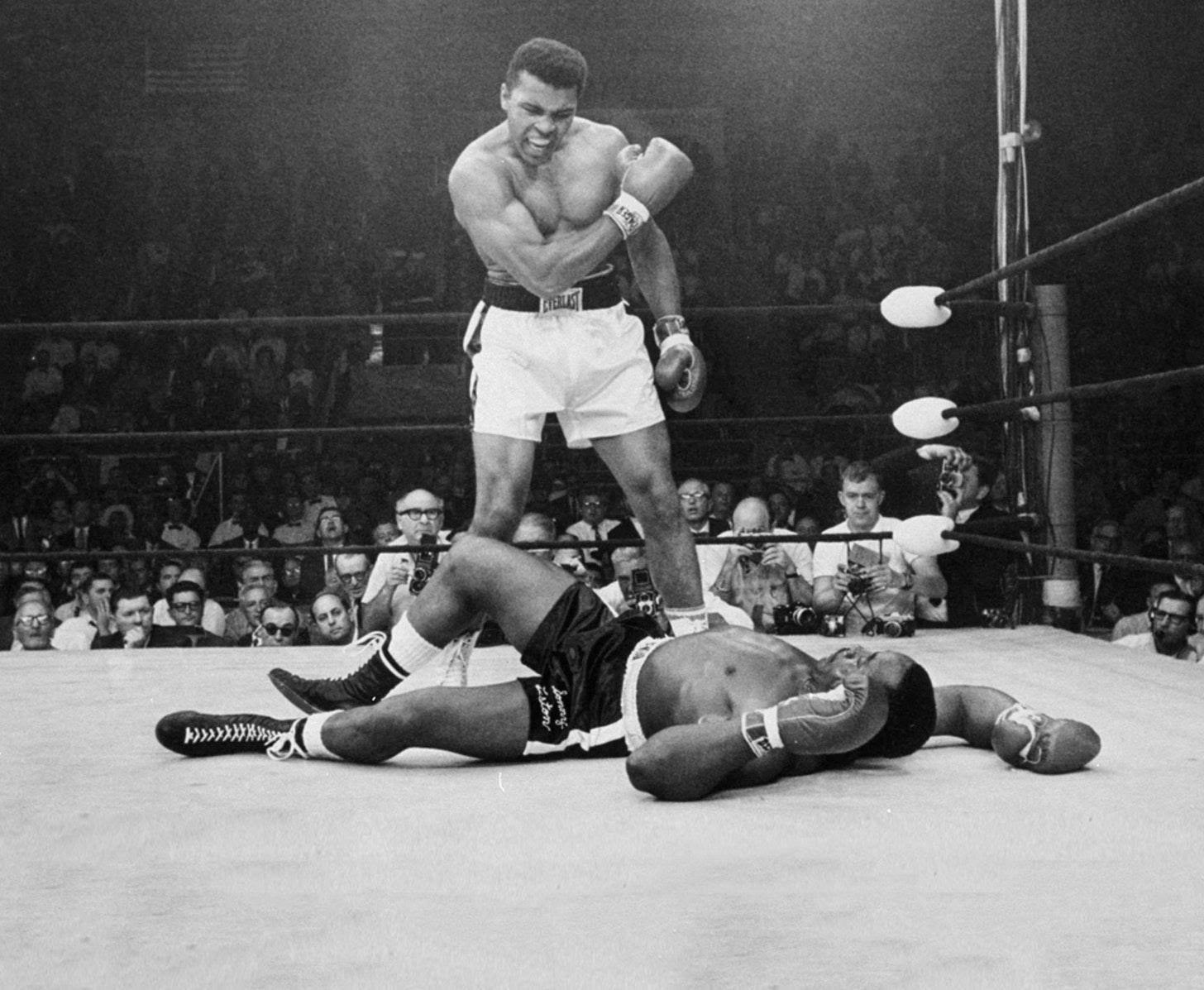

A successful strategy for commercial warfare today is not so much “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee” but “Act like a consumer brand, think like a media company.”

Hold up, I thought brands were ‘lighthouses of trust and security’? Legacy brands must surely play the same role online too?

Its not that brands themselves have changed but that the locus of authority has shifted from institutions to people.

