Hey everyone👋

Welcome to the 445 new Tigerfeathers subscribers who’ve joined since our last piece. Its getting crowded in here folks. I think we’re going to make it.

If you haven’t joined the party yet, here’s your chance. All new subscribers get 10 free days of good luck. What do you have to lose?

To kick things off this week, a small personal/professional update from me. As long time readers of Tigerfeathers know, since December of last year I’ve spent a majority of my (professional) life serving as Visa’s Fintech Lead for India and South Asia. A couple of months ago I made the decision to focus 100% of my time going forward to building out this newsletter as the first piece of a much larger jigsaw puzzle. We started Tigerfeathers last year as a fun side hustle that would allow us to explore our love of tech and writing. Our experience (and the support of this incredible community❤️) over the last 12 months has convinced me that its time to go all in.

Why?

1. Because I’m not that smart

2. Because I don’t make the best decisions

3. Because I think there’s something special happening at the intersection of Web3 and the creator economy, and I want to be part of it

The pandemic has accelerated several converging digital trends that would have otherwise taken decades to fully materialise. Legacy institutions across every industry are now regularly being usurped by individuals who intuitively understand how to bend the internet to their will. These are creators of media, software, art, and (crypto) finance who are mastering the rules of the Great Online Game, employing a variety of tools and tricks to sneak past the gatekeepers of their chosen fields.

In fact, today’s piece is about a young institution in India that embodies the best of this new world - ‘A Junior VC’, or as they’re popularly known - ‘AJVC’.

AJVC is a tricky customer to cover, because it doesn’t really fit into any conventional organisational avatar, which is what makes their story so compelling. AJVC isn’t a commercial entity (even though it creates and distributes a number of products). It doesn’t generate any profit (even though it has all the makings of a potentially lucrative business). In many ways it resembles a publisher, given its devoted audience and vast range of editorial output. Members of the AJVC team themselves say that it is both a platform and an incubator, one that could eventually take the shape of a Venture Capital fund or even a Distributed Autonomous Organisation (DAO).

However, for now AJVC is best described as a kaleidoscope of content and community, the kind of entity that will become commonplace in the next era of the internet, making the AJVC story one of the best case studies on how to build a Web3 media brand.

Over the last three years, AJVC has come to represent a bustling oasis of knowledge within the Indian startup landscape. Part lighthouse, part playground. Their unique vantage point has allowed this amorphous group of enthusiasts to acquire considerable leverage in the corridors of India’s tech ecosystem. If you’re a founder or investor operating in India, you’re probably familiar with them already. If not, then you’re in luck.

To properly contextualise AJVC’s place in India’s startup odyssey, today’s essay is divided into three major sections that can each be read as a standalone mini-essay:

Part 1: We kick off with a tour through India’s economic history leading up to our arrival as a bonafide global startup hub

Part 2: We dive into the origin story of AJVC and how they’ve successfully scaled a passion project into a trusted consumer brand

Part 3: We look at AJVC through a Web3 lens to understand what makes it a textbook incarnation of a Web3 media brand (i.e. a Metamedia brand)

So without further ado…

If you were coming of age in India in the late 1980s and especially early 90s, you had front row seats to the restoration of the Great Indian Dream. India had spent the first four decades since Independence in a make-or-break quest for self discovery. As a young democracy with a chance to find its feet for the first time, the priority of our founding fathers had been to stabilise a national foundation that was still reeling from the scars of a multi-decade struggle for Independence.

“In India, the sapling was planted by the nation’s founders, who lived long enough (and worked hard enough) to nurture it to adulthood. Those who came afterwards could disturb and degrade the tree of democracy but, try as they might, could not uproot or destroy it.”

― Ramachandra Guha (India After Gandhi: The History of the World's Largest Democracy)

India itself is a study in contradiction - a polychromatic portrait of language, caste and religion, a spectrum of ambition and survival, a dance of capitalism and socialism, both a principal and prisoner of its geography. The notion of a united India was always a question and never a guarantee, which is why our nation’s first leaders prioritised the instilling of a unified national and social identity, to help define for the first time what it meant to be Indian. Post-independence India was a patchwork quilt of diverse groups and interests which had been stitched together for the first time, often threatening to split at the seams. Sir John Strachey, member of the Governor General’s Council in the British Raj, articulated the challenge of governing India in a speech at Cambridge in 1888, remarking that “Scotland is more like Spain than Bengal is like the Punjab.” That an independent India endures and shines today is both a triumph and an aberration of conventional historical wisdom.

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, tasked with leading India’s first government, had to navigate a minefield of thorny issues (like the division of states on linguistic grounds, the succession of India’s princely kingdoms, the delineation of a national border, the creation of a foreign policy and the drafting of India’s Constitution) any of which could have torpedoed the vision of a free and independent India. Governance required a delicate touch. The orchestra needed to be carefully directed, lest the dissension of any single member sink the entire performance.

This need for meticulous planning and control extended to the design of our economic policy as well. Nehru recognised that an India rife with poverty and inequality would ultimately be a volatile India. Unleashing the power of the free market before we had political or social stability would be a recipe for disaster, or so it was reasoned. The fear was that unfettered capitalism would lead to the exploitation of a vulnerable Indian populace, only 12% of which was literate and 80% of which still lived under the poverty line at the time of Independence. The Prime Minister wanted to ensure that as we carved a path forward for the first time, it was our responsibility to ensure that no Indian was left behind. And so we picked our poison - a Soviet-inspired era of Five-Year Plans that placed the Centre at the ‘commanding heights of the economy’.

Writing in India Unbound, Gurucharan Das recounted that:

The commitment to socialism and central planning resulted in a four-decade stranglehold on the spirit of entrepreneurship in India. It meant that India would spend the latter half of the 20th century as a spectator in the global economic arena, content to sit back and watch as our Asian counterparts like Taiwan and South Korea announced themselves as legitimate players on the global stage. While our neighbours spent their own post-Independence eras developing technological, manufacturing and export capabilities, our philosophy of insular protectionism resulted in a 44-year economic hibernation.

To succeed as an entrepreneur in post-Independence India, you required much more than just business acumen. You also needed the dexterity of a gymnast to manoeuvre around the spools of red tape that had been laid out by the pernicious License Raj. You needed the bushcraft of an explorer to navigate your way through the political corridors of New Delhi. You needed the generosity of a patron saint to get comfortable with sharing your hard-earned profits with the Centre in the form of a full menu of taxes, fines and penalties. Most of all, you needed the patience of a Shaolin monk while you waited for overdue policy changes to be enacted and approvals to be granted by a myriad of government agencies before you embarked on any commercial activity, lest you found yourself flouting one of the infinite draconian measures that had been enshrined in outdated legislative frameworks. Entrepreneurship in India was as much an exercise in commerce as it was in masochism.

By the end of the 1980s, starved of foreign investment and competition, hamstrung by a government intent on monopolising industrial development, with a Balance-of-Payments crisis looming fast in the horizon, it appeared that the Indian experiment was running out of time.

Independence v2.0

“No power on earth can stop an idea whose time has come…Let the whole world hear it loud and clear. India is now wide awake.”

- Manmohan Singh, Finance Minister of India, in the Budget Session of the Indian Parliament on 24 July, 1991

When India’s then Finance Minister (and future Prime Minister) invoked the iconic words of Victor Hugo, the ‘idea’ he was referring to wasn’t capitalism or even the liberalisation of the economy - he was referring to the idea of India, an idea that had so far failed to deliver on its immense promise.

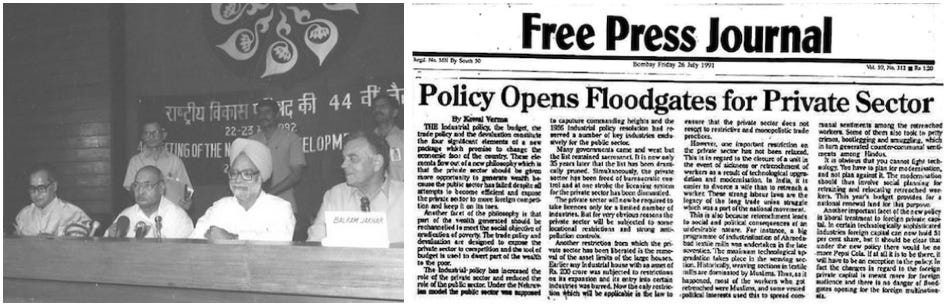

In a landmark session of the Lok Sabha during a presentation of the Annual Budget in July ‘91, with the blessing and support of Prime Minister PV Narasimha Rao, Dr. Manmohan Singh would go on to announce a slew of industrial reforms designed to jolt the Indian economy from its slumber and kick-start the engine of capitalism in the subcontinent.

The message was clear - India had opened for business.

The protagonists of liberalisation, led by Dr. Singh, sought to inject entrepreneurial energy into the system via a blueprint of incremental and radical policy changes. In a series of bold brushstrokes, the image of India’s corporate, industrial and trade landscape was remodelled overnight. Some of the major changes introduced over the course of the Budget week in July 1991 included:

the immediate devaluation of the Indian rupee by ~20% in order to aid the competitiveness of Indian goods abroad

the ‘opening’ up of the Indian economy by embracing a philosophy of free trade, introducing incentives for exporters and reducing tariffs on the import of foreign goods (an issue that had become so contentious that economist Ankit Mital even pointed out that ‘for at least three decades, most Bollywood villains were smugglers—people who import without a licence’)

abolishing the archaic policy of industrial licensing for all but 18 industries (except those with a social security risk like cigarettes, alcohol etc), thus freeing 80% of Indian industry from the nettles of the License Raj

repealing the Monopolies & Restrictive Trade Practices (MRTP) Act that had thwarted the ambitions of Indian companies by requiring a litany of approvals for any attempt at expanding or diversifying their industrial capabilities (eg: for opening a specialised bank branch, for installing a new machine at a factory etc)

reducing the number of sectors that had been reserved for Public enterprise from 17 to 8 (only leaving aside the areas that had strategic or security ramifications like railways, atomic energy, arms and ammunition etc), inviting private sector participation into previously untapped corners of India’s economy

several measures to attract foreign investment into India, most notably announcing a list of high tech and high priority industries which didn’t need any additional permissions to solicit Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) upto a certain limit. The newly hospitable environment for national and international commerce sparked the rapid entry of foreign brands that are now part of the furniture in India. It also stirred Indian entrepreneurs into action.

