Three Mangoes, Two Horns, and a Garage

A Tigerfeathers exclusive with Anupam Gupta (@b50) - longtime financial analyst, best-selling writer, award-winning podcaster, and author of a newly released book on 'The Rise of Asian Paints'

Hey folks👋

Welcome to the 248 new Tigerfeathers subscribers who’ve joined since our last piece.

At last count we’d qualify as the 7th smallest country in the world, on course to break into the bottom 20 by the end of next year. Click here to submit your application to the first ever Tigerfeathers national volleyball team👇

This edition of Tigerfeathers is brought to you by…Navana.AI

Navana.ai has been at the forefront of revolutionising digital access in India since 2018. They’ve been steadily working at the intersection of AI and voice-based interfaces to craft digital experiences that can be accessed by the majority of Indians that don’t speak English.

Their flagship platform, Bodhi, is a high-performance speech recognition API supporting over 11 languages and 40+ dialects, including Hindi, Tamil, Marathi, Bengali, Kannada, Telugu, Odia, Maithili, Magahi, Bhojpuri, and Chhattisgarhi.

Bodhi's standout transcription accuracy and speed make it possible to:

- automate real time conversations in 11 Indian languages

- build AI contact centres

- do real-time translation and subtitling

- offer agent assistance support

- derive intelligence from call centre recordings

- and more

Want to try it for yourself? Check out a live demo here👇

“If you wanted to tell the story of 20th century India through the story of a single company - it would be Asian Paints.”

A bit of a winding background to this one.

Back in early 2018, I moved back to Mumbai after five years of living and working in the UK (mainly because I hadn’t seen the sun since 2013). My first stop in the Indian tech ecosystem was with a startup named Koinex, which, for a good chunk of time was India’s largest cryptocurrency exchange.

In April 2018, the RBI imposed a ban on regulated financial institutions from working with the crypto sector, which meant that banks in India refused to do business with us (till the ban was overturned by the Supreme Court in 2020). At the time, there was a bunch of misinformation about the Indian crypto market. So we decided to set up a ‘media arm’ called The First Block, to help the steer the local crypto narrative in a more productive direction.

This included a podcast - also called The First Block, which we started in the back of our snack room at the office.

Our goal with the podcast was to find a balance between guests that were from the crypto world, along with people outside of crypto that might have an interesting perspective on either the economics, the psychology, or the philosophy of tokenised finance. The first episode featured my partner and co-founder at Tigerfeathers:

From our shitty little set up, we managed to put together a pretty solid line up of speakers over the next few months that included several of India’s leading crypto founders, the Chief Strategy Officer of the Human Rights Foundation, famous Internet writers and authors, the Director of the World Economic Forum’s Centre for the Fourth Industrial Revolution, and former Olympian and MMA world champion Ben Askren (a few weeks before he would find himself on the wrong end of the fastest knockout in UFC history).

By far our most popular episode at the time was with Morgan Housel, who would later go on to write The Psychology of Money and Same As Ever, two of the best selling books of all time. We put out a bunch of promos ahead of the episode, advertising it as Morgan Housel’s first appearance on any Indian media platform…till we had to delete all of it when we realised he’d done a brief stop on another one-year old podcast called Paisa Vaisa, hosted by longtime financial analyst and investment advisor Anupam Gupta, as part of India’s then-nascent IVM podcast network.

That podcast - Paisa Vaisa - is now one of the longest running podcasts in India (with over 4 million downloads). It has since become the leading personal finance podcast in the country, going on to be selected as the ‘Best Business Podcast’ at the Asia Podcast Awards in 2019. Anupam himself went on to write two books - The Wisest Owl and The Victory Project (co-written with Saurabh Mukherjea), the latter of which would become a national bestseller.

We eventually killed our own podcast after we shuttered the crypto exchange in July 2019, pivoting into a new company called Flobiz that builds software tools for small businesses. The RSS feed of the podcast still exists (so you can find it on all the usual audio platforms) but The First Block’s domain was eventually taken over by an…adult entertainment website (yes) (pls don’t try to find it).

Why is any of this relevant?

Because a few weeks ago I saw this post from Saurabh Mukherjea (Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Marcellus Investment Advisors), about the launch of Anupam’s new book:

It’s about the story of India’s largest paints company - Asian Paints - and its visionary leader - Champaklal Choksey.

I didn’t know anything about Asian Paints, Champaklal Choksey, or the paints industry. But I’ve been listening to Anupam’s podcast over the years, so I ordered the book, and spent the last few weeks getting up to speed with, uh, the paints scene in India. I was surprised to learn that:

Asian Paints was started in a garage in Bombay in 1942, in the same year that Mahatma Gandhi launched the Quit India Movement

It was started by four original founders, who took advantage of the ban on imports imposed by the British during World War 2 to set up a local paints manufacturing facility in India

It became the largest paints company in India in 1967, and still retains that position 57 years later

It was one of the first organisations in India to radically alter their commercial operations around the use of a (mainframe) computer, well before even the likes of ISRO had access to their own device.

It was one of the first commodity companies in India to successfully make the transition to becoming a consumer brand, heavily leveraging the new canvas of colour TV when it was introduced in India in 1982

It has given public investors the highest compounded returns in the history of the Indian stock market, with a Compounded Annual Growth Rate of 28% over the 42 years since it went public in 1982

It felt like a story more people should know. It also felt like a very Tigerfeathers story. So I did the next best thing and sent Anupam a cold email asking if he would be open to sitting down (or standing up) for a interview that would be transcribed for the Tigerfeathers community.

He was kind enough to give me 90 minutes of his time this past Monday. We talked about what made Asian Paints such a compelling subject to cover; the untold legacy of its talisman founder - Champaklal Choksey; the process of writing the book; the business and evolution of podcasting in India; whether he would rather have the ability to teleport or fly; and much more. What follows is something between an interview, an essay, and a serialisation of Anupam’s book.

One last thing before we get there - I’m currently working on two separate essays that I’m hoping to publish in the latter half of this year. The first is about the dissolution of language barriers in the age of AI, and the second is about the opportunity to build intellectual property out of India over the coming decade. If you have a particular interest or investment in either of these areas and you’re open to sharing your insights, feel free to get in touch by replying to this email or dropping me a DM on Twitter.

Without any further distractions, here’s our exclusive sit down with Anupam Gupta. Enjoy!

‘Happily the times we live in have opportunities aplenty’

- via Champaklal Choksey’s last ever letter to Asian Paints shareholders (FY 1996-97)

To start off, I want to set the table for our readers who don’t know anything about Asian Paints or the paints industry. To make it a little interesting – let’s say you were on Shark Tank and you were introducing the company - what would you say about the history, the products, the market position or the DNA of Asian Paints that would make the judges sit up and pay attention?

Okay, think of a company that has five seemingly disparate facets about it that are simultaneously true at the same time. Out of 5000+ publicly listed companies in India, not a single one has all five. There are companies that have one or two of these attributes - maybe even three - but not all five.

It is a Nifty company - which means it’s reached significant size and scale

It’s grown each and every year since it started (in revenue terms)

It’s been number one in its industry since 1967 - a position it has not relinquished, at all, till now, ever - which is probably the longest any business in India has stayed at the top of their sector. If you look at India’s corporate history, most leading brands have churned. Premier Motors with Fiat couldn’t hold on. Bajaj Auto, Airtel - same story. Any industry that has survived in free competition in India has seen a churn in its top players. Asian Paints hasn’t seen that, yet. Maybe it will going forward, but that hasn’t happened so far.

It’s a family-owned business - not the family of a single promoter but of four unrelated families (two are technically related but it’s not an immediate relation). In any case, not enough has been written about the uniqueness of the family-business construct in India. This one is even more unconventional.

Lastly, it is professionally run. It is as professional as you can get, in that it has been a premium destination for the brightest MBAs in India right from the 1960s.

So these five things, all taken together, are what make it unique as a subject of study.

A logical follow on from that answer. So we’ve been running this newsletter for four years. I’d say we have two general yardsticks that we use to measure the success of anything we publish - 1. Is it something we would enjoy reading ourselves? and 2. Were we able to successfully convey why we thought a certain topic was cool? i.e. were we able to translate our own curiosity and excitement for our readers so they understand why we invested so much time writing about a company, or a policy, or a piece of tech, and they also understand why its worth investing the time to read that article.

I’ll turn this second question back to you. Why did you think this story was worth covering? Why did you invest the time to write it, why should people invest the time to read it?

Two words - honesty and scale. Both typically don’t go together in India. At some point, one is usually sacrificed in service of the other. But not in this case.

I’ll give you a little background about the genesis of this book. It goes back to 2016 when Saurabh Mukherjea [the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Marcellus Investment Managers] published his book The Unusual Billionaires. The premise of the book was simple - it would feature the stories of those companies in India that had seen 10% revenue growth and 15% return on capital employed every year for the preceding decade. Just two filters - that’s it. He didn’t want to just use market cap when compiling a list of extraordinary Indian companies because market cap is the result, not the cause, of exceptional performance over time.

What he found was that over 99% of public companies in India had failed to hit that marker. But Asian Paints was one that did. It was one of the seven companies whose case studies made it onto the book. The others were Astral Poly, Berger Paints, Marico, Page Industries, HDFC Bank and Axis Bank.

The book was published in 2016. Asian Paints had joined the SENSEX only in 2015, which was when the wider investing public really became aware of its story. When Saurabh was researching the Asian Paints story for the book, he became aware of this almost mythical figure - Champaklal Choksey, who had been one of the four original founders of the company. As he interviewed ex-employees for his book, again and again the same name would come up. The old timers at Asian Paints - people who’d been there for many decades - all said that although there had been four original promoters, the success and endurance of the company owed a particular debt to Champakbhai [as he was endearingly known].