With the fracturing of mass media, it is logical that people now also appoint their own preferred sources of authority on a product or service (Zomato reviews, twitter mentions, influencer recommendations, comparison websites etc).

A recent BCG report found that 86% of consumers check at least two data points before making a decision about FMCG brands.

There are so many different ways to validate the quality of a product that you don’t have to depend just on what companies tell you about their own products. Traditional brands no longer have a monopoly on credibility.

Gotcha. You still haven’t really said why this is ‘India’s Direct-To-Consumer Moment’?

Mark Twain once said that “History doesn't repeat itself but it often rhymes.”

The same way that enterprising Indians first rushed in to create basic commodities for a young India in the 1900s, we are seeing the start of a new era for consumer brands focused on catering to the needs and behaviours of a digital India.

These brands are known as Direct-To-Consumer (DTC) brands because they typically have direct influence over the end user experience (commonly on their own website or occasionally in their own retail stores), and in the case of DNVBs they also have control over each component of their supply chains.

There are now more than 500 DTC brands in India trying to make a name for themselves in every category. This year there are estimated to be over 330 mn digital buyers with an increasing number of online orders (50%) coming from outside of the eight biggest cities, even though our e-commerce penetration is still hovering in the single digits. This is still very early days but already there are signs that millennials who are ‘adulting’ for the first time have an appetite for new brands that understand their generation and push them towards a more aspirational lifestyle.

DTC entrepreneurs are creating new categories for the modern Indian, one who desires homegrown products that are world class and available at an affordable price. The flurry of new DTC brands that have attained a significant measure of success (and investment) reflects the changing tastes and lifestyles in India.

Tired of your Nescafe and filter coffee? Why not try a cold brew from Sleepy Owl?

Worried about your nutritional intake? Why not try multivitamin gummies from Setu?

Bored of Tabasco? You should switch to Naagin, ‘Home of the Original Indian Hot Sauce.’

Not getting enough sleep on the gadda? Order an orthopaedic memory foam mattress from Wakefit.

Old Monk not hitting the spot anymore? Try Stranger & Sons Gin with a splash of Svami tonic.

Concerned with the level of toxins in your skin care products? Mamaearth Co-founder Ghazal Alagh personally samples each batch produced by their factories every night.

Between the years 2012 and 2017, eight of India’s top 12 brands ceded nearly 0.4%-2% of either volume or market share to newer entrants in home care, packaged foods and beverages categories, according to research firm Euromonitor, and that trend is only poised to accelerate as DTC brands start tailoring their offerings to the most specific of niches.

A McKinsey study from earlier this year highlighted how 65% of consumers admitted to trying a new or alternate brand in the last year, with 10% of them claiming to have no intention of switching back.

Everything is up for grabs again courtesy of the Internet. Categories that had seemingly been closed are now being forced open by nimble entrepreneurs who understand that modern consumers are increasingly looking for the best deal and the best fit that can help them be the best version of themselves.

So you’re saying its worth starting a DTC brand? What else do I need to know?

According to data from Tracxn and Venture Intelligence, there were 60 online-first brands in India with over $5 million in revenue as of March 2020, more than 3x there were three years ago. The opportunity is all around you (literally).

Think about all the objects (re: commodities) that make up your life. The things in your room, bathroom, office and kitchen. The things you eat and use at a bar, restaurant or gym. If the name of a brand doesn’t immediately pop into your head then that’s a potential opportunity (some are obviously better bets than others).

Abhay Hanjura, co-founder of DTC meat and seafood brand Licious alluded to this in a recent interview, saying that “Four things in India are sold in black polythene bags - condoms, liquor, sanitary towels and meat.” This ‘branded butcher’ is now expected to hit Rs. 1000 cr in revenue by March 2021.

The important thing to remember is that no amount of cursive fonts, pretty packaging, and clever tweets is going to make up for poor unit economics. You’re still selling a product. And you’re likely going up against deep pocketed incumbents that have massive economies of scale, hyper optimised supply chains, and can buy themselves out of a sticky situation. You could get a lot of love by creating great content and building an engaged community. But if you don’t have your business hat on, chances are you won’t be in it for the long haul.

