Hey everyone👋

Welcome to the 986 new subscribers who’ve joined since the last time we did a roll call. To everyone else, thank you for sticking with us through what is officially Year 1 of Tigerfeathers!

At some point we’re going to turn a mirror onto this amazing community (i.e. you guys) that has supported us through the last 12 months. We’re still figuring out the best way to do this so if you have any suggestions, we’re all ears. For now, all you need to know is that you’re in great company.

Today’s essay is about a concept you’re going to be hearing about much more in the years to come - the Metaverse. It is a term borrowed from the pages of sci-fi that refers to the next era of the Internet - one that will be defined by virtual currencies, virtual reality and virtual goods (i.e. Non-Fungible Tokens or NFTs).

As always, this isn’t a short piece. But if you do make it all the way to the end, you will get:

- a conceptual understanding of the Metaverse - what is it, why is it important, why should you care?

- a brief history of the Internet and how we got here - what worked, what didn’t, and why we’re transitioning to Web 3.0

- an introduction to Decentralisation and why it matters

- a deep-ish dive on why Bitcoin and other crypto assets are so crucial to the future of the Internet

- a view on the current state of the Metaverse and how you can get involved

I’d love to know what you think. Feel free to get in touch on Twitter or just reply to this email.

And with that, I’ll leave you to it.

"It won't pay the rent, but that's okay — when you live in a shithole, there's always the Metaverse, and in the Metaverse, Hiro Protagonist is a warrior prince."

- Neal Stephenson (Snow Crash)

Reality is being given a run for its money.

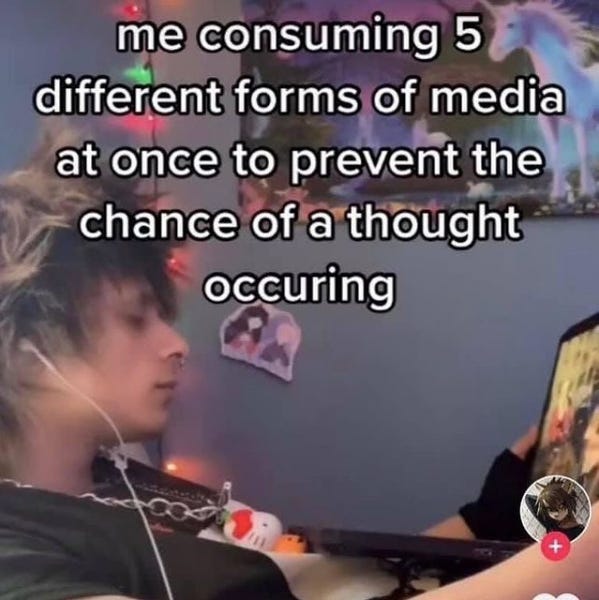

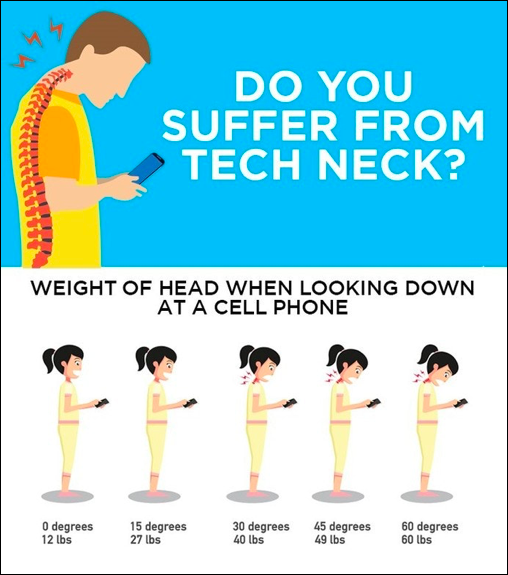

The physical world has become a bit…outdated. If nothing else, it is surely past its prime. Why else would we spend so much of our days glued to our devices?

Most smartphones today will give you a friendly reminder of how much time you’ve spent staring at your screen (just the mobile version) over the past seven days. In a good week, I’ll keep it tight - somewhere around 4 hours a day. But over the course of the last 18 months I’ve broken my previous high scores at an Olympic level. I suspect I’m not alone here.

No one wants to know how many minutes they’ve frittered away glued to their phones scrolling through the multicoloured vistas of Twitter, Snapchat or Instagram. Do you really need to see how much of your attention is being sucked away through the fangs of Netflix and Youtube? You can’t help but tap away on your email, your games, your workout tracker, and your stock portfolio. Its not our fault that so much of our personal and professional lives are now tangled up in the mosaic that makes up our home screens. And yet our phones have the audacity to present us with recurring warnings about our escalating digital dependency (as if we didn’t already know).

The default (and understandable) reactions to statistics like this often come in the following variety:

“Kids these days don’t appreciate the joys of playing outside”

“Internet addiction is killing our attention spans”

“We are losing our ability to live in the moment”

“All this screen time can’t be good for your mental health”

“I might ditch my smartphone for an old Nokia 3220”

“Thats like really scary, but omg wanna try this new TikTok challenge?”

These are all reasonable responses to phenomena that everyone has likely observed or experienced themselves. But that’s only part of the story.

Becoming Limitless

That the smartphone has been a species-altering addition to human life is not up for debate. Our portable black mirrors have changed the way we live, work and play. For all the amazing ways our Internet-enabled devices have enriched our lives, there was always going to be a pound of flesh to offer in return.

You know the movie Limitless? The plot centres around an experimental drug called NZT-48 that supercharges the cognitive abilities of the main character (Bradley Cooper), allowing him to access 100% of his brain’s potential. Initially he enjoys flexing the full range of his expanded mental acuity. However his fantasy life eventually unravels as he has to reckon with the deadly biological and sociological side effects that are to be expected of such a brazen attempt at hacking into the natural order of things.

How is this relevant? Well, the smartphone was like NZT-48 for the entire human race. It gave us access to the entirety of human knowledge in the palm of our hands. At the same time it also dramatically expanded the surface area of human interaction. This scale of change was never going to come without consequences.

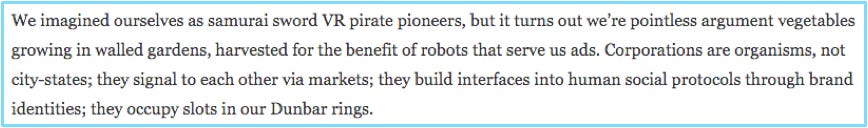

We play a delicate high-stakes game when it come to advancing our technological prowess. The more we move from science-fiction to science-fact, the more violently we lurch ourselves into an unpredictable and unknowable future. In The Gig Economy, sci-fi writer zerohplovecraft articulated the penchant for dystopia that distinguishes the current stage of our techno-economic cycle, writing that:

It doesn’t take much imagination to lampoon our fixation with our screens and smartphones. The nation of online is a curious beast - a mixed breed of information and entertainment. On any given day you could find yourself contorting your body to the latest TikTok challenge or ape-ing into the newest crypto trends. On another you could find yourself in the groundswell of a revolution to bring down a hedge fund or a government. On most days you could just find yourself swept away in the tide of odd things people do to find love and make money online (or vice versa).

Marshall Mcluhan once said that “We shape our tools, and thereafter our tools shape us.” Today so much of us is in our devices. And that’s because for the last decade (give or take) we have remodelled our social, cultural and economic lives around the mobile internet. It has led to an age of strange paradoxes.

Smartphones have allowed us to simultaneously:

be social and anti-social

know important facts about unimportant matters

save time and fill it with distractions

feel more and less connected

Most of all, the mobile internet allowed us to be here and not here at the same time, because it fractured our reality into online and offline. The arrival of the smartphone was one of those anthropological lines in the sand that divided the world into a ‘before’ and ‘after’. Just like the invention of electricity, airplanes or cars, we were always going to need some time to adapt.

Earthbrains & Bicycles

‘Becoming cyborgs’ was always going to be a milestone in our evolutionary roadmap (sort of). Humans have mastered the art of inventing and utilising tools to tame our natural environment. It is one of the main tricks that separates us from other species, helping us to overcome our biological limitations and establish mastery over our surroundings.

Steve Jobs once famously declared that “the computer is the most remarkable tool that we’ve ever come up with. It’s the equivalent of a bicycle for our minds.” What’s insane is that he made that remark in 1980, when we had barely scratched the surface of the computing revolution.

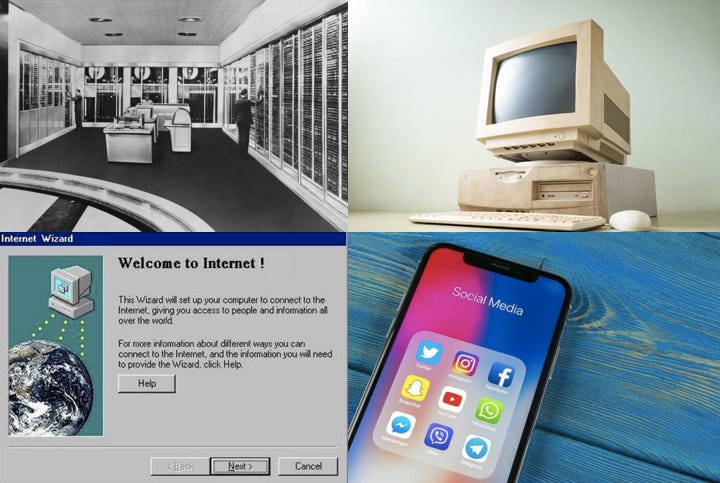

From the midway point of the 19th century, we’ve cycled through roughly four major eras of computing. This began in the 50s and 60s with the invention of mainframe computers (i.e. big ass computers). Things started to take off in the 70s and 80s with the popularisation of personal computers, bolstered by the addition of industry heavyweights like Microsoft and Apple to the fray. The 90s and 00s saw the mainstream arrival of the commercial Internet, and with it the bedlam and riches and disasters of the Dot Com bubble. We’re now at the tail end of the fourth era of computing which has been defined by the smartphone, and the unshackling of the web from homes and offices. Along with ushering an exponential level of progress, each era has brought with it new social, economic and psychological baggage that we’ve had to learn to carry.

