A Sonic Bridge to India’s Heartlands: The Story of KukuFM

How KukuFM discovered the elusive blueprint to building a business while 'Building for Bharat'

Hey folks👋

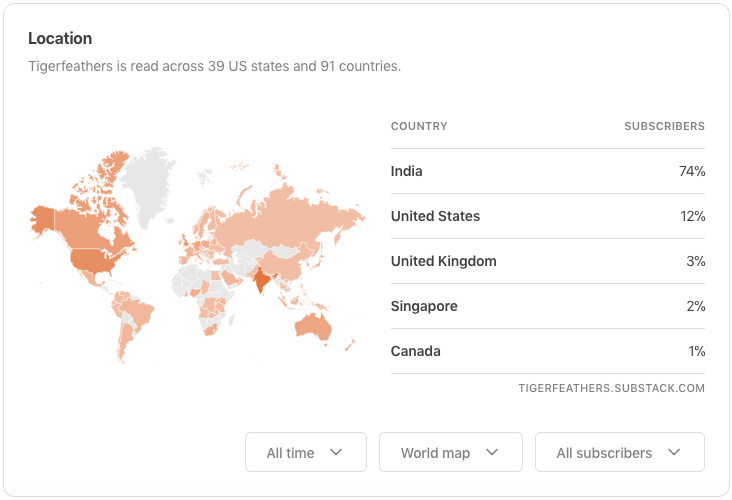

Welcome to the 504 new Tigerfeathers subscribers who’ve joined since our last piece.

If you’re a first-time reader of this newsletter and you don’t see yourself on this map, let us know. We’re getting matching tattoos of the flags of the next 9 countries to sign up👇

This edition of Tigerfeathers is brought to you by…Replit

Replit is an online platform that allows you to build software collaboratively with the power of AI, on any device, without spending a second on setup. They launched in India earlier this year with a mission to 'bring the next billion coders online'. With Replit, you can build, test and deploy any app or program directly from your browser or mobile.

Have an idea or side-hustle that you want to build but lack the skills or time to code it? Replit’s Bounties programme connects you with developers to help turn your ideas into full-fledged prototypes and products. Click the ‘Services’ tab and mention ‘Tigerfeathers’ while checking out to get 12,000 Cycles ($120 USD) in credits for any AI Service order.

If you’re interested in partnering with us on a future edition of Tigerfeathers, get in touch on Twitter (or by replying to this email).

At a company town hall earlier this year, the three co-founders of KukuFM were lobbed a question by Kunj Sanghvi, the company’s Head of Content. They were each asked to reflect on their five-year journey and pick their most memorable day at the office since launching the company in June 2018. The question was part of an in-house interview with the founders (conducted entirely in Hindi) to document the story of KukuFM for the company’s Youtube channel.

The founding trio - Lal Chand Bisu, Vinod Kumar Meena, and Vikas Goyal - had stitched together a colourful professional highlight reel over the preceding half-decade. This, their second entrepreneurial venture, had been seeded with the goal to build India’s first indigenous podcasting app. Several iterations and experiments later, that vision had morphed into something a little different. Five years after starting up, KukuFM had become the premier destination for vernacular audio content in India (i.e. content in local or regional Indian languages).

This wasn’t just some hollow title either. By the end of 2022, when accounting for paid subscribers, they were the largest platform for audio content in India - period.

For context, they had more paying subscribers in India than homegrown music-streaming platforms like JioSaavn and Gaana; more even than global audio giants like Spotify and Audible put together. They had managed to corral a larger recurring customer base than any other vernacular content platform in the country, many of which could boast gaudy user numbers in the hundreds of millions but were still struggling to nail down a sustainable business model.

KukuFM, though, had seemingly unearthed a proposition compelling enough to convince notoriously value-conscious Indian consumers to pay for content.

A little over two years since launching their paid subscription model, almost three million users had signed up to access their library of ‘non-music audio content’ - consisting of 150,000 hours of audiobooks, stories, courses, book summaries, podcasts, and original series (both fiction and non-fiction) across a variety of genres. It was an achievement made all the more remarkable considering their target consumer base fell within a demographic that is colloquially referred to as ‘Bharat’ (the Sanskrit name for India).

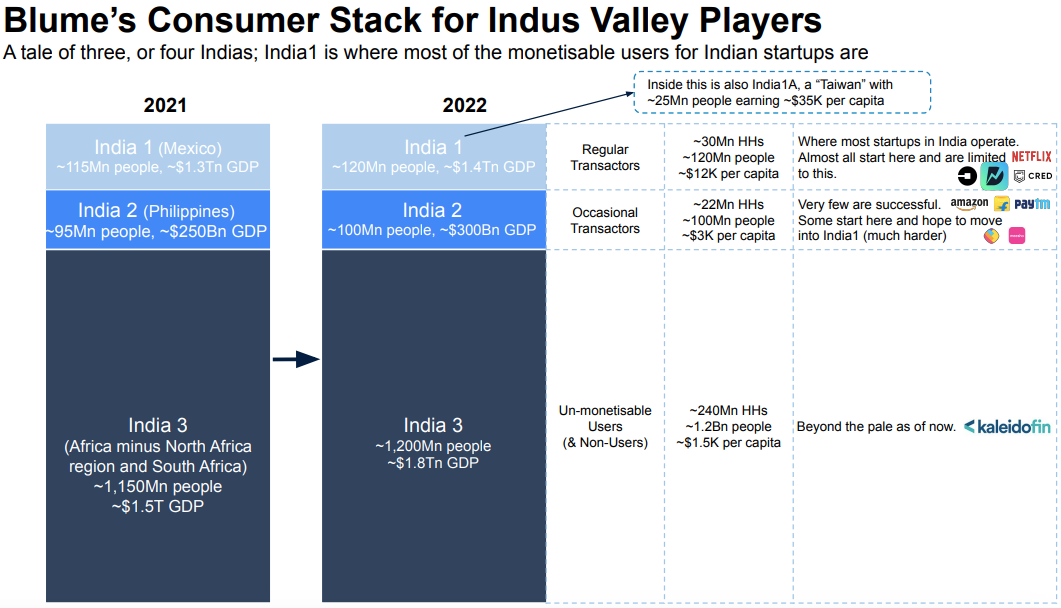

For the uninitiated, Bharat is not the nation of Apple stores, luxury malls, Broadway plays, fine dining, electric vehicles, cappuccinos, private schools, wellness retreats and destination weddings that the rest of the world commonly associates with the Indian growth story. No, Bharat is the prodigious segment of India (and Indians) that is a few steps further back in its economic trajectory.

This is the India of bicycles, farms, and government schools. It includes the estimated 1.3+ billion Indians that don’t speak English, and the 25% of Indian adults that lack access to a formal education. It is blue-collar India and small-town India, where per capita incomes typically range from $500-$2000 per year.

Needless to say, Bharat has a different set of capabilities and priorities with regards to discretionary spending when compared with India. This is a cohort that is yet to join the country’s nascent consuming class in earnest. Here, purchase decisions are mostly confined within the maxim of roti-kapda-makaan (food-clothing-shelter). Items that make it onto a monthly budget are usually those that have cleared a stringent threshold of value and necessity.

And yet, millions of people from within this segment have deemed a KukuFM subscription worthy of inclusion in their routine expenses. In an era where data prices in India are among the cheapest in the world, where endless oceans of content swell in every corner of the Internet, where you can spend your entire day being entertained and informed online for free, Indian consumers are volunteering Rs. 899 (~$11) of their hard-earned and hard-spent money for an annual subscription to KukuFM.

Why?

Well, in a nutshell, that question is why I wanted to tell the KukuFM story…

…and to answer it, we have to revisit the interview from the start of this piece.

“Guys, 2.5 million subscribers, available in seven languages, a team of 200 people…in the last 5-6 years, which has been your favourite day at KukuFM? What’s been the most memorable day at KukuFM?”

- Kunj Sanghvi (Head of Content, KukuFM)

Reflecting on the question from Kunj, each of the co-founders (all of whom hail from tiny villages in North India) offered thoughtful responses that illustrate why their story is so compelling, and why I was keen to tell it.

The company’s CTO, Vikas Goyal, said that, for him, it was when the first user on KukuFM signed up for a paid subscription plan.

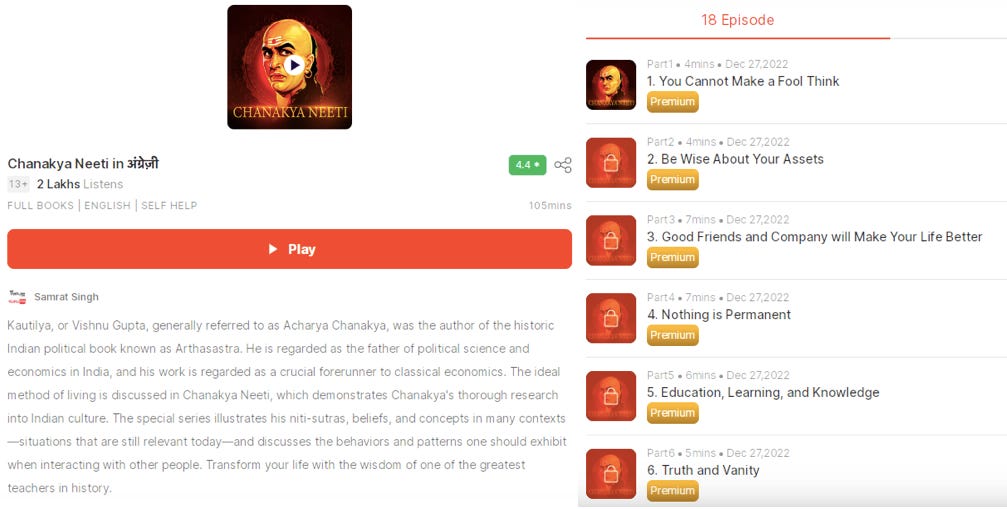

He recounted how, when that first transaction went through, it was an instant validation of their efforts because it meant the team had created something worth paying for. Incidentally, KukuFM’s first subscriber was a grain merchant from Rajasthan who enjoyed listening to their audio series on Chanakya, the ancient Indian polymath and royal advisor to emperor Chandragupta Maurya. He later revealed to the team that he would use the lessons from the programme to inform his daily business decisions.