Your job is to find niches that are bigger than people might think (like meat consumption in India). Look for Goliaths, and build Davids. Its why traditional retailers refer to DTC products as pirahnas, because they are “growing rapidly in large categories by taking small bites out of the market share of leading consumer goods firms”.

Is it easy to start a DTC brand in India?

In short, yes. I’ll keep this simple:

- you have plug-and-play e-commerce software (Shopify, Magento, Woocommerce, Ecwid, BigCommerce, Volusion, Wix etc), online marketplaces (Amazon, Nykaa, Myntra etc) and logistics companies (Delhivery, Freight Tiger, Shiprocket, Locus etc) that make it convenient to set up an online store and easy to manage a complex supply chain.

- you have a growing population of smartphone users that are coming online for the first time, consuming content, and looking to diversify their consumption palate. Vernacular social platforms like Chingari, Sharechat, Suno India, Sim Sim, Lokal and others are aggregating unique segments of users. They are also facilitating the creation of a different breed of local celebrities and influencers that can function as proxy distributors for new DTC products.

- we have the most sophisticated payments infrastructure anywhere in the world that has extended the rails of digital payments to any Indian with a smartphone. Whether you know it or not, India’s approach to digital payments has been a huge equaliser for a population that is heterogenous in so many other ways. Customers from the smallest demographics will become customers for new DTC brands.

- if you make most of your sales on your own website, you have access to an incredible amount of market data. You can also maintain a direct relationship with your customers meaning that there’s a constant feedback loop for product ideas so you don’t have to guess what you users want. They’ll tell you themselves. Online kitchen and home appliance brand Lifelong surveys 500+ customers from all around the country each month, even providing ‘product demos and after-sales customer support in seven languages, over WhatsApp video and Zoom’. They’ve managed to gain the trust of customers by replicating the intimacy of a kirana store.

- With the right media strategy, it is possible to convert customers into a fans, fans into influencers, and influencers into a community using smart communication and content creation. You don’t need to spend big on advertising if your users think your content is so good that they keep voluntarily coming back to it anyway. Like how Sugar Cosmetics has an ongoing series of make up tutorials that regularly gets millions of views.

- VCs like Matrix Partners India, Fireside Ventures, Chiratae Ventures, A91 Partners, Sequoia Capital, Orios VP, 3one4 Capital, SAIF Partners and others have been active in funding consumer brands and helping them scale quickly both in India and internationally (if I’ve missed out your fund pls don’t hurt me).

Phew, what a trip. How do you see all this playing out?

A few random predictions for what we’re likely to see in the coming years:

1. Marketplaces will become DTC factories

Companies that currently offer a marketplace where they enable the consumption of third party products will serve as the greatest threat to established brands.

Think of what’s happening with Amazon, Flipkart, Big Basket, Nykaa and other e-commerce giants in India. Because they collect data on what consumers are buying on their platforms, nothing stops them from creating in-house private label brands for the most popular categories. This is a far more lucrative business than simply taking a cut of third party sales.

Online grocery delivery service Grofers says that in categories such as edible oils, ketchups, pasta and soups, and honey and spreads, the penetration of private labels increased by 157%, 83%, 59%, and 41%, respectively this year. The company hopes to improve the share of private labels by 20% over the next six months (it stands at 40% of total business currently).

Its why Swiggy has their own cloud kitchens competing with other restaurants on their app. Its even how Netflix decides what shows to make.

Even Times Internet (which owns India’s largest digital publications) decided in 2018 that it would create private label brands to sell across its lifestyle websites like MensXP, iDiva, Whats Hot and Indiatimes. It was betting that it could use the data about what their audience (40 million MAUs) enjoys reading and watching to get into e-commerce themselves, instead of just advertising the products of other fashion and lifestyle brands.

On a screen its logo vs logo, pixel vs pixel. It will become common for vertical marketplaces to enter the DTC game themselves and for ‘content marketplaces’ to try their hand at e-commerce. For DTC brands, platforms are not your friend. That’s why its important to have your own online storefront. Whoever does the best job of getting someone’s attention will also have the best chance of driving a purchase action. Which means…

2. Brands will start to function as media companies

If you create content and have a unique voice you’re essentially a media company.