Change of this magnitude doesn’t happen overnight. Although seen as radical at the time, the greatest testimony to the exigence of the New Industrial Policy is that despite the tribalism endemic to Indian politics, each successive government since then has endeavoured to continue in the tradition of liberalisation. Sure, there’s been the occasional bout of resistance and the odd hiccup, but for the most part Indian leaders have recognised that private enterprise, foreign investment and global competition are key supplements to a well-nourished economy.

After dragging its feet for the best part of 44 years, the liberalisation of 1991 represented a small step in the right direction for the Indian economy, which would erupt into a full blown sprint by the time the ink dried on the pages of the next three decades.

India: The Millennial

The legacy of the 1991 reforms cannot be overstated. It isn’t easy to change the economic DNA of an entire nation with just a few strokes of a pen, but it is harder still to change the mindset of a populace that had become disillusioned by four decades of bureaucratic sloth. John Locke, philosophising in the 1600s, mused that if you really wanted to change the way people behave in society, it is far more effective to change fashion than it is to change the laws. People need to see for themselves that it is ok to be or do something different from the prevailing norm.

The Indian state machinery had taken a bold and historic step to lead Indian entrepreneurs to the trough of capitalism, but would they drink?

J.K. Galbraith, a distinguished economist who served as the 7th United States Ambassador to India, had once observed that “The Indian commitment to the semantics of socialism is at least as deep as ours to the semantics of free enterprise…Even the most intransigent Indian capitalist may observe on occasion that he is really a socialist at heart.” But the story of Indian enterprise (and Indian consumers) in the late 90s and early 2000s tells a different story.

Any way you measure it, the summer of ‘91 marked a turning point for India. The early spoils of a post-Independence economy had largely gone to the industrialists and traders that were quickest to exploit the country’s vast buffet of natural resources. Legacy business houses like the Tatas (cotton), Mahindras (steel), Reliance (polyester) and others had established formidable empires in the 20th century on the back of ventures that were originally set up to manufacture or trade commodities. Homegrown consumer brands had also begun to emerge over the same time period (Asian Paints, Bata, Bajaj Auto etc), embedding themselves into public consciousness via the increasing commercialisation and pervasiveness of television and radio within Indian homes. Savvy Indian engineers had sniffed the opportunity to provide foreign companies with cut-price software development, manifesting in the incorporation of Indian tech giants like Infosys, TCS and Wipro in the late 1980s. However the next generation of Indian entrepreneurs had been gifted a much wider economic canvas on which to express their ambitions. In particular, the 1991 reforms had exposed much of the ‘softer’ side of the Indian economy for the very first time.

India’s first Prime Minister had always maintained that a commitment to science and technology was the catalyst that would allow a young nation to extract a demographic dividend from its vast population, one that was still finding its feet in the modern world.

“It is science alone that can solve the problems of hunger and poverty, of insanitation and illiteracy, of superstition and deadening custom and tradition, of vast resources running to waste, or a rich country inhabited by starving people... Who indeed could afford to ignore science today? At every turn we have to seek its aid... The future belongs to science and those who make friends with science”.

- Jawaharlal Nehru in the Indian Parliament (1953)

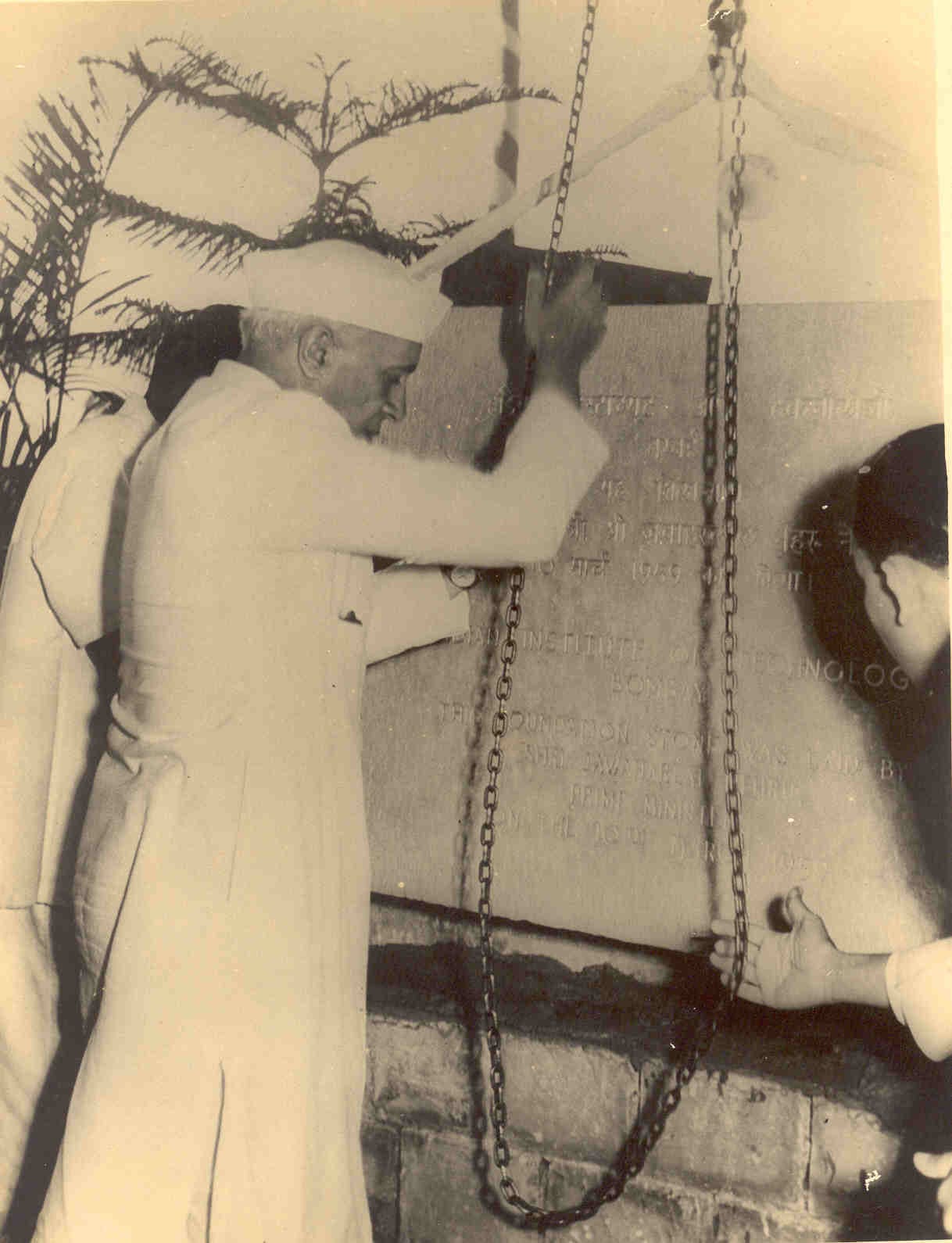

One of his most enduring legacies is the stewardship of the Indian Institute of Technology Act in 1956, which advocated for the setting up of higher technical institutions of national importance in all four corners of the country. The hope was that these universities, modelled on the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the US, would be a bastion of India’s research and engineering capabilities, helping to unearth and nurture the brightest technical minds in the country. In 1950, at the inauguration of the first IIT in Kharagpur (West Bengal) built on the site of a former colonial detention camp, Nehru declared that “Here in the place of that Hijli Detention Camp stands the fine monument of India, representing India's urges, India's future in the making. This picture seems to me symbolical of the changes that are coming to India”.

In hindsight, it shouldn’t be a surprise that the land that gave the world the ‘zero’ would feel at home in the realm of bits and bytes. With Nehru championing India’s quest for technological prowess, national institutions like the IITs began churning out engineers and scientists of the highest calibre that would become respected (and demanded) the world over. One of the greatest tragedies of the License Raj was that some of our brightest potential entrepreneurs would go on to settle oversees in search of opportunities to commercialise their talent. Thomas Friedman estimated that since 1953 almost 25000 IIT graduates have emigrated to the US, going on to make an impact as developers, CEOs and founders of American tech companies. The summer of ‘91 would put the brakes on this unfortunate brain drain.

The drawbridge to the castle of private enterprise had been conspicuously lowered for the first time. With it, the percentage of Indian tech grads settling abroad dropped from 70% pre-liberalisation to just 30% by 2006. Why leave if the seeds of entrepreneurship could now be sown on fertile ground at home? The services sector was just opening up, and the arrival of the commercial Internet in India in 1995 meant that the global race for software supremacy was also in full swing. Suddenly the career path for an Indian professional could take several different routes.

Motivated by profit, ambitious Indians could seek opportunities to engage in a wide spectrum of economic activities within industries (old and new) that were now open to private players.

They could look to expand traditional family-owned businesses that were now encouraged to take risks, experiment and innovate, free from the interference and involvement of the Central government.

Indian dreamers were incentivised to set up joint ventures and solicit investment from foreign brands that wanted a piece of the action in India.

Indian graduates could now cut their teeth at professionally-run homegrown companies instead of competing in a Squid Game-esque race to occupy a meagre number of open positions in the wasteland of India’s creaking public sector.

Indians had now been given the gift of choice. Capitalism was no longer a sin, it was a game to be played. Entrepreneurship had become aspirational. The change in law had helped to usher a change in fashion, which in turn led to a change in behaviour.

Gurucharan Das summarised the metamorphosis of the Indian psyche in the 1990s and early 2000s, writing in India Unbound that:

So what next?