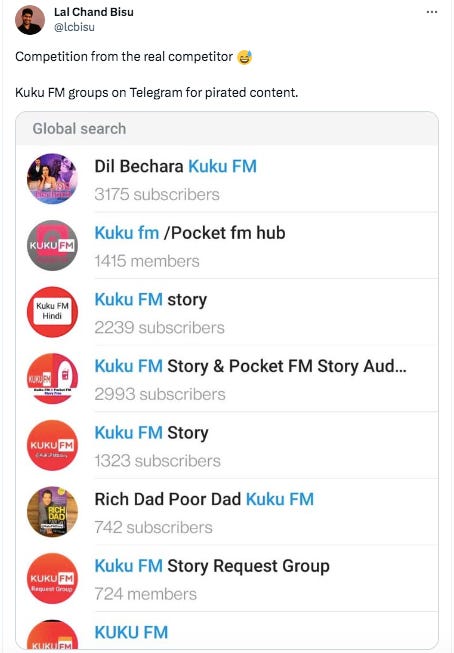

KukuFM’s CEO, Lal Chand Bisu ('Bisu’), said that his most memorable day at the office was when they crossed one million paid subscribers. He recalled that when the team first decided to switch from a free app to a paid subscription model, there was plenty of apprehension. The conventional wisdom was that the “Bharat audience” doesn’t pay for goods and services, much less for content. This cohort was happy to consume content, but not to pay for it. Internet companies were historically keen to cater to this audience because it helped to bolster their user numbers. However, no one had attempted to build a business around authentically serving the needs of this group. Hence, there was a wide range of speculative guesses as to how many users would actually stick with KukuFM once the paywall went up.

16 months after launching their subscription offering, they crossed one million paying customers, blowing past even the most optimistic monthly and quarterly targets they had set for themselves. Bisu said this milestone was significant to him because it put the company in the same ballpark as streaming giants like Netflix, Hotstar and Amazon Prime in India. Because of their momentum, he said he could clearly see the path to 20 million users within the next couple of years.

Last up, their COO, Vinod Kumar Meena, offered a slightly different response to the question. He admitted that he couldn’t really point to a single day, but he did have a particular chapter from their story that he remembered fondly. Specifically, around the time they were approaching a million subscribers, he felt like they had crossed a certain chasm. Earlier on in their journey, they would listen to people around them who told them they were making a mistake trying to build for this audience, that they were heading in the wrong direction, that they didn’t understand the Indian consumer.

“At some point, I realised that things had changed. I started telling people - ‘maybe you don’t know how the Indian consumer thinks, let me tell you how the Indian consumer thinks’. That was the biggest change. People used to say ‘you guys are going the wrong way, Indian consumers don’t understand the value of content.’ No, it’s because you don’t know the Indian consumer, thats why you aren’t able to give them anything of value. It was a very satisfying realisation.”

That statement is the reason I’ve spent the last month speaking to the founders, team members, investors, and users of KukuFM - to understand what they’ve done and what they’ve built to earn the trust of this audience, to become such a cherished part of the lives and routines of so many Indians all over the country. Whereas most big companies (both domestic and foreign) have often treated this segment as nothing more than an eyeball farm to be harvested, KukuFM spent five years engaging with their users to understand how to serve them better. Their goal wasn’t to repurpose the attention of this group to serve them ads, it was to understand how to serve them.

As it turns out, in the process of building a platform for vernacular audio content, the KukuFM team stumbled into a roomful of secrets about the Indian consumer, and about India in general. In examining the kind of content that people listen to, and how, when, and why they consume this content, KukuFM has developed as good an understanding of Bharat as any other organisation in the country.

Whereas most startups and large enterprises have largely focused on building businesses for India1, KukuFM is bucking the trend by catering to the roughly 90% of the non-English speaking part of country that is often relegated to nothing more than a statistic.

If you are a regular reader of Tigerfeathers, chances are you don’t fall into KukuFM’s target market. In fact, considering that ~25% of our readers sit outside of India, a good chunk of you will never even use KukuFM.

So why bother reading this piece?

Because the KukuFM story is really an Internet story. It is an examination of what happens when a billion people come online in the blink of an eye, and what that does to their ambitions and worldview. It’s about how the right content delivered in the right format can serve as timber for infinite hopes and dreams. It’s about how digital literacy has stepped in to ameliorate India’s education problem in the most unpredictable of ways. It’s about finding the formula to build a cherished product, and how to build it in harmony with your customers. And, for me, it’s also one of the most inspirational origin stories you’re likely to come across.

So today’s piece will cover:

the journey of the KukuFM founding team,

an exposition of their product and content proposition,

the audio opportunity in India,

and treasured insights on the Indian consumer unearthed by KukuFM

As always, it’s a chunky read. It might take you a couple of sittings (maybe more if you have a tiny bladder), but it’s easily one of my favourite pieces we’ve done so far. If you do make it to the end, I guarantee that you will walk away (many eons later) with a deeper understanding about how to build a consumer business in India; about the size of the Indian Internet market; and about India in general.

Anyway, let’s get going. This is the story of KukuFM.

Origins

“A business is simply an idea to make other people's lives better”

- Sir Richard Branson

Perhaps the most compelling part of the KukuFM story is the fact that at every step of their entrepreneurial journey, the founders have tried to build products that they yearned for in their formative years.

Each of KukuFM’s founders were born in small villages in the north Indian state of Rajasthan, within a 100 km radius from one another. They come from humble backgrounds. Bisu and Vikas’ fathers were both farmers, the most common form of livelihood for folks in these parts. Vinod’s father worked for the Central Government. He spent a large portion of his childhood bouncing around the country to wherever his father’s job took him. The family would return home to his village for the summer harvest season.

The trio grew up in the late 90s and early 00s in India, in a time when the Internet was an alien word. At the turn of the millennium, less than 1% of India (~5.5 million people) had ever been online (compared with ~750 million Internet users and 50% of the country today). Only 3 out of every 100 people even possessed a landline telephone. Some estimates suggested that upto 50% of India lived below the poverty line in the early 2000s. Back then, especially in rural India, your worldview was shaped by the people in your immediate surroundings, and the circumstances of your birth often defined who or what you could become.

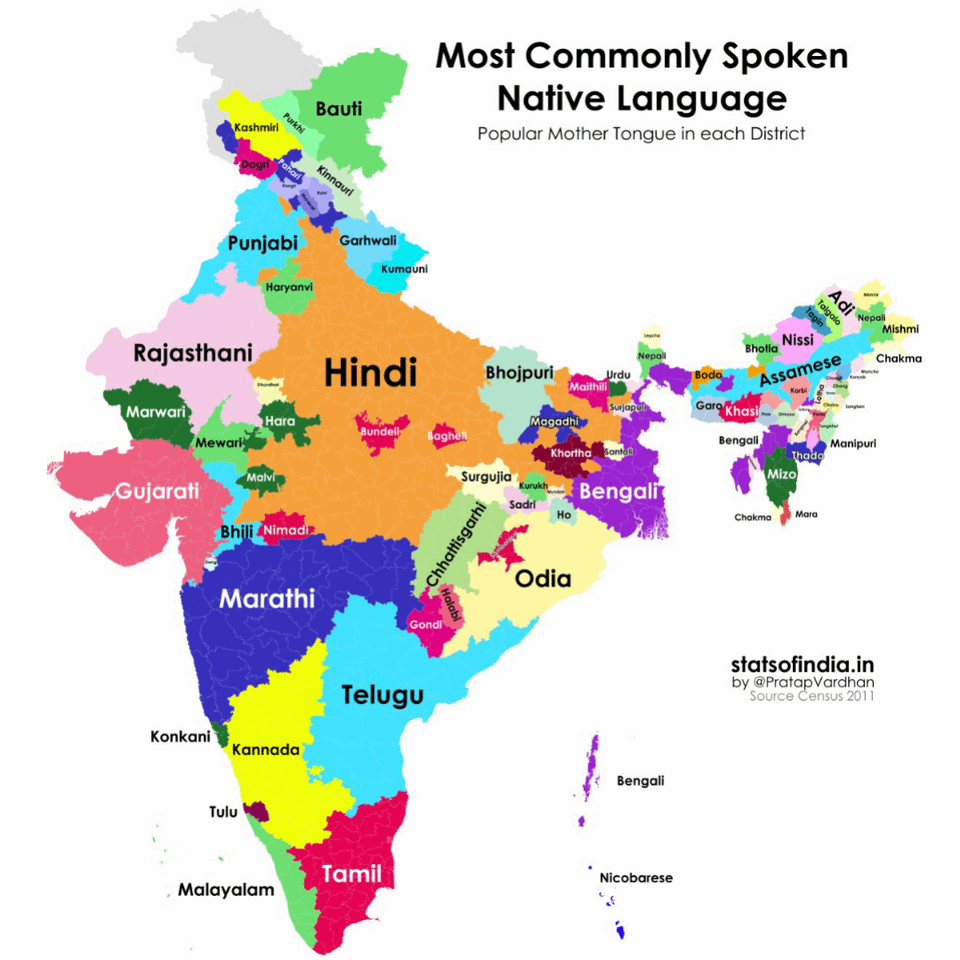

None of KukuFM’s founders spoke any English till late in their teenage years, really only till after they had begun college. Till then, in accordance with the variety offered by India’s unparalleled linguistic buffet, they grew up speaking the patois native to their local districts. Bisu learnt Hindi (one of the two official languages of the Government of India) only in his final two years of high school, which he attended in the nearby city of Sikar. Vinod said that although he attended “English Medium” schools in the cities where his father was posted for work, other than math and science, all the books and the teaching were in Hindi, as is typical in government schools in India. He recalled that language was always an issue growing up because of his constantly changing scenery.

Coming of age in rural Rajasthan in the 2000s, your ambition was constrained to the success stories of the people in your village. Without the Internet to stretch your imagination, there was a meagre set of ‘best-case’ professional outcomes to choose from. Securing a coveted government job was seen as the the ultimate achievement for people looking to improve their lot in life. Bisu theorised that this was emblematic of a colonial hangover in India:

“Indian farmers would always look up to their countrymen in the Indian Civil Service because they were seen as the highest class of Indian society in the time of the British Rule. That’s part of the reason why, in rural parts, government jobs still retain the same level of prestige even today”.

Securing a government job was seen as tantamount to ‘making it’. Whereas a private sector job carried the risk that “anything could happen”, an administrative role with the government brought the assurance of a consistent salary and guaranteed pension. In North Indian villages like theirs, these jobs were a key marker of status. They were the difference between being seen as an eligible bachelor or an unreliable flight-risk. Indian parents encouraged their kids to take these jobs so they could stop worrying about their children’s future. Entrepreneurship wasn’t even remotely on the radar.

For Bisu, his parents had a similar mindset. His father had only been educated till the 6th grade, and his mother hadn’t had any type of formal education at all. They wanted him to finish his studies, find a suitable job with the government, and settle down. But he had other ideas.