The same is true for the Internet itself. Every step forward in computing excavated a fresh entry point for the Internet to burrow its way into our lives. Amidst the omnipresence of tech giants in our public consciousness today, it is easy to forget that the Internet (as we know it) has only been around for 30-odd years.

Catalysed by the paranoia of the Cold War, the Internet (or ARPAnet) was originally developed by the US Department of Defence as a way to share information between its own computers (and particularly as a way to preserve communication networks in the event of a nuclear attack). One of the first beneficiaries of this connectivity were American and British universities, which were now able to share academic research and scientific discoveries with each other from across the pond.

It wasn’t till the adoption of common standards and protocols for transmitting data that the concept of an ‘Intergalactic Computer Network’ could truly be realised. This alliance of hardware and software would lay the foundations for an “electronic commons open to all - the main and essential medium of informational interaction for governments, institutions, corporations, and individuals.” It would produce a global shockwave akin to the second coming of the printing press. This early vision for the Internet (colloquially referred to as Web 1.0) was one of boundless optimism.

When wireless is perfectly applied the whole earth will be converted into a huge brain, which in fact it is, all things being particles of a real and rhythmic whole.

- Nikola Tesla in 1926

The hope was that the Internet would democratise access to information and knowledge for all, allowing for the full autonomy of the individual. Despite initially delivering on its promise, the last decade hasn’t exactly gone to plan.

So how did we go from this:

To this?

Owning the sidewalks

“Humans were always far better at inventing tools than using them wisely.”

― Yuval Noah Harari (Sapiens)

The techno-utopian dream was of an Internet that resembled an invisible city where people, corporations and governments could set their stalls on ground that was owned by no one. The laws of the land would uphold the sovereignty of the individual, allowing people from anywhere in the world to use this public infrastructure to enrich their lives.

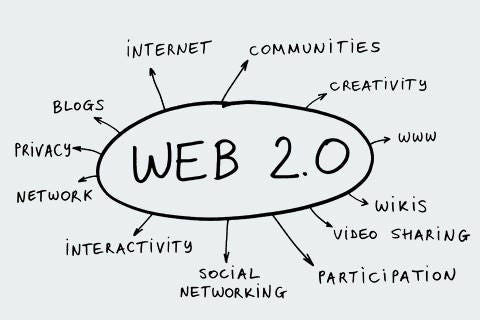

The second epoch of the Internet (Web 2.0) put this vision at risk.

The mad rush to commercialise the web in the late 90s led to one of the frothiest bubbles of all time. A gold rush of historic proportions. And entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley grabbed every shovel they could get their hands on. There were some unmitigated disasters that came out of this era (like WebVan.com), some ideas that were ahead of their time (like Pets.com), some that fizzled out (like GeoCities), and some companies like Amazon and eBay that withstood the crash of the Dot Com Bubble to become formidable towers in the global economic skyline.

The backlash from the bubble hadn’t hurt the zeal that had set in for launching online ventures (In spring 1999, one in twelve Americans admitted that they were in some stage of founding a business). Although entrepreneurs had been given a reality check on the impotence of early Internet business models, there was still hope that the right contender in the right time and place would be able to crack the code.

Enter: Web 2.0

From the mid-2000s onwards, the Internet became *Social*. The next generation of tech startups had similar playbooks that have since been appropriately summarised within the axiom ‘come for the tool, stay for the network’. This class of companies included the likes of Facebook, Twitter, Digg, Blogger, LinkedIn and dozens of others who each sought to prepare the most alluring stage for people to meet online. Although the context differed from platform to platform, the broad range of functionalities remained the same:

- allow users to create public profiles based on their real world identities

- provide them with simple tools to upload and share media (status updates, comments, blogposts, pictures, videos)

- arrange this user-generated content within an algorithmically determined feed that was tailored to suit individual preferences

- provide the best port of entry for people to import their real world social graphs into a digital setting

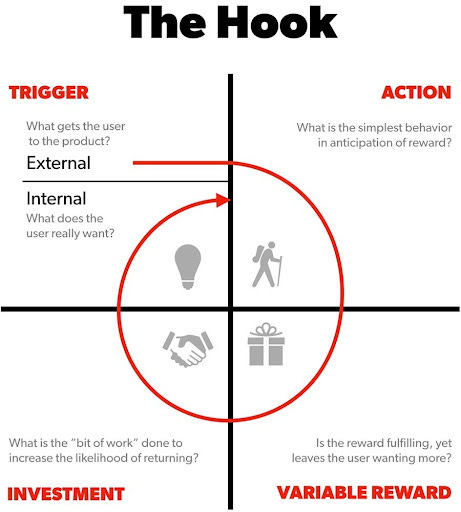

This combustible mix of features was then ignited by elements of gamification like follower counts, subscribers, likes, and reposts which matured into a full blown inferno once these websites found a natural home in our mobile app stores. The arrival of social media, cloud computing and smartphones meant that the Internet had now become a personal, perennial travel companion - one that always aimed to please.

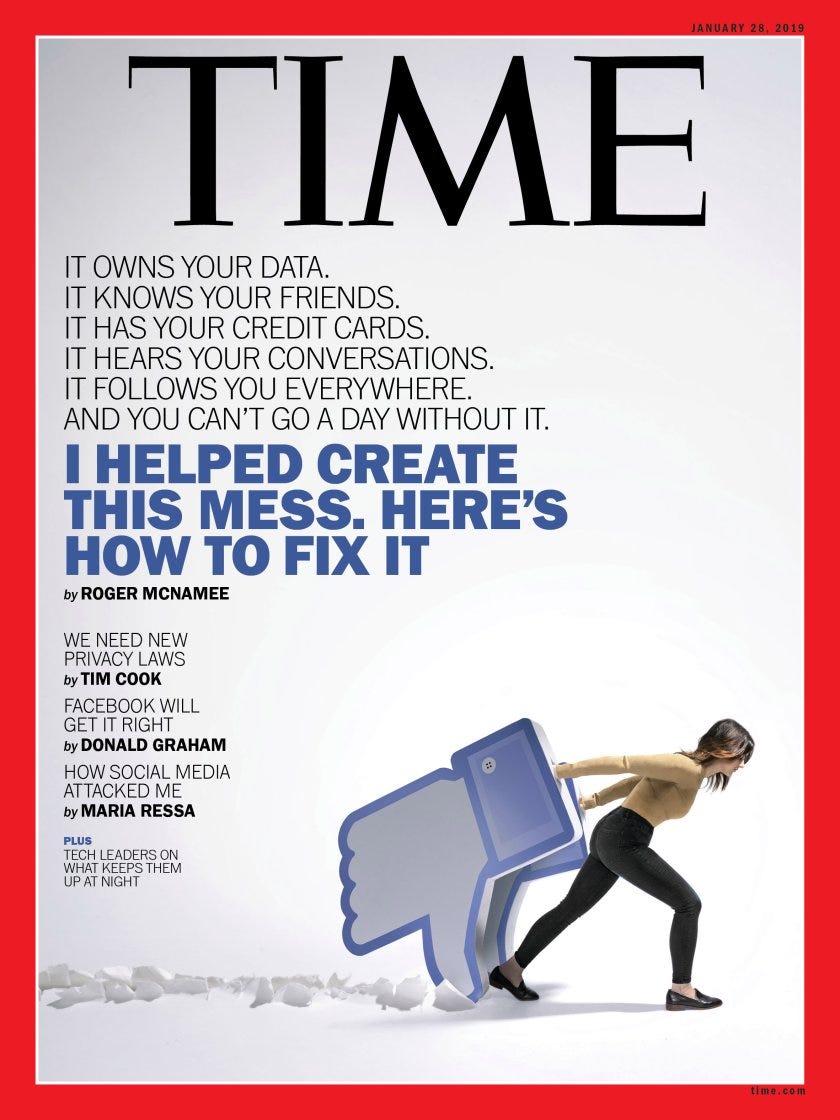

In the process of achieving critical mass, the heavyweights of Web 2.0 also exposed the Internet’s Original Sin: advertising.

Well, not ‘advertising’ per se, but business models that were based on rounding up users within private digital enclosures so that some omnipotent algorithm could conveniently sort them by location, age, gender, hobbies, political affiliation - you name it - for the benefit of corporate marketers.

Internet companies had stumbled upon the most lucrative of business models - the acquisition and monetisation of user data. Prospectors in the gold rush had found their gold, only it was buried in bits not atoms.

Many of these Web 2.0 successes were now being guided by the same North Star. It was perhaps inevitable that this arms race for data would result in a catalogue of perverse product decision designed to widen the microscope on unsuspecting users. Internet companies were now incentivised to use every cheap trick in the book to keep their users engaged and, more precisely, to keep us Hooked. They played to our deepest fears and ideological differences. They tacitly enabled pithy gossip and clickbait headlines. They ushered us in to their neurological casinos, offering cheap dopamine hits and instant escapism. They designed user interfaces and newsfeeds that resembled video games and slot machines. In effect, they became masters of the human psyche, creating products that were Irresistible.

The more time we spent on a particular platform, the greater the data trail we’d leave behind. The more actions and reactions they could draw from us, the richer the profile they could create for advertisers.

More and more players entered the digital arena employing novel ways to wrangle our attention and keep it for themselves. The companies that dominated the Web 2.0 era would defend their territory by making it difficult for you to travel seamlessly across platforms, increasing the costs of switching to a different network. The Facebook ‘you’ was different from the Twitter ‘you’ or the Snapchat ‘you’. You couldn’t just port all of your Snapchat streaks into Twitter, or seamlessly transfer your Instagram clout to your Youtube channel. You couldn’t take all of the data that Amazon had about you (your data) and just move it to Netflix. Hell, you couldn’t even take your game avatars and high scores from Fortnite and test them in within a PUBG battleground.

Switching over meant starting from scratch. This was savvy strategy, because the more time you spent on Fortnite, the less time you would spend on Netflix or TikTok.