Flipping The Script

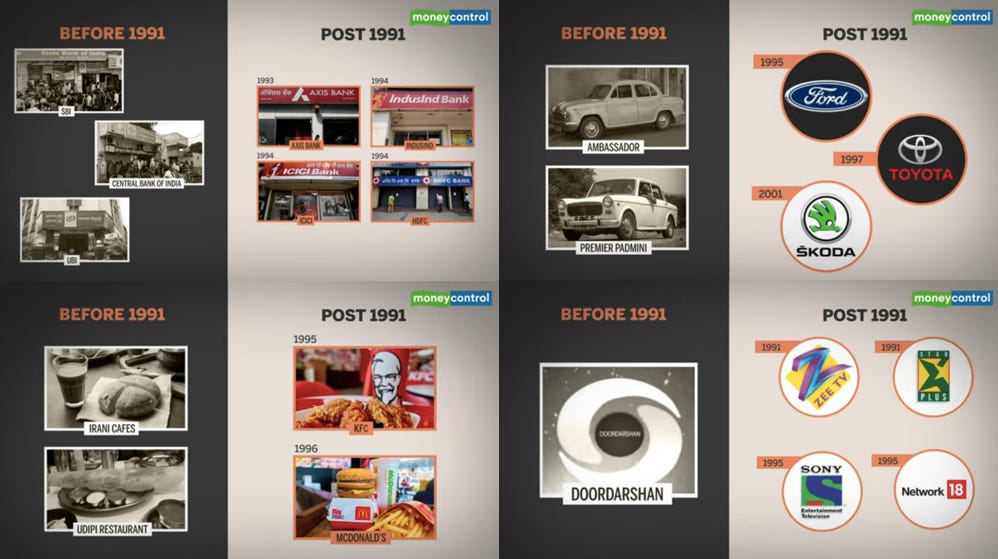

Liberalisation would unleash the pent up entrepreneurial energy that had been brewing in several areas of the economy including retail, aviation, hospitality, banking and finance, telecom, information and technology, consumer goods and healthcare. We tend to think of startups today as little squares on our smartphones but the companies launched in the late 90s and 00s laid the brick-and-mortar foundation for a productive and sustainable Indian economy. It became common in the 2000s to read newspaper headlines of Indian companies expanding oversees and even shopping for foreign acquisitions, something that would have seemed absurd to anyone paying attention to India in the 20th century.

“I think Indian society has been a better ambassador of India than the Indian state. For too long the public sector presented an image of India that was arrogant, verbose, ideological, and closed to the world. In particular, the Indian private sector has represented the true India—pragmatic, forward-looking, diverse, open to the world”.

- Fareed Zakaria, Indian-born journalist and former editor of Newsweek International and editor-at-large of Time Magazine, in 2005

The 2000s would also see the true dawn of the Indian Internet era. Although the Internet was first introduced in India in 1986, it took almost a decade longer for VSNL to make it available to the general public. We had seen Indian entrepreneurs in the late 90s and early 00s have early success with the fledgling Internet. Some notables include Sanjeev Bhikchandani launching jobs portal Naukri.com in 1997 or Deep Kalra founding travel booking website MakeMyTrip.com in 2000. The Indian Railways became the first government department to use a website as a core part of service delivery, offering online ticket bookings from 2001 onwards. At the same time homegrown heavyweights like Infosys, Wipro and TCS were helping to shine a global spotlight on the capabilities of Indian software engineers.

But for the most part we were following the lead of Western nations who had marked themselves out as superior product developers that were setting the standard for innovation in software (Microsoft, Oracle etc) and hardware (Apple, IBM, HP etc). The fact that their populations were historically further along in their economic journeys meant that their citizens could also be the first to take advantage of new technologies like broadband connections, e-commerce, online payments or cellular phones. That equation is now being flipped around.

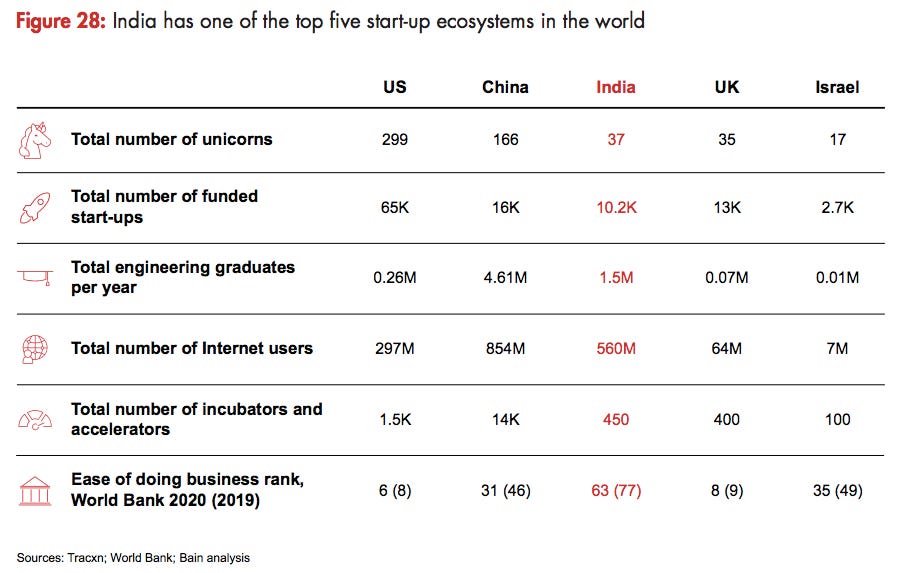

Our country now boasts one of the most vibrant tech and startup communities anywhere on the planet. If software is eating the world, India has proved to be the most sumptuous of dishes. Thirty years after liberalisation, startups in India have moved from the back pages to the front pages. Indian entrepreneurs have earned their moment in the spotlight. In a curious way, the present Indian growth story is analogous to the economic journey of another global superpower - the United States.

In the 1900s, American civilisation was reconstructed around a single invention - the automobile. The car was seen as a prerequisite to enjoying personal autonomy, key to one’s freedom of movement and the ability to access employment, recreation and public services. The arrival of the automobile in American society triggered a wave of entrepreneurship, job creation and industrial development in order to meet the demand for roads, highways, auto parts and fuel, along with a blossoming of hotels, restaurants, amusement parks and other services to cater to the whims of an American public that was now constantly on the move. The automobile provoked a reconfiguration of existing laws and regulations, as well as a modernisation of prevailing technological standards. Its safe to say that Uncle Sam’s journey to the 21st century would have been far bumpier without the Ford Model-T.

India in the 2000s and 2010s was similarly remodelled around a single invention - the smartphone. In the blink of an eye, we went from a country where you had to wait more than 10 years for a landline telephone connection to one where over 744 million Indians now access the Internet everyday through their smartphones. We went from sky high telecom rates to affordable phones, 4G internet speeds, and bottom-of-the-barrel data prices ($0.09 for 1GB of mobile data in India vs $8 in the United States). Instead of building roads and highways, we turned to public digital infrastructure as a way to improve connectivity for Indian citizens. India’s digital revolution was supercharged by a universal identity programme (Aadhaar) and an interoperable mobile payments platform (UPI) that sought to give every Indian the ability to participate in the emerging digital economy.

With social media adding another log to the bonfire of globalisation, Indians now had access to the best and brightest minds in the world. Indian consumers could now use applications built in Silicon Valley. They could be inspired by ideas from Twitter and aspire towards lifestyles on Instagram (for better and worse). Indian businesses also had to adapt to a new medium of commerce which meant that Indian entrepreneurs would have to raise their game to compete with global tech behemoths, thereby becoming world-class craftsman of product and software in their own right. Investors, both local and foreign, quickly mobilised the tools and funds they needed to capitalise on this gold rush.

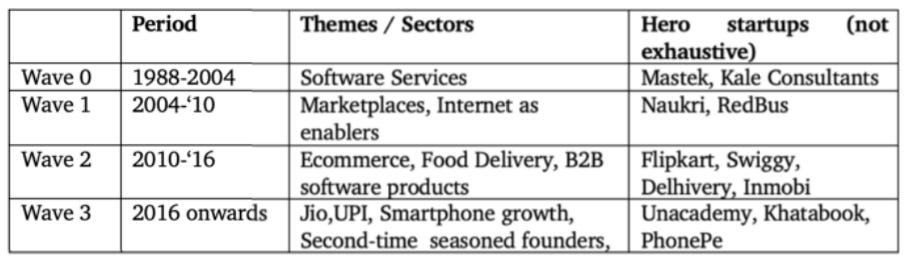

The smartphone would shepherd India into what Sajith Pai (VC, Blume Ventures) defines as the ‘third wave’ of India’s startup evolution:

He writes that “An interesting theme in Wave 3 is the emergence of the seasoned founder, well-versed with launching and scaling software products; these seasoned founders include second-time founders as well as CXOs (product, engg, biz dev) from hyperscaling, well-funded startups. These seasoned founders found — and continue to find — it easier to source funding, close rounds faster, typically at higher valuations than first-time founders, and scale faster”. Because of the Internet, this next generation of founders is arriving at the front lines of enterprise armed with technical and domain expertise like never before, faithfully acquired at the church of Jobs, Musk, Bansal, Kamath, Shekhar Sharma and others. They find a market flush with capital that is more open to ideas, more forgiving of failure, and more comfortable with risk. The training wheels have well and truly come off.

Startups have now entered the wider cultural bloodstream in India.

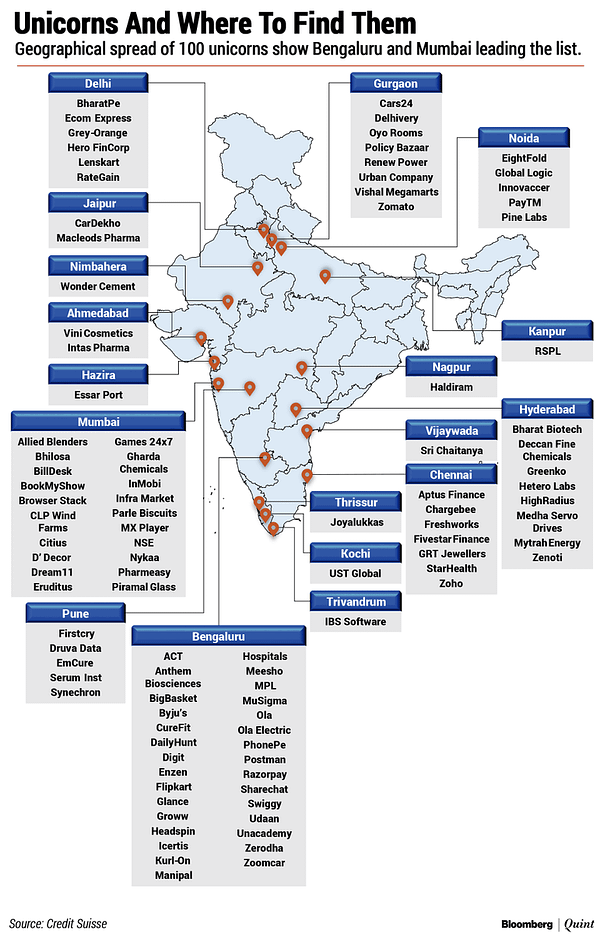

They’re hitting escape-velocity faster than ever before.

They’re coming from all over the country.