“The first thing I can remember wanting to be as a kid was a member of the army, mostly because of all the Bollywood films that came out around this time. In the 7th and 8th grade this changed. I had a wonderful teacher in school that sparked my interest in science. From then on I wanted to be a teacher too, to be able to command that same level of respect. I didn’t think I would ever leave my village.

This attitude comes down to your surroundings. All the ‘success stories’ around us tended to be people with government jobs. We didn’t really see people who had found success in private enterprise because they all moved away from the village. We didn’t interface with any of these people. On the other hand, the people in government roles stayed in the village. They shared the same social circles. They commanded respect in their homes and communities. They were examples we could see and touch and feel”.

“My parents didn’t have the funds to support any further education in science. In Rajasthan, your income doesn’t depend on demand and supply, it depends on the rain. Back then, in the best of seasons, my father could earn Rs. 10,000 [$120] per year. A high school science education started at Rs. 100,00 per year. But although they couldn’t pay for my school, they gave me their blessing to pursue whatever path I chose, as long as I worked hard. For me, that was enough.”

Keeping his promise, his grades were consistently at the top of his class. In the 10th grade, he began teaching science to younger children in his village. Seeing his passion and aptitude for the subject, his village school headmaster offered to pay the fees for his education for the 11th and 12th grade. He was able to finally move to the city to get a proper scientific education, setting him on a trajectory towards tech entrepreneurship. It was during this time that he would learn Hindi and buy his first ever English textbook.

Crossing Paths

Like so many of India’s most accomplished founding teams, they found their professional soulmates within the campus walls of an IIT. The Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) are considered a golden ticket to upward economic and social mobility for much of rural and middle class India. They are world-renowned bastions of technical learning - notoriously difficult to get into - that churn out a conveyor belt of top-of-the-food-chain engineers and founders every year.

Bisu, Vinod and Vikas independently came to the conclusion to apply for admission to IIT after their 11th and 12th grade of school. They put in the hard yards and secured safe passage through the dreaded JEE entrance exam. Each was accepted as a student into IIT Jodhpur, the campus closest to their native homes.

Bisu is two years older than his founding mates, and was part of the first ever batch of students at IIT Jodhpur. The campus was inaugurated in 2008, but wouldn’t be ready for another two years, so he did his first two years of university at IIT Kanpur in the neighbouring state of Uttar Pradesh. By the time the campus was ready, Vinod and Vikas would join him as first year students in the incoming batch of 2010. The latter two were paired together as roommates, and would quickly become fast friends.

Vinod and Bisu met for the first time at an entrepreneurship competition in college. It didn’t take long for them to click. They would start to use each other as sounding boards for potential startup ideas. Along with Vikas and a few other batchmates, this blossomed into a crew of frequent collaborators that spent most of its time knocking around plans for future business ventures. (“That’s basically what the IIT experience is,” said Vinod, “the best thing you get out of it, far more than your studies, is the network you build.”)

Around this time, like so many other aspiring young dreamers in the country, their path would be illuminated by the work of two other former IIT batchmates-turned-entrepreneurs.

When ex-Amazon employees Sachin Bansal and Binny Bansal launched their own online bookstore - Flipkart - in 2007, they would unwittingly become the patient(s) zero for the wave of startup fever that would follow in the Subcontinent. Decades before Shark Tank graced Indian televisions, it was the Flipkart story that made tech entrepreneurship cool for young Indians. Bisu recalled that ordering a book on Flipkart was like a “magical experience”. By demonstrating that a world class e-commerce platform could be built, funded, and scaled in India, they reset the scope of ambition for enterprising graduates.

Whereas previously the brightest engineers at IIT would jostle to secure top jobs at well-reputed ‘IT’ services firms like Infosys, Wipro, and TCS, now everyone wanted to start up. This was compounded by the fact that stories of companies like Facebook and Amazon had begun to invade pop culture. Bisu says that:

“We started using these social media platforms (like Facebook and Orkut) in college and we were blown away. We were curious about who had started these companies, where they came from, how they had made it to India. And we needed these stories because, being the first batch at IIT Jodhpur, we didn’t have any alumni we could lean on or learn from. The Internet was where we went to learn. It was suddenly everywhere in our lives. People were using the Internet on their phones for all sorts of things. We realised even we could use the Internet to make an impact in people’s lives.”

They were sold on the Internet dream. But choosing entrepreneurship meant that they would be forgoing the comfort of engineer’s salary for the uncertain life of a founder, a difficult compromise given their backgrounds. Bisu, in particular, reflected on this choice matter-of-factly:

“If failed, at least I would have acquired knowledge along the way. A job was always something I could revisit. So even the worst case scenario never seemed that bad”.

EasyPrepping

“It is a world of words that creates a world of things” - J M Coetzee

Bisu, Vinod and Vikas all confessed that the hardest part of their IIT experience was adjusting to the difference in language. Each of them had grown up speaking local Rajasthani dialects in their childhoods. They had only graduated to Hindi in their high school years, and were suddenly thrust into an English-first education at college. Bisu said that learning English opened up another world for him:

“Reading English books, listening to lectures in English, having conversations with other students - you realise that your language limits your imagination. We never learnt about things like startups or Internet companies or entrepreneurship while we were growing up because they just weren’t part of our daily vocabulary. Even the little English exposure I had later on was just Hindi books translated into English.

In college I remember reading these biographies of famous Indian businessmen and they made me realise that private entrepreneurship is really the way to make the biggest impact on the country, not government jobs. There were so many people with backgrounds like us that had a hunger for education - to learn more and do more than we had been exposed to in our youth. But only two kids from my school batch left our village to search for better opportunities. Ideas come out of education. I didn’t even know the JEE and IIT existed till I went to study science in the city. It suddenly felt like the Internet gave us an opportunity to tackle this education problem, to cater to people like us who didn’t come from English-speaking backgrounds.”

In a strange way, Bisu felt that he and his co-founders where the right people to solve the education problem in India. Neither of their parents had any commercial backgrounds. They didn’t have any exposure to business or trading or markets. Each of their formative experiences in life so far had been their schooling, their JEE entrance exam, and then their tenure at IIT. Education was what they knew best. Given where they came from, they felt like they had an intimate knowledge of the pain points of the education value chain, and where the quality gaps could be filled.

Many of the same realisations from the quote above would eventually manifest themselves into the product that became KukuFM. But at the present moment, in 2012, they focused on a narrow slice of the same problem. Bisu and Vinod already had some experience with solving for education-on-the-Internet courtesy of a couple of short-lived college experiments. During their time as students, Bisu had built an online platform for student counselling, while Vinod had attempted to create a website for video-based online courses. Neither had taken off.

However, their third attempt at starting up would yield something more substantial. They launched a website called EasyPrep that sought to help students from non-English speaking backgrounds prepare for college entrance exams.

There were six founding members of the EasyPrep team along with several interns from college that worked on the project at various points. Bisu and his batchmates led the charge given they were the first to graduate in 2012. Vinod would join the company full time after his own graduation two years later, while Vikas eventually elected to take a full time role as an engineer with Samsung.

“Our goal was to serve Hindi speakers in India”, said Vinod, “In 2014-15 all the other online education companies were catering primarily to English speakers and English writers. We thought it was strange that only 10% of the country spoke English, yet 100% of the education-based startups were going after this market. At EasyPrep, we tailored our educational material and our platform for a primarily Hindi-speaking audience that largely came from Tier-3 and Tier-4 towns.

The team figured that the surest way to reach their target market was by incubating their solution in government schools, where the quality of teaching often left a lot to be desired. They went door-to-door to every school in Jodhpur first, and then to others within Rajasthan.

“We spoke to anyone who would speak to us - district collectors, security guards, teachers, principals - trying to find the right decision maker for each school. These schools were always under-funded and as a result under-performed. Our pitch was that we could help students raise their test scores. Not only that, if the administrators issued our testing material to their students, we would send individual test results to the administrators, district collectors, parents and teachers, to assess the performance of their children. This was a time before ubiquitous laptops and tablets, so we would spend most of our time manually uploading test scores into our system and sending them out to the schools”.

They managed to painstakingly scale this product across Rajasthan to more than one lakh students. The absence of senior alumni meant that they had no real guidance to scaling their venture and no textbook to follow. They were the first IIT Jodhpur grads to start a company. So far, EasyPrep was getting by on grants from various government bodies and public schemes (“You’re better off raising no money at all than attempting to spend even a rupee of public funding!”)

Three years in, they had made a name for themselves in Rajasthan, and started drawing eyeballs from the wider startup ecosystem.

Topping Up

The first half of the 2010s saw a flurry of activity in India’s nascent ed-tech scene. Dozens of entrepreneurs had sniffed out the opportunity to solve India’s chronic education problem using the Internet. At the top of the pile at the time were two heavyweights - Byju’s and Toppr - founded in 2011 and 2013 respectively. Both had become venture capital darlings and were busy vacuuming up smaller ed-tech startups to add to their formidable empires.

Contrary to the established startup playbook of raising and spending money quickly to acquire customers, the EasyPrep team was doing things the old fashioned way. They hadn’t raised a single dollar of venture capital. They hadn’t even run a single advertisement. They had only just begun fielding inbound calls from private investors. One of these connections - Gagan Goyal from India Quotient - connected them with the founder and CEO of Toppr, Zishaan Hayath, who had caught wind of their progress in Rajasthan. Vinod recalled that:

“Zishaan flew out to Jodhpur to meet us in early 2015. He said he was impressed with our work. He made us an offer to acquire EasyPrep, and for us to join the team at Toppr. He candidly revealed that he had been on the other side of the table a few years prior. His first startup Chaupaati Bazaar had been acqui-hired by India’s largest retailer, Future Group, in 2012. He told us that, similar to his experience, this would be an opportunity for us to learn the ropes of running a company. Once we were ready, we could go out and start our next venture”.

Speaking about the acquisition at the time, Zishaan said that “Toppr’s focus has been on building great products and having EasyPrep team on board gives us more ammunition to execute our plans. This acquisition also helps us reinforce our dominant position as India’s no 1 exam prep platform.”

The team had reasoned that it was a good time to sell. Their ed-tech rivals had raised vast sums of money, and the EasyPrep team was worn out after a three-year journey spent bootstrapping their venture. They had also received a similar offer from another ed-tech rival but ended up going with Toppr, largely because of the rapport they struck up with Zishaan during their conversation.

From their team of six, only Bisu, Vinod, and their co-founder Ankit, elected to join Toppr after the acquisition. It had been a gruelling three-year grind. Each member of the team was from a middle class or lower-middle class background. Vinod explained that everyone had their own financial commitments and priorities to address. Some were feeling the pressure from their families to take up stable jobs. Not everyone had the stomach for another startup adventure. They agreed to go their separate ways. Bisu, Vinod and Ankit moved to Mumbai in the summer of 2015 to start their next professional chapter.