So he started to dig further. He was curious why - although people had heard of the Tatas, Birlas, Goenkas and Ambanis - in India no one seemed to have heard of Champaklal Choksey, even though he had built a highly successful Indian company that had thrived for over 80 years. His name never came up in conversations about successful business families in India.

I remember having a conversation with Saurabh at the time where we were trying to rationalise why this was the case. We realised that, for one, Champakbhai had passed away in 1997, after 55 years of running the company (and fatefully passed away on the same day he sold his shares in Asian Paints). That the company continued to grow and progress after his death was a credit to the institution he had built. And two, I remember telling Saurabh that half of India’s current population had been born after 1995. That’s not opinion, that’s fact. Forget corporate history they barely know Indian history before then. It made sense that no one had heard of Champakbhai’s story.

So the idea for a book about Champaklal Choksey and Asian Paints entered his head. Saurabh reached out to the Choksey family to see if they would collaborate with him for the story. Like many business families in India, particularly from that generation, they were initially reluctant. They didn’t want the limelight - which I completely understand. In India if you talk about your business successes you attract a lot of unnecessary attention, some jealousy, some suspicious eyes from even your family and friends. Plus, they had already sold their stake in the company in 1997 - so from their perspective there really wasn’t much more to say.

But after much convincing and cajoling, in 2022 Saurabh finally managed to break through to them. They said ‘let’s do it’. So he called me up and asked if I was interested in taking the reigns. I was like “Are you kidding me?? You don’t have to ask twice.” Although Champakbhai’s family wouldn’t officially commission the book, they were gracious enough to make themselves available for several interviews, and didn’t place any guardrails on what I could write.

I told Saurabh then that this would take a while, which he was okay with. Now when I look back - it’s taken two years. It’s been two serious years of working on this book. That’s how it exists. ‘Why’ it exists is because of the two reasons I outlined at the start of my answer - because of honesty and scale. And because of the untold story of an entrepreneur and an Indian that nobody seems to know. Champakbhai’s story should be written next to the likes of Rahul Bajaj, as a visionary industrialist who built something of incredible size and impact, as someone who made a meaningful contribution to the country, and to the prosperity of so many of its citizens. His story deserved to be told.

I’d love if you could take us back to the start of Asian Paints. I was surprised to learn that India has its own version of the romantic ‘startup in a garage’ origin story similar to the likes of Apple, Microsoft and other fabled companies from the West. How did these four guys - none of whom had any specific training or education in the manufacturing of paints - find themselves at the helm of this future behemoth?

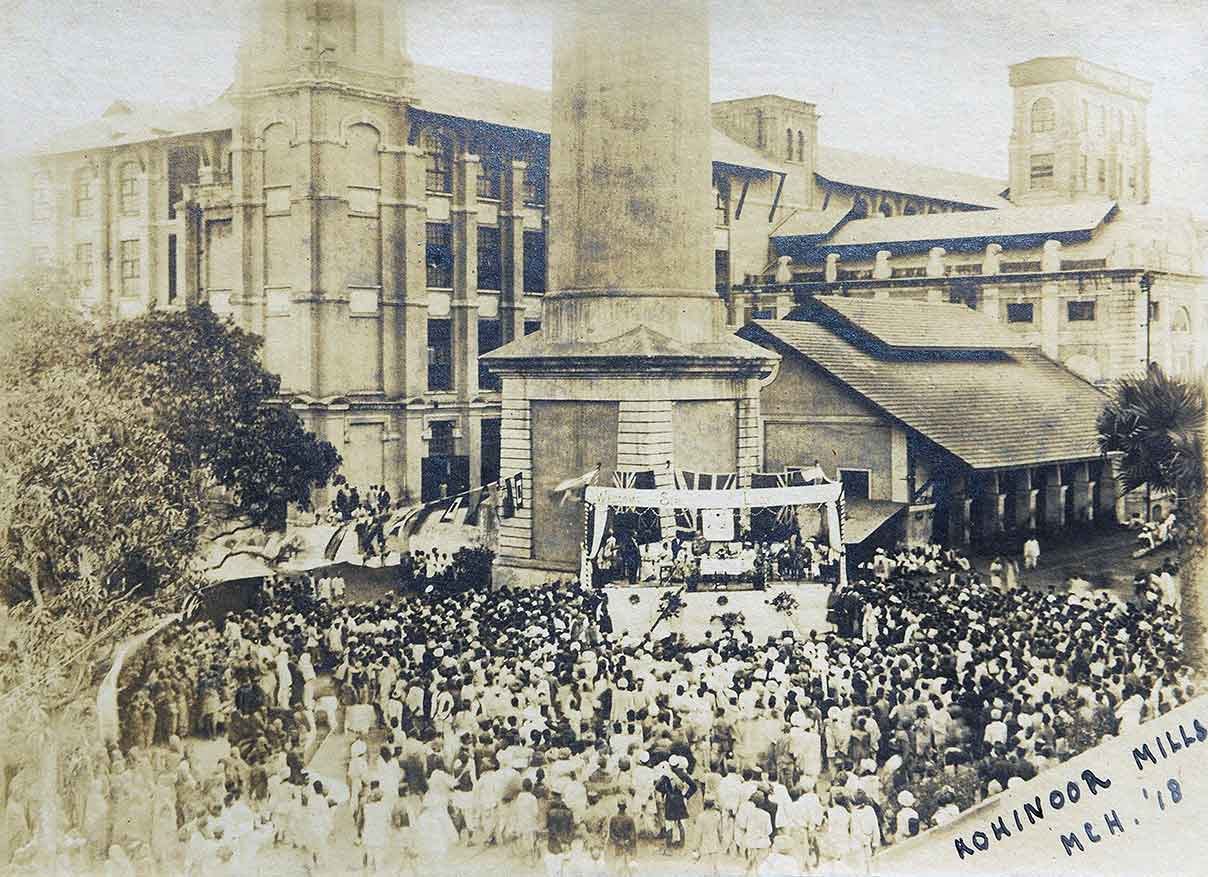

The Asian Paints story starts in the early 1900s. Champakbhai himself was born in Bombay in 1917. He had begun work as a cotton ‘jobber’ in his 20s [Bombay’s cotton industry had boomed on the back of the American Civil War in the late 19th century, which had curtailed the export of cotton from the American South, increasing the prominence of Indian cotton in the global market. A jobber was essentially a personnel manager that filled in a number of important roles at a cotton mill].

Champakbhai was introduced to Suryakant Dani through a common friend around this time. Suryakantbhai and him were the same age, and quickly became fast friends. The former was working at a pharmacy at the time when he was offered the chance to set up a paints trading agency by a local manufacturer. Eventually he and Champakbhai would start that agency - the Neptune Trading Agency - together as partners in 1939.

At this time the British had banned the import of paints (and other products) at the onset of World War 2, which led to a great demand for local paint manufacturing in India. In Bombay in particular, there were constantly ships coming in that needing repainting, specifically for anti-corrosive paints that rustproofed the parts of ships made of iron and steel.

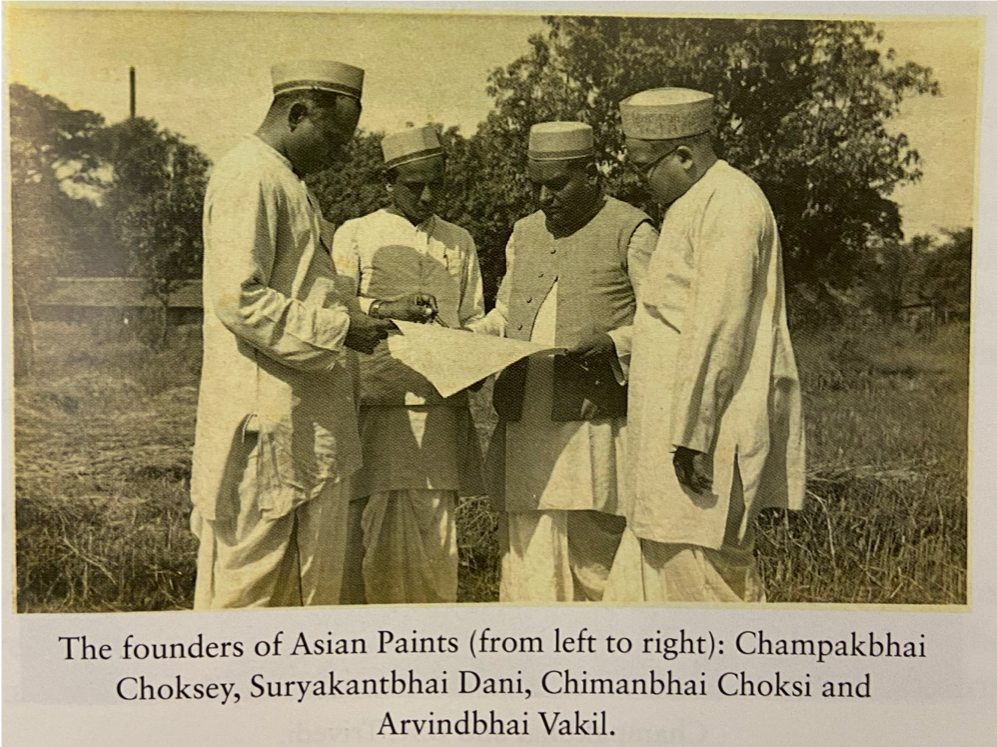

Neptune Trading quickly became successful, largely due to the expertise of the duo to find shopkeepers, and turn them into loyal customers. They eventually realised that the paints they were tasked with selling were of a poor quality. Given the intensity of the demand in the market, they decided to start their own manufacturing facility to make paints themselves. They were joined by two more partners - Chimanlal Choksi and Arvind Vakil (who was Suryakant Dani’s brother-in-law) to fund their venture. In November 1942, in a rented garage in Bombay, that’s when the Asian Oil and Paint Company was born.