Demonstrating proof that they can go the distance.

Which means that the eyes of the investing world have turned to the Subcontinent.

All of which adds up to an entrepreneurial frenzy the likes of which our country has never seen before. Startups are invading college campuses to snatch away talented graduates. White collar professionals are transitioning from secure tenures at blue chip MNC’s to the unpredictable world of emerging tech. The all-action nature of this space - funding announcements, exits, IPOs - has given the mainstream media a new toy to play with. Starting up is no longer restricted to a certain age, background or qualification - entrepreneurial Indians have been given the ultimate green light to make a leap of faith.

India has taken a uniquely winding road to get to this point. It has taken time for Indian consumers to get comfortable with the act of ordering food, buying a dress, hailing a cab or availing a loan online. It has taken hard work to convince global enterprise to trust Indian software products. It has taken a generation for small business owners to replace paper and pen with application and screen. It is heartwarming to see homegrown consumer brands now stand shoulder-to-shoulder with their global counterparts. Buying (or using) Indian isn’t a compromise anymore, its an edge.

You see, it is relatively easy to create the necessary frameworks and institutions to incentivise entrepreneurship and tech adoption within a population. What comes next isn’t always easy to predict. The best you can hope for is that your startup ecosystem eventually gives birth to a startup culture.

And that’s where things get interesting.

AJVC: Origins

This, is the Indian startup ecosystem. It is also the start of a terrible analogy.

On the surface, you have the Order. These are the institutions and entities that represent the formal components of India’s startup machine. This is the Venture Capital and Private Equity funds. This is the accelerators, the incubators, and the bevy of professional services firms that help companies with their recruitment, compliance, accounting and tax requirements. This is also the various government bodies and ministries that legislate on industrial developments, the think-tanks that shape our tech policies, and finally, it is the startups themselves that round out this group.

Beneath the surface, you have the Chaos. This is the people, the networks and the conversations that provide the fuel to propel India’s startup machine forward.

It is the gossip that surrounds a major fundraise.

It is the banter during chai and sutta breaks between design sprints.

It is Indian startup Twitter, with all its gifs, memes and threads.

It is the fierce debates over ‘Zero to One’ and ‘The Hard Thing About Hard Things’.

It is the rush to fill a conference hall where Kunal Shah is generously doling out his latest epiphanies.

It is the journey from idea to rocket ship, where the real IPO is the friends you make along the way.

It is an energy that you can feel whether you’re in Bangalore, Gurgaon, Mumbai or Vizag. It is the belief in the art of enterprise, and the quixotic desire to shape your own future and that of your country. A philosophy that can be summarised within the maxim ‘to build is to be’.

It would be bold to try and bottle up this ‘Chaos’, and trickier still to channel it towards a single destination. However over the last three years a number of communities have emerged within the Indian startup ecosystem that are attempting to do just that. Some of them, like The Product Folks or Creators of Products are specifically aimed at cultivating and sharing knowledge and opportunities related to product management. Annual forums like Saasboomi and FTX are aimed at bringing together the best and brightest from Indian SaaS and fintech respectively. Companies like Devfolio and Airmeet are rallying the Indian tech community around virtual events and hackathons. However there is one community that has marked itself out as the premier on-ramp for people looking to teleport directly into India’s startup ecosystem. It helps insiders and outsiders to become part of the conversation, assisting all seekers to find the ideal landing spot for themselves.

A Junior VC was officially launched in 2018, though truthfully the AJVC story starts much earlier, when Aviral Bhatnagar (currently a Vice President at Venture Highway) was still in his second year as an undergraduate student at IIT Bombay. Growing up in the neighbouring city of Pune in Maharashtra, Aviral had been infused with a love of reading from a young age by his mother, who was happy to help nurse his infatuation with the English language in all its forms. A love of reading would become a love of writing, and writing would become the preferred medium of creative expression for a teenage Aviral. Like many ambitious Indian students that come from a middle class background, his passion would take a backseat in high school while he devoted all his free time to preparing for the notoriously bruising Joint Entrance Examination (JEE) in the hopes of snagging a golden ticket to one of India’s most prestigious engineering colleges. Aviral himself writes in an old blogpost that:

“95% of Indian households have a wealth of less than 10 lakhs. The average salary of an IITian in one year is equal to the entire household’s wealth. The exam gives families a shot to transform economics for a generation. It is an incredible machine that is a ticket to upward social mobility…The IITs are luxury goods in the field of education.”

After achieving safe passage through the JEE, Aviral, now fully embroiled in the rigmarole of IIT life, was looking for ways to reconnect with his cherished craft. He began experimenting with online blogging by creating Facebook groups (‘IIT-B Confessions’ and ‘Give up @ IITB’) where he would anonymously document the symbols and absurdities of daily life as a student at IIT Bombay. These Zuckerbergian shenanigans would earn him the adulation of his peers and the ire of his school administrators, and even make it to the back pages of the Hindustan Times.

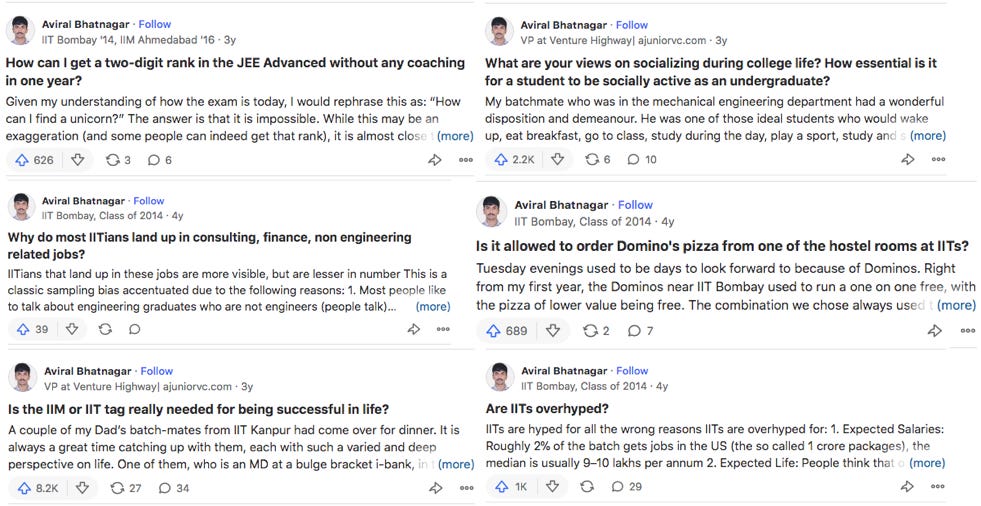

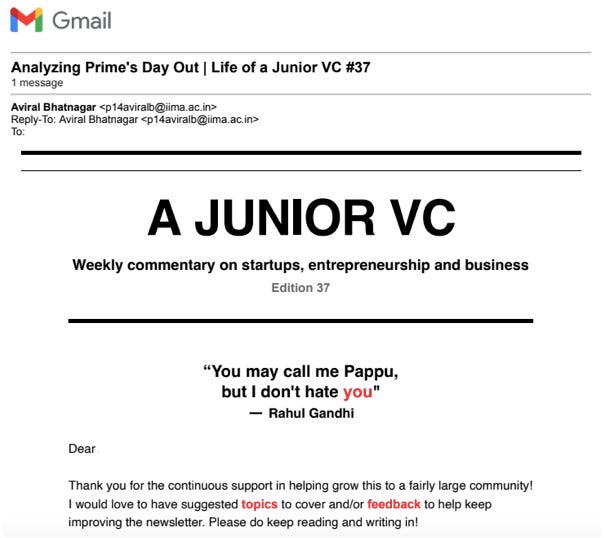

These early efforts at publishing gave him a taste of virality and an appreciation for the nuances of growth hacking online. His real breakthrough would come in 2012, when some of his college seniors pointed him towards a relatively new social media platform named Quora. Launched in 2009 by two former Facebook engineers, Quora was providing a way for people to ‘ask questions, get useful answers, and share what you know with the world’. It had garnered significant buzz for the simplicity of the user interface and the utility it offered as a more ‘personalised google search’. Aviral began to hone his writing ability by answering questions from users on Quora, ranging from the innocuous (“What’s the best superhero movie?”), the personal (“What motivates you to write online?”), the practical (“How does one choose their college major?”), and the philosophical (“Is the pursuit of wealth key to a happy life?”).

At his peak he was writing two or three answers every day on a wide range of topics, and started picking up followers that were drawn to the authenticity, relatability and eloquence of his responses. As he spent more and more time on Quora, Aviral noticed that there were a flood of questions coming from users who were curious about the subject of IITs - how to get in? how to prepare for the JEE? how was the lifestyle? did it really help your career prospects? etc. The curious part was that these questions were often being answered by non-IITians, which meant that the perspective being offered was often skewed.

He recounted how he “started writing initially because there were a lot of myths about the IITs. We are a small minority that gets a disproportionate amount of attention. A lot of it is good, some bad, and some plain ugly. Few of us are vocal, and I thought it might be good to be a small voice that tries to give a more detailed perspective about the IITs. The core I tried to drive to always was the fact that we are human, with our struggles and our doubts”. His fundamental issue was that out of the 0.3% of applicants that get into the IITs, few were outspoken, meaning that the 99.7% was often left with crafting the narrative on IITs and shaping the public image of IITians. That’s when the wheels began to turn.

Aviral began to focus his Quora activity specifically on questions relating to the IITs. Because of the mythology (good and bad) that surrounds IIT culture, he started seeing a more enthusiastic response to his writing. Parents and students were looking for any informational edge they could find. This was a high-intent topic, and there weren’t many voices offering an honest ‘insider’s perspective’ like he was. As his follower base crossed 15K on Quora, Aviral himself moved on to do a post-graduate MBA at the Indian Institute of Management (IIM) in Ahmedabad. The IIMs, like the IITs, are another bulwark of post-Independence Indian ambition. Established in the 1960s to meet the professional talent requirements of India’s public sector enterprises, the IIMs were also enshrined as ‘institutes of national importance’ via a piece of legislation passed in 2017.

Aviral could now call upon his own experience applying to and getting into two of India’s most celebrated educational institutes. He became a go-to source of IIT and IIM knowledge on Quora. Over the course of his two years as a post-graduate student, his audience grew from 15K to 60K. He had a front row seat to watch the magic of compounding play out in real time. By the time he graduated, practically every first year student in the batch below him had at some point relied on one of his Quora answers to navigate the admission process or just life in general at IIM. He had earned the goodwill of his peers by freeing up what had essentially been protected knowledge. But he couldn’t be a student forever, and there was more to life beyond the college experience.