The Ropes

Bisu and Vinod were clear with their objectives at Toppr - learn as much as they could, learn quickly, and move on to their next venture. “We came to Toppr to understand how to run a real company. It was our first real job,” says Vinod. They would later be joined at Toppr by their old college-mate Vikas, who they convinced to leave his gig at Samsung and join his future co-founders in Mumbai.

They started out in the Engineering team, before rotating into the Product function, and finishing their tenure with a six-month stint in Sales. The last leg was the most jarring for the techies.

“Sales is hard,” admitted Vinod sheepishly, “We were entrusted with helping to scale Toppr’s off-line sales business. We would be planted into a new city, tasked with hiring 40-50 people, and left to manage the P&L statement for that location. There’s no glamour in door-to-door sales. It was hard work and long days. We would be in the office early and stay till the last sales agent retired for the day. Once a month we would fly back to Mumbai to regroup with the team at HQ. It was stressful, but it helped us understand operations. Most of all, it helped us understand how a company actually makes money”.

Although it was an exhausting time, the fruits of their next venture were seeded during their long days at Toppr. Bisu recalled that:

“Around this time in 2017, one of my friends introduced me to podcasts. It was an episode of The Knowledge Project with Naval Ravikant. It blew my mind. It was like being able to eavesdrop on a conversation between two really smart people. Till that time to me ‘audio’ just meant music. I fell in love with the format and started replacing all my music-listening time with podcasts. I was never interested in movies or shows, so this format was the closest thing I had found to reading a book on-the-go. It felt intellectual instead of frivolous. I suddenly felt like all my idle hours - commuting to work, lunch hours, jogging in the morning - became productive hours. It felt like I was adding value to my life listening to all these great conversations between interesting people. It didn’t take long before we were all hooked onto podcasts.

Outside of personal developments, this was also a special time for India. Reliance Jio had launched its commercial 4G services in September 2016, effectively inaugurating the Indian Internet story. Hundreds of millions of Indians came online for the first time in the ensuing months and years as a result of Jio’s record-low data prices. Indians weren’t just restricted to browsing either.

In April of the same year, the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) launched India’s groundbreaking Unified Payments Interface (UPI). The new interoperable mobile payment rails gave every Indian with a smartphone the ability to transact online and participate in the burgeoning digital economy. In the course of single calendar year, India had taken several gargantuan strides into the future.

Contrary to the path taken by the West, India skipped the PC/laptop generation entirely. For the vast majority of Indians (especially those living outside of major cities), the smartphone was their first portal to the Internet. Much of Indian society in the ensuring years was rejigged to accommodate the smartphone as the cosmic centre around which people’s lives orbited.

Because of the connection to their hometowns, Bisu, Vinod and Vikas were able to keep tabs with how their friends and families were adjusting to the new digital state of play - how they were navigating the Internet, what new habits they were building, what they felt was lacking about the Indian Internet experience. They were noticing changes in their own digital habits too. The pieces of their next venture started to come together.

Connecting the Dots

As Indians spent more and more time online, the trio were spending more and more time listening to podcasts. They became fascinated by audio as a form factor for content. It was a content format that seemed to chime well with people that were naturally curious and inclined to learn. Vinod even ordered an Alexa speaker from the US to see what the fuss was about. They also noticed that it wasn’t just them, but people all around them that were jumping on the podcast train - either on their commutes, while working or exercising, even just as a means of unwinding at the end of the day.

“We chalked this down to a couple of factors,” said Bisu, “One, people wanted to spend less time staring at screens. And two, audio content gave people the ability to exercise physical freedom. You can’t watch a Netflix show at work or at the gym, but you can listen to a podcast. Audio isn’t really competing with anything else for your time. The other common thread was that people felt like they had many hours of their day that they considered ‘idle time’ or wasted time. By filling these mundane hours with podcasts, they felt like they were enriching their lives. They felt like they were getting their time back as opposed to losing it. That’s how we felt anyway.”

Similar to their time at EasyPrep, they began tugging at the same strings that had stirred their curiosity as university students. “Only 10% of India spoke English, but all the content on the Internet was in English. Only 1% of Indians listened to English podcasts, but 100% of the podcasts available were in English, mainly from the United States. Hundreds of millions of small-town Indians were coming online post Jio, but the Internet wasn’t remotely ready to cater to this audience.”

To be sure, there were other startups attempting to cater to the vernacular market. Companies like DailyHunt and Sharechat had pre-dated Jio and could boast of userbases in the tens of millions. But the content they were providing - short, snackable, often clickbait-y content focused on daily news and entertainment - was not the kind of content that the former EasyPrep team considered additive to the lives of small-town Indians. Bisu says that:

“This type of content is what you associate with instant gratification. It’s what new-to-internet users might consume as part of their first Internet experience. But similar to how people like us graduated from Facebook to Whatsapp to Youtube to now podcasts, we thought that this Bharat audience would also begin looking for content that was a genuine value add to their time and lives”.

By the end of 2017, the were confident that they were on to something. They had also gotten everything they could from Toppr. Bisu and Vinod put in their papers towards the end of the year. Vinod had a slightly longer handover to complete but Bisu was out of the door almost immediately. Vikas would join his friends the following year.

Armed with 100-150 potential startup ideas, Bisu and Vinod would spend the ensuing six months embroiled in a series of experiments to craft the shape of their next venture.

The Making of KukuFM

“We spent most of those six months just chilling.”

The post-Toppr period was the first time the guys had had a chance to take a breather since their college days. They took full advantage of the lighter schedule. They spent their days reading books. They exercised. They researched the global audio industry (particularly in the US and China). They took a trip to Thailand and Cambodia. And then they knuckled down.

“We took two seats at WeWork in Mumbai,” remembers Vinod, “it helped restore some discipline to our routines. We would wake up early in the morning and head to the office. The time off was nice, but we were itching to get back to work.”

They had earmarked three major criteria for their next startup:

It had to be a Business-to-Consumer product, because they hadn’t enjoyed being one level removed from their ultimate users (i.e. students) at EasyPrep.

It had to use technology as a lever instead of relying on a heavy operational set up. They had experienced the difficulty of managing a sprawling operations function at Toppr. They preferred working as a small team to find a solution to a problem, then using technology to scale it rapidly (“small team, big impact”).

It needed to be a product that the founders used on a day-to-day basis, so they could play the role of guinea pigs for their own invention. This would also allow them to use insights and observations from their own lives to inform the product roadmap.

The first product they cooked up was a short video app, that was quickly discarded. The second idea they ruminated over was an advertisement network for audio content in India. Vinod recalled:

“Our thinking was that the hardware for audio was already in place (i.e. phones, cars, speakers, headphones). The content would surely be ready soon, and we already knew people enjoyed listening to audio content because everyone around us was listening to podcasts. Our idea was to build the picks and shovels that would allow audio providers to monetise audio content.”

This idea was eventually shelved too. The problem, they realised, was that an ecosystem for non-music audio content just didn’t exist in India. No one had built an archive for podcasts like many creators had done in the United States. It meant that any potential business targeting this space would have to start from the ground up. For instance, a company like Disney could quickly spin up a video streaming service because it could leverage a decades-old library of existing shows and movies. On the contrary, if you wanted to build a business around audio content in India, you would first need to create the content.

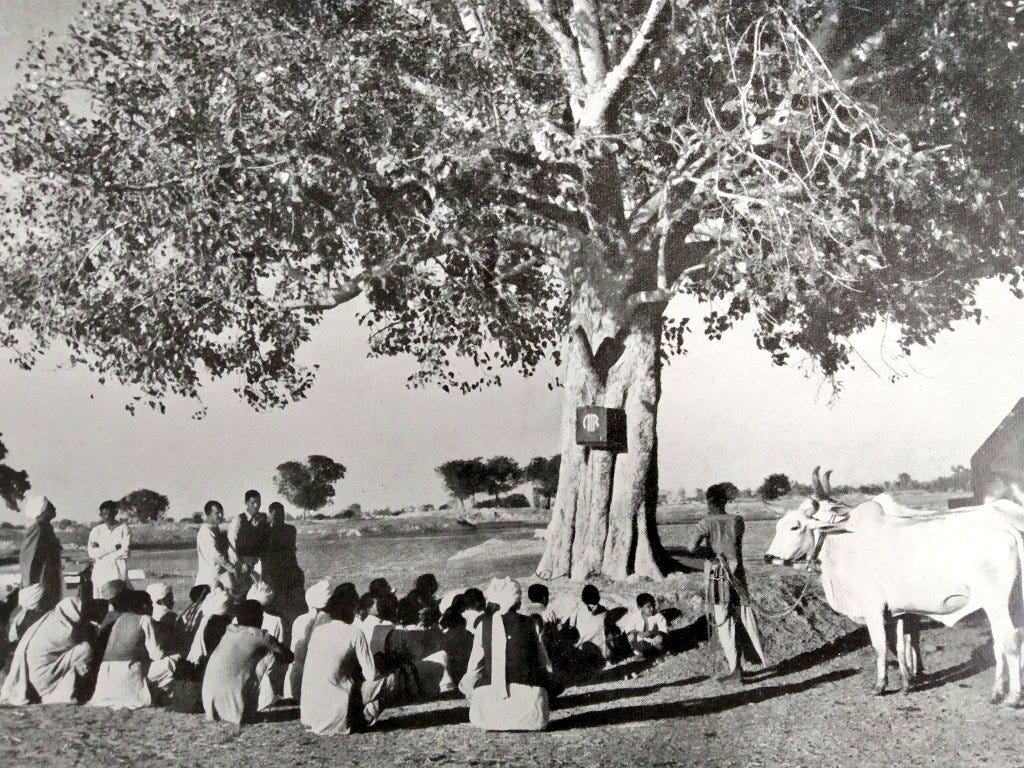

“People in our home towns listened to audio content. But audio just meant radio. And radio generally meant music. Even if there was an interest amongst this audience for high quality podcast-type content, in 2018 there was nowhere to find it.”

They realised that if they wanted to see an audio ecosystem blossom in India, they would need to break ground on it themselves. If they wanted to expose small-town India to the magic of podcasts, they would need to manifest that reality themselves. So they pushed all their chips in to double down on their third idea - to build a podcasting app for Hindi-speaking India.

They sent out the bat signal to their buddy Vikas, who was still an engineering lead at Toppr. Vikas gave in his notice on the spot, and flew out from Hyderabad to join the duo in Mumbai the following morning.

Kuku and Egg

In just a week, the trio spun up an MVP (Minimum Viable Product) for their podcasting app. On the day it was scheduled for release to the app store (in June 2018), they were still struggling to finalise a name. They wanted something short, sweet and memorable, that also had an audio-related connotation.