The vision of the Internet as a borderless prairie was now being threatened by corporations that wanted to use this land to build their private enclosures. Although created on a foundation of public digital infrastructure, the Internet had, in effect, become privatised. Individuals weren’t in the driving seat. Corporations had come to rule the web. You didn’t own your identity. You didn’t own your data. And you certainly didn’t own your time and attention.

And that, my friends, is how we got here.

But its not where we’re going.

The next era of the Internet is already here. It is made up of a number of disparate parts, many of which are ready to go, many more still a work-in-progress. We’ve had one foot in this new world for the last decade. In fact, pop culture has already bestowed a classy name on this umbrella of technologies that will make up Web 3.0.

The Meta-what?

"We are called to be architects of the future, not its victims. The challenge is to make the world work for 100% of humanity in the shortest possible time, with spontaneous cooperation and without ecological damage or disadvantage of anyone."

–R. Buckminster Fuller

The side effects of Web 2.0 have made the Internet an easy target for many in the West who cast a suspicious eye on innovations that push us deeper into our screens. It is undeniable that the flourishing of the Social Web has left humanity with several teething problems that we’re still figuring out. However it would also be foolish to let these issues distract us from the infinite and profound ways the Internet has enriched the lives of the vast majority of people in the world.

Having the luxury to dwell on the unintended pathologies of the Internet is an example of what legendary VC Marc Andreessen refers to as ‘Reality Privilege’, articulating this so beautifully in a recent interview that the exchange is worth including here in its entirety:

The digital genie cannot be returned to the lamp. So the way forward is not to suppress our attempts at virtual innovation but to find a better way to co-exist with the Internet. Other groundbreaking inventions like the automobile and airplane similarly needed to iterate their way to discovering the right interface that would derive their best use. We needed to envisage important jigsaw pieces like roads, airports, runways, traffic lights, steering wheels, navigation systems etc to complete the puzzle and see the full picture.

The Internet now has a chance at a do-over. A chance to learn from the past and revisit the founding principles of the web from the lens of our current technological capabilities. The goal is to rectify the missteps of Web 2.0 while amplifying the best parts of the Internet.

Web 3.0 will usher in the next phase of humanity as a networked species by:

Reducing the friction between our online and offline selves via the emergence of naturally immersive technologies like Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR)

Inviting more meaningful connections between people through shared spatial awareness and richer sensory experiences that take place within persistent virtual worlds (eg: Fortnite, Decentraland, Facebook Horizon)

Re-architecting the Internet on the back of open source software and trustless crypto protocols, moulding the foundations of an interoperable Web that challenges the walled gardens of today’s tech giants

Restoring the control of personal identity and data back to individual citizens instead of corporations, while heralding an age of virtual avatars and pseudonymous digital identities that safeguard the privacy of individuals

Giving anyone with an Internet connection unprecedented access to participate in all manner of socio-economic activity anywhere in the world without the consent of traditional gatekeepers by leveraging permissionless blockchain-based networks

Catalysing a renaissance of artistic output by forging a direct link between creators and their audiences on the Internet, enabling new business models for the former while allowing the latter to have a tangible stake in the success of their favourite illustrators, musicians, writers and gamers via Non Fungible Tokens (NFTs)

Each of these components represent individual constellations in a galaxy that now has an official moniker - the Metaverse. The name traces back its origins to Neal Stephenson’s iconic 90s sci-fi novel Snow Crash, containing a mix of two words - ‘meta’ (meaning beyond) and ‘universe’. In the book, the Metaverse is described as a shared virtual world that can be accessed using special goggles, where people interact with their surroundings using digital ‘avatars’ of themselves. Something like this:

“As Hiro approaches the Street, he sees two young couples, probably using their parents' computers for a double date in the Metaverse, climbing down out of Port Zero, which is the local port of entry and monorail stop. He is not seeing real people, of course. This is all a part of the moving illustration drawn by his computer according to specifications coming down the fiber-optic cable. The people are pieces of software called avatars. They are the audiovisual bodies that people use to communicate with each other in the Metaverse. Hiro's avatar is now on the Street, too, and if the couples coming off the monorail look over in his direction, they can see him, just as he's seeing them. They could strike up a conversation: Hiro in the U-Stor-It in L.A. and the four teenagers probably on a couch in a suburb of Chicago, each with their own laptop. But they probably won't talk to each other, any more than they would in Reality.”

The ‘Metaverse’ has emerged as the leading contender to describe the blend of technologies that will produce the next iteration of the Internet. It is the collective name for the hardware, software and content that will liberate the Internet from 2D screens and inject it into our surroundings through a veil of virtual and augmented reality. Its final form will likely be a fusion of virtual reality, virtual currencies, digital goods, digital avatars, and countless other elements that make up the ‘observable digital universe’.

There is, however, a key ingredient that infuses the components described above with a consistent flavour, and that is 'Decentralisation’. One of the underlying promises of the Metaverse is to correct the balance of power that currently exists between centralised platforms (like Facebook, Google, Apple, Amazon etc) and the rest of the Internet.

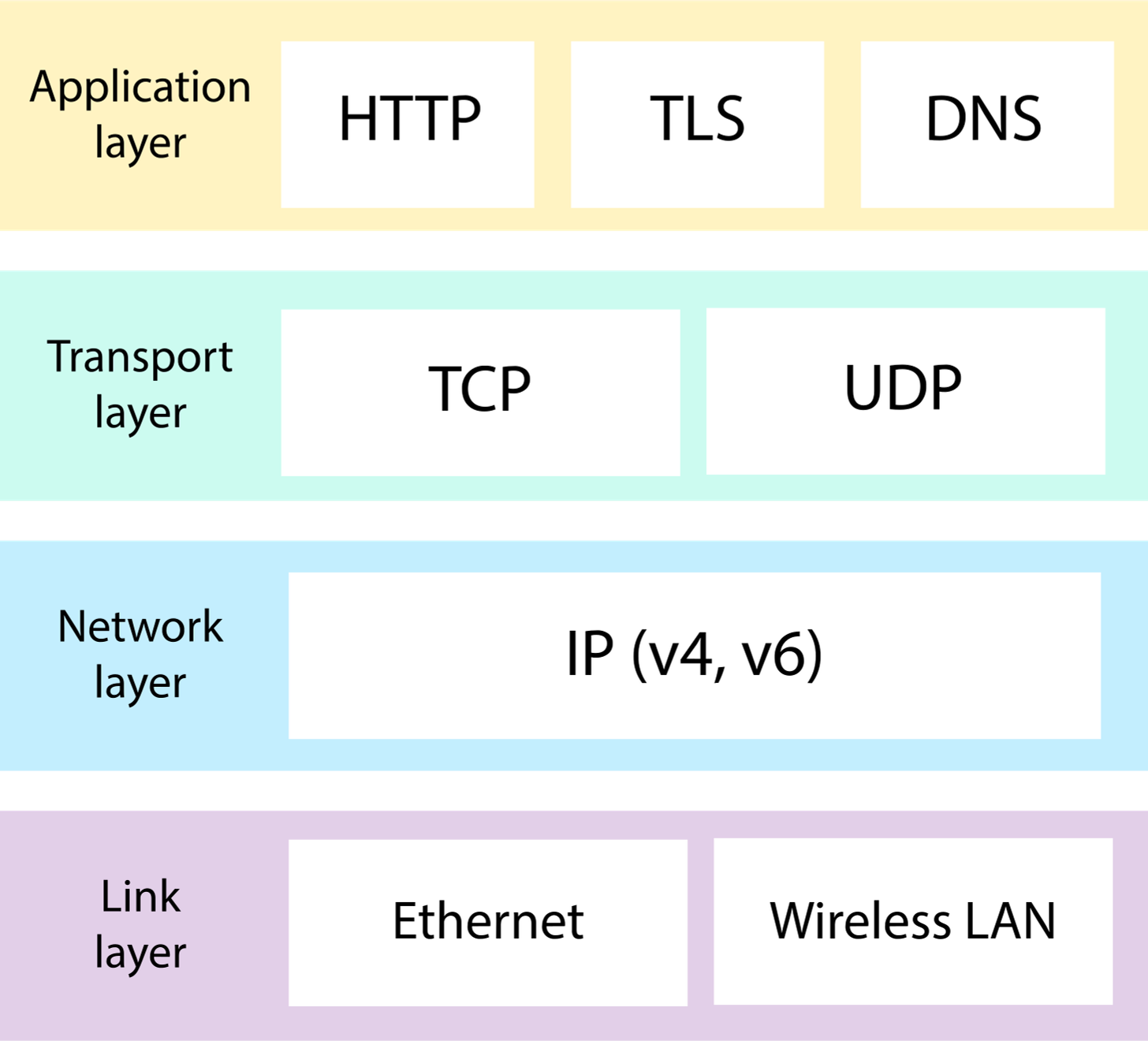

To understand why this is important, we have to revisit the founding principles of the Web. Its worth mentioning here that the Internet and the World Wide Web are not the same thing (though they’re often used interchangeably). The Internet is the physical plumbing (i.e. the cables and infrastructure) that connects computers around the world. The World Wide Web is the dominant information system used to store and access data on the Internet. The former was the critical innovation that unleashed the full potential of the latter. The original architects of the Web proposed a set of shared standards and rules for data transfer that would effectively create a common language of communication between computers on the Internet.

This would enshrine ‘interoperability’ as one of the fundamental building blocks of the commercial Internet. This meant that, for example, regardless of which browser you were using to access the Web, your computer would use the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) to retrieve your desired web page from another computer connected to the Internet. Similarly even if you and your friends were using different email clients (AOL, hotmail, gmail) you would still be able to send messages back and forth without any issues because all email applications are built on top of the Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP).