Aviral’s two years at IIM (2014-16) coincided with the onset of India’s most recent phase of startup obsession. Aviral himself had already dipped his toes into the startup and investing world in the guise of an intern during his summer breaks as a student. For many ambitious Indian graduates ascending to the workforce in the 2010s, India’s startup landscape had become a viable (and in many cases, a preferred) option as a springboard to a successful career. Startups had begun to capture the mindshare of college campuses that had traditionally been the uncontested domain of blue-chip MNCs like Coke, Unilever or Goldman Sachs. In his last couple of months at IIM, Aviral secured a role at Guild Capital, an early-stage venture capital fund that was in the process of setting up shop in India. He would be just the firm’s third employee in its Indian office. Realising that there were other students like him looking to break into the world of emerging tech, Aviral once more expanded his repertoire on Quora to covering the in’s and out’s of India’s startup and venture capital ecosystem.

He began to weigh in on everything from Swiggy’s business model to Walmart’s acquisition of Flipkart to the legality of bitcoin in India. His own celebrity grew to the point where Indian users started addressing their general queries about tech and startups to him directly, prefacing their questions on Quora with ‘What does Aviral Bhatnagar think about…’ (eg: ‘What does Aviral Bhatnagar think about the gig economy in India?’). Aviral, on the other hand, was realising quickly that the life of a venture capitalist can often be lonely, especially at a small fund that had to scrape and claw its way to having any chance at winning the best deals. As his follower base inched closer to 100K, he began to see a return on the six-year investment he had made on the website.

“People that had been following my writing on Quora started reaching out to me saying they had launched a new venture. I used to get messages from ex-IIT and ex-IIM students thanking me for inspiring them to take the leap into the VC and startup world, asking if I would take a look at their companies. Quora had serendipitously become a source of deal flow. I realised that there was something special happening here”

Aviral experienced the strongest validation of this thesis in early 2016 when he received a Quora DM from Gaurav Munjal, who would go on to become one of the most celebrated founders in India. Gaurav was the CEO and co-founder of Unacademy, a leading online platform for educational content. Like Aviral, he was also a prolific writer on Quora, and had actually reached out to see if the young VC would be interested in coming on board as a teacher on Unacademy (“I appreciated the offer, but I asked him for a pitch deck instead”). Aside from this first attempt at cheeky opportunism, this would start a trend of potential investees finding him through his writing on Quora. The incident would also help him understand the immense power of media to make connections online.

It was around this time that Quora had started a ‘blogging’ feature on its website. Although writing had always just been a hobby, Aviral had seen firsthand that his passion could actually make a difference to his career too. If he could tap into his Quora distribution he might be able to give himself an edge as an venture capitalist. So he made the decision to start a separate blog on Quora where he would curate and publish a list of relevant startup literature (news, podcasts, essays etc) every week. The name of the blog?

After three months of toiling on the new project, Aviral decided that it was time to shift base. The quality of discourse on Quora had begun to dip. He was being peppered with the same questions over and over again. The platform itself wasn’t seeing the kind of engagement it had in the early 2010s. At the same time, newsletters were becoming cool again courtesy of tools like Ghost and Substack. In June 2018 he shared a simple Google form on Quora inviting his followers to sign up for a newsletter about startups and received a grand total of 45 responses. Thus, inspired by the blogs of legendary investors like Fred Wilson (Union Square Ventures) and Paul Graham (Y Combinator) Aviral made the decision to spin out the Quora blog into an email newsletter. In doing so, he also made a small cosmetic change to the presentation, a bit of minor surgery reminiscent of Mark Zuckerberg dropping the ‘the’ from ‘thefacebook’.

And so ‘A Junior VC’ was born.

AJVC: In Search of Scale

All the early traction for the newsletter came from word of mouth. The problem was that there was no real way to discover AJVC unless you were forwarded the original email. There was no website and no other online HQ - just a link to subscribe at the bottom of each edition of the newsletter. By this point the newsletter itself was beginning to evolve too. It had started out as a weekly collection of links with a sprinkle of commentary from Aviral. But on the back of reader feedback he began to focus more on the critical analysis of individual companies and less on curation. The length of each piece subsequently ballooned to the point where he could now publish only once every two weeks. Coupled with his day job and the fact that he was spending more of his time listening to pitches and attending board meetings, it was getting harder and harder to maintain quality. Aviral had laboured his way to 1000 newsletter subscribers but it was clear that in order to take the next step he would need some help.

So in June 2019, he called for back up.

Aviral received 170 responses to his request for help. After a brief assessment process, he selected Abhinav Ghosh, Keshav Bagri, Saloni Goel and Shiraz Kazmi to make up the AJVC Founding Team. The common thread running through each of the new additions was an appreciation of Aviral’s writing on Quora, a passion for startups, an ability to bring something new to the table, and the fact that they were all either:

- students looking for a way to engage with the Indian startup ecosystem, or

- recent graduates that had taken their first professional steps as investors, founders, engineers, operators, and product managers

It would mean that AJVC now had a template for adding more members, a cultural consistency with which to evaluate potential new joiners. The reinforced team created a modus operandi that would allow it to scale sustainably. Every two weeks they would collectively decide on a topic to focus on (typically a startup that had just raised a round of funding and/or was enjoying a moment in the spotlight). Aviral would work on the outline, Abhinav would work on design, and Keshav, Saloni and Shiraz would contribute the content for each piece. Aviral would conduct one final edit before hitting ‘send’ at 9:30 am every other Sunday. The goal was to prioritise quality over quantity, and to maintain a healthy email open rate (45-50%) even as the subscriber count increased. Above all, they committed to never missing an issue (and they never have).

“We will never compromise on consistency. I want people to know that it is 9:30 am on Sunday because they have an email from AJVC sitting in their inbox. We owe that to our readers. That’s why we can never miss.”

Along with the new editorial process, the team also became more intentional about growing the subscriber base. Aviral had experimented with the practice of posting snippets of the newsletter content to his LinkedIn feed every week. This opened the door to a new audience for AJVC. Each issue would spark an enthusiastic debate in the comment section and result in a flurry of requests from people asking how they could access the original content. LinkedIn proved to be the key that unlocked the gates of virality for AJVC (as opposed to Twitter, which is the conventional domain for trendy startup content). On the other hand, existing subscribers had been complaining for a long time that the newsletter was undiscoverable. So on 28 August 2019, the first AJVC website was launched, finally giving them a permanent home on the Internet.

Each LinkedIn screenshot would now be accompanied by a link to the website in the comments. The AJVC machine was kicking into high gear. Founders were noticing the credible work being done by this band of young enthusiasts. They began to receive praise for the depth of their research, their optimistic outlook, and their knack for covering companies that eventually turned into unicorns. Infra.Market, a $4.5bn online marketplace for construction materials, still sends out a link to the AJVC piece about them as a supplement with all their recruitment collateral, declaring it the closest canonical record of the Infra.Market story. Aviral was also seeing his own deal flow and access to founders improve as a result of the newsletter’s popularity. His bosses at Guild Capital were happy to encourage his passion project that seemed to be having a net positive effect on the fund as well.

Along the way, the AJVC value proposition began to crystallise.

“We saw a whitespace for conversations within the VC and startup ecosystem in India. The newer ‘subscription’ media had taken a journalistic approach to covering the space, often leading to a negative or crooked portrayal of Indian entrepreneurs. The legacy media is devoted to sensationalism, veering between cheerleading massive fundraises or harking impending doom on embattled companies that are trying to do their best. AJVC wants to provide a balanced view, but one that aims to encourage and support the efforts of Indian founders that are attempting to achieve audacious goals”.

By the end of the year, the newsletter had crossed 5000 subscribers. It was time to test the limits of product-market fit. In December 2019 Mazin Biviji, a longtime AJVC reader who was then based in Paris, reached to Aviral to ask for advice on a new startup idea he had. During the conversation he suggested that AJVC should experiment with different storytelling formats, and proposed the idea of a new podcast. Aviral was impressed, and invited Mazin to join the team to spearhead AJVC’s first product expansion.

The podcast was a runaway success. Similar to the newsletter, it is published twice a month on alternate Sundays at 9:30 pm. The podcast opened the door to an audience that preferred getting their startup content in audiovisual format. It deepened the engagement with existing subscribers. The interview arrangement allowed founders to shape their own narratives and share a first-hand perspective on their journeys. As a testament to the credibility of AJVC’s distribution, the guest lineup for the podcast is currently booked out for the next six months, with many founders choosing to announce their fundraises on the AJVC platform. The successful launch of the podcast would solidify another core tenet of the AJVC story - that ideas for new products typically come from members of the community itself, who are then invited to come on board and use the AJVC platform as a playground for their creative expression.

The AJVC train was now surging forward courtesy of the twin engines of newsletter and podcast. At the same time, the onset of the pandemic had also accelerated the consumption of content online. By the summer of 2020, their subscriber base had reached a critical mass. The founding team sent out another SOS for support, once again relying on their own audience to scale the team. This time they received over 750 applicants who wanted to contribute to the AJVC cause. The next milestone would be a true litmus test of the strength of the AJVC community. It would prove whether their mission to ‘democratise conversations around startups in India’ would succeed or fail.