What is remarkable about this story is that these were four simple guys from conservative Gujaratis families. Their company was born out of being at the right place at the right time, and being confronted by the right opportunity. There was no sense of ‘do what you love’ here. There was no ‘passion’ for paints. For them it was ‘you wake up in the morning, you have to go to work, you earn your salary and you come home’. It was necessity, and a desire to work hard to support themselves and their families that led them to this business.

They weren’t even highly educated. To make paint you actually need to be an engineer, or actually know the process. These are four guys that didn’t know anything about that. They only knew how to sell paint. Out of these four, only Champakbhai could speak English fluently. They set up a rag tag ‘production facility’ in one of the by-lanes in the central districts of Mumbai. And they began making paints, physically pounding the raw materials, pigments, and oils to make primary colours, and created other colours by mixing these together. They would sell these paints door to door.

What a lot of people don’t know is that there was a fifth partner who came in and contributed his capital - Jamnadas Vora. At one point he became the largest shareholder of Asian Paints, but he had to sell his stake early because of some family compulsions. Anyway, thats the story. These people got into the business out of chance. They saw the business grow. They secured more capital. And then they took off.

You alluded to the World War aspect, that they started up during the World War 2 ban on imports. It speaks to how intertwined the Asian Paints story is with India’s own story in the 1900s. That was probably my favourite part of your book too.

I suspect that I’m not alone in that I graduated from school with somewhere between a disdain and a disinterest in history, and I think that’s because we’re badly shortchanged by how the subject is taught in classrooms. In the pandemic I started reading a lot of Indian economic history, and I realised that I had this giant blind spot with regards to the evolution of post-Independence India.

I think learning about the stories of the oldest companies in the country are the best way plug that gap. For Indian companies in particular - because capitalism is a relatively new construct here - the stories of our oldest businesses aren’t just economic stories, usually they’re also windows into a specific time. Asian Paints is literally older than the country. They’ve straddled so many of the most pivotal episodes of 20th century India - the World Wars, Independence, the inauguration of IITs and IIMs, the arrival of computers, the arrival of colour television etc. What can you say about Asian Paints as an entity that surfed the wave of India’s own evolution in the 1900s?

It’s exactly what you mentioned. It’s almost like they had the foresight to predict these developments and imbibe them into their corporate trajectory. Let’s start with World War 1 and World War 2. Bombay in the late 1800s had gotten a boost after the American Civil War, specifically our cotton industry. Three things came in, in that period - electricity, trains, and markets.

So all these three were in place when Asian Paints started. As someone starting a business at that time, that is an incredible tailwind to have. If you’re an entrepreneur, if you’re seeing these things happen, why wouldn’t you take advantage of that?

You’ve got the cotton market where Champakbhai was working. You’ve got the entire foreign paints industry which was already there. Electricity is coming and you can literally see progress happening. That’s how it started. From there they just surfed each new wave:

Engineering institutes were set up - they hired chemists from there.

Management institutes were launched - they hired professional MBAs from there.

Computers arrived in India - they bought a mainframe computer to start forecasting demand.

Television became ubiquitous as a medium - they used it to spread their message and build their brand.

It’s like they had a crystal ball. Not only did they see these changes coming, but they were bold enough to take a huge gamble on them. That’s where this becomes even more counterintuitive. This was a family business. These are conservative Gujaratis who usually don’t take big, risky, unconventional bets - certainly not at that time. But this was a different time. For people that weren’t educated, you didn’t have many options. There weren’t many fancy jobs to go around. What else were they going to do? 80% of the prior generation went into entrepreneurship because they had no choice but to set up their own shop, and do whatever they could to make it successful.

At every stage, these guys pushed themselves to go bigger. They moved onto a bigger production facility in Matunga, and then to a factory on a huge piece of land in Bhandup. They expanded outside of Mumbai, then outside of Maharashtra, then outside of Western India. They could have stopped at any point, and decide to just chill. I don’t know why they didn’t, but they didn’t. Taking these seemingly calculated and concentrated bets at specific points of time, they rode the waves presented by the changing tides of 20th century India.

You had this section about the paints business at the end in your appendix that I really liked. It helped to contextualise their achievements for me. I’d love if you could talk about what makes paints such a unique business?

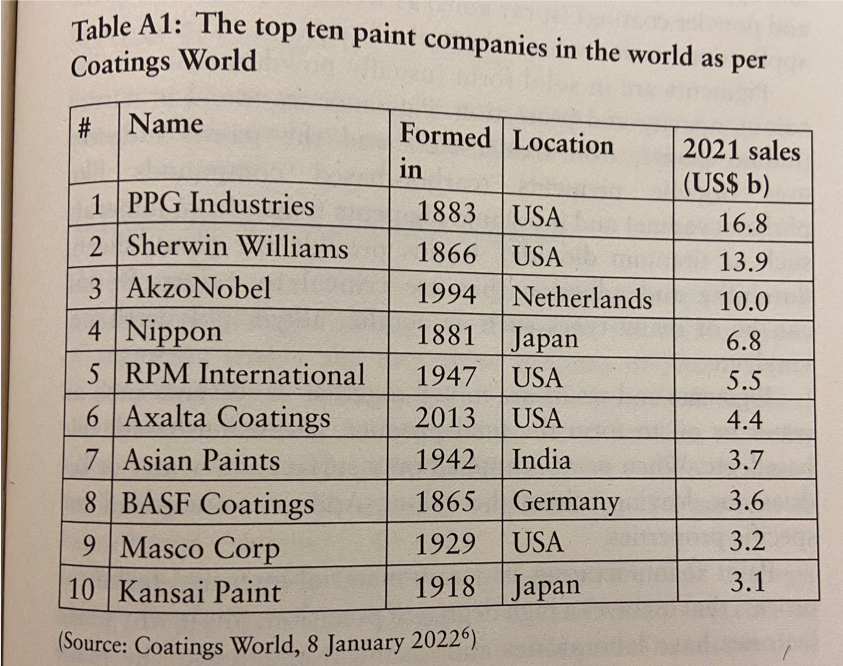

Paints have existed as long as colours have existed. The first paints were those invented by cavemen to decorate their cave walls (whatever origin story of humanity you choose to believe). That’s why the paints industry around the world also has some of the oldest companies in the world.

Paints have two main functions when applied to surfaces - decoration and protection. And two main segments - industrial and decorative. In the early 1900s most of the paint sector was working on industrial use cases - painting of ships, for example. Today that would include the painting of automobiles, consumer durables, public utilities etc. But as consumerisation picked up in the 20th century, the main arena of battle shifted to decorative - that’s where Asian Paints thrived. This now includes things like interior and exterior wall painting, waterproofing, wood finishes, enamels, undercoats, etc.

The challenge with paints is that, on the face of it, there’s very little room for differentiation. Yellow is yellow, at the end of the day. From the demand side - that’s what makes it different from other consumer goods. Other consumer products - colour TVs, motorcycles, cars - eventually when they become successful they typically have strong differentiators. Paints don’t really have the same delineation.

And in India, on the supply side, till tinting machines [more on this later] came in in the 90s, paints was an extremely difficult product for a dealer [i.e. a retailer] to invest in.

It requires a large amount of space to set up a paints shop

It requires a large investment to keep every colour that a consumer might want

You have to replenish the most popular colours very often

So it’s tricky to get it right.

Another thing I hadn’t realised, was how much the paints industry is a bellwether for the broader economy.

I mean it’s logical, right? Leave aside the industrial segment, which has many different drivers. But on the consumer side, where does demand come from? It comes from:

people renovating their old houses

people doing up their new houses

Both are indicators that people are generally doing well. From that perspective paint is closer to a consumer staple like soap, than it is to a discretionary purchase. Because if you’re in a situation where you need to paint your house, it’s unlikely that you can put it off (unless you’re in a position that genuinely won’t allow it).

When demand for paints is down, it generally means times are tough. If new houses aren’t being built (even though India is starved of housing), if people aren’t getting their basic housing needs satisfied, then something is wrong.

You can push back buying a car, or maybe even push back buying a two-wheeler. But if your house is crumbling, or you’re moving into a new place, you will likely have to buy paint. From that perspective both soap and paint are linked to the satisfaction of basic human needs.

You mentioned a little while ago that ‘yellow is yellow’. I got this point from a friend who works in an investment group that looks at public equities - he said that because paints as a product can never display the brand of the company (i.e. if you look at the wall in someone’s house it won’t have a logo on it), the competitive advantage for a paints company needs to be derived at the back end i.e. in the supply chain. Asian Paints is apparently the perfect example of this. What did they do to nurture these behind-the-scenes advantages?

The term ‘supply chain’ didn’t even exist when they started! They had to figure all this out themselves. You could distill the answer to your question down to two broad reasons - an investment in people, and an investment in technology.