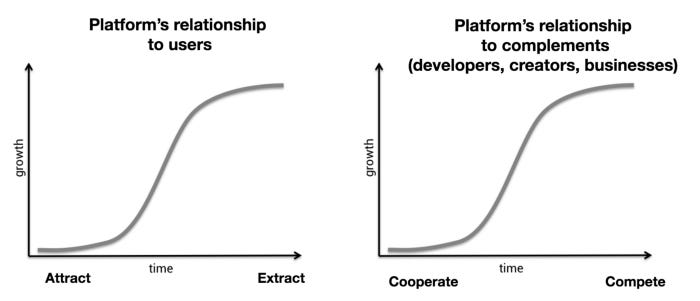

The interoperability enabled by this set of open standards and protocols is what lets different computers, applications and operating systems use the Internet in harmony. The fact that no corporation owned these protocols (they were collectively governed by independent non-profit organisations) meant that individuals, businesses and governments could invest their time and energy to build on top of this shared digital infrastructure knowing that ‘the rules of the game wouldn’t change later on’. But this decentralised version 1.0 of the Web eventually gave way to the domination of Web 2.0 giants.

Big Tech made the Internet user-friendly. The Googles and Facebooks of the world became so good at providing digital services that they eventually replaced the open protocols that they were built on to become the main access points for individuals and businesses that wanted to use the Internet. The iOS and Android app stores similarly became the twin guardians of the mobile web. Although these companies provided Internet users with sophisticated services that were often free* (in exchange for their data in most cases), the situation left us at the mercy of a small coterie of omnipotent decision makers.

Because of the importance of their companies to the functioning of the modern world, we have unknowingly uplifted these unelected officials to positions of worrying influence over our society. Aside from the fake news, the bots, the election manipulation, the data harvesting etc you have to trust that these platforms won’t randomly change their rules in a way that jeopardises your identity, your reputation, your audience, or your profits. For individuals, developers, and entrepreneurs, this is not an ideal state. People have no ownership over their online selves. You have to be wary of doing or saying something that could get you censored or de-platformed. Businesses have to take a leap of faith by building their castles on borrowed turf, lest they do something to piss off their benevolent masters. Innovation ceases to be a fair fight when the battleground is owned by your competitors.

And that’s why Decentralisation matters.

So what does this have to do with the Metaverse? Well, for starters, the Metaverse will not be constructed on the shifting sands of Web 2.0. Sure, members of the old guard will each try their hand at creating a captive (i.e. Closed) Metaverse. And yes, it is likely that the hardware we use to access VR and AR will come from familiar names. These are companies with industrial pedigree, with an advantageous position owing to their deep R&D budgets, longer time horizons for innovation, and economies of scale (Facebook’s Oculus, Microsoft’s Hololens and HTC’s Vive are leading candidates to capture the VR headset market; Nvidia and Qualcomm want to create the chips that power advanced AR and VR features etc).

But for the most part the Metaverse will be a democratically imagined digital nation composed of other democratically imagined digital nations. It will hopefully be Open. This belief mainly stems from the fact that over the last decade we’ve identified a way to incentivise open-source software development over the Internet. We’ve discovered a proven way to coordinate resources in the direction of cutting edge innovation at the protocol level. This set of ideas represent perhaps the most important technological development of our lifetime. They will embody the economic heart of this new Web 3.0 frontier. Ironically, this master key that unlocks the door to the Metaverse was forged in the fires of the 2008 Financial Crisis.

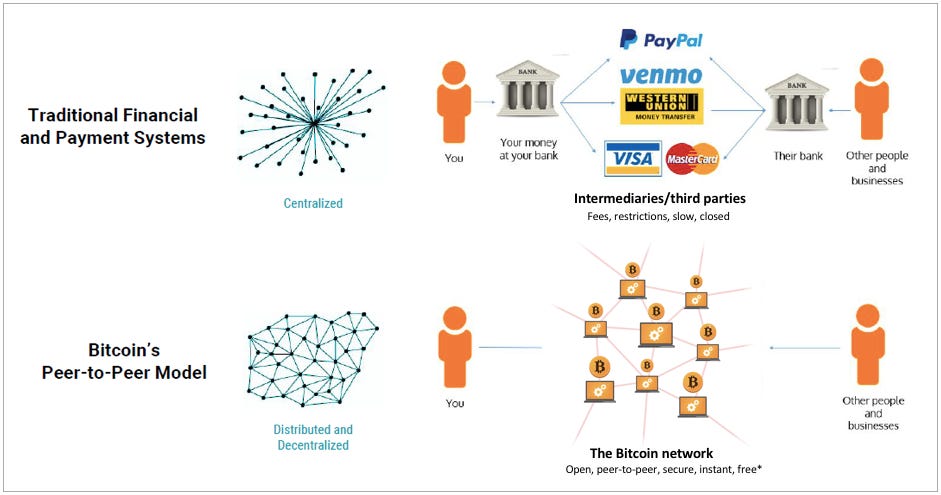

In October 2008, a person (or group) using the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto published a 9-page document in an obscure online mailing list that would have profound implications on the future of the Internet and, by extension, the future of humanity. In this whitepaper he (or she) laid out the foundations of a monetary system for the Internet that could function without the need for central intermediaries like banks and payment networks. This was based around idea that sending money over the Internet should be no different than sending an email - both processes involved bits of data moving through cyberspace. There was no actual movement of cash involved but for some reason ‘cross border’ payments involved lengthy settlement times and costly fees, even though in theory this process should have been no different than sending a ‘cross border’ email (which was instant and free).

Satoshi theorised that much of the time and costs associated with our traditional financial and payment systems were a result of a lack of trust between counterparties. For instance, in our current financial set up, banks maintain central systems of record with balances of individual and enterprise accounts. When someone initiates an international transaction, the sender’s bank and receiver’s bank update the respective balance of debits and credits in their copy of the record, and tally this record with each other to make sure the numbers match. They get a healthy fee for performing this service, safeguarding both parties from any kind of counterparty risk by ensuring that the terms of the transaction are duly satisfied. At the same time the payment networks used to facilitate the transaction (Visa, Mastercard, or native bank networks) extract their own service fee for enabling the movement of money (again, for facilitating the movement of data from one computer to another).

Satoshi’s whitepaper proposed an alternative to this system. Instead of central parties maintaining records of transactions and balances, what if you could create a system where all participants in a network were connected to each other directly (peer-to-peer), where every node on this network maintained their own copy of the record i.e. a system of distributed ledgers instead of a central ledger? To go one step further, could you incentivise each of the participants in this network to maintain an authentic record of transactions and balances, essentially convincing them to play the role of decentralised auditors? Would you then be able to create an accurate historical account of activity occurring on this network? Could you really get strangers from all over the world to cooperate to ensure the integrity of this system despite not personally knowing each other’s identities or intentions? Could you replace the trust in people/institutions with a trust in code i.e. could you trust that the inherent contract embedded in the code that powered the system would work as intended?

And if you could provide a satisfactory answer to each of these questions, would we still need the old financial machinery?

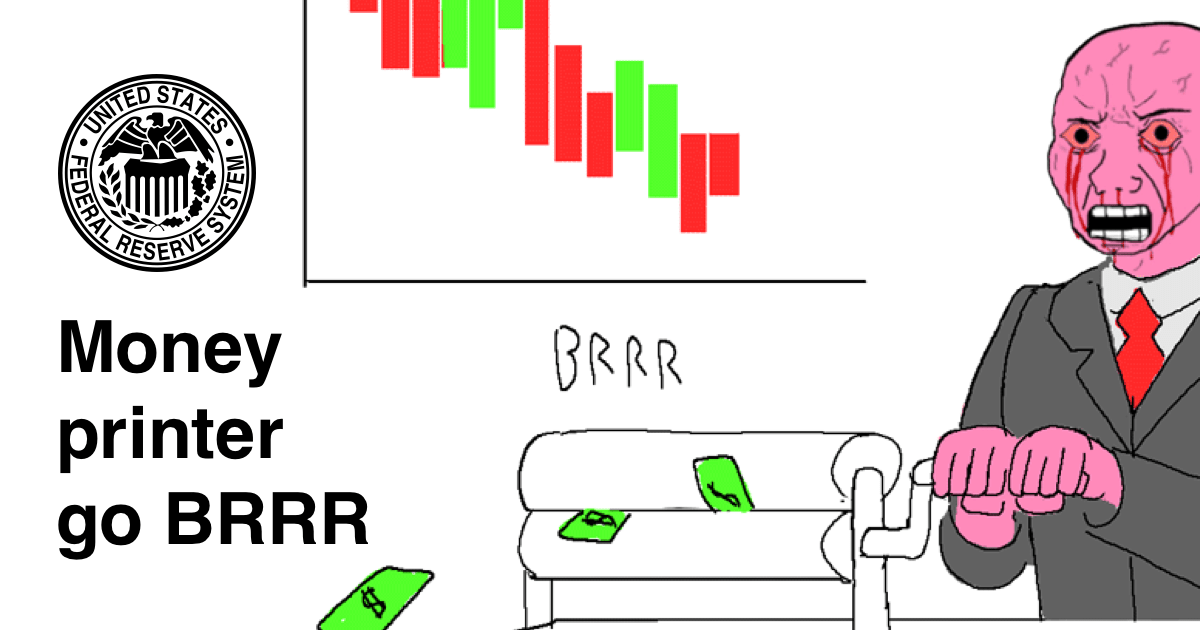

The Bitcoin network would open the door for a new type of monetary system based on cryptography (the art of encoding and decoding information) instead of central banks. It would popularise the use of an accounting system for digital asset known as a blockchain (because transactions are recorded in a series of batches or ‘blocks’). Blockchains provide an innovative mechanism for parties that don’t trust each other to agree on the contents of a database, or simply to agree on the state of a network or a set of facts. Bitcoin would also launch an entirely new class of assets called cryptocurrencies (or crypto assets) that would come to compete with ‘real world’ fiat money. Here’s the difference - the former is a product of cryptographic proof-of-work (i.e. created in the process of expending computing power) and its value is determined by the free market. The latter is a product of central bank issuance, where value must be injected into this paper currency in the form of a central government guarantee.

Three months after he first published his whitepaper, Satoshi had written up the source code for this system and released it for anyone on the Internet to inspect and download. And so, the Bitcoin network was officially born. 12 years later this network has over 100 million total participants, and the free market has bestowed its native currency (bitcoin) with a market cap of close to $1 trillion. Early believers have been rewarded for their faith by seeing the price of bitcoin rise from $0.0008 in 2009 to a peak of $64,863 in April 2021 as more and more people buy in to the bitcoin story.