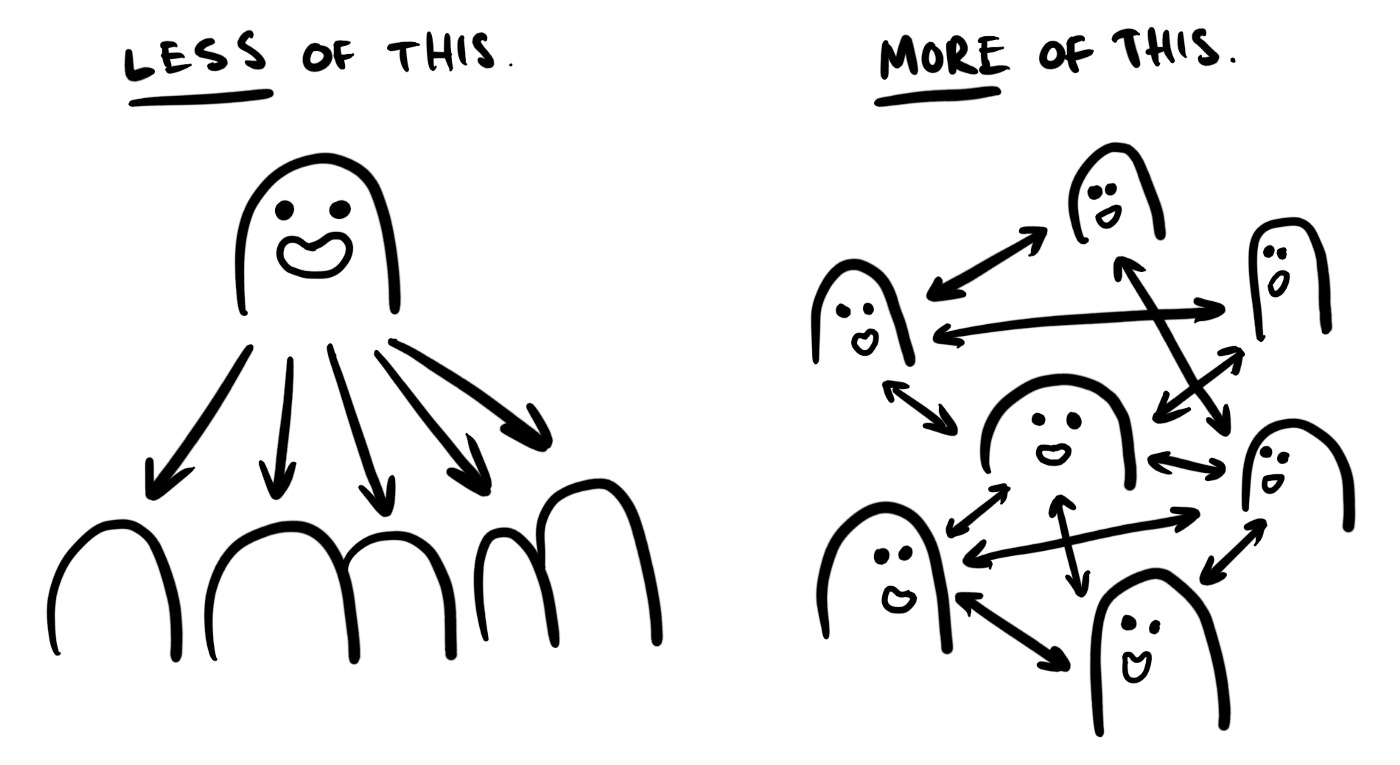

In May 2020 the team decided to turn a mirror onto its buzzy audience via a newly launched AJVC Slack channel. Longtime readers and listeners had repeatedly requested for a way to interact with other members of the community. So far the communication had always been top-down. Aviral and his team would create, and the audience would consume. The Slack channel was a way to redirect the flow of conversation, allowing for a richer and multi-layered user experience. It became a way for founders to find their next hire, their next co-founder, their next customer, or even their next investor. It offered an opportunity for students and graduates to brush shoulders with their startup heroes. At its most basic level it gave people an outlet to bond over their love of tech and startups. Mitali Agarwal and Raj Datta from the AJVC team helped to periodically stir the pot, hosting AMAs (Ask Me Anything) with founders and VCs every Sunday night, and facilitating 1-on-1 ‘coffee chats’ between members of the community.

AJVC wasn’t just a community anymore, it was a network. To illustrate, in April 2020 the AJVC team organised a ‘Covid Sandbox’ where people that had been laid off from their jobs could connect with recruiters via the AJVC website to find their next roles. Over 20 people received full time job offers. The strength of the community had been demonstrated in the most dire of circumstances. The first 200 signups to the Slack channel had come via a Google form posted on the website (“a google form is an underrated way to test your product MVP,” says Aviral). Access had initially been restricted to subscribers of the newsletter. Once it was opened up to the wider public it would grow to 5000 members by the end of the year, and currently stands at almost double that amount. The team tracks the metrics of the Slack channel with the same vigour you would expect from a leading social media company. There are 1000-1500 Weekly Active Users (WAU) which represents 12-15% of the overall base. 40-50% of participants make an appearance once a month. And crucially, 90% of the conversation takes place in private chats, meaning that the AJVC audience is using the Slack channel in the same way they would any other social platform - to make new connections, to interact with familiar faces, and to get things done.

Now with three products under its banner, AJVC was entering its next phase of evolution. The crucial change here was the increasing prominence of the AJVC brand vs the individual profile of any single member. The original newsletter had been a direct descendent of Aviral’s celebrity on Quora. But as the roster of products expanded and new subscribers trickled in from different corners of the Internet, it was important that the AJVC brand could stand on its own feet regardless of who was pulling the strings. This was done by creating a defined structure and publishing process. Each member was given the autonomy to conceptualise and test new products as long as it was in service of the overall objective - to build an oasis for the startup obsessed. That’s what helped AJVC become the premier passion project for people working in Indian tech. Nobody gets paid to contribute their time or effort. Team members are happy to play a part in building something greater than themselves. The next product launch would exemplify this shared philosophy.

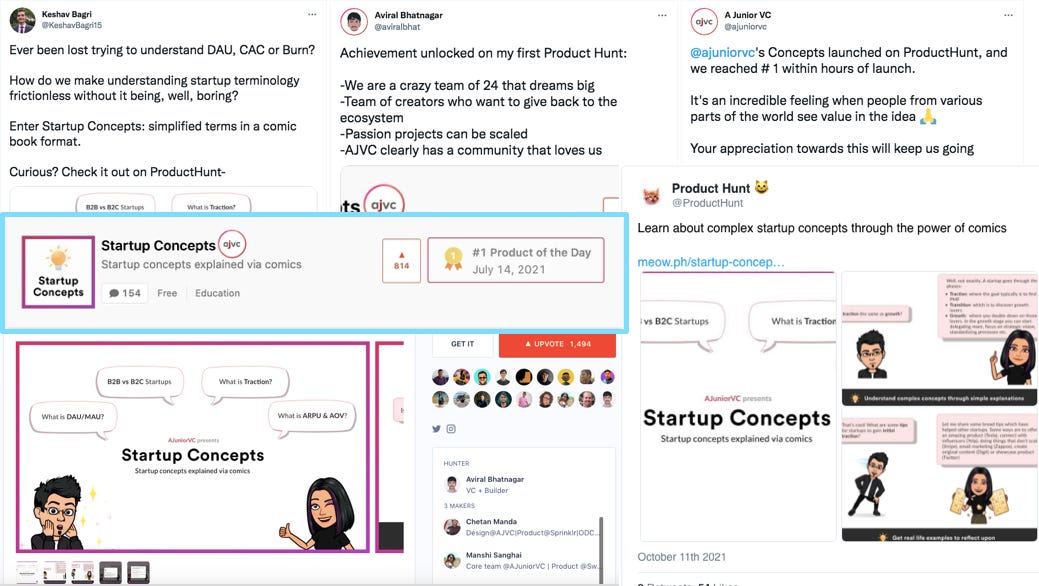

As the team continued to pump out its newsletter and podcast, Keshav Bagri (from the AJVC Founding Team) noticed something interesting happening in the comment section under each piece of content. Readers/listeners were showing up with the same technical queries week after week. “What is PMF?” “What is CAC?” “What are unit economics?” He realised that much of the jargon used in everyday tech parlance was going over the heads of their audience. That’s because a decent chunk of the AJVC community comprised of students, recent graduates, and young professionals looking to break into the startup world. Keshav saw an opportunity to make life easier for this group.

In July 2020 the AJVC team would launch ‘Startup Concepts’, a product that offered a slick way to bridge the information gap for tech newbies. It would quickly become one of AJVC’s most cherished offerings, ticking off a number of boxes at the same time. First, it helped make the nuances of the startup world more accessible to a wider audience. And second, it meant that AJVC content creators wouldn’t have to waste time and space explaining the same terms over and over again in every newsletter or podcast. They could just provide a link to the ‘Concepts’ page for that subject. The friendly presentation of the material and the visual flair contributed by AJVC designer Chetan Manda proved to be a match-winning combination. 12 months (and 30 editions) later they launched Startup Concepts on Product Hunt. After a manic 24 hours where the entire AJVC community mobilised in support, they would achieve the holy grail of ‘#1 Product of the Day’, the highest flex for anyone building anything cool on the Internet today. They would hold on to the top spot for the rest of the week.

The success of Concepts would help AJVC close out 2020 having racked up some impressive numbers:

1.2 million hits across all platforms

A roster of 5 products that included the newsletter, podcast, Startup Concepts, the Slack channel, and AMAs

20K+ newsletter subscribers

100K+ monthly website visitors

A Top 10 podcast in the Indian tech category

5K+ members in the AJVC Slack channel

A Net Promoter Score of 65+

To fans and outside observers, it has been impressive to watch this team continue to test, ship, and refine new products at such a furious pace. The seeds of compounding have begun to bear fruit. The virtues of process and structure have helped to construct a well-oiled machine. The formula has been tried and tested. AJVC spent much of 2021 continuing where it left off.

They’ve now crossed 40K newsletter subscribers and over 120K monthly visitors. They added new products like McMarkets (sector-wise analysis) and Startup Stats (infographics and data visualisation) for India, along with an additional vertical for newsletter stories based on the startup ecosystem in Southeast Asia.

They continue to lead the way as the principal side-hustle of choice for India’s startup obsessed. For every new product that demands a new skillset, they’ve added new members to fill specific roles (eg: video producer, social media manager etc). The AJVC team now stands at 25 people, all of whom volunteer their extra hours between full-time gigs at startups, investment banks, MBAs, VC funds, and everything in between. They even started an AJVC Fellowship programme for college students to do a three-month tour of duty with AJVC to prove why they should be a permanent part of the team.

AJVC is now an omnipresent fixture in India’s tech landscape. They’ve officially inserted themselves into India’s startup story. What began as a passion project now boasts an output and an audience (and certainly a fandom) that would rival that of any other tech-focused media entity in the country. With regards to their future roadmap, they’ve earned the luxury of being able to choose their next adventure. Its taken years of consistent toiling to get to this point. However, the thing about putting your head down and building, is that when you do eventually look up to smell the roses, you might not even realise what you’ve built.

AJVC: A Metamedia Brand

In the last six weeks I’ve had dozens of conversations with AJVC team members, Indian startup founders, VCs, and members of the AJVC community, with the specific purpose of asking them one simple question - What is AJVC?