“We had a shortlist but weren’t fully convinced by any of the options on it”, recalls Bisu, “then Vikas remembered a passage from Kabir Ke Dohe. It referenced the sweet singing voice of the koel [a relative of the cuckoo bird], and the recognisable sound it made. We thought it had a nice ring to it, so we settled on ‘Kuku’ for the prefix, and ‘FM’ as the suffix because it bore a reference to radio.”

To seed their fledgling app with content, they scraped the bottom of the barrel trying to find would-be audio content creators. They reached out to radio jockeys in Mumbai; they found Youtubers that specialised in audio-only uploads (“just a thumbnail and a voiceover”; they DM’d the top 100 most popular Hindi-speaking influencers and creators; they found poets and storytellers on Facebook and connected them with voiceover professionals; and so on. Vinod recalls that:

“We invited all these creators to upload their content onto our platform. Our pitch was simple. We told these people that, similar to the early days of Youtube, first they would need to build up profiles on this platform before they could start to monetise their content. They needed to nurture an audience and garner a fanbase before they could start earning real money. We nudged these creators to upload ‘podcasts’ in a format similar to those made popular in the West.”

With supply taken care of, they turned to Facebook and Google ads to attract their first set of listeners. They had to dip into their savings to acquire these customers, which wasn’t always a comfortable feeling. “We used to sit around after work, relaxing, having a beer, and someone would say ‘hey that beer you just had could have gotten us five more users’,” remembers Vinod.

The first iteration of KukuFM had mixed results. The good news, there was definitely a demand for non-music non-English audio content. “The average listening time on the app was 40 minutes a day per user, compared with 22-24 minutes for music streaming services,” said Bisu. Impressive, considering it was only a bare-bones app that didn’t even require users to log in or create a profile. The bad news - while the engagement was encouraging, user retention was poor. There was a big drop off in users from one episode of a programme to the next.

After a few months, the team decided to tweak their offering to find ways to increase user stickiness. The second iteration of KukuFM was something akin to a ‘Twitter-for-audio’, where people could upload and share short-form audio clips of 3-4 minutes in length. This version didn’t have much more success in convincing people to stick around.

They came to the conclusion that they had so far misunderstood the Indian consumer.

Epiphanies

After extensive conversations with their listeners, the team came away with two foundational realisations as to why their first two attempts had missed the mark:

They realised that Indian consumers don’t like standalone episodes of programming. “Users didn’t enjoy the experience where they listened to one episode of a podcast, but then the next episode was completely different and unrelated to the first. That’s why there was such a big drop-off,” says Bisu. He suggested that, in hindsight, this should have been obvious.

In the US, podcasts had been born from a natural lineage of ‘talk-radio’. American consumers were already used to the idea of listening to long-form conversations on different topics of the day with different guests. Each conversation was like an independent piece of content. So when Apple inaugurated its podcast offering around these ‘capsular’ pieces of content, people were familiar with the experience. “This kind of product would only work for the top 1% of Indians who either lived abroad or had Apple products. These people are native English speakers and prefer listening to US creators in any case. Bharat couldn’t relate to the talk-radio experience. We needed to contextualise the product for our target market”, said Vinod.

On the contrary, Indian consumers had been brought up on a tradition of long-running TV series’ that lasted for thousands of episodes and often spanned across decades. That’s the experience that Indians knew intimately. Instead of getting bored with the same show, Indian consumers enjoyed the familiarity of tuning in to the same characters and themes that had originally drawn them to a particular programme. The KukuFM team realised that Indian consumers detest the labour of content discovery. They like to “Discover once, consume forever.” In the US, people consume podcasts on many different platforms, but mainly discover new episodes and shows on social media. “That culture just doesn’t exist in India”, says Bisu.

The team also realised that, for audio content, people are much less forgiving of substandard production quality. Contrary to watching a video or playing a video game, where multiple senses are being engaged at the same time, for audio you’re only listening with one of your senses. This means that, in the case of users being given free reign to upload short-form audio content, variations in production quality led to an adverse listening experience. “We found that although audio content is relatively easy to make and publish, people have very little patience for a poor quality product”, said Bisu.

It’s worth mentioning here that user centricity is deeply embedded in the DNA of KukuFM. Till today, every member of the team has a responsibility to speak with 3-4 customers everyday to get a first-hand understanding of who they’re building for. In the early days of the company, there was a giant ‘call’ button on the home screen of the app which allowed users to directly connect with a member of the team over the phone. The team found this to be a more reliable way to collect feedback than pestering people with outgoing calls. This methodology proved invaluable to their product development.

“We were able to have thousands of conversations with our users to understand who they were, what they liked, what they did for work, what kind of content they were looking for, why they were tuning in etc,” said Bisu, “In some ways, we built this app together with our customers.”

Armed with new knowledge courtesy of their users, the KukuFM team made a final alteration to their product.

The Arrival of KukuFM

“Anyone who tries to make a distinction between education and entertainment doesn't know the first thing about either.” - Marshall Mcluhan

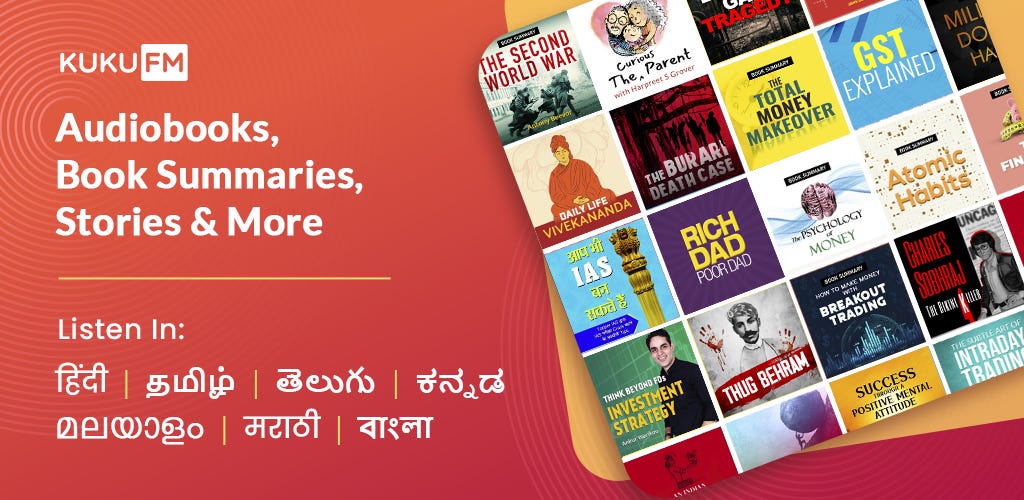

After launching in June 2018, it took an entire year of tinkering and tweaking for the team to coalesce around a content format that worked. They doubled-down on long-form episodic series, where an audio programme would typically be structured into episodes of 10-15 minutes in length. People would end up listening to 2-3 episodes over the course of a day, spending an average of 50 minutes on the app. These series comprised of:

- existing books and audiobooks for which they acquired the Hindi licenses (most of the time these were exclusive licenses),

- original programmes that they produced themselves,

- original programmes that they licensed/commissioned from external creators

KukuFM users could also still upload their own content to the app to build an audience for themselves. However, this would need to pass through a strict quality check before being made available to listeners. The team understood that it was essential to personally curate the content on the platform to ensure a certain standard of production and quality, instead of allowing all user-generated content to reach the final listeners. This felt more professional. It was closer to Netflix than Youtube. They dubbed this format ‘Professional User Generated Content (PUGC)’. Bisu remarked that:

“We found that the highest engagement and listening times on the app were for non-fiction series. This included audiobooks, book summaries, courses, biographies, self-help content, personal finance content etc. We realised that the gap we were filling wasn’t an entertainment gap, but an education gap. The Internet had changed the aspirations of small-town India. Whereas when we were growing up, people wanted to be doctors, teachers, engineers, or government employees. People rarely changed jobs or career paths. Now people from Bharat want to be Youtubers, podcasters, stock traders, and tech founders. The traditional education system can’t move fast enough to cater to this shift in aspirations. We realised that our audience was coming to us in pursuit of knowledge, personal growth, and learning”.

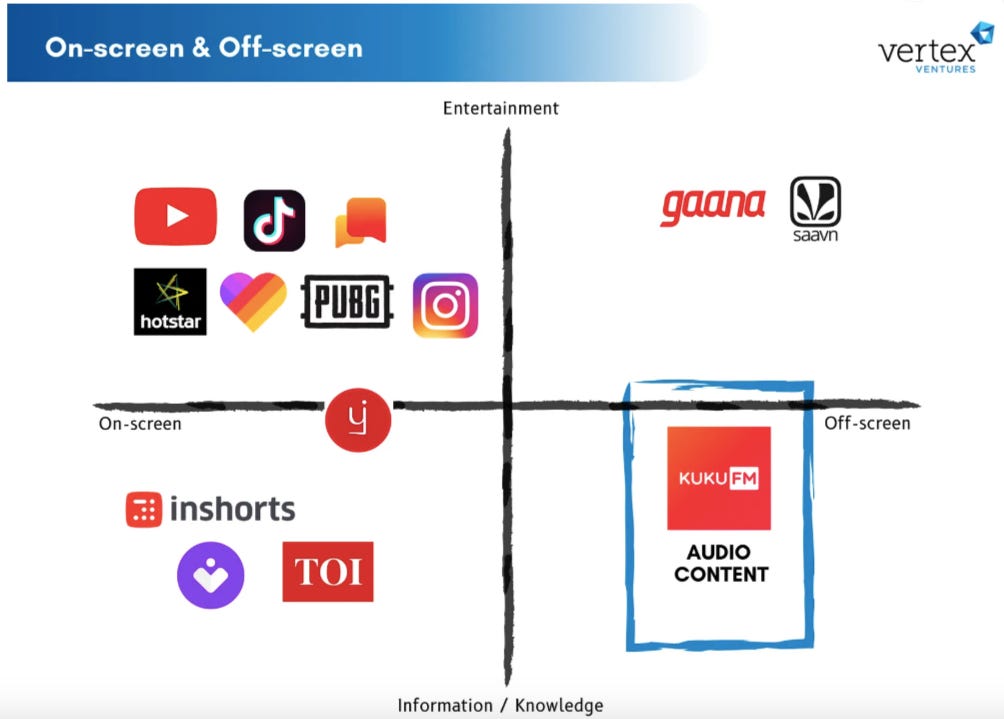

With Product-Market Fit in place, the KukuFM team could push on with more confidence in their mission to ‘make life better off-screen’. They continued to be guided by a desire ‘to offer new, promising and diverse audio content in Indian languages’ to people that came from the same backgrounds as them. Now on the market for venture capital, their pitch was that “In the last 25 years of the Internet, we have optimised for the on-screen experience. In the coming decade, we’re going to see the same progress and innovation happen off-screen.”