1. From the people side -

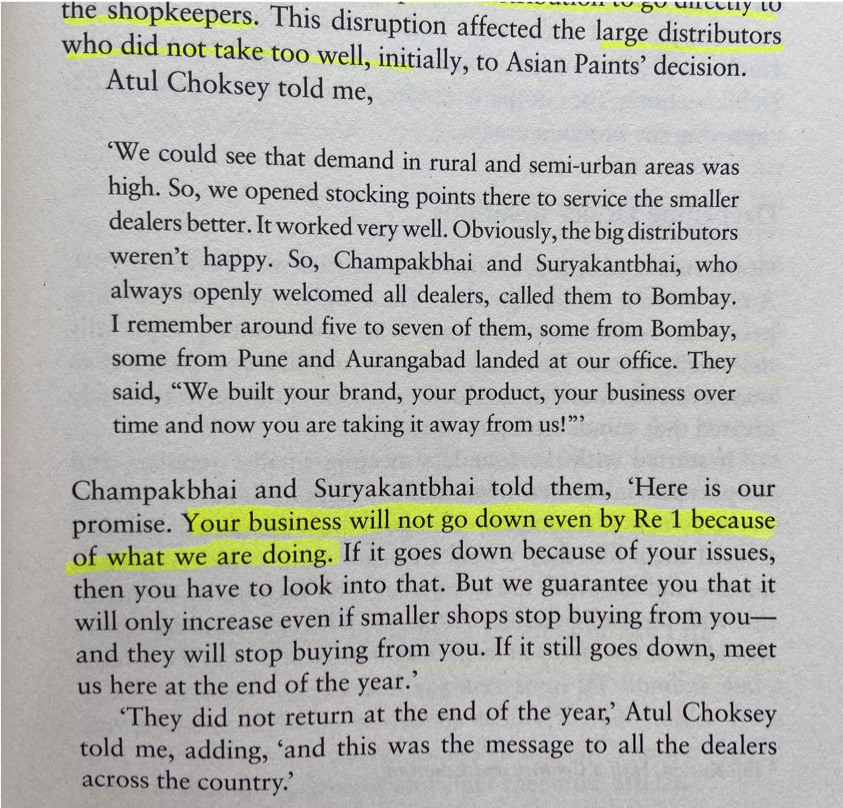

Asian Paints placed a huge emphasis on cultivating ‘kitchen relationships’, which was the term they used to describe the deep personal connections with dealers in their network. The company treated their dealers like family. One anecdote I heard was that it was very common for dealers to call upon their Asian Paints partners to help them pick spouses for their children! Champakbhai believed that for the company to be successful, their retail partners had to also be successful. And there was no shortage of these partners either.

Today Asian Paints has some 1.5 lakh retail touchpoints in the country. This is entirely unconventional when compared to the tradition of the industry. Whereas the foreign paint companies in India the 1900s relied on a few large distributors to get their products out, Asian Paints bucked the convention. They embarked on a carpet bombing of the market. They called this strategy an ‘open door’ or ‘open market’ policy, where they basically sold to anyone and everyone (who could pay within their desired credit period). They didn’t distinguish between the paint shop guy at the end of the road and the paint shop guy in the central business district or the paint shop guy in the village. They would all be treated the same.

This was how they bypassed the few large distributors who were effectively gatekeepers of the nascent foreign-dominated paints industry. They went straight to their consumers. They wanted to make sure that even poor villagers could get the right quality of paint at the right price. That’s how they became the ultimate mass market retail product. Even today paints is one of the only FMCG products in India that goes straight from the factory to the dealers.

At the time they started operations, paints was mostly known as an industrial sector product - not a consumer-facing sector. People either had a choice between expensive foreign paints brands, or unorganised low-quality local paints if they wanted to paint their houses - which wasn’t much of a choice at all. Asian Paints specifically targeted the decorative segment, and positioned themselves to solve the specific needs of Indian consumers. They gave them choice, variety, and for the first time tailored products specifically to regional requirements.

They began selling paints and distempers in smaller tins that were affordable to the masses. They used relatable brand names like Tractor Distemper and Three Mangoes gloss (which led to them being referred to as the ‘Mango company’). They also tailored products for regional use cases like the painting of bull horns in villages during Pongal (Tamil Nadu) and Pola (Maharashtra), or painting the front doors of homes in Tamil Nadu (which was done for auspicious reasons).

2. From the technology side -

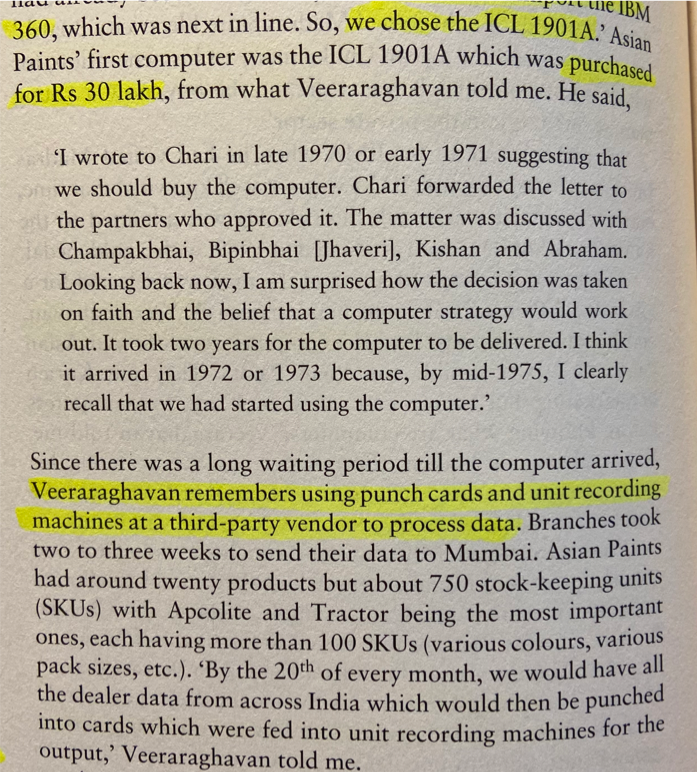

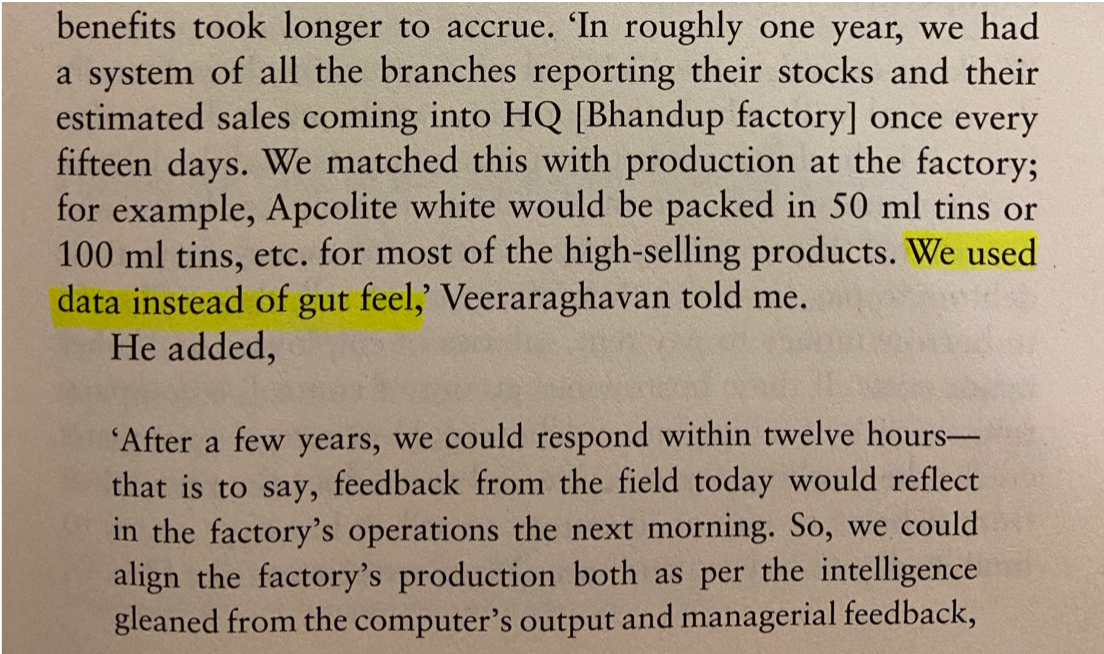

Tech has always been in their DNA. Their investments in ‘IT’ go as far back as the 70s, when they were among the first entities in India to purchase a mainframe computer [In India, Esso and the Tatas had also purchased a mainframe computer around the same era and historical records suggest at least two IITs and one IIM also had access to similar facilities]. It was so big that they had to store it in a separate building at their Bhandup plant. An IIM graduate named V. Veeraraghavan had been hired to figure out how Asian Paints could use computers (before most people at the company even knew what computers were).

At the time it was a huge bet. They effectively spent 1/10th of their total assets on the computer. When you consider the fact that this wasn’t even an IT company, it’s just insane to think about the risk of that decision. But it paid off. The computer allowed them to replace gut feel with data.

Those kind of benefits only compounded over the decades. It gave them the ability to plan and forecast, far before any of their competitors had those capabilities. The fact that they were able to anticipate demand at the dealer end, and replenish it even before the dealer had realised his stock is low…they could analyse patterns in demand, festive seasons etc knowing that this area in this state in this region will need this colour and quantity of paint at this time, so they could supply this beforehand. [Today Asian Paints trucks replenish the stocks throughout their vast dealer network four time every day, making for 1.6 lakh total deliveries every day]

It also meant they could be smarter with their inventory, and crucially manage their working capital better, which can often be make or break for these massive businesses. So while their competitors were operating in a sense of ‘commercial blindness’, waiting to hear back from wholesalers and retailers about which products were selling, Asian Paints could predict how many cans of orange paint they would sell at 8 pm in Matunga next Tuesday. The computer had all these other downstream effects like allowing them to introduce a programme of discounts for their dealers who paid within 30 days (over the course of the year). And of course when you look back, now they have this gigantic data advantage that allows them precision in their operations.

Of course, they also pioneered tinting machines in India. It was an idea first discovered by them in Fiji, where they leveraged the local Gujarati population to expand their operations abroad for the first time.

Tinting machines solved a lot of problems for dealers. Essentially a dealer can use these machines to create different paint shades on the spot - up to 1,000 shades with one machine. They don’t need to store all this different inventory. Initially dealers thought these were expensive, but now tinting machines are the norm for all paints companies here. This was Bharat Puri’s contribution in 1997.

Of course, now they have the balance sheet to outspend their competitors, on R&D, advertising, expansion etc. But it was their focus on people, and their focus on technology, that allowed them to separate themselves from the pack.