There will be a shift from brands that realise that they are not interfacing with media anymore, they are media. A great product requires a captive audience and vice versa. Its one thing to manufacture a product, and another thing to manufacture demand for a product.

Restaurant aggregator and delivery company Zomato already has over 18 original shows and 2000 videos as part of ‘Zomato Originals’, an entirely new section for videos on its app. Zomato CEO Deepinder Goyal says that “We are constantly looking for new ways to engage our users around food. Most of our users visit our app several times a week. This presents us with an opportunity to further delight our users using Zomato Originals.”

Online jewellery store Melorra has a dedicated blog called ‘Now and How’ which functions as an in-house fashion magazine, featuring a range of lifestyle and outfit tips that incorporate (re:advertise) their selection of affordable, everyday jewellery. If Now and How becomes a leading fashion publisher in the eyes of a younger generation of women, then Melorra doesn’t need to spend anything to promote its products on other platforms.

The best DTC brands will become central sources of knowledge on their industries. Brands will pivot from churning out paint-by-numbers content to adopting the tactics of a full fledged media operation, which means they treat audience-building with the same seriousness that Netflix would.

Payments provider Stripe has an entire vertical devoted to publishing books called Stripe Press. VC stalwart Andreeson Horowitz has been one of the staunchest proponents of a full blown editorial strategy based around podcasts, newsletters and videos. Indian VC Blume Ventures even has a newsletter about podcasts! These are no accidents.

Its why India’s Pepper Content just picked up $4.2 million in Series A funding from Lightspeed India and others to build the world’s largest marketplace of content creators, media companies and enterprise buyers. Lightspeed’s Dev Khare wrote in his investment memo that ‘If software is eating the world, then content is consuming the world. Every company is now a content company’.

Quality content creation on a consistent basis is an opportunity to stand out from the crowd. Expect to see more DTC brands:

- start a podcast

- have a Chief Meme Officer or Editor-in-Chief

- create a newsletter (sometimes before they even have a product)

- hire a community manager

As the costs of performance marketing on Google and Facebook go up, even as the efficiency of ad spend goes down, the smartest brands will become their own publishers. Investing in editorial will be the new ‘pivot to video’.

3. Influencers and celebrities will drive local commerce

Maro Gabriele writes in Audience and Wealth that “Rather than buying from idols, consumers are increasingly buying from ‘friends,’ creators with whom close relationships are formed and maintained”.

Anyone can create content online, which means that the best individual (content) creators will also throw their hat in the ring to create the best products for their audiences.

In many ways the term ‘influencer’ has been reduce to a cultural pejorative. However in reality there are thousands of talented individuals in the most remote parts of India that are now cashing in on their ability to inform and entertain, at scale. In some cases these people are even better placed than celebrities to provoke purchase decisions because of the everyday familiarity that they have with their regular viewers/listeners/readers.

David Perell writes about how the Internet flipped the model of commerce around, meaning that instead of creating products and then finding an audience, today the Internet allows you to build ‘audience-first products’.

The influencers with the largest audiences are effectively living, breathing DTC brands. We’re going to see a shift from brand endorsements to brand creation courtesy of this growing population of creators who already have in-built distribution for future products. We’ve already seen this from traditional celebrities like Hrithik Roshan who leveraged his own personality to create the HRX fitness brand. Expect this to happen on a micro scale too.

Why? Because for an audience, buying these products is like buying into ‘a slice of their favourite influencer’s personality’.

Indian start ups are emerging to help supercharge the product-isation of influencers. EkAnek Networks recently raised Rs. 40 cr from Alpha Wave Incubation, Matrix Partners India, Sequoia Capital India and Lightspeed India to provide brand partners with a full stack solution to drive DTC operations, primarily centred around personalised content and local influencers.

SimSim announced it had raised $16 million in just seven months of its existence for its efforts to replicate the offline retail experience in the digital world with help from influencers.

Homegrown social media apps like MitronTV, Chingari and Roposo are tapping influencers on their platforms to enter the online commerce space in a bid to expand their revenue streams. Roposo expects ‘influencer commerce’ to be their second major category of monetisation after advertisements.

Bottom line - watch this space.