In November 2019 they raised an undisclosed first round of funding from a triumvirate of pedigreed early stage investors that included 3one4 Capital, India Quotient and Shunwei Capital. In February 2020, they topped this up with a $5.5 million Series A round led by Vertex Ventures (the VC arm of Temasek Holdings).

Like most content businesses, they saw a bump in user growth during the pandemic (“3X” to be precise). By mid-2020, roughly two years after launching, they had a built a vibrant library of audio content that included popular shows around Indian mythology and spirituality, English bestsellers like Rich Dad Poor Dad and The Psychology of Money, biographies of prominent historical figures, lessons on career planning and investment, and more. The app had several million downloads on the app store. They had a loyal network of audio creators that were building notoriety on their platform, plus an army of Youtube influencers that were spreading the gospel of KukuFM to their audiences.

From regular conversations with their users, they knew that KukuFM was making a tangible impact to the lives of listeners. “People were using our app to prepare for exams and job interviews, to learn new skills and languages, to change their attitude towards money, to improve their relationships and lifestyles, to grow their businesses, to liven up their commutes, and so much more” says Bisu.

They had reached a point where it was time to learn whether KukuFM was a nice-to-have product, or whether they’d actually built something that the Bharat audience truly valued.

Testing Testing…

Thus far, KukuFM had been free to use. They hadn’t attempted to monetise it in any way yet. But in October 2020 they began sending out feelers to their listeners to gauge their willingness to pay for a KukuFM subscription.

“Because of the relationship we had built up with our users, we were able to have frank conversations about what would kind of content would influence their decision to pay for a subscription, how much they were willing to pay, what percentage had the disposable income to pay etc,” said Vinod, “80% of users we polled actually said they were ready to pay for a subscription. Though we took that number with a pinch of salt, we had enough data to suggest that it was worth taking the risk to put up a paywall.

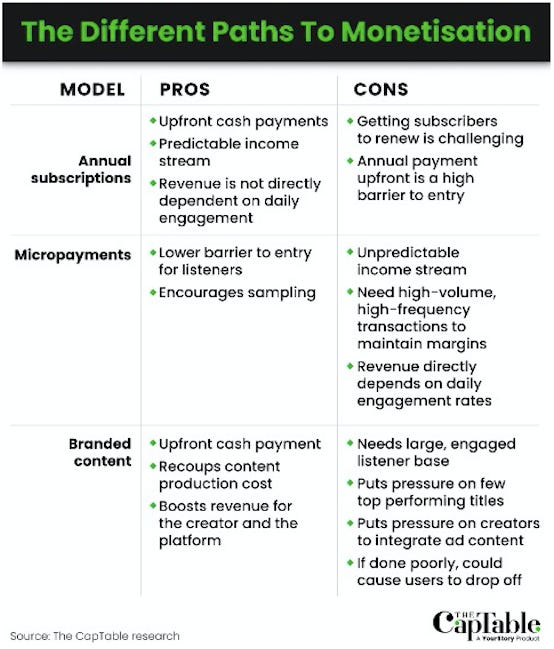

The other angle to this was that we didn’t think advertising was a sustainable monetisation route. We had friends at music streaming companies like Gaana and JioSaavn who told us that the ad market for podcasts was basically non existent. The reasoning was that advertisers were reluctant to offer ads for off-screen content, which made sense to an extent. So if KukuFM was ever going to become a real business, it was likely that we would need to monetise via subscription”.

This was a bold step for two reasons:

1. Bharat isn’t known for paying for content. In the past, India has built up a reputation as a ‘DAU/MAU farm’ where it is easy to rack up hundreds of millions of views and likes and user counts because of our vast population, but it is nigh on impossible to monetise Indian users (because of a relative lack of disposable income for the 90%+ majority of the country). As CRED’s Kunal Shah puts it “Global startups came to India for DAU [daily active users] and MAU [monthly active users], not for ARPU [average revenue per user].”

2. In late 2020 and early 2021, in the arena of high growth tech, the name of the game was growth-at-all-costs. With venture capital flooding into every crevice of the Indian startup ecosystem amidst a historical glut of cheap liquidity, no one was trying to stifle growth by tightening their purse strings. On the contrary, the mandate was to spend quickly to add users, and leverage that rapid growth to justify your next round of funding. What KukuFM were attempting to do by tightening the spigot was akin to bringing a cricket bat onto a football pitch. They were attempting to play a completely different game to everyone else.

“Our investors weren’t fully convinced of this approach either”, says Vinod, “But we felt we needed to test whether we had created something that users really wanted.

In January 2021, after months of teasers, they kicked off their subscription programme. A significant portion of their content library was placed behind a paywall. They team had finally settled on a monthly subscription fee of Rs.99 and an annual subscription fee of Rs. 399 ($1.20 and $4.80 respectively). They sat back and waited to see how their users would respond.

“I remember we had a board meeting at the end of the month”, says Vinod, “This was a few weeks after starting monetisation. At the time we were adding a handful of paid subscribers every day. The total number was still very small, but it felt like we were heading in the right direction.

In the hours leading up to the meeting, we felt like we were at a pivotal moment in our journey. All our preparation for this meeting had been based around overall growth of KukuFM. But the three of us had settled on the idea that our future would be defined by our ability to add paid subscribers, not just to show empty user numbers. That’s what our gut told us. We wanted to build a business. So we made the decision to call each of our board members and requested to postpone the meeting. We let them know our thought process, that we were going to change our North Star to paid subscriber growth. Everything else would be set aside. Despite some alternate viewpoints, they were supportive of our decision”.

That decision wasn’t easy. It meant they had to rejig several internal processes, metrics and objectives. It meant they had to part ways with team members that didn’t fit in with the new modus operandi. The founders said that people laughed at them for talking about monetisation and profitability in 2021, saying they needed to scale quickly to capture their market instead of worrying about paid subscribers. People said that their audience would never pay for content. They decided to tune out the outside noise and let their product do the talking.

Within six months of 2021 that number had creeped up to five figures. They steadily pulled more and more content behind the paywall. They relied on ‘free samples’ to convince users to convert to paid plans (i.e. the first episode of every series was free to listen to, after which the rest of the content was ‘locked’). They also leveraged an extensive campaign of influencer marketing (“All the big vernacular influencers on Youtube wanted to work with us because our product was much loved by their fans”). KukuFM would end the year with 257,000 paid subscribers. They had built the foundations for an enduring media business.

Tested.

In March 2022, on the back of their progress over the preceding 12 months, they closed a $19.5 million Series B round led by South Korean gaming giant Krafton Inc. They were joined in this round by globally renowned investors Founder Bank Capital and Verlinvest.

Reflecting on the rollercoaster ride of the preceding 12 months, Vinod admitted:

“2021 was far from smooth sailing. We were closing in on two years without a fundraise. We finally had revenue coming in but there were a few tricky months in between where we wondered if we had enough money in the bank to make payroll. Thankfully it didn’t come to that. By the end of the year our burn had reduced and our unit economics had become attractive. It was clear that we had chosen the right path. We had proved that people would pay for our content - at scale”.