The nuances of how bitcoin works are beyond the scope of this essay. However there are a few important conceptual and technological breakthroughs stemming from the success of bitcoin that are worth understanding in order to appreciate the opportunities presented by Web 3.0 and the open Metaverse:

1. Distributed network governance - there are more than 100 million addresses on the bitcoin network. The vast majority of people using this network have no knowledge of the identity of the other people on this network. In fact, your ‘identity’ on this network is represented only by a random string of letters and numbers as opposed to typical identifiers like your name or email. And yet it works. Satoshi succeeded in laying the blueprint for a ‘trustless’ protocol, where clever incentives would be baked into the rules of the game so that people all over the world could use this system to transact, store their wealth and earn bitcoin, safe in the knowledge that everyone would be acting in the best interest of the system because in effect that also meant they were acting in their own self interest as well.

We now had a template to create globally distributed systems for use cases besides digital money, where unknown participants could allocate resources and coordinate with each other to achieve an economic goal without needing to know or trust one another. You didn’t have to trust people when you could just trust the code instead.

2. Provable digital scarcity - one of the breakthroughs facilitated by bitcoin was in solving a tricky issue called the ‘double-spend’ problem, which had confounded many other efforts at creating digital cash systems online. The Internet had essentially reduced the marginal cost of replicating and sharing content down to zero. This made it difficult to verify the authenticity of any single file or unit of media (eg: you could make infinite copies of meme to share with your friends over email without anyone knowing which was the original file). For someone trying to ensure the economic integrity of an online monetary system, you can see why this might be a problem. How do you ensure that someone doesn’t just make infinite copies of a digital dollar? How do you ensure that the the same dollar isn’t spent in multiple places at the same time? How would a system with infinite replicability be able to hold any value?

Well, Satoshi’s system of distributed ledgers (the blockchain) ensured that you could trace the movement of every single bitcoin throughout the entire history of the Bitcoin network. This meant that if someone tried spending the same bitcoin in two places, the network would reject the second transaction as invalid if it discovered that the token had already been spent somewhere else. Satoshi also programmed the network so that there would only ever be 21 million bitcoin in existence. The creation, ownership and transfer of each bitcoin could be accurately tracked by anyone on the network using this distributed ledger technology.

Blockchains have given us a way to verify the authenticity and scarcity of a digital asset online at a time when modern monetary regimes are resorting to indiscriminate printing of money as a cheat code to stimulate their economies. Fixed supply vs infinite supply - which is the more robust monetary system? Which one is likely to increase in value with increased demand? Where would you rather hold your savings?🤔

3. Native digital assets - Bitcoin only exists on the Internet. You can’t print out a physical bitcoin. And yet it continues to acquire and hold monetary value in ‘real world’ dollar terms. This paradox is typically used by naysayers and boomers to dismiss bitcoin as a ponzi scheme, a fugazi, magic internet money, fairy dust, tulips, beanie babies etc etc. It is difficult to recalibrate one’s worldview to acknowledge that something that isn’t tangible can also be valuable. But that is mostly a failure of imagination. A Facebook ‘like’ has value but isn’t tangible. A video game high score has value but isn’t tangible. Today we are co-inhabitants of a borderless digital world called the Internet which has its own customs, symbols and stores of value.

The idea of provably scarce native digital assets that are created on and for consumption specifically on the Internet will soon become commonplace. Along with digital assets, you now have the idea of digital ‘ownership’ too. Contrary to your facebook account or even your email address, you actually own your bitcoin. No corporation or government can delete your profile or suspend your account. If you are in sole possession of your private key (i.e. the password to your bitcoin wallet) nobody else can take your bitcoin from you. Cryptocurrencies are a transition from digital participation to verifiable digital ownership. This will extend to other unique, natively digital products too.

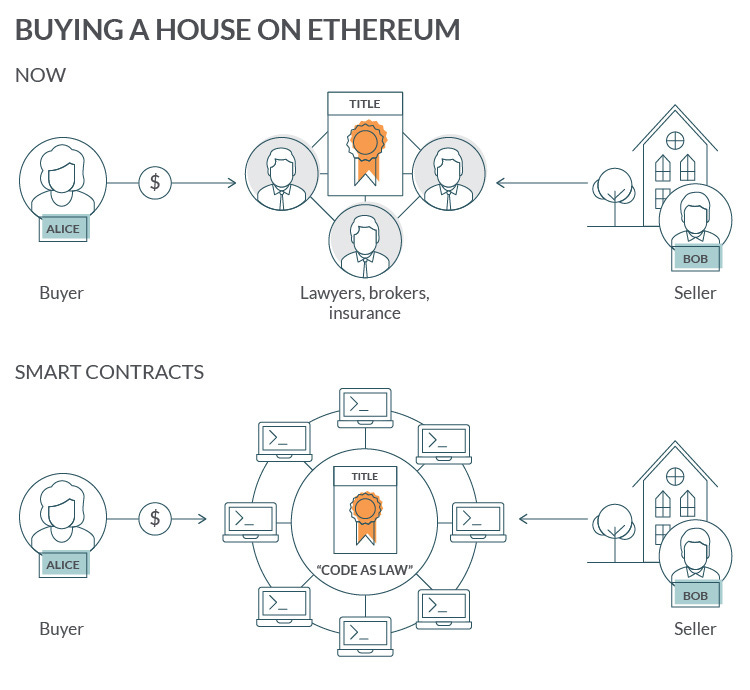

4. Programmable money - The rules of the bitcoin network are written into its code. There is an inherent ‘contract’ that participants implicitly sign up for when they’re using the bitcoin network, almost similar to entering the border of a new country. The agreements enshrined in this contract govern how the system works, how rewards are given out, what counts as a valid transaction etc. There’s no need for lawyers or auditors to check whether these terms have been met. The contract automatically self-executes on the satisfaction of pre-defined conditions (eg: if I can provide a digital signature that corresponds to the wallet address where my bitcoin is held, then I have the right to send that bitcoin to anyone on the network). These automated digital agreements stored in code are known as ‘smart contracts’. They allow money to become ‘programmable’ through the attachment of pre-defined conditions.

This is a powerful idea when abstracted to other use cases. It means you could prescribe the business logic for a system or a commercial deal where the terms of a contract could be programmatically tied to the satisfaction of pre-set criteria, without needing any kind of arbitration from third parties. Eg: I could create a token on a blockchain that represents a piece of digital art where I would receive a perpetual 1% royalty every time the token was transferred to another wallet address. The possibilities of programmable money to cut out the time and cost of manual arbitration while expanding the surface area of digital commerce are endless.

5. Decentralised finance - Anyone with an Internet connection can be part of the Bitcoin network. The bitcoin software is free to download. The code is there to be inspected. Anyone with a bitcoin wallet can own bitcoin and make transactions on the network. No single entity controls bitcoin. You don’t need the blessing of any corporation or government to take part in what is basically a parallel financial system for the Internet. The Bitcoin network is a collection of disparate users, investors and developers all trusting that the code will work as intended, that the rules of the game will be respected. No central body can censor your transactions or your prevent you from making a payment if you can prove that your bitcoin belongs to you. You don’t need any kind of accreditation or license to be part of the network. It is true monetary sovereignty. The same principles can be extended to a decentralised credit system, or a decentralised fundraising mechanism, or a way to generate decentralised yield. The era of open, borderless, trust-less, permission-less finance that began with bitcoin is now in full bloom. All you need is an Internet connection.

Phew. That was a lot to take in. If you’re still with me, you’ve earned yourself a 🍪

Anyway, the genesis of bitcoin sparked a Cambrian explosion of innovation in the field of blockchain technology and crypto assets. Talented entrepreneurs and developers from all over the world hoped to capture lightning in a bottle by experimenting with new decentralised protocols, echoing the raw ambition and chutzpah of early Internet pioneers.

Bitcoin proved that you could tokenise value and transfer it over the Internet without the need for central intermediaries. With the right system architecture, a decentralised network could be incentivised to keep an accurate record of transfers and ownership of a tokenised asset. The system was elegant in its design, but the use case was quite simple - a native currency for the Internet i.e. an asset that would function as a store of value, a medium of exchange and a unit of account for the digital age. But what if you took the same ingredients and used it for other, more complex applications? In the last decade numerous blockchain platforms have emerged that allow you to create and execute your own smart contracts, building on the learnings from Bitcoin. Chief amongst these new platforms is Ethereum.

Ethereum has come to play the role of a virtual computer sitting on top of the Internet. It is a Turing-complete computing platform which means it can be used to solve any kind of computational problem (unlike Bitcoin). In terms of technological complexity, if Bitcoin is a calculator then Ethereum is a smartphone. People from around the world use the Ethereum platform to collaborate on open source development of decentralised applications. In turn they can create projects that issue native tokens which could represent digital currencies (like bitcoin), digital products (like video game items), digital commodities (like computing storage or computing power) or even digital representations of real world assets (like diamonds, equities or real estate). Ethereum itself is a decentralised protocol too. Control of the network rests in the hands of users and holders of its native token ‘Ether’, rather than any central figure like a CEO or President.

In theory you could design something as complex as the decentralised version of Uber, where drivers and riders would be connected with each other directly without a central party taking a fee. The network could be capitalised with an initial token offering (instead of an IPO), where early believers could help seed the development costs of the network hoping to get rich if the price of the token increases as more drivers and riders join the network.

You could create a decentralised social network where users were incentivised to find and remove fake news.

You could create a decentralised video game where users could create their own weapons and costumes.

You could create a decentralised music streaming service, where artists could directly upload their music and get a tokenised fee from users every time someone played their songs.