Asian Paints got to the top of their industry in 1967 - as the largest paints company in India - 25 years after they started. As you’ve mentioned, it’s a position they’ve never relinquished. This is a two-parter. First, I’m curious, what was in the DNA of the company that allowed them to fend off competition over so many decades and eras?

You know everyone has this perception about the old era of business in India, which was dominated by the License Raj. People say that markets weren’t open, there were so many restrictions, you were handcuffed from doing this and that. The assumption was always that to succeed in the License Raj, you didn’t need to know how to manage a business, you needed to know how to manage politicians. That’s how you made it.

But these guys didn’t know any politicians. The paints industry was dominated by foreign players when they started. In the 90s [when the economy opened up after Liberalisation] a lot of Indian businesses were suddenly faced with the shock of foreign competition. These guys had to handle it in the 1930s and 1940s. They had only foreign competition! It is difficult to appreciate the fact that Asian Paints was in as competitive a scenario in 1942 as they are in 2024. In fact, when they first started there were no licenses required, there were no permissions required, no barriers to entry. It was a free-for-all. They had all the competition in the world and yet they thrived.

So this is a company that has been forged in the ultimate competitive arena. They were built to compete.

Second - they’ve been on top from 1967 till now. That’s 57 years after they first reached the number one spot, and several decades after the last of the original founders passed away. That seems like it shouldn’t really be possible. What’s been the key to this endurance - what were some of the decisions that went into getting them to the top, and keeping them there all these years?

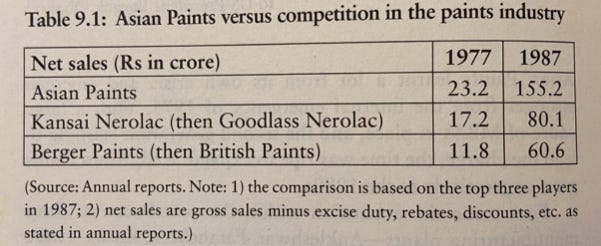

I’ve put a table somewhere in the book about how the rate at which they increased the distance between themselves and the next biggest players, that gap just kept on becoming wider.

That’s the cumulative effect of investments made, decades before the fruits of those investments have a chance to ripen. For Asian Paints it’s the result of investing in chemists and engineers in the 1950s. Those engineers opened the door to making high quality paints cheaply. The company could count on people like Jairam Nadkarni, who was the best polymer scientist at that time, hired after he graduated from the University Department of Chemical Technology (part of Bombay University at the time). He was instrumental in the design and structure of the Bhandup factory, and pioneered several methods of paint production.

Another one was increasing the management bandwidth of company leadership. A lot family businesses in India make it a point of only hiring among family and friends, or amongst their extended community. Marwaris are the greatest example of this. The benefit of this approach is there’s trust between counterparties. But the downside is your growth is capped at the expertise of your community. If you want to scale your business, you need to widen your search for talent.

Asian Paints took a big risk by choosing to hire directly from IIMs (that had only been set up in 1961). They were one of only three Indian companies to compete with MNCs for campus placements (and were the fifth largest recruiter of Indian MBAs in the first decade after the IIMs were inaugurated). That too, it was the only family business, and the only paints company in that list, and also “a company no one had heard of at that time.”

Guys like D. Madhukar and K. Rajagopalachari - two people they hired even before the MBAs came in - they freed up a lot of bandwidth for the founders. Remember that out of the four founders, one of them - Arvind Vakil - passed away very early. So there’s just three. Out of the three, as per the interviews I’ve had with their employees - Champaklal Choksey was the charismatic one. He was the visionary. He was outgoing, so therefore he became a steward of the Indian paints associations at the time. He saw the scale that others had achieved and raised his own ambitions.

See, all of these small decisions have gigantic outcomes when compounded over decades. If you take these risks early enough - like the decision to hire engineers, professional managers, buy a computer etc - and you get them right, they give you an advantage that is hard to make up. So even if your competitors copy you after your decisions have been proven correct - and all their competitors did - they will always be 5-10 years behind. The difference between Asian Paints and their competitors was that, while their competitors also noticed all the same trends, the leadership at Asian Paints anticipated them.

The chemists they hired in the 50s, the MBAs they hired in the 60s, the computer that came in in the 70s, these led to sales really going berserk only in the 80s. And the company is still reaping those benefits today.

What does the chessboard of Indian paints look like? What are the moats that Asian Paints has today as a result of investments over the decades?

I get this question a lot because all these new players have suddenly entered the paints sector in the last five years to shake up the industry after a really long time. But it’s difficult for me to answer because my story [with Asian Paints] ends in 1997.

My rudimentary take on this is that history tells us that competitive advantages don’t vanish very easily for companies that are very old. I take the example of something like Bajaj Auto. Bajaj Auto enjoyed a monopoly for a long time and yet they were beaten by competitors when the industry norm shifted from two-stroke to four-stroke engines - something that Hero Honda had figure out perfectly. Yet 15 years later they make a comeback with the Bajaj Pulsar - a 150 cc bike. Hero Honda couldn’t compete with them at all. And not only did they sell many Pulsars in India but they exported outside India as well. So it’s not like once your position is challenged you can’t or won’t make a comeback.

Look at Airtel - it’s a great example. Jio came in in 2016 and ruined everything for everyone in the telecom space. But here’s Airtel now - 8 years later they’ve made a comeback. History tells us that for the number 1 and number 2 player, things will generally be fine as long as they don’t doze off at the wheel. It’s the third, fourth, fifth and sixth industry players who need to be a little worried when new competent competitors enter their market.

The things that Asian Paints has done that has gotten them this nice Return On Capital Employed [ROCE] that everyone is drooling over (why else would these people be coming into paints?), they seem to think its easy enough. Astral, Pidilite, Jindal Steel, MRF, Grasim - so many of these guys are all thinking about paints now. Build a brand, build efficiencies right and you can get 25% ROCE. I don’t think it’s that easy. Competition will heat up, but I think it’s good for Asian Paints.

“We want to be part of the consumer decor lifecycle…We are not about just the four walls, we are now about in between the walls, and that’s the entire strategy of going from a share of surface to the share of space within the homes.”

- Amit Syngle (MD and CEO, Asian Paints)

If you look at their history of innovation, they’ve always been able to find an edge. They have their feelers far and wide now. Even something like tinting machines, they first discovered them in Fiji, being used by local dealers there. So even if competition comes in Asian Paints will probably find some gap that hasn’t been found yet - it could be AI, it could be IoT, it could be better service, could be something else. The Birlas [with Grasim] will definitely create short term disruption. I’ve heard that their entire team is from Asian Paints, besides their Head. For Asian Paints I would think that the kind of brand and goodwill they’ve built will take some time to be shaken. I would be more worried if I was Berger or Nerolac.

This is maybe a weird question that you might not be able to answer. Given that Asian Paints was so instrumental in coming up with new shades of paint, that they pioneered this new technology of colour mixing via their tinting machines, and coupled with the fact that their ads were so prevalent on colour TV, do you think it’s fair to say that they had a meaningful impact on the aesthetic sense of India, as a whole, at the time?

For the urban masses, I’d say yes, they definitely contributed to a wider choice. But that choice would have expanded in any case with the economic reforms of the 80s and 90s. Indian consumers were suddenly flooded with choice for almost every product they used. So I’d say Asian Paints didn’t play a singular role here, but they contributed to a changing zeitgeist.

The tinting machine was also only half the story. Putting the tinting machine in front of the consumer with a shade card - that took things to the next level. That cracked everything. And backing that up with an ad campaign. Then you have consumers expanding their preferences for what their homes should look like.

Even this can be contextualised as a symptom, rather than a cause. The cause was Champakbhai having the trust in someone like Bharat Puri to make these kinds of decisions - to choose an agency like Ogilvy, to back an expensive experiment like tinting machines, to retain that trust through mistakes made, to respect the expertise of his manager’s domain. Same with Veeraraghavan and the computer. Same with Nadkarni and the factory. The wherewithal for a family business to trust an ‘outsider’ with the reigns - that’s what made the difference.

On that note, you devoted an entire chapter to ‘Asian Paints - the consumer brand’. I spend a lot of time thinking about the consumer side of things in India. It’s been a topic we frequently go back to at Tigerfeathers because the products that are popular at any period of time are usually a reflection of Indian society at that time too.

You highlighted how Asian Paints was one of the first commodity products that became a beloved consumer brand in India. A lot of that was down to how the company leveraged this new medium of television, and specifically colour television when it was launched in India in 1982 [in time for the Asian Games, which were hosted by India]. So you essentially had a popular consumer product colliding with consumers that were ready to be marketed to - you called it the arrival of ‘The Great Indian Middle Class’.