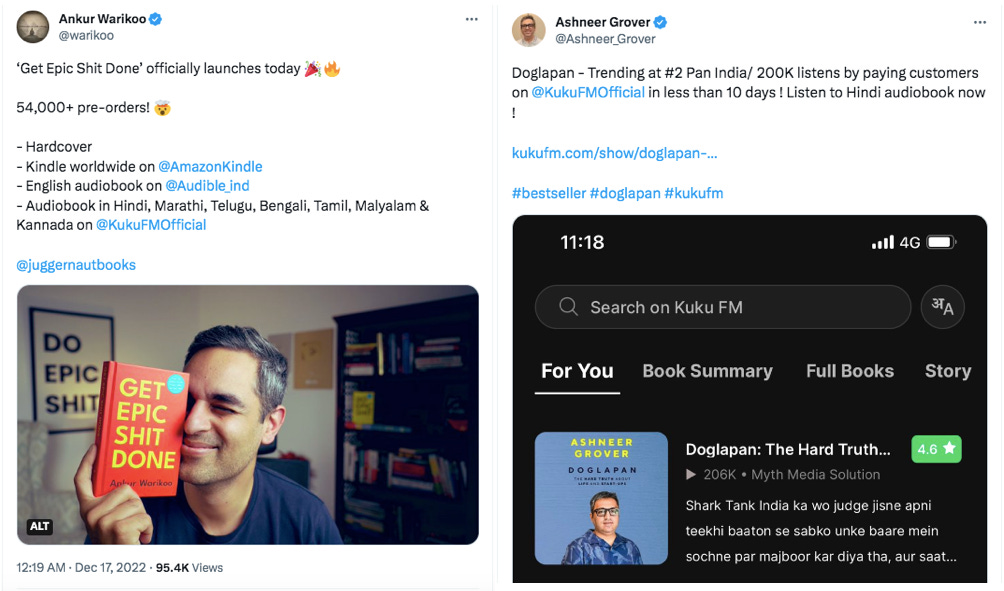

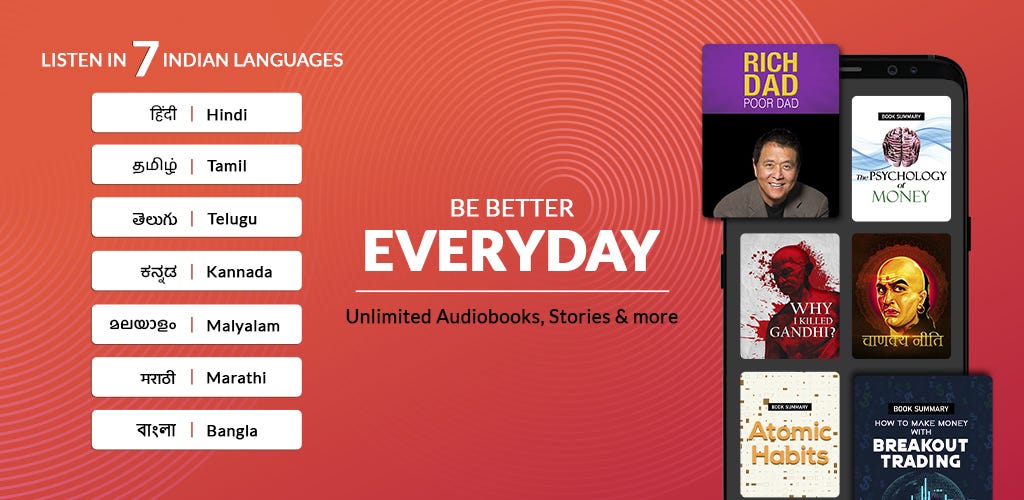

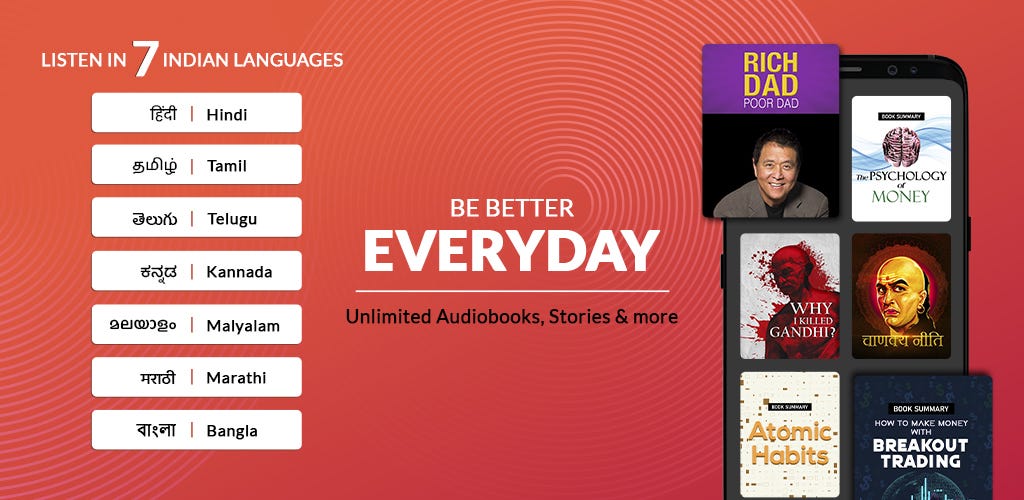

2022 saw them expand into six more regional languages - Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam, Bengali, and Marathi. They continued to tick off major subscriber milestones, crossing 1 million active paid subscribers in June 2022…

…and two million a few months later.

Similar to the ‘paid subscriber’-led blinders they placed on themselves in 2021, their sole objective in 2022 was to improve the unit economics of the company (“Anything that didn’t help us either cut costs or increase revenue per user, we didn’t spend any time on”). This translated to cutting back on discounts, and more than doubling the price of an annual subscription to Rs. 899 per year. They managed to halve the company’s cash burn last year, and anticipate bringing it down to zero by the end of 2023, with the company in position to generate free cash flow by the end of 2024.

Back in 2021 they succeeded in converting 2% of their active listeners into paid subscribers. Today that stands at 10-11%, and “the worldwide average is 3-5% for similar streaming applications, which means we’re in good shape” says Bisu.

At the tail end of last year, on the back of their progress towards building a sustainable business, KukuFM closed a $21.8 million Series B1 funding round led by Fundamentum, the venture fund co-founded by Infosys chairman Nandan Nilekani. They were joined in this round by Paramark Ventures.

The team closed out 2022 as the largest audio subscription company in India. They had earned that status on the back of four years of getting their hands dirty in an honest effort to understand the needs of the Indian consumer.

The Indian Consumer

“People don’t buy products, they buy better versions of themselves”

- Zander Nethercutt

The story of KukuFM merits examination because, in the guise of a simple audio content app, this team discovered what kind of proposition the average Indian consumer deems worthy of paying for. They figured out what constitutes ‘value’ for the ultimate value conscious audience. In their case, it is content that helps people to learn, grow, and improve some aspect of their lives.

To me, many of those same ideas and insights are relevant for anyone attempting to ‘Build for Bharat’ either now or in the coming years, which is to say, anyone attempting to build for a market for 1.3+ billion Indians (or people in other countries at similar economic trajectories).

Bisu puts it like this:

“India is a developing country because the people want to develop. The student wants to get a good job, the businessman wants to expand his business, the mother wants to teach her children, the security guard wants to listen to famous audiobooks during his shift because he never learnt how to read. More than 85% of our users are outside the metropolitan cities. More than 80% of the listening time on our app is for non-fiction content. People aren’t paying us for mindless entertainment, they’re paying us for information that helps them meet their goals. We learnt a core truth about Bharat, which is that Indian consumers are incredibly aspirational, and they are happy to pay for products that get them closer to their aspirations.

That’s not just an empty statement either. Just have a look at a small sample of the top non-fiction shows on KukuFM.

Amongst the most listened to programmes on KukuFM (which includes formats like book summaries, audiobooks, courses and stories) are shows about:

- climate change

- learning to speak English

- improving your diet

- breaking out of a middle class existence

- becoming a Youtube or Instagram star

- how to breastfeed your baby

- how to break free of a porn addiction

- how to apply for a government credit card scheme for farmers

…among others

It’s not the typical content you’d consume in your down time. It’s hardly the type of fare you would find on Netflix or Hotstar. And yet that’s what Bharat is tuning into. For that matter, perhaps tangentially, Bisu also ruminated on why a company like Netflix hasn’t yet managed to crack the Indian market:

“Netflix has around 6 million subscribers in India, which is very small compared to their penetration of markets in the West. From a subscriber perspective, they can only really go after the top 100 million people in India. What they’ve not understood is that for the rest of the country, the television is a family affair. People live in small houses where everyone watches TV together. It is awkward for younger audiences to watch shows that have progressive content around nudity or mental health when they’re around their parents. In Tier-2 and Tier-3 towns you don’t have a lot of personal physical space. You can’t even watch Netflix on your phone in private. That’s why audio works. You’re plugged into your own earphones and your screen is out of view. People can consume content about things that really matter to them”.

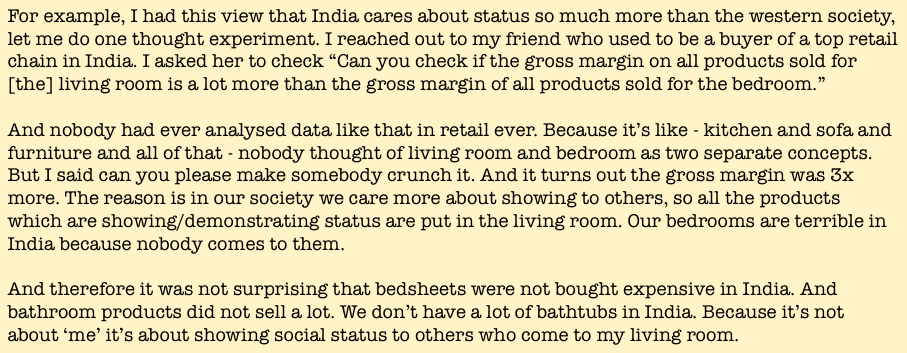

And the content that moves the needle for this audience is ‘aspirational’ content. To phrase this a little differently - it’s not that Indian consumers aren’t value-conscious, it’s that the products people spend money on are those that are typically associated with a perceived rise in status.

“We need to dispel the notion that ‘Bharat doesn’t pay’,” says Bisu, “Even the poorest villagers will spend multiple times their annual income on their children’s weddings or their children’s education, because both these expenditures convey strong social signals. When it comes to the Indian market, people mostly define ‘value’ by its association with status. For us, when speaking to our users, we learnt that acquiring knowledge directly leads to an increase in self-worth. People get happy that they can tell their friends about a certain business concept or historical event, or that certain content enables them to acquire a new skill or qualification”.

The notion that ‘Indians pay for status’ is not new. It is the hidden insight that lurks beneath many of our purchase decisions and marketing strategies, cutting across every strata of Indian society. The products with the highest margins in India tend to be those that can promise the highest return-on-status. On an episode of The Knowledge Project podcast last year, CRED’s Kunal Shah drove home this point by citing an anecdote about furniture prices in India:

It’s a big part of the reason KukuFM can raise subscription prices without fear of losing their customers. From their perspective, they’re not selling content, they’re selling status. Status, and exclusivity. Their Head of Content, Kunj, tells me that in addition to their original shows, 90-95% of the license agreements they have with publishers and creators are exclusive deals. He explained why this has given them the edge over other audio companies in India, and why these companies have struggled to attract paying customers:

“There are six or seven major music streaming apps in India. They have a huge share of the total audio listening minutes in the country. But they all have the exact same library. So what’s the incentive for a consumer to pay for any one of them? They can get all this music on Youtube for free. It’s a tough ask. That’s why these companies have to lean heavily on advertising to build their businesses. In our case, we’re making the claim that what you get at KukuFM, you can’t get anywhere else. We don’t want to play the advertising game because then you’re catering to two sets of customers - your users and your advertisers. We’ve made a clear decision to focus on serving the needs of our listeners. That’s also why we won’t do any branded content with corporate partners either.”

Many of these insights may seem obvious. But they have been hard-earned over a half-decade of trying and testing. Over the last 18 months, since they expanded the number of languages on the platform, Kunj told me that they’ve even been able to observe differences in listening habits for each linguistic segment:

“For all our programmes the main thing we’ve learnt is that it is essential to contextualise content for local languages. It goes beyond just translation. For example, we had to change the relationship between the father and son in the translation of Rich Dad Poor Dad because that kind of dynamic just doesn’t exist in India”.

But maybe their greatest achievement overall as a media company in India has been being able to put a price on content.

“This audience is trained to assume that if it’s free, it’s probably worthless. Our proposition is this - if you want access to quality content, you should expect to pay for it. That’s how you know it has value.”

The team is able to make bold moves because they’ve built trust with this audience. In the founders’ case, Bisu says that they’ve been connected with this cohort of people for a over a decade. Since their time at EasyPrep and Toppr (and KukuFM) they’ve been in constant communication with “students, teachers, parents, government officials”, as well as their own friends and family back home. They’ve seen how the lives and ambitions of ‘small-town, vernacular, blue-collar India’ have changed overnight in the age of the Internet, and that puts them in a unique position to be of service to Bharat in the years to come.

The Future

Almost five years to the day since KukuFM was founded, they’ve crossed three million paying subscribers and are gearing up for another strategic round of funding (a considerable achievement considering India had 3 million paid music subscribers total in 2021). They’ve built the muscle memory of a world-class streaming service. In practice, this translates to a flourishing two-sided ecosystem of creators and listeners. Success in the coming years will come down to keeping both their major stakeholders happy.

On the creator side, Kunj explained that they now have a deep database of creators for different languages and genres as a result of inbound and outbound interest over the years. He manages ‘an army of creator-producers’ across different languages, verticals and customer segments, whose job it is to pitch new shows and then find the right creators for those shows (“We also have Content CEOs responsible for the performance of each piece of content”). Part of their job is also to make deals with publishers and writers to secure the rights for audiobooks that might do well on their platform. KukuFM takes care of the heavy lifting when it comes to production, marketing and distribution.