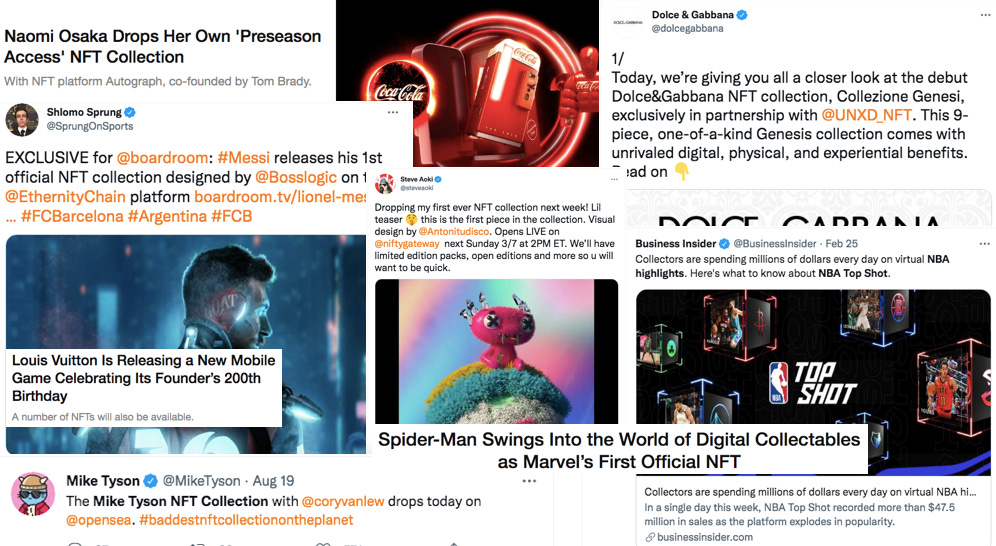

Ethereum’s greatest gift might actually be the popularisation of a token standard called ERC-721, which is effectively a template to represent unique digital items on the Ethereum blockchain. This means that unlike bitcoin or ether which are fungible tokens (all tokens are the same, you can exchange these 1:1), ERC-721 can be used to create tokens that are unique i.e. tokens that are non-fungible. The benefit of creating a non-fungible token (NFT) on Ethereum is that you can establish a cryptographic proof of creation, ownership and transfer of a unique digital asset as a matter of public record. The same way that bitcoin helped to install provable scarcity for online money by solving the double-spend problem, NFTs are a way to prove the existence and authenticity of ALL digital content online. The arrival of NFTs as a new form of digital media means that we can now ascribe value to things like memes, illustrations, tweets, event passes, music, and even blogposts in a way we previously never could.

It should come as little surprise that in 2021, NFTs officially went mainstream.

Bitcoin, Ethereum, NFTs, and other decentralised protocols and applications are the main reason why an ‘open’ Metaverse represents an attainable goal. In 2008 Satoshi had originally outlined the need for bitcoin as a financial innovation in his whitepaper. But the success of cryptocurrencies have had far reaching political and social ramifications as well. The creation of money, the conferring of value, the safeguarding of personal property…neither is restricted to the monopolistic domain of traditional power structures. The zany world of blockchains and crypto assets has captured the imagination of dreamers everywhere who would dare to imagine a world where the gatekeepers of finance, art, social networks, and government wield considerably less sway over our day to day lives than they do now. That world has every chance to be built on the pristine terrain of a decentralised Web 3.0.

So to recap:

On Web 1.0, internet users were passive consumers of static content. On Web 2.0, the social media invited individuals to become dynamic content producers themselves. Web 3.0 will orchestrate an even greater change, where everyday Internet users will have the chance to become content and media owners via crypto tokens and NFTs

Web 1.0 was the ‘read-only’ web. Web 2.0 is the ‘read-write’ web. With the increasing importance of open, permission-less, trust-less decentralised networks, Web 3.0 will become the ‘read-write-execute’ web.

So far our experiences with the Internet have mostly been restricted to 2D interfaces. With the hardware industry now having made it through several cycles of innovation and iteration, the next phase of the web will be optimally experienced in Virtual and Augmented Reality via a persistent, live, shared digital universe that we will refer to as the Metaverse.

In Web 2.0, value gravitated towards scale. Global social networks, more connections and followers, infinite replication and sharing of media etc. In Web 3.0, value will come from scarcity. The focus will shift to tighter-knit online communities, more meaningful connections with smaller social circles, and investment theses based on crypto assets that have a finite supply.

Web 2.0 was a transition from physical to digitised, where we attempted to replicate our offline routines in an online setting. Web 3.0 will facilitate a more significant change from digitised to natively digital. There will be products, services, status symbols and experiences that have no analogue in the ‘real world’ and can only be experienced and utilised on the Internet.

Crypto networks and NFTs will provide the interoperable lubricant between apps, games, websites and VR worlds, reducing the switching costs between platforms and consequently threatening the power base of Big Tech. Web 3.0 will foster direct peer-to-peer connections between participants in a market, the rules of which will be written and enforced in code, reducing the rent-seeking capabilities of Web 2.0 intermediaries. Individual artists, creators, gamers etc will be able to capture a much larger chunk of the value they generate online, with greater control over their identity and data.

Now for the fun stuff

What does all this mean for you?

“For a bunch of hairless apes, we've actually managed to invent some pretty incredible things.”

― Ernest Cline (Ready Player One)

The Internet is a cocoon that holds the secrets to our metamorphosis as a species. The more elaborate its design, the greater the unpredictability of our final form.

This essay might be the first time you’ve come across the word ‘Metaverse’. However, the truth is every time you immerse yourself in any kind of digital activity on any kind of electronic device you’re essentially commuting from the physical world to the digital one. You’re already a regular visitor to the Metaverse. Our 2D interfaces are not the most comfortable form of travel, but the good news is that we’ll all be entitled to an upgrade in the next few years.

Rory Sutherland (Vice Chairman of the Ogilvy Group) coined the term ‘psychological moonshots’ to describe how you can influence the quality of people’s lives far more significantly by provoking changes in their perception rather than changes in their physical reality. For example, if your objective is to reduce the travel time of passenger trains, you can achieve a greater level of success by introducing free wifi than you can by inventing trains that are marginally faster. Psychological moonshots are a better, cheaper way of changing people’s lives.

So, even if we’re still a few years away from having universal, accessible VR experiences, once you realise that you already possess dual citizenship of the physical and virtual worlds, you can realign yourself to take advantage of the opportunities presented by the Metaverse.

So what do you need to know?

1. Reset

If you’ve dipped your toes into the world of cryptocurrencies then you’ve likely been red-pilled already.

Bitcoin (as a social experiment) launched a philosophical inquiry into the nature and validity of our existing democratic hierarchies, asking uncomfortable questions like:

Do we still need central totems of power if decentralised networks can validate the ownership of private property at a fraction of the socioeconomic cost?

Do we need the blessing of central governments to assign ‘value’ to a currency? Do we still need central banks to manage monetary systems?

In a capitalist set-up, should money be subject to the same competitive forces as any other product or service? Should people get the freedom to decide which ‘money’ they think is most valuable?

Should our governments automatically import their control of the physical domain to the Metaverse too?

If people are free to join a network that exists only on the Internet; where participation in this network comes with an implied agreement to abide by a codified set of laws; where belief in the ideals of this network are what give it value; and where property, identity and ownership are publicly recorded and safeguarded by this network, then to whom do we really owe our digital nationhood?

This line of inquiry is guaranteed to become a matter of public debate in the years to come. It is the reason why governments of developed nations today have such a queasy relationship with cryptocurrencies. They represent a fundamental threat to the status quo. They rip apart the old social contract.

In his seminal 1996 essay A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace, John Perry Barlow addressed governments of the industrial world, writing that “Cyberspace does not lie within your borders. Do not think that you can build it, as though it were a public construction project. You cannot. It is an act of nature and it grows itself through our collective actions.”

The point of highlighting this is to suggest that you will have to revise your belief systems to account for many seemingly absurd developments of the Metaverse Age, or at the very least have an open mind about the exotic value systems of this brave new world.

The idea that acquiring a high-profile NFT to use as your social media profile picture is a stronger indicator of status than a fancy watch or car because the surface area of online clout is significantly larger than that of your local neighbourhood.

Or that art and creativity are no longer the exclusive domain of human beings.

Or that reasonable people will spend their hard earned money to buy natively digital goods to decorate their natively digital habitats, identities and avatars.

![Culture] The boom of NFTs and the future of digital fashion | HFG Culture] The boom of NFTs and the future of digital fashion | HFG](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fda41cd08-d61f-4c21-af19-83f0e49841e0_1080x502.png)

Or that your ‘real world’ assets might lose their lustre once people realise they’re spending far more time in the virtual world than the physical world.

The limits of the Metaverse will be determined not by the laws of physics but by our imaginations. This is new territory and it can take some getting used to. But the best way to get educated is to get involved.

2. Participate

“Find out where the people are going and buy the land before they get there.”

- William Penn Adair

Alex Zhu is the founder of Musical.ly, the Chinese social media platform that took off because of the popularity of its short form lip-sync videos. Musical.ly was acquired by Bytedance in 2017, and is a core part of what eventually became social media giant TikTok. Zhu has a theory about creating new online communities. He explains that building a new social network is like discovering a new continent in the world. At first its difficult to attract people to this new land because there’s nothing of value there. So the first settlers are often individuals excited at the prospect of a fresh start. They often come from ‘lands’ which already have an established order and a well defined social hierarchy, which means ordinary people have little opportunity for upward mobility. They have nothing to lose by venturing out to find value in unchartered terrain. So to build a successful new network you need to make sure that a majority of the early wealth is distributed to the first explorers, because they can then serve as an example to the next wave of aspiring settlers. They provide evidence that the new world can be better than the old one.

This notion will be doubly true for the open Metaverse because blockchains are tools to bootstrap networks. They are networks on steroids. To quote Naval Ravikant, blockchains “will replace networks with markets”, and turn markets into economies. They are an open, democratic way to coordinate resources towards a desired goal. Crypto has been an unprecedented catalyst for generational wealth redistribution primarily because of its inherent promise to reward early believers of new ideas, to compensate those who took the risk of being first (and wrong). This mechanism is baked into the design of crypto networks. If there are enough people that can be convinced to support an idea, crypto protocols will provide the infrastructure to turn that idea into reality.