4. Digital Communities = Digital Commerce

Communities have replaced customers. If a DTC brand can endear themselves to a set of people who not only buy its products but also count themselves part of a selected group, then all bets are off. The goal is not to create a customer base but a set of fans who will always be along for the ride. If you can keep them engaged with quality content that is useful or entertaining, then you have a committed set of supporters that will even help you create and test products to solve their issues.

Matrix Partners’ Sanjot Malhi speaks of the importance of ‘owning’ your target group, saying that a successful DTC brand is one that can ‘sell ten things to one customer, not one thing to ten customers’.

In a time of low barriers to entry to start a DTC brand, a loyal community is as close as you’ll get to an impenetrable fortress.

boAt, a DTC brand which offers fashionable consumer electronics, calls their customers ‘boAtheads’. They’ve leveraged this ‘community of trendsetters’ around their products to race ahead of leaders like Bose, Xiaomi and JBL in just three years. In exchange for aligning their identities with the brand, boAtheads ‘get invites to online events, concerts and early access to product releases’.

In India, some of my favourite examples of digital community-building are Sheroes, Glamrs, CRED and Little Black Book (LBB) who are seamlessly bridging the line between content, community and commerce.

Sheroes founder Sairee Chahal has created India’s largest women-only community, which ‘is a safe and trusted space, where women can discuss various aspects of their life like health, careers, relationships and also share their life stories, achievements and moments.’ By building this digital sanctuary for women, Sheroes is poised to offer a range of products and services (DTC brands through sheroes.network, a fintech product called Sheroes Money) for an audience whose trust they don’t have to win. The Sheroes audience supports the Sheroes brand and vice versa.

Little Black Book (LBB) was initially created as a Tumblr blog by Suchita Salwan to document interesting places she had discovered in Delhi. It soon ballooned into a full fledged community of readers who were taking and making recommendations on local brands in cities all over India. Today this community has turned into a place where you can “come and discover, post, and transact with great local businesses. The core of LBB is you have these millions and millions of users who need to spend. They are interested in being interesting.”

David Perell calls this phenomenon ‘owned commerce’, where these media companies that are moonlighting as communities will be able to use their understanding of their audiences to offer a combination of engaging products and content that they can’t get anywhere else. Its the surest bet to building a successful DTC brand.

OK this is a lot to take in. Possible to give me a quick summary?

For you (who made it all the way here), of course.

India is moving from a time of mass media to a time of micro media because of the Internet

We are in a unique situation of being data-rich or content-rich before we are economically rich.

This means that our aspirations are increasingly global even if our economic abilities are yet to catch up.

The fragmentation of our media consumption has led to the individualisation of our brand preferences too

Today consumers have an unlimited choice of brands they can buy, but a limited amount of time.

We now make purchase decisions based on what brands best fit with our personalities and lifestyles

Software tools and online platforms have made it easy for anyone to start a DTC brand (but not everyone will succeed)

The line between content and commerce has blurred, and brands are in now competition with every other form of media for a slice of your attention

The best DTC brands will understand the importance of thinking like a media company and invest in editorial

Audience-building is the name of the game, and there are plenty of influencers, communities and celebrities that will create your next favourite DTC brand

I’m gonna need a few days to process all of this. Can you take me back to 2020 now?

Uhhh, I think this has been long enough. I’m going to just head straight to the references section, if you don’t mind.

Are you serious?

Further reading

Some fantastic work from writers that inspired this essay:

‘What The Hell Is Going On?’ by David Perell

‘Audience and Wealth’ by Mario Gabriele

‘2PM: The Study’ by Web Smith (and literally anything by Web Smith)

‘The Billion Dollar Blog’ by Nathan Barry

‘Welcome to the Roaring 20s’ by Brianne Kimmel

‘Cult Wars: The Making of a Cult Brand’ by Jordan Odinsky

‘Library vs Publication’ by Animalz

It took me a month to write this thing. If you made it all the way here and you thought this was a good use of your time, why not take a couple of seconds and share this post?

Or if you want to yell at me for wasting your time, you can find me on Twitter at @RahulSanghi1.

If you’re a media company or a DTC brand that wants to swap notes on any of this stuff, feel free to reach out at r.sanghi92@gmail.com

Tigerfeathers! is a DTC newsletter by Rahul Sanghi and Aaryaman Vir

Great read,Rahul!