The colourful range of responses I received is what makes the AJVC story worth telling. I heard that AJVC was:

“A social network built around a clearly defined context”

“A newsroom for startup content”

“An index for the Indian startup ecosystem”

“A community of like-minded people that have an appreciation for entrepreneurship”

“A professional network masquerading as a social network”

“A platform for conceptualising and distributing startup-focused products”

“A cross between a job portal, a talent agency and an MBA”

And most interestingly, that AJVC was “a startup waiting for the right business model”.

Herein lies the rub. The brand has come to represent different things to different people. That’s why their journey (and their process) warrants closer examination. Their success validates a number of technological trends that are shaping the current iteration of our socioeconomic zeitgeist (eg: the creator economy, community-led growth, distributed/remote teams etc). At the moment it is difficult to pin them down to an exact organisational definition. That’s mainly because we haven’t had the commercial vocabulary to describe the entities that do what AJVC does without generating some form of advertising or subscription based revenue.

We’ve historically legitimised groups of people coordinating resources and producing value over the Internet only through the prism of incorporation. Our mental models are limited by convention i.e. a group of people come together to build a company → the company creates value by producing a product/service → either customers pay to use product/service or advertisers pay to subsidise the price of product/service in exchange for the attention of end users. The incentives and rewards for each party are well understood. Its why the busiest neighbourhoods in the ancient metropolis of the Internet tend to have rigid two-way streets for generating and exchanging value.

But the old world is rapidly becoming the new world. We are on the cusp of a transition from the second era of the Internet (Web2) to the third (Web3). The most significant change here is the shifting balance of power from the administrators of centralised platforms to the actual builders and users of Internet products. Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you’ve probably seen your timeline being invaded with news about Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs), Decentralised Autonomous Organisations (DAOs) and Decentralised Finance (DeFi). This is no accident and no passing trend. Twelve years after the birth of bitcoin, the whimsical world of cryptocurrencies and blockchain technology is ready to take centre stage in the reimagining of the Internet.

Crypto has gifted us with innovative ways of creating and transmitting value online. It is the catalyst the triggers the alchemy of social capital to financial capital. At scale. In other words, crypto will unlock new business models for Internet creators and celebrities in every field (eg: writers, illustrators, streamers, teachers, musicians etc). This collision of crypto and creators is already leading to the blossoming of a new species of brands that look very similar to AJVC i.e. shapeshifting Internet blobs that do a bit of everything.

These Web3 media brands, or ‘Metamedia’ brands, are ‘planets in the solar system of the internet that are teeming with creative life, with their own independent micro-economies built around an orbit of different products, and a content-driven gravity that sucks in attention from all corners of their galaxy’.

If that doesn’t make any sense, don’t worry. In the paragraphs below, we’ll take a look at the AJVC story through the lens of Web3, and particularly the three-step calculus involved in the creation of a successful Metamedia brand:

Content

Community

Crypto

1. Content

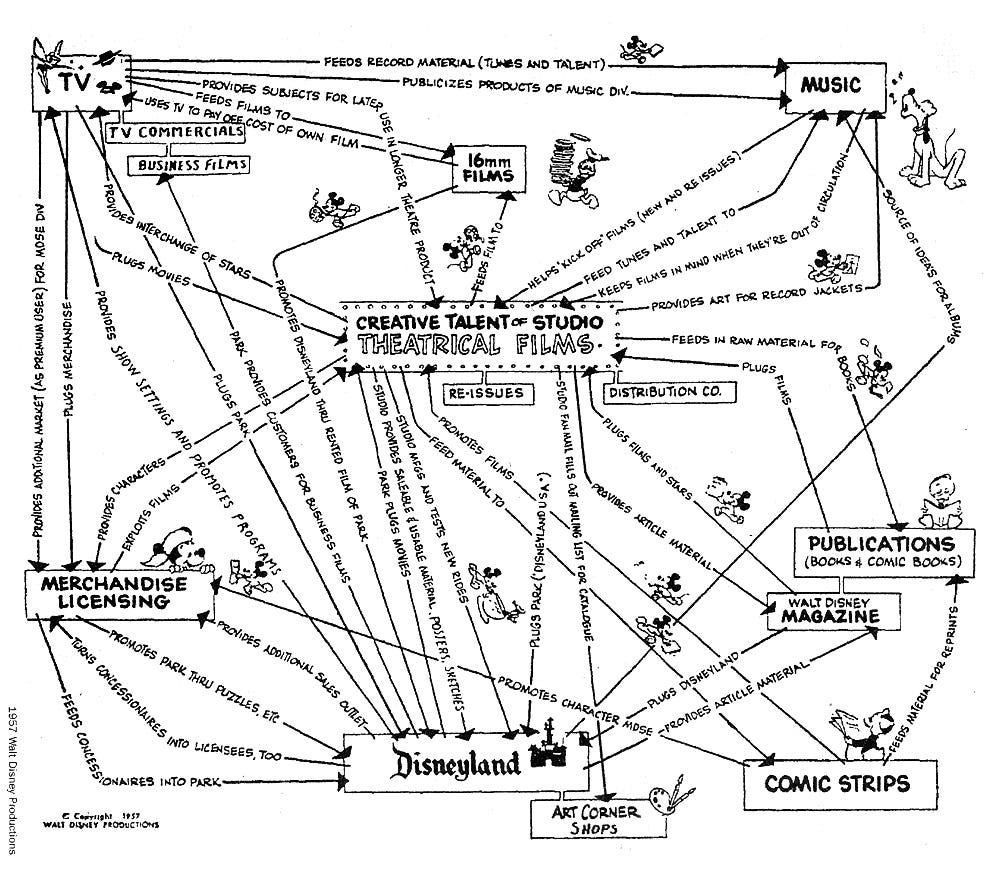

In 1957, Walt Disney would scribble down the now iconic vision for his 35-year old company, whose incredible success so far had owed much to the popularity of a certain cartoon mouse. His blueprint featured a ‘Synergy Map’ of different businesses and services that each reinforced and complimented each other to create a harmonious product flywheel that was in service of the overall Disney brand. For example, Disney animators would create cartoon characters that would be featured in television shows and movies produced by Disney Studios. The proliferation of these characters on TV and in cinemas would turn them into overnight brands in their own right. The success of Disney media would spark the desire to buy Disney merchandise, which would be sold at Disney-themed amusement parks. Disney parks and toys gave parents and kids a way to exercise their fandom and increase the likelihood that they would continue to consume Disney content. This ouroboric approach meant that there were infinite ways for Disney to engage with its audience and several markets in which they could conduct their commercial magic. Walt Disney proved to be far ahead of his time when it comes to understanding how the interplay of content and commerce can create a virtuous cycle for media operators.

More than half a century later the Disney flywheel still provides a useful framework for anyone looking to create a successful consumer brand around their content or construct a commercial ecosystem around unique intellectual property. It is particularly instructive for individuals looking to build businesses around their creative output.

We are currently in the midst of a labour revolution that has entered our cultural consciousness under the guise of a more innocuous name - ‘the creator economy’. Platforms like Substack, Anchor, Teachable, Twitch, Youtube etc are providing individuals around the world with the software tools they need to convert their talents (writing, podcasting, teaching, dancing, gaming etc) into full-time businesses. These tools are giving creators a way to build and monetise their audiences either directly (subscriptions, tips) or indirectly (consulting, brand sponsorships, angel investing). Creators that manage to attract significant eyeballs can effectively become distribution channels for a broad range of product and services that resonate best with their individual audiences.

The most successful creators are exploiting a poorly hidden secret of the Internet today, that every company is a media company. Or to be more precise, any entity producing content with a unique voice is a media company. This includes users on Twitter, podcasters on Spotify, streamers on Youtube and certainly bloggers and newsletter writers employing a number of different tools. Once the Internet reduced the cost of creating and distributing content down to zero, it meant that every person, group or organisation online was competing with every other person, group and organisation for the attention of users. On social media, we’re all founders of our own media companies. We are brands waiting to be built. We are celebrities waiting for the paparazzi to appear.

Big budgets, elaborate productions and legacy infrastructure are no longer pre-requisites to building competitive media brands. The entities that dominate the media landscape of the future will be individual-led, personality-driven, and will prioritise authenticity over professional pedigree. The content will speak for itself.

AJVC is a product of the creator economy. An operation that started as a series of curated links on Quora has evolved into a recognisable Indian media brand today.

Similar to Walt Disney’s Synergy Map, Aviral also talks about the logic that infuses each of the puzzle pieces that make up AJVC’s product catalogue today:

“We have an internal hierarchy of products that helps us meet the needs of our community and also helps to segment our user base. The lowest intent users find our content via their social media feeds. It takes the least amount of effort and has the widest distribution. Users that are curious to know more will then navigate to our website. If they like what they see they’ll sign up for the newsletter which means they’ve invited AJVC to be a part of their lives. The newsletter will redirect them to all our other content products, where they can engage with the brand in their preferred medium (text, audio, graphics etc). If we’ve added value to their lives, these users will eventually join our Slack channel. The level of commitment increases as they transition from newsfeed observers to contributing members of the AJVC community. Each of our product tries to meet their needs in a different way. We want to give them a reason to stick around”

The AJVC team is wary of switching on the ‘monetise’ button just yet. There’s a case to be made that a profit-motive would compromise the integrity of their startup coverage. It would also pose tricky questions about how to allocate funds, and also the status and compensation of team members, all of whom are currently motivated only by their passion and curiosity. The pressures of making money would sully the purity of the endeavour. However with over 40K newsletter subscribers and over 120K website visitors every month, AJVC might not have a business model, but they do have a captive audience, and that’s enough for now.

The pristine soil of Web3 will present fertile ground for the proliferation of ‘Audience-first’ companies. Online writer David Perell says that for the digital economy, ‘Audience first’ will be a ‘new way to test the feasibility of a business idea’. This upside-down method of company building has a number of benefits. Instead of building a product and then generating demand for it, you can now publish quality content that builds you a loyal audience, and then let your audience tell you what products it needs. You get rapid feedback on your ideas from people whose trust you’ve already earned. It is a much safer way to embark on a commercial enterprise because you already know that there’s a market for your product. They’ve told you themselves.