Building on decentralised platforms means that innovation need not wait for permission or buy-in (or funding) from any kind of central authority. Permission-less networks mean that for the first time ever, anyone with an Internet connection can help seed the next big tech idea. You don’t need to be a VC or an accredited investor or even have a minimum net worth to participate in the world of NFTs or decentralised finance (DeFi). Contrary to an Initial Public Offering which comes at the end of a company’s journey, crypto networks are available to the public at the earliest possible stage of ideation. It is high risk, high reward. But that is to be expected for a sector that is still only 12 years old.

Blockchain protocols are an open invitation to participate in the economic activity of the Metaverse. So how can you get involved?

Well, for starters, if you consider that a limited liability company (LLC) is just a collection of contracts and agreements, you start to understand why joint stock companies in the future will be able to exist solely in the form of code on a blockchain. This new concept of enterprise is known as a Decentralised Autonomous Organisation (DAO). It holds incredible promise for the kinds of ideas and efficiencies that can be achieved by automating the coordination of global economic and cognitive resources via the magic of code. Think about it, you can now be part of a ‘company’ on the Internet with millions of people from around the world that you’ve never met. You can get paid for carrying out your duty as per the terms of the smart contract. DAOs help to remove much of the administrative burden and central oversight that comes with running a large scale company today. You can expect to see this new species of organisation populating the commercial corridors of the Metaverse.

If you’re the type of person with an audience or a flair for creative output you could play around with Non-fungible Tokens (NFTs). Its difficult to overstate what a colossal impact NFTs will have on any (and every) creative field. This is no fad. NFTs sit at the fountainhead of a full blown modern renaissance - of art, finance, technology, investing and everything in between. This is the discovery of a new medium of expression akin to the popularisation of canvas as a base for paintings. The output from this world will be groundbreaking, breathtaking, lucrative, and offensive - everything that good art should be.

Cultural decentralisation has been a serendipitous by-product of monetary decentralisation. There are no rules to deny anyone the freedom to bend this new technology to their creative will. The same way that you have the freedom to participate in the next great decentralised enterprise, you have the same chance of discovering the next great NFT artist. Anyone is free to buy, collect, make and trade NFTs, which at their core are tokenised units of culture. Artists and owners of intellectual property have been given a generational opportunity to enter a new medium and commercialise their work. NFTs will become a staple of marketing and promotional programmes by brands and media houses too. The relationship between creators and their audiences is about to change in an astonishing way.

The era of cryptographic art is just getting started. If the ink of history is spilled on its walls and not its pages, NFTs are the graffiti of our time. To quote two of the titans of the NFT world, “the art of the Metaverse will be crucial, beautiful, digital, and cryptographical. And it will be stored on-chain”.

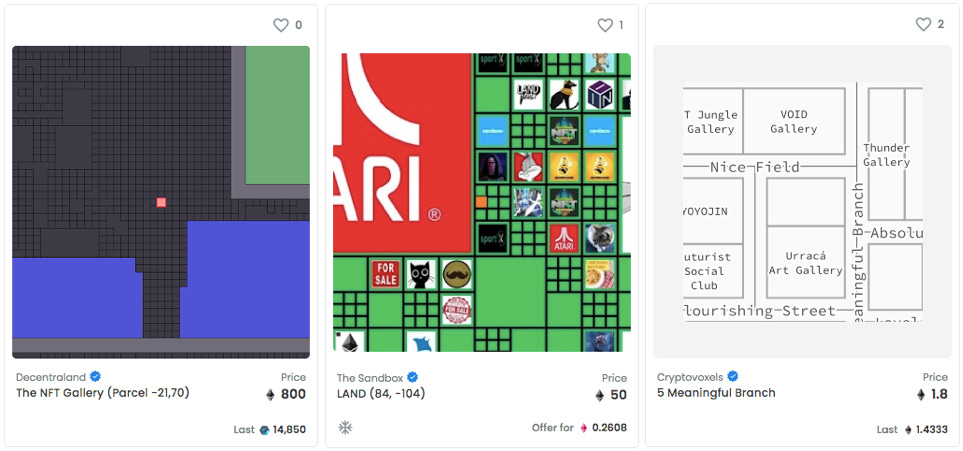

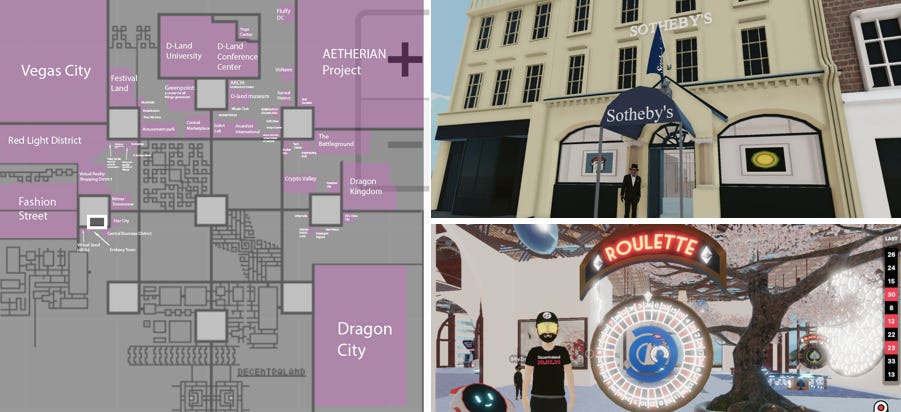

However the best way to experience the unfamiliar terrain of the Metaverse would be to take a tour of the leading open Metaverse platforms. Some of these are designed just for 2D (like Treeverse, or even older non-crypto titles like Roblox and Minecraft). Others have been created with a 3D future in mind (like Somnium Space and Victoria VR). And somewhere in between are virtual worlds like Decentraland, The Sandbox and CryptoVoxels whose final form is best experienced in 3D, but whose current 2D state reveals several clues as to what a fully realised Metaverse economy will look like. In particular there’s some pretty incredible stuff happening at the intersection of NFTs and virtual land.

For example, on Decentraland - which is also one of the earliest ‘virtual world’ projects in crypto - you can use its native token $MANA to buy NFTs that represent unique plots of virtual land each with a dimension of 16m x 16m. Like the real world, you can build commercial establishments on this land, you could design a ‘residential’ property for your digital avatar, you could lease out the land to other developers, or you could just hold on to it as an investment, hoping the value appreciates as more people learn about the project and get involved. Also similar to physical real estate, the parcels of land that are closest to areas of interest are more expensive.

Seeing as how digital scarcity is one of crypto’s most hallowed pillars, there will only ever be 90000 total parcels of land as per the design of the original Decentraland protocol (which is open source and can be inspected by anyone). So all the individuals that spotted the potential of virtual land without dismissing it as a frivolous plaything are now reaping the benefits of owning prime real estate in the Metaverse. Earlier this year a digital real estate company named Republic Realm made headlines for purchasing 259 parcels of land on Decentraland for $900,000, marking the largest and most lucrative investment in virtual land so far. Makes sense, right? Once we run out of physical space on earth, unless you’re Elon Musk, where else are you going to go? $900,000 might not get you much value in the busiest cities in the world. But on Decentraland it gets you prime real estate to build something that can be seen and visited by the entire world from the comfort of their homes, without the constraints of the laws of physics.

So if real estate in your hometown is too expensive, maybe you can ask your realtor to find you a plot on Decentraland or Somnium Space? This kind of question may sound silly now, but again it comes down to where you think you’re going to spend more of your time in the future. Where do you think you have the greater capacity to earn a living, have a social life, and be happy?

Things could get even more interesting when you add the potential of decentralised finance to a world of virtual real estate:

Are the wheels turning yet? Do you see why provable digital ownership and provable digital scarcity are such important breakthroughs? We can now ascribe possession and value to digital media, which means people can also extract value from their digital assets similar to how they would in the physical world.

Eitherway, as I’m sure you’ve realised by now, things are about to get very interesting. If you aren’t someone that pays attention to the whimsical rhythms of the crypto world, some of this sounds insane. I understand. But we’ve barely scratched the surface here.

If I was 18 today and plotting out my ideal career, I would try and visualise all the ways my chosen profession is likely to be Metavers-ified.

You want to be an architect? Hone your 3D modelling skills to the dimensions and requirements of different virtual worlds.

You want to be a designer? Well, it might be more lucrative and creatively challenging to imagine fashion for the digital realm (plus you don’t need to worry about costs of production or supply chain management, you can just go Direct-To-Avatar).

You want to be a talent manager? Maybe think about how you can create, manage and monetise a roster of virtual influencers?

If you’re already a lawyer, a teacher, an illustrator, a musician…it only takes a bit of imagination to visualise how our earthly vocations will manifest themselves in a collaborative 3D setting.

We have every reason to believe that the Metaverse will be an unprecedented global economic multiplier. I mean we’re literally creating multiple virtual worlds, each with their own virtual economies. Some will be mirrors of our current physical world, and others will be entirely new constructs. What is certain is that there will be opportunities for investment, employment and empowerment across the value chain of the Metaverse.

But there’s still room for fun and games.

3. Play

“The next big thing will start out looking like a toy”

- Chris Dixon

Video games have emerged as the closest natural predecessor to the Metaverse. In fact many of the distinguishing features of a future Metaverse are already commonplace in the most popular gaming titles of today like Fortnite, Roblox and Minecraft. Fortnite (the multi-platform battle royale phenomenon created by Epic Games) in particular has played a pivotal role in helping people get comfortable with the idea of collaborative virtual experiences.