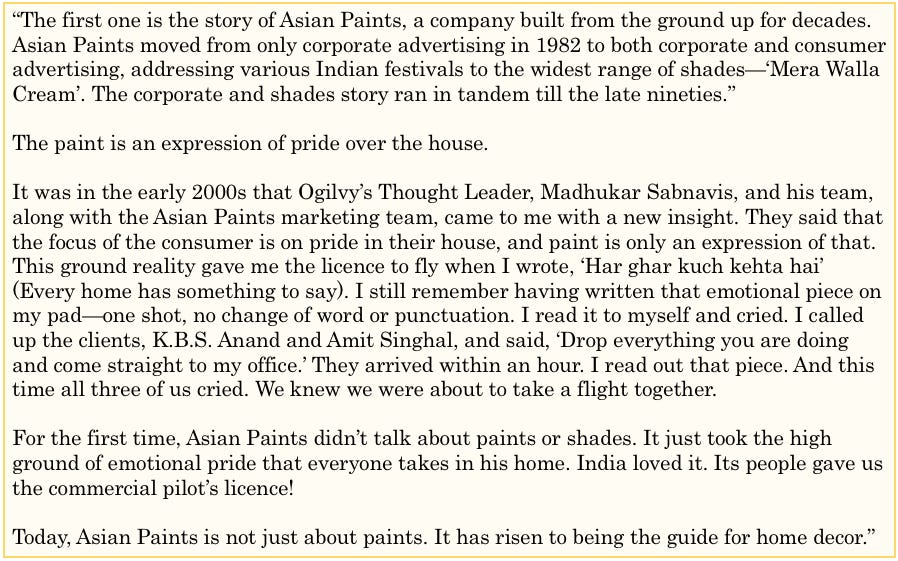

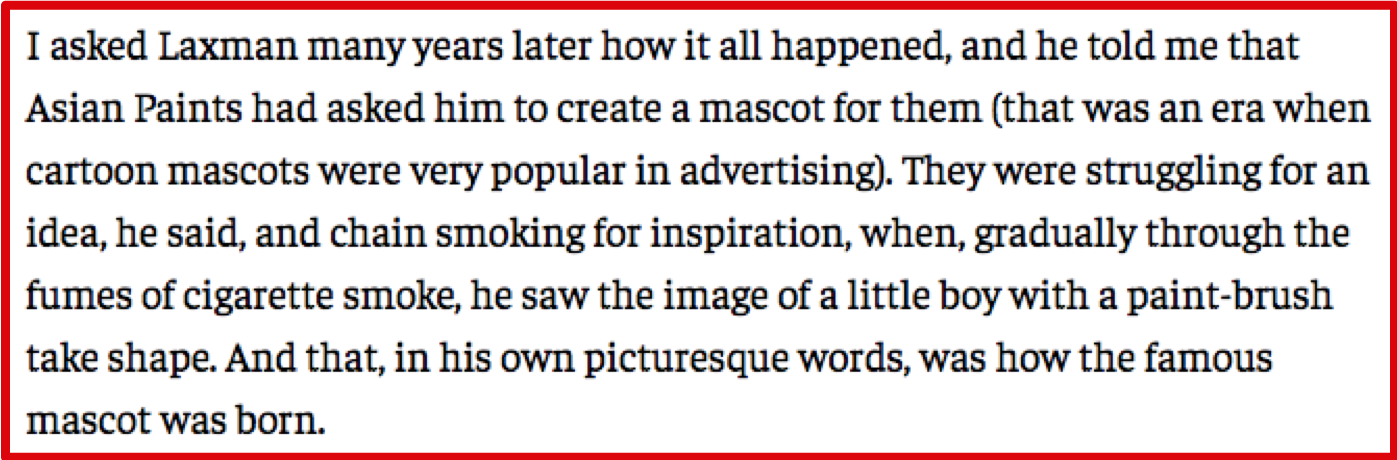

Marshall Mcluhan has this great quote that “The cave art of Madison Avenue has been by far the most innovative and educative art form of the twentieth century.” Given that Asian Paints roped in some of India’s finest creative minds - a legendary cartoonist like R.K. Laxman drew their mascot, A.R. Rahman contributed to one of their ad jingles, Ogilvy’s Piyush Pandey came up with their tagline - they clearly took a very deliberate, artistic approach to their communication. I’m curious what you learnt about Asian Paints’ approach to marketing and advertising that you could share with us.

The thing is - by the time the wave of consumerisation arrived, they already had a deep presence and brand recognition in the largest towns and cities in India. Their advantage was that they only had to adapt to a new medium, they didn’t have to start from scratch.

The collaboration between Bharat Puri [then the GM of Marketing at Asian Paints; now the MD of Pidilite Industries] and Piyush Pandey [Executive Chairman of Ogilvy India] changed the trajectory of Asian Paints in a way that even they couldn’t anticipate.

The way it happened was serendipitous - Bharat Puri has talked about it - the original ad line was ‘Celebrate with Asian Paints’ - something like that. The ad agency they had chosen came back with ‘Jashan banao Asian Paints mein’ - something that didn’t pack any emotional punch. Then they turned to Piyush Pandey, who came up with the campaign, the tagline, and the ads that changed everything.

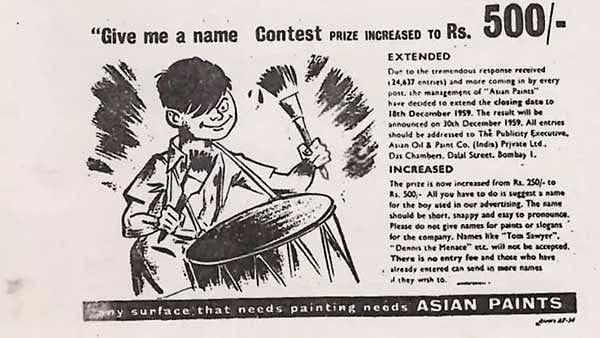

The original Onam ad, the Diwali ad…all are now iconic. Their mascot - Gattu - was created on request by R.K. Laxman, and used in various print ads, TV ads, and packaging till the 90s. It. was typically accompanied by the tagline ‘Any surface that needs painting needs Asian Paints’. It was a smash hit.

The name of the mascot came as a result of submissions received via a public competition. This image of a little mischievous boy with a paintbrush appealed to the masses, and people in the most remote parts of India started associating Asian Paints with the character.

The various savvy advertising moves converted them from a consumer product to one of India’s most beloved consumer brands. To be clear, the mix of advertising and paints wasn’t new. The foreign paints companies in India - Nerolac and Berger in particular - were already advertising on TV, even in an era of black and white television in the 70s. At the time Asian Paints mostly stuck to outdoor ads.

I was a kid in the 70s and my dad had a black and white TV at home. I remember one amazing ad in particular - I think it was Nerolac that did it. Picture this -

The scene was a party at someone’s house. The camera zooms from outside the house and goes in through this window. Everyone is talking and laughing, but in the background the theme from Jaws is playing, so you know something bad is about to happen. The disaster is that someone who’s eating his food gets his hand dirty and inadvertently places it on the wall. It’s something that could happen in anyone’s house. The host looks at it, at first appears alarmed, but then casually takes a napkin and just rubs it away. And that’s it. I still remember the camera work even now!

So these kinds of ads were there even before Asian Paints started advertising. But Asian Paints was the first to create an emotional connection with Indians. And they managed to bring it down to a local level, to the smallest town and village.

Because when you’re talking about local festivals - see, the black and white ads are still for an urban audience. These guys [Asian Paints] went right to the smaller towns, cities and villages with those ads and that character. What they got right in the areas was the demographic they were appealing to. This younger audience was on the way up. They latched onto those ad campaigns, and Asian Paints became their unanimous choice. Look at the Youtube comments on those ads today - they’re still teeming with nostalgia.

So those are the things that helped them make the transition from commodity to consumer product to consumer brand. Any commodity company - cements, paints, energy etc - if you want to take the next step to becoming a massive enterprise, you need to invest in building your brand with the final consumer, even though they may not be your primary buyer. That’s the lesson from Asian Paints.

Your book is not just the story of Asian Pains, but the story of Champaklal Choksey, who you’ve called ‘a doyen of the Indian paints industry’. I’ve heard you say in a few places that his name deserves to be spoken in the same breath as more frequently cited luminaries of Indian industry. Why is he such a unique figure - both as a founder and a person?

A lot of people in India don’t understand that when you reach the top of any company (I’m not talking about startups, I’m talking about real businesses), the ‘hard’ skills almost fade away.

For instance, when I was working on The Victory Project with Saurabh, we had the opportunity to interview some of the heavyweights of Indian business - some of the best business leaders in the country - people like Raamdeo Agarwal (from Motilal Oswal), Sanjeev Bikhchandani (from Info Edge), and several others. One thing I noticed during our meetings with them - their phone didn’t ring even once. We had their full attention.

I think the ability to genuinely connect with all your stakeholders is a skill that the best Indian business leaders exude. And every CEO I’ve met, and many have even explicitly confirmed this, their education, their accomplishments, their technical knowledge…these ‘hard things’ all fade away against their personal skills. Ultimately it’s the ability to build consensus amongst all their stakeholders (without upsetting anyone in a big way) that makes the biggest contribution to their success. The best business leaders are the ones that master this.

This is true of Champaklal Choksey. His ability to build relationships with his dealers, his employees, his partners, his children, their children - that personal touch was his hallmark, that ability to build consensus was his edge. And the foundation of that consensus wasn’t the individual, but the institution. The ability to recognise that the institution is bigger than the individual, that kind of wisdom typically comes very late in life, but he understood this right from the start.

That’s what allowed him to go to his Bhandup factory and placate a violent set of protesting workers during the union strikes. That’s what allowed him to connect with partners in Japan, the US, the Polynesian islands. That’s what allowed him to lead national paints associations. It’s what allowed him to connect with hotshot MBAs, and woo them away from MNCs like HUL and Citibank (something that is always difficult to do in family businesses because the top posts are always occupied by family members). It’s what enabled him to be the ‘first among equals’ with his founding partners.

The challenge of taking a family business and turning it into a professionally-run industry-leading institution - he was the first to take on, and to prove it could be done in a sustainable way. There were others that had attempted it and failed before him. And others like Rahul Bajaj who were equally successful after. But Asian Paints set the path.

What would you say is his biggest legacy - to the philosophy of Indian business and to India in general? What could today’s founders learn from his story?

The same thing I said at the start - honesty and scale.

As an entrepreneur, first you need to ask yourself why you’re doing this. If you’re starting with just passion, India tends to teach you a very painful lesson. If you’re starting with a desire to do hard work, create a revenue-generating business, and have a bit left over for yourself at the end of the day, and your goal is first and foremost to survive, then you might have something on your hands.