Given AJVC already has a captive audience that comprises of founders, operators, investors, professionals and students interested in technology and startups, they could eventually:

1. bring in advertisers to sponsor each issue of the podcast and newsletter. Morning Brew, which is a free daily newsletter that covers business and tech news for a younger audience in the US, was similarly started as a university passion project by Austin Rief and Alex Lieberman. Because of the love of their readers and their hold over a millennial audience, they managed to pull in $20 million in revenue from advertisers in 2020, and eventually sold to Business Insider for $75 million.

2. build a software offering aimed at their target market. For example, their audience could be on the lookout for a cap table management solution, or payroll management app, or note taking tool. The AJVC audience is already open to trying different content products created by the team. It wouldn’t be a stretch to change the definition of the ‘product’ and still be reasonably certain that their users will give it a fair shot.

3. launch an online course for professionals looking to enter the startup world. The future of education is cohort-based, community-driven and experience-led. Cohort based courses focused on a particular niche (eg: tech skills) are poised to disrupt the legacy education system. The creator economy has helped to invalidate the rigid system of credentialing that only recognises what you can fit on your LinkedIn profile. Startups like OnDeck and Stoa School have drawn significant attention and funding to support their fresh approach to an online learning model where the curriculum is designed and delivered by the best in their field. For AJVC, an online course would just be a repackaging and reorganising of the content they already deliver today in a different format.

4. start a VC fund or syndicate that invests in the companies and trends they write about. Founders are happy to have them on their cap tables because AJVC can offer them a channel of distribution via their newsletter audience (and can also help to tell their stories). The AJVC ‘brand’ already has the trust of thousands of current and future startup founders in India. Why wouldn’t they be able to compete with more established names? Packy McCormick (Not Boring) and Harry Stebbings (20VC) are recent examples of how content creators can leverage a successful newsletter/podcast into a successful investing career. In a world where capital is a commodity, founders are looking for investors that can add value in different ways.

There are no shortage of options if the AJVC team decides to go the commercial route. In any case, they might not have money in the bank yet, but they do have something that may prove more valuable in the long run.

2. Community

"People may go to the library looking mainly for information, but they find each other there."

- Robert D. Putnam (Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community)

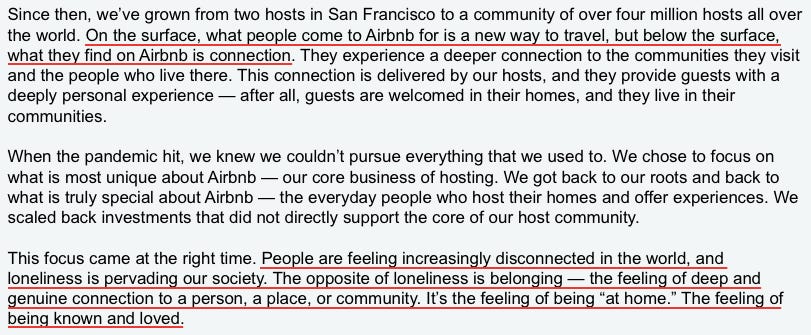

Airbnb went public on 9th December 2020. The startup that had disrupted the hotel and travel industry over the course of a decade finally marked its arrival as one of the biggest success stories of the gig economy era of consumer technology. In the prospectus document they submitted in the lead up to the IPO, Airbnb mentioned one particular word 166 times - ‘community’. They made it clear that they see their community of hosts and guests as a key strategic asset to fend off competitors. In fact, they consider themselves less of a business and more of a “community based on connection and belonging”.

They were correct about two things.

First, that people today really do yearn for ways to foster more intimate social connection. The curse of modernity is a disconnectedness that manifests in feelings of loneliness or a lack of belonging. The pandemic has certainly not helped this cause. One of the tragedies of our times is that social media and city living have improved social ‘access’, but have also left people feeling more isolated than ever. In large part that’s due to the receding of local recreation and neighbourhood activities (religion, malls, arcades, cinemas, physical sports etc) in exchange for the glitz and glamour of the instant-access Internet-enabled world stage that’s customised to each of our individual preferences.

“Once upon a time people were born into communities and had to find their individuality. Today people are born individuals and have to find their communities.”

- Youth Mode: A Report on Freedom

Its why shared experiences (like the World Cup final or the Game of Thrones finale) are so important. Our lives are made infinitely richer by the social ties that bind us. The Beatles were on to something when they wrote that we "get by with a little help from our friends." Today the corridors of social media are often too noisy to have meaningful conversations. Greg Isenberg, the CEO of Late Checkout, articulates this conundrum, commenting that “If you give everyone a microphone, it gets pretty loud. And its gotten really, really loud…the destiny of every massive social network or marketplace is unbundling. Its not a matter of if but when”.

The last generation of social media was built in a time where scale reigned supreme. More people, more conversations, more engagement, more clicks. The platforms themselves were generalised (Facebook, Twitter etc) to attract users en masse. But Web3 is swinging the pendulum the other way. Now we’re looking for fewer but more meaningful relationships online. Quality not quantity. We’re looking for context and commonality to drive connection with other people. That’s why the best conversations aren’t happening on newsfeeds anymore, they’re happening in private whatsapp groups, slack channels, discord servers and subreddits. People are retreating from the crowd in order to find their tribes.

Which bring us back to Airbnb. The second thing they correctly identified was the growing importance of investing in community-led growth. Community-building will be one of the defining pre-requisites of corporate success over the next 5-10 years. It is the reason why companies like Nike and Peloton will endure - they allow people to feel like they’re part of a larger movement, a shared identity built around a love of fitness and a commitment to better yourself. Their brands stand for something beyond what any single product or service could provide. Their customers feel comfortable tying their identities to what these brands stand for. It is a similar religious fervour that arises from activities like supporting a football team, working out at your local CrossFit box, contributing to a public GitHub project, or following Taylor Swift from country to country on her world tour.

“Building a community is everything to every company everywhere. I don’t care what company you are or what you sell. If your customers don’t feel like a community you’re going to suffer at some level”

- Mark Cuban🦈

According to FirstRound's State of Startups 2019 report which surveyed over 3600 startup founders in the United States - ‘Community is the new moat.’ The State of Indian Community Management 2021 Report declared that ‘Community is the new oxygen for organizations’. Building a community around a brand gives a company an unfair edge over its competitors. It converts your market into fans, meaning that you can take multiple shots on goal because you don’t have to spend anything to acquire customers. It means that your company can handle the odd bout of bad press because you know that your users are in it for the long haul. With technology trending towards commoditisation, the only thing you won’t be able to fake is your community.

AJVC managed to nail the delicate transition from audience to community. What’s the difference? Well, it comes down to which way the chairs are facing.

AJVC are aided by the fact that their content helps to set the context for their community. Everyone knows exactly why they’re here, and each new piece of content provides a new campfire for their people to gather around. VC Hunter Walk writes that “I’m of the belief that ‘Come for the Content, Stay for the Community’ will be one of the dominating themes for media this decade. As more creators break away from companies to go subscription indie, they’ll find it to be an effective and rewarding strategy to think of ways to build ‘whole is greater than the sum of its parts’ experiences”.

Every AJVC product is a conversation starter. The AJVC mission itself (‘democratising startup conversations’) is like a radio signal for other like-minded individuals to join. People resonate with the values of the brand, and the value they get from being part of the group. Having a Slack channel alone is not enough to prove that you have a loyal community, but if members in that Slack channel are spending time getting to know each other in private messages, and offering to help one another (with investments, hiring, expertise etc), then you might have something on your hands. Other signs that this thing is for real:

- the entire AJVC team mentions their association with AJVC in their Twitter bios

- the support of the AJVC community helped to get Startup Concepts to #1 on Product Hunt

- members of the community have started to create and share content around business-building in the AJVC Slack channel

- longtime fans of AJVC have started companies and changed career paths after being inspired by stories of Indian founders

AJVC has successfully transitioned from solo creator to independent media brand to thriving community. They are traversing a familiar path taken by brands like The Better India or Little Black Book (LBB) that managed to effectively straddle the line between content and commerce. They certainly have a number of options should they choose to create a commercial product that satisfies some need of their audience. However, as the Internet undergoes its own upgrade to Web3, the best Internet communities are no longer destined to end up as companies. No, they will be something else entirely.

3. Crypto

At various points over the course of 2021, we’ve been given a sneak peek into the future of the Internet. These trailers have trickled into our lives via headlines that announce the latest celebrity NFT collection, the latest bitcoin price surge, the latest company entering the metaverse, or the latest crypto project aiming to coordinate groups of strangers around the world towards an audacious goal like building a village or buying the US Constitution. We haven’t fully entered the matrix yet, but we’re getting close.

Crypto-economic experiments like Bitcoin, Ethereum, and others are edging towards maturity. They’re providing real-time proof of the potential of blockchain technology to change the way we transfer value over the Internet, and the various socioeconomic implications of this new paradigm. Blockchains are a novel way for people to organise and coordinate resources. Corporations are no longer the only viable form factor for orchestrating commercial activity online. Contracts embedded in code (‘smart contracts’) can dictate the actions of individuals through the use of cleverly designed incentives that enable disparate groups of people to mobilise around a collective mission.

If the Internet helped to convert communities into networks, then blockchains will help networks become markets. Value will flow freely through these networks in the form of a new economic primitive - ‘tokens’ - which can represent digital money, digital art, digital identity, digital IOUs, digital ownership or even digital voting rights. Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs) can be used to record the authenticity and ownership of unique pieces of media, unlocking an entire ecosystem of use cases around the creation and consumption of digital assets (like songs, images, gifs, essays, video game items etc).

The underlying philosophy of Web3 is decentralisation. The next iteration of the Internet promises to swing the pendulum of power away from central intermediaries and out to the edges i.e. to the creators and users of Internet platforms and products.

“Instead of placing our trust in corporations, we can place our trust in community-owned and -operated software, transforming the internet’s governing principle from “don’t be evil” back to “can’t be evil.”

– Chris Dixon (General Partner, a16z)

Web3 is about autonomy and ownership. In particular, creators will be able to directly monetise their work via their audiences, who will in turn have a stake in the financial upside of their patronage via the purchase of NFTs and other crypto tokens. For example, if Walt Disney had decided to sell a limited set of NFTs representing his most famous characters in order to finance a future Disney movie, his fans would enjoy the benefit of seeing their NFTs increase in value as Mickey Mouse became more and more popular with the general public, further strengthening their affinity with the brand. In other words, NFTs help to convert social capital into financial capital. Web3 is a transition from a time of likes, comments and subscribers to a time of creators, owners and tokens.