Although it started out as a multiplayer online game, Fortnite today is a vibrant virtual world where players can:

take part in shared real-time global experiences like virtual concerts

use digital representations of themselves (avatars) to play and navigate the game environment

use pseudonyms or gamer names to identify themselves online

spend real world dollars to buy the game’s native currency ‘V-Bucks’

spend their V-Bucks on cosmetic items and costumes (skins) to signal differences in status and experience

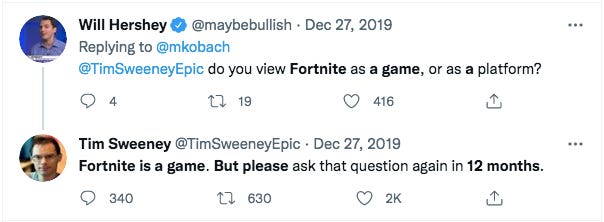

Today it has a total of 350 million registered players that regularly spend over 3 billion hours in the game every month. The sheers numbers it now boasts now has advertisers regularly tapping into the game to reach the coveted 18-35 audience. Fortnite in essence has transitioned from a game to a social network. And its CEO Tim Sweeney has acknowledged this metamorphosis too.

It has surpassed any other form of media to become Gen Z’s favourite place to hang out online. An entire generation of kids is growing up at ease with the concepts of virtual worlds, socialising online, virtual goods and pseudonymous digital avatars. And so they will become the first to embrace the quirks of the Metaverse as well. These are the future Masters of the Universe.

The difference between Fortnite and other conventional social networks is that Fornite didn’t need to bolt on elements of gamification to their platform in order to increase user stickiness. Its original goal (like any game) was just to create a fun, interactive experience online. That it turned into this global phenomenon is a marker of how stale the traditional Social Web has become. And that’s why the leading social networks of the future look more like games today (Decentraland, Cryptovoxels etc) than the typical feed-and-scroll interfaces that we’re accustomed to. Therein lies the promise of the Metaverse - socialising on the Internet will become a richer, more natural experience than the ‘like-comment-tag’ malaise that we find ourselves in today.

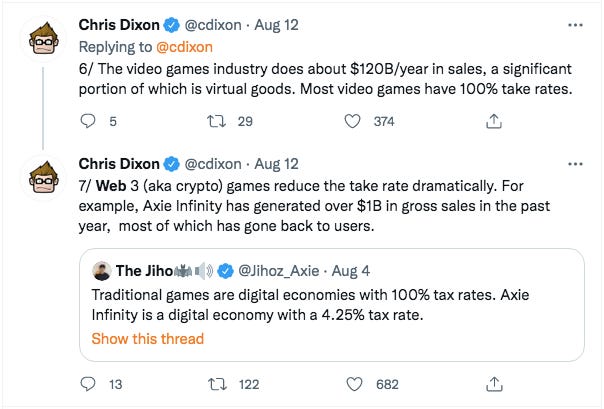

The problem with Fortnite is that it is still ensconced in the philosophy of Web 2.0, meaning that:

- V-Bucks are only legal tender within the Fortnite ecosystem

- Game items can only be used on characters in Fortnite

- Fortnite is the sole entity that can create skins, items etc for players to purchase

- Brands and businesses have to approach company executives if they want to create marketing campaigns for Fortnite

If you had to reimagine Fortnite for Web 3.0, it would look something like this:

- players would be able to own their avatars so they could transport these into different games outside of Fortnite

- game items would be built on interoperable crypto standards like ERC-721, allowing players to buy and sell these as NFTs on an open market, and transfer these assets from one game to another

- the in-game currency would also be a crypto token, making it a liquid asset that could be freely exchanged with fiat money. This would also mean that in-game accomplishments could be converted to real world dollars

That’s what Axie Infinity looks like. One of the biggest tech stories of 2021 has been the arrival of a new crypto-based gaming format called Play-To-Earn. The new wave has been led by a Pokemon-style online game named Axie Infinity where, just to illustrate the art of the possible:

- you can buy or breed NFTs that represent digital pets named Axies which can be bred, battled and traded both within and outside the game

- the game has two native tokens - AXS which can be used to take part in the governance of the platform, and SLP which is earned every time players battle, play, or use the game. Because these token have been created on Ethereum, they can be listed and traded on crypto exchanges, with a market price in dollars, meaning that in-game accomplishments can be translated to real world income. This incentivises even non-playing retail investors to buy and hold the tokens (and Axies) themselves as a form of investment

- Axie is also building its own virtual world Lunacia, which began auctioning off parcels of land in 2019 where players will be able to harvest rare in-game resources and dream up their own ways to impact and interact with the game

- you can also buy tokens in a DAO named Yield Guild Games (YGG) whose objective is to buy Axies and rent them out to players who can’t afford them, taking a share in the profits generated by players within the game.

The founding team behind Axie Infinity is based in the Phlippines (although for all intents and purposes it is now situated in the Internet itself). In the throes of the pandemic, one of the biggest stories to come out of this region was about how ordinary citizens were leaving their jobs in droves to make money playing Axie Infinity (and often making 4-5 times more than what they were making in their old jobs). It is possible for value to travel seamlessly from online to offline and back again - that’s the potential of Web 3.0.

The games of today will look like the social networks of tomorrow.

The games of tomorrow will look like the economies of today.

Closing thoughts

“Cyberspace. A consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators, in every nation, by children being taught mathematical concepts...a graphic representation of data abstracted from banks of every computer in the human system. Unthinkable complexity. Lines of light ranged in the nonspace of the mind, clusters and constellations of data. Like city lights, receding...”

- William Gibson, ‘Neuromancer’

Sci-fi writers play two important roles. They must spend half their time as entertainers and the other half as soothsayers, gazing into their crystal balls to catch a glimpse of humanity’s future. The job description demands competence in both the physical and fantastical worlds. The best stories exploit the writer’s artistic license to devise technological breakthroughs without the hindrance of scientific reality, allowing them to showcase novel ideas (and not people) as the main characters in their plot. In doing so science-fiction provides scientists, engineers and dreamers with a buffet of ideas to feast on. Farfetched as it may seem, the inspiration for modern inventions like the defibrillator, lab grown meat, submarines, space stations, driverless cars and even Google Maps can be traced back to the pages of sci-fi.

And so it will be for the Metaverse. Or the Multiverse. Or OASIS. Or Cyberspace. Or whatever you want to call it.

The idea of humans existing (or co-existing) in a digital realm has been an alluring draw for many of history’s most iconic sci-fi writers and film makers. Whether manifested explicitly or through analogy, there is an undeniable temptation to plot an escape from our physical shackles and take root in the realm of fantasy.

We assumed that a digitally immersive future would look like this:

But right now it kinda looks like this:

But very soon it’ll look like this:

The convergence of the physical and virtual world looms large. You only need to look at your weekly screen time to understand how much of you currently resides in meatspace vs cyberspace. One might seem ‘realer’ than the other for now, but chalk this up to a failure of imagination. The pandemic has revealed the true extent of our dependence on the Internet. ‘Work from home’ really means ‘work from the internet’, which will soon mean ‘work from the Metaverse’.

We’ve had one foot in the Metaverse for as long as we’ve had screens, and certainly for as long as the Internet has been around.

The details of a physical-digital convergence will unfold in the years to come. We will collectively be challenged by thorny questions like:

what is the ideal human form in such a world?

what values of the ‘old’ world should we keep? which ones should we discard?

how rich should our sensory experiences be? how much is too much?

what would keep us busy? what would keep us entertained?

who actually owns this place?

Tim Urban, founder of the online blog Wait But Why, once coined the term 'Die Progress Unit’ (DPU) to quantify ‘how many years one would need to go into the future such that the ensuing shock from the level of progress would kill you’. He was riffing on Ray Kurzweil’s Law of Accelerating Returns which poses that ‘advanced societies have the ability to progress at a faster rate than less advanced societies because they’re more advanced’. At the current pace of advancement in hardware and software, we could find ourselves eclipsing the innovation from the first two eras of the Internet by the end of this decade. Our DPU sits somewhere between 12-15 years by my calculation.

This next phase of the Internet will forever change the way we live, work and play. I fully expect to see the size of the Metaverse economy exceed that of our current one within our lifetimes. Our worlds are about to become richer, weirder and infinitely more complex. Pay attention to your screen time, because any week now you could find yourself waking up in the Metaverse. Hopefully that won’t be such a bad thing.

MORE METAVERSE STUFF

Matthew Ball’s excellent 8-part primer on the Metaverse

Packy McCormick’s piece on the Value Chain of the Open Metaverse

Erik Torenberg’s blogpost about Living on the Internet

Juan Benet’s presentation on Web 3

Beau Cronin’s blogpost on Unbundling Reality

Chris Dixon’s blogpost on Why Decentralization Matters

Cuy Sheffield’s piece for a16z on “Fantasy Hollywood” — Crypto and Community-Owned Characters

Ryan Gill is the co-founder of Crucible, a start-up thats building tools for individuals to create and own their identity in the Metaverse (starting with the world of gaming). They are committed to the principles of an ‘open’ metaverse and want to design solutions that prioritise the autonomy of end users. Ryan is also one of the most lucid thinkers and vocal champions of this new frontier. His tweets, podcasts and Clubhouse appearances have been a key resource in helping to shaping my own understanding of this space.

Books worth reading - ‘The Sovereign Individual’ by James Dale Davidson, ‘Who Owns the Future’ by Jaron Lanier, ‘Ready Player One’ by Ernest Cline, ‘Snow Crash’ by Neal Stephenson, and ‘Neuromancer’ by William Gibson

It took me a month to write this thing. If you made it all the way here and you thought this was a good use of your time, why not take a couple of seconds and share this post?

Or if you want to yell at me for writing blogposts that are too long, you can find me on Twitter at @RahulSanghi1

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rahul Sanghi recently left his position at Visa, where he had served as the company’s Fintech Lead for India & South Asia since December 2020. He began his career as a consultant with KPMG in London, spending a majority of his time helping the firm set up its global enterprise blockchain and crypto asset advisory practice. He moved back to India in 2018 and joined Koinex (then India’s largest cryptocurrency exchange) as Director of Business and Strategy, before assuming the same role at B2B SaaS-startup FloBiz. Rahul is now focused on finding magic at the intersection of crypto and the creator economy. He doesn’t know why he’s writing this in third person, but whatever.

Spectacular piece!

Mind-blowing. This is an epic article, reminded me of Mahabharata put in a tech context. It's my first read. You spent a month writing, I may require more than a month to completely imbibe the contents. What a lucid way to explain the most advanced technology. Kudos you deserve an Oscar