“Live with dignity, never be dependent on your children or anyone else, have a house and bank balance of your own till you are alive — these were some of the lessons we learnt from him”

Champakbhai had the humility to place the company before himself - always. We currently belong to an era where a person is supposed to put himself above others. There’s a certain value attached to being this transcendent, charismatic, messianic founder. You know the famous exchange between Softbank’s Masayoshi Son and WeWork’s Adam Neumann where the former told the entrepreneur “you’re not crazy enough”. That kind of discourse places a lot of emphasis on the founder, instead of the business. It’s emblematic of an era where as a startup founder you’re given tons of money just to put your competitor out of business. So you’re not starting from a place of building an institution, you’re starting from a position of winging it.

“…he had always taught us that the company was not our property. The house that we are living in might be our property. But the business belonged to all the shareholders.”

When I look at Champaklal Choksey and the values with which he started his paints business, he was sure (and this has come from all my interviews) that for Asian Paints to survive, the industry must do well. So he never disrupted the industry. He established the best practices for all paints players, and, as history has shown, made several big decisions about the future of the industry that were proven gloriously right. If you’re still at the top after 55 years of huge societal, technological, and economic change - you’ve probably done something right.

I met the chairman of Nerolac - a gentleman in his 90’s now - he said that whenever the industry had a problem, they would go to Champakbhai. Champakbhai would say “Ok we’ll increase our prices so everyone else can increase their prices, but only by this much.” His thinking was clear - ‘everyone should make money, but we should make the most’. Asian Paints even once manufactured paints for their competitors when there were production interruptions because of labour disputes! So it was his ability to get the industry together, his ability to take high-stakes decisions for the benefit of everyone that makes him stand out. I don’t know if we see that in today’s generation of Indian business leaders.

Remember I’m hearing all this from one of his main competitors! So everyone had accepted that Champakbhai and Asian Paints were number one. Without him no one else was going to win, no one else was going to survive. The industry wasn’t going to progress. His competitors all understood “If I have to survive and do well, he will probably make more money than me, but that’s okay. Everyone wins if Asian Paints wins.”

What is the process of writing a book like this? What does the task of researching look like? What’s the funnest part? Whats the hardest part?

There’s no fun, I can tell you that! Jokes aside, in this book there were three levels to research:

The first level was the family - I was very lucky to have met all four children of Champakbhai - three sons and one daughter, and few other well wishers. These were people in their 70s, 80s, 90s - it was a real honour to speak with them.

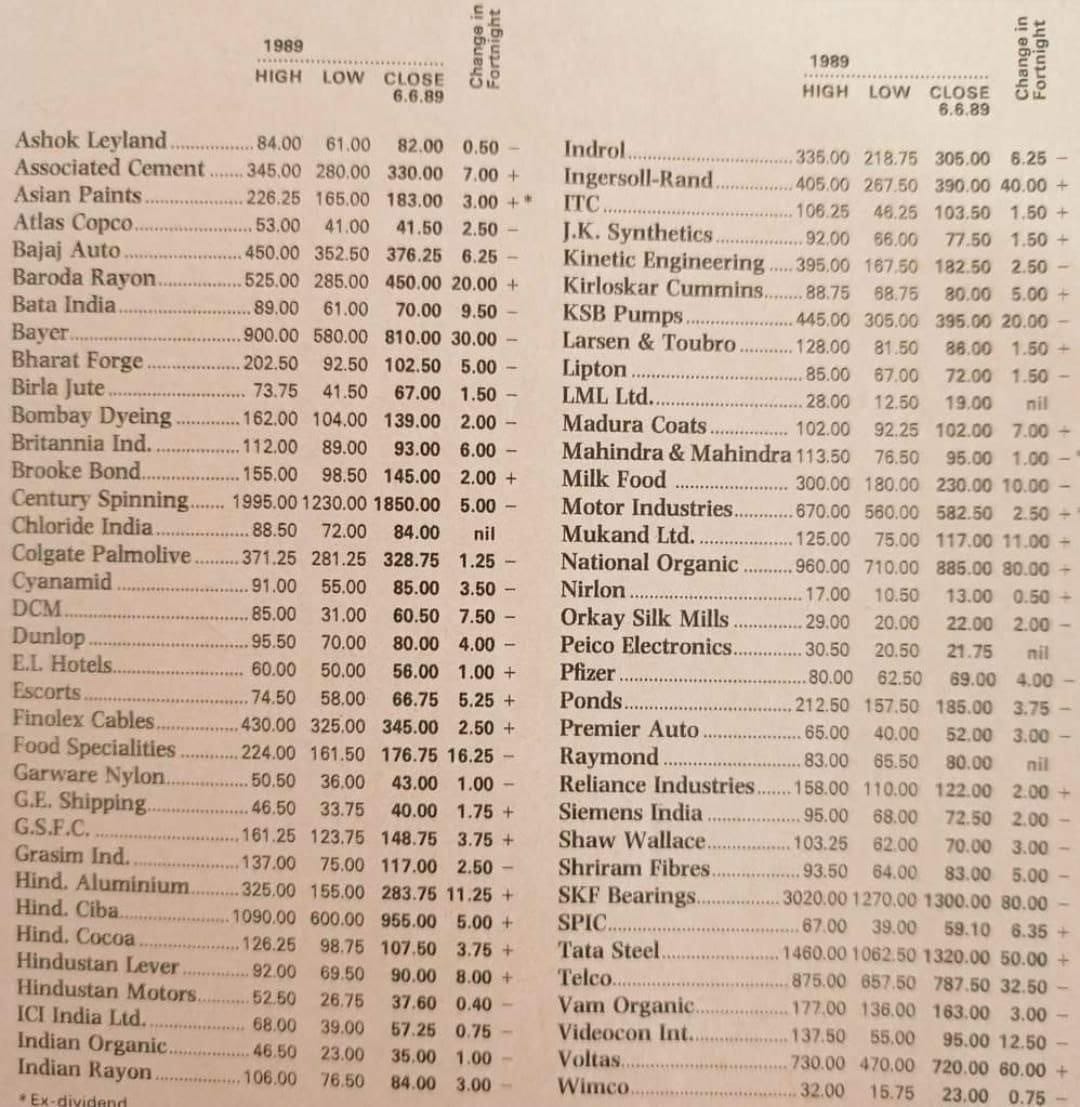

The second level was to get access to the Asian Paints annual reports from the 1980s. People probably don’t know this (or care about this) but annual reports from that era are simply not available. At all. I went to the Ministry of Corporate Affairs - no luck. I was very lucky that someone introduced me to Chinmay Tumbe [Faculty at IIM Ahmedabad] - who gave me access to the IIM-A archives. That’s where I got the Asian Paints annual reports from the 70s and 80s. It’s hilarious when you think about it, right? Today if you want an annual report on any company you’ll just go to their website and there it is. Or you’ll go to the BSE or NSE. But you’ll likely only get them till the early 2000s at most.

Here’s a fun fact - there are only two companies in India - both Nifty companies - who have their annual reports in PDF-form on their websites from the day they were listed. One of them is Infosys - which you would expect - as a paragon of corporate governance. Even TCS doesn’t have it’s reports before 2004. Infosys has them till 1983. You got to the Infosys website and you’ll find all their annual reports. It’s a pity more people don’t care. If people want to really learn about the history of industry in India they should read those reports. The second company is Reliance. RIL has its annual reports from 1977 on their website in PDF form. Its weird that there are no more from that era, but that’s how it is.The third level of research - that was the most fun - was travelling and meeting ex-employees of Asian Paints. I went to Bangalore, Chennai and Hyderabad mainly to meet these folks. I even contacted someone who joined Asian Paints in the 1960s - a gentleman who’s in his 80s now - living in New Zealand. Thankfully he’s come back to India now - Pramesh Khanna. I spoke to him on a Zoom call.

So the book was born out of these three levels of research - the factual component, which came from the annual reports. The anecdotal component, which came from the employees and other stakeholders. And the personal component, which came from the Choksey family.

Given this is your third book – your second solo project and third in total - I’d love to know what you’ve learnt about the process of writing books in general over the years?

I always loved writing. That’s one of the reasons why I left the sell side [analysis desk]. The sell side gave me a really nice opportunity to write, but it was restricted to ‘buy this’ and ‘sell that’. Buy this stock and sell that stock etc. Which is extremely lucrative, sure, but not as creatively fulfilling. I did it for a while and got bored. Long-form writing, or writing a book, gives you a much wider canvas to establish a narrative, where there’s more room for nuance.

Writing in general comes very easily to me. Social media has helped to give me a platform to get my writing out - I used to blog in the 2000s (via Blogger) and now obviously I share my thoughts on Twitter - which has unfortunately also destroyed everyone’s attention span. I’m glad there’s people like you that are still keeping long-form reading and writing alive…

It’s destroyed my attention span too, just to clarify.

…so writing was always there for me. The process of writing - especially chunky projects like this - I really enjoy. For any project first you start with a big picture, then you bring it down to a framework, then you break it down into chapters. Then you give yourself a target - like 1,000 words per day. Get to 30,000 words at the end of the month. In a couple of months you have a manuscript. That’s how it goes. The research part of it took much longer, but the actual writing took just three months.

Switching lanes here. You’ve been equally prolific across different wickets too. Outside of writing - Paisa Vaisa is one of the longest running podcasts in India - congrats on your 7th anniversary, by the way. You’ve also done a podcast mini-series called The Last Brand Standing, and you’ve got a new Youtube show called Reputation Matters that just launched.

I’m curious what your journey as an Internet creator has been like. What has changed about the podcasting landscape since you started? At the very least it feels like podcasting has become far more mainstream in India in recent years.

I’ve been very lucky that I have folks like Amit Doshi [Founder and Head at IVM Podcasts] helping me with the heavy lifting. He’s the person who should actually be here answering your questions. If I had to do everything on my own I probably wouldn’t have made it. He reached out to me in 2017 saying “come over to IVM and do this with us”.

I was always deeply interested in podcasts. In 2007, 2008, 2009 - at the time of the global financial crisis - I started listening to Planet Money. At the time I was like 'wow why aren’t more people doing this?’ Why is this not being done all over the world? And to see the money that NPR was spending on the show - the website, the production etc - it was incredible.

Cut to five-six years later I was working out in the gym and I got a recommendation for Serial [the hit investigative journalism podcast, now owned by The New York Times]. I couldn’t stop listening. Here I am on the treadmill and Sarah Koenig’s voice suddenly came on. I was hooked. That’s when podcasts were becoming mainstream in the West. A year later Amit reached out to me.

The first idea he pitched was quite different than what the show eventually became. The original idea was that I would speak for two minutes on concepts around money - what is a mutual fund, what is a bond etc. And we would do it thrice a week. So six minutes of recording per week. I got bored of that very fast. Six months in I called Amit and said “Hey this isn’t working for me.” So he asked me what I wanted to do. I said I wanted more of a dialogue, more of a two-way conversational format. Our very first guest was Mahavir Chopra - who was working at Coverfox, an insurance aggregator.

And so 2017, 2018 was like my golden era. I had Aashish Somaiyaa (then with Motilal Oswal), I had Kalpen Parekh (still with DSP), and I had Nitin Kamath (from Zerodha) - all come on the show over a very short time span. That’s when I knew I had something. The episodes, of course, went nowhere. And the brands didn’t understand the power of the medium either.

When I got Morgan Housel on in 2019, I managed to leverage that into a sponsorship deal for the podcast. The great Pravin Jadhav - now the founder at Dhan, then working at PayTM Money, agreed to sponsor our show for six months on the back of that episode. But the podcast ‘ecosystem’ didn’t really exist till the pandemic. Thats when things took off for me (and I suspect for a lot of people). We’ve just launched our Youtube channel now - probably a little late - because podcasts now have to be full-fledged video productions.

So my success owes a lot to Amit Doshi from IVM, and the fact that I was focusing on one thing. And my commitment was that every single Monday there would be a new episode of Paisa Vaisa published. That’s it.

It was an editorial decision from Day 1 that I will never be the guy telling you how to ‘double your money in 5 days’. The ecosystem has become like that - no problem. But I’m never going to do any of the ‘make 12% returns every year -guaranteed’ stuff. And I’m not gonna be the guy to tell you how to analyse a balance sheet either. I’m very happy to see that space grow, and the fact that there are other ‘finfluencers’ that do that well. But that’s not my space. I would rather spend time talking to people, having genuine conversations, so that listeners can learn more about money, and educate themselves so they’re better placed to make smarter decisions about their personal finances.

Because you’ve been under the IVM umbrella for so long, because you’ve been doing Paisa Vaisa for so long, you’ve had this front row seat to the evolution of podcasting in India. IVM itself was recently acquired by another startup - Pratilipi. What’s your take on how the business of podcasting has changed in India? Have brands realised the importance of getting in front of a podcast audience?

Brands are so aware that they all want to have their own podcasts now!

Somewhere I think brands have recognised that podcasts are here to stay. Podcasts are valuable properties - it’s just an open question around what’s the best way to monetise them. I don’t think brands are at a point where they know how to ‘own’ high quality content, or how to properly leverage that kind of IP. Look at Wondery in the US - they make premium audio shows and seem to have figured out the IP game, and the balance between advertising and subscription.

In India, if you’re trying to run a podcast as a business today, I think it’s tough if you don’t have sponsors. At Paisa Vaisa we ran an experiment last year around subscriptions. We launched a subscription product on 1 January 2023, but shuttered it only a few months later. It just didn’t work. We were charging ₹699 for early access, bonus material, access to the archives etc, but we found that enough subscribers just aren’t willing to pay for that type of content yet. It was disappointing, but useful to know. In any case you need to keep trying things to figure out what works. Video seems to be where this game is headed. I’m fortunate to have partners like IVM who continue to put in the hard work to create an economic ecosystem around podcasting in India today.

To wrap up, I have five random questions unrelated to anything we’ve just discussed. They range from the trivial to the potentially profound. Hope that’s okay.

First up, what is something you strongly believe about India that not enough people talk about?

That’s a tough one. I’ll give you a negative first, then a positive.

First, something I strongly believe is that India has always had a chronic underinvestment in education. It doesn’t get any attention, doesn’t get any mileage, but I think it’s something that should be discussed way more. If you look at the history of all the leading countries in the world - in the US, Europe, China - somewhere along the way their leaders took a strong call on education. Until you crack education - whatever approach that takes - it’s difficult to make real progress. A lot of India’s problems today are downstream from a lack of quality education for the majority of our citizens. I don’t understand why a reasonably good quality of education can’t be made available to every child in the country, regardless of their financial background. Delhi is trying this to some extent. But at scale in India, we’ve faced miserably on this count.

The second thing that people don’t talk about enough is India’s resilience. I think India is phenomenally resilient in a multitude of ways. I don’t know if politics is the reason for that or demographics or something else, but I think that the way we respond to crises now has become much smarter, much faster than ever before. We currently have a competitive edge (as a result of our demographic dividend) that will probably expire in another 15 years if we don’t make the most of it. We have this short window to take advantage of until we’re staring at a massive population of retirees that will be more of a strain than an asset. It’s incumbent on this generation to lay the foundation for what comes after.

What is your favourite time of day?

Probably 4-6 pm, post lunchtime. I love that time. It offers you the luxury of both flexibility and creativity when it comes to filling in that slot. That’s when I get a chance to hang out with my friends (since I don’t have a typical 9-5 gig), take my wife for a coffee, and finish off my writing goals for the day. I’ll often escape to a coffee shop to get my 1000 words done if things are too chaotic at home.

What is a person or topic or company in India that you want to read a book about, but no one’s written it yet?

That’s an easy one - Reliance. When you consider it, India has only seen three really massive business families - the Tatas, the Birlas, and the Ambanis, and only the latter is still in its second generation. It’s insane what that company has done.

The stuff that happens under the hood there…who wouldn’t want to read about that? Yes, it would have to be the story of RIL and Mukesh Ambani. Here’s a guy who - in his 20s - had to leave his education and rush back home to contribute to the family business because of his father’s health issues. He and his brother had to work their asses off to build this thing. Building refineries in India in the 80s was no simple task. The choices and decisions that went into the ascent of RIL in the business environment of 70s and 80s in India - I’d love to learn about that. And that’s before you even get to the ‘data is the new oil’ phase with Jio.

I think we often think of these people and these families just in terms of market caps, Forbes lists, and valuations. We don’t appreciate the weight of expectation on their shoulders, or how much can go wrong. That level of execution is underrated, and worth studying closely.

You mentioned the 4-6 pm thing. Like you said, you don’t have a typical 9-5 job. You had a pretty traditional finance career for 20 years, and for the last 7 you’ve had an Internet career, splitting your time as an author and podcaster. So that being said…I stole this question from a podcast I heard recently. There’s this famous American military strategist and fighter pilot named John Boyd, who had a great quote - “To be somebody or to do something. In life there is often a roll call. That’s when you will have to make a decision. To be or to do? Which way will you go?”

I found that question to be quite instructive when framing my own career, which also started conventionally but is now very much a weird Internet-based amalgamation. I’m curious, when you think about your own professional trajectory - where you’ve been, where you are, and where you want to go - would you rather ‘be’ or ‘do’?

I would rather be. I just want to be in the moment. The ‘do’ depends on my being. It’s not the other way around. My frame of mind is how I am today - my health, how I think - that’s what’s going to define what I do. If I’m not in the best of places physically, mentally, emotionally - that’s going to show in my output. Champakbhai is a great example. He was such a fit and agile guy - physically and mentally. All of it comes from having a ferociously curious mind. So only when his state of being was at that level could he execute what he needed to.

And finally, this is a question that my partner and I have wrestled with for ages. If you had the ability to either fly or teleport, which one would you choose?

Easy - I’d teleport back in time - and tweak a few random dials here and there.

Thank you Anupam, that was brilliant, appreciate you taking the time.

You can grab a copy of Anupam’s book on Amazon, Flipkart, and everywhere else you usually buy books.

Sources & Additional Reading

The Unusual Billionaires by Saurabh Mukherjea

Oxford History of Indian Business by Tripathi Dwijendra

A Business History of India by Tirthankar Roy

Branded in History by RAMYA RAMAMURTHY

Against All Odds: The IT Story of India by S. Kris Gopalakrishnan, N. Dayasindhu and Krishnan Narayanan

India Unbound: from Independence to the Global Information age by Gurcharan Das

The Elephant Paradigm by Gurcharan Das

Half A Century And Still At The Crease by Biji Kurien

Pandeymonium by Piyush Pandey

The Boom and Bust of Bombay Mills

The story behind RK Laxman's 'Gattu ke papa' and Asian Paints

If you made it all the way here and you thought this was a good use of your time, it would mean a lot to us if you took a couple of seconds to share this post.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rahul Sanghi is the co-founder of Tigerfeathers, where he’s building a time capsule for 21st century India. He most recently served as Fintech Lead for Visa in India & South Asia. He began his career as a consultant with KPMG in London, spending a majority of his time helping the firm set up its global enterprise blockchain and crypto asset advisory practice. He moved back to India in 2018 and joined Koinex (then India’s largest cryptocurrency exchange) as Director of Business and Strategy, before assuming the same role at B2B-SaaS startup FloBiz. Along with writing at Tigerfeathers, he currently spends half his time as an Amorphous Blob at O’Shaughnessy Ventures. He doesn’t know why he’s writing this in third person, but whatever.