Their top creators are earning as much as Rs. 3-4 lakh per month on KukuFM (“This works as a revenue share agreement based on engagement. Similar to how Audible does it, the creator gets a percentage of user subscription revenue based on the percentage of time a user spends listening to their programme”). The KukuFM app also allows creators to communicate directly with listeners, so they can assess user feedback themselves, respond to comments, and build a community around their content. Kunj says they’re now comfortable enough in their processes that they can launch a new language vertical within two months.

Kunj joined KukuFM after multiple stints working in mainstream and digital media. He said that his biggest learning was realising they couldn’t just mimic the marketing strategies employed by social media or e-commerce companies:

“For example, we don’t need to resort to cheap hooks to keep our audience engaged. Contrary to Facebook, which needs to keep their DAU numbers high, our audience can derive plenty ‘value’ from KukuFM even if they tune in just for an hour every week. When it comes to e-commerce, a soap on Amazon will always just be a soap. It’s simple to sell. The product is standardised. It’s sold based on reviews and price. Our sales pitch changes based on what we’re selling and who we’re selling it to. We are selling content based on the intangible promise that your life will be better once you consume this thing. And we only have one free sample that we can use to make our case. Our audience is subscribing to get access to our entire library, but it’s likely they’ve made their decision to sign up based on a single programme. Our challenge is to help them navigate through the app based on their goals and starting point”.

According to Bisu, KukuFM’s biggest challenge is to maintain a high bar for content quality while managing the costs of content production:

“For any major media company the biggest cost will always be the cost of content production. Netflix spends billions on content in order to stay relevant. Most of Spotify’s margins go to the record companies they license music from. It’s the same for us. We need to keep adding to our library to incentivise users to continue subscribing. The good part about our approach is that we have the trust of our creators, who know that if they do a good job we’ll make sure to push their content so they can make more money. Our incentives are aligned. And on the user side, our listeners trust that we have their best interests at heart. They see us as partners to grow alongside.”

On the listener side of things, KukuFM is reaping the rewards for their obsessive approach to customer centricity. Because, in many ways, they’ve pioneered the category of non-music audio streaming in India, they’ve been able to learn about customer segments, habits and behaviours that few other companies have been privy to. For instance, Bisu talks about one user interaction from a few years ago that holds immense significance for him and his team:

“A young student called us through the app. He said he had been looking forward to speaking with us for a long time. He said he spent 10 hours on KukuFM every day and he got a lot of joy from listening to our shows. He thanked us and gave the phone to his mother. She got emotional too and expressed her appreciation for helping her son. She said her son was blind. He had a guru who came home for an hour to teach him everyday but aside from that he had no other way to stay engaged with his studies. They used to wait for books and assistance from the government, but couldn’t do much else. We were stunned. We never made the connection that differently abled people would turn to audio content because they had no other choice. India has an estimated population of 34 million people that are blind or living with visual impairment. We hadn’t even considered that we were in position to help this segment”.

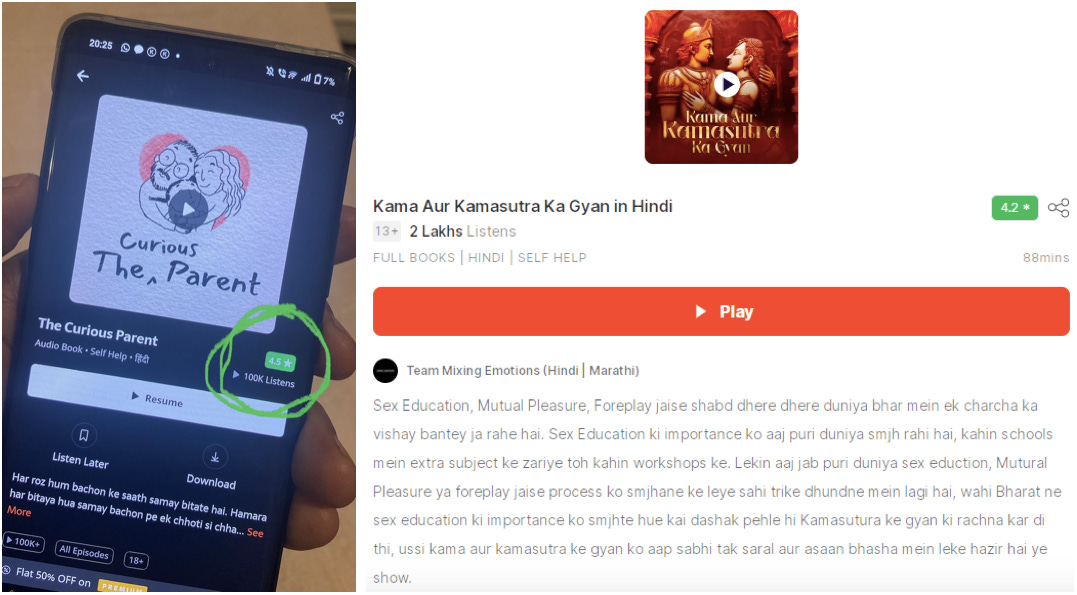

He says it still amazes him that there’s a keen interest amongst the Bharat audience for things like parenting content. “It’s not something I would have even dreamt of when we started,” he says, “It means there’s probably many more verticals for us to enter as we understand the needs of our audience better. Children’s stories, for example, will likely be a big area for us in the future”.

Kunj told me about an experiment they conducted last year where they did an audio show about sex education in Hindi and Marathi, where each episode featured a dramatised story behind a different sex position from the Kama Sutra. The objective was to inform this audience about the importance of consent and mutual pleasure. “It had a very positive response,” he says, “It turns out people are a lot more honest about their desires when no one can see their screen.”

What about the market?

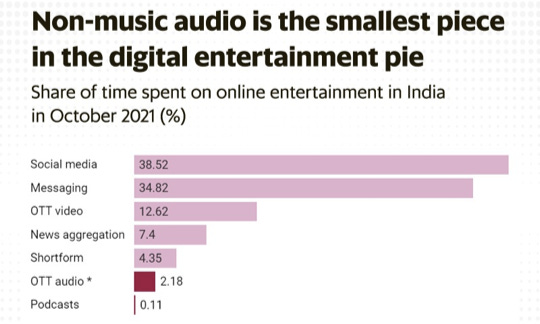

Perhaps the strongest validation of their thesis is the fact that the competitive arena around them has heated up in the last five years. Just two years ago ‘non-music audio’ represented a relatively tiny slice of the overall digital entertainment pie in India.

While it’s hard to find more recent data depicting the growth of non-music audio streams, there is quantitative proof of the growing popularity of the Over-The-Top Audio (i.e. audio streaming) market in India, and particularly the increasing contribution of non-metro cities and vernacular content to the overall quantum of audio streams.

The data that supports the case for ‘vernacular + audio’ can be found elsewhere though. For instance:

Google reported that 90% of Internet users in India preferred to search and navigate the web in their native languages. 80% of India’s digitally monetisable users prefer their content in vernacular languages vs English.

India has the third largest number of podcast listeners in the world (but only 12% of Indians had ever heard a podcast in 2021).

The audio OTT market in India will be worth $2.5 billion by 2030, according to Statista. Our music, radio, and podcast market is projected to bring in revenue of ~$1.7 billion in 2024 per PwC’s Global Entertainment and Media Outlook report

The number of voice searches on Google witnessed a 78% increase from 2021 to 2022. A third of Google’s search queries in India are spoken, 10x the same number in the US. Hindi voice search queries increased 400% YOY in 2021.

According to a FICCI-PwC report, the share of regional language consumption on OTT platforms will cross 50% of total time spent by 2025 (compared with 30% in 2019)

90% of online video consumption in India happens in local languages

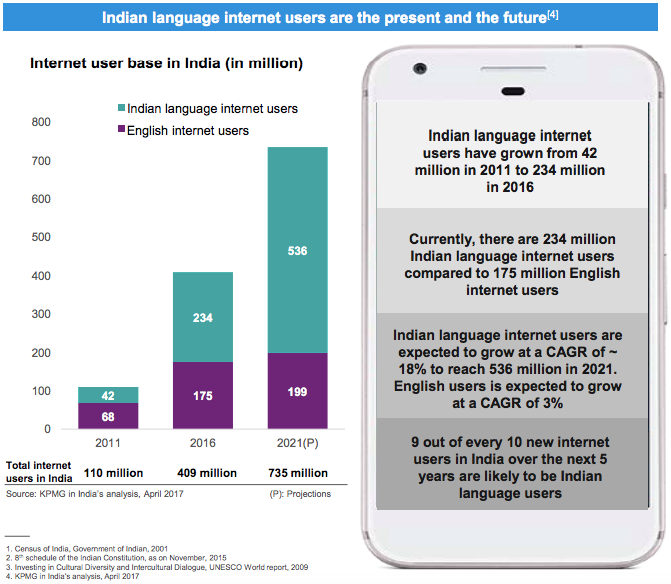

A study by KPMG and Google from 2017 reported that vernacular language Internet users are expected to grow at a CAGR of 18% vs 3% for English users

Spotify reported that 1 out of every 4 users in India was now a podcast listener. They also revealed that there were 7x more local language playlists in 2022 than the year prior. Spotify India now offers 12 different languages and their Indian rival Gaana said that 40% of their streams were for regional music

Audio streaming app PocketFM recently published a survey of consumer audio preferences where they found that 41% of people preferred audio series to other forms of audio content (followed by music with 29%, audiobooks with 20% and podcasts with 10%). They also found that 44% of people were willing to spend on audio content and 65% consumed audio content during their ‘productive hours’.

This year’s Indian Premier League featured commentary in 11 Indian languages, with Punjabi and Bhojpuri streams taking the Internet by storm

Data aside, the clearest marker that KukuFM backed the right horse in the right lane can be found in the actions of competitors - both incumbent and emerging audio companies - who’ve realised that episodic audio series are the surest path to Indian consumers’ hearts.

Vinod broke down the competitive landscape for me. When it comes to competing for listeners’ time, he says they have three main tiers of competitors:

Major global audio players like Spotify and (Amazon-owned) Audible

- “these guys have realised that the audience for traditional US-style English podcasts and audiobooks is tiny. This type of content is too high-brow for 99% of India. That’s why they’ve both started venturing into vernacular audio series.”Domestic music players like JioSaavn and Gaana

- “these companies are now doubling down on podcasts and audiobooks. They definitely understand the Indian consumer. The problem that these apps have is that their main proposition is music. That’s what people come to them for. Music is ‘short-form capsular content’ and audio series are ‘long-form episodic content’. It is extremely difficult to try and be the place for both. Youtube invested a lot in ‘prestige’ series but no one goes to Youtube to watch TV shows. They go to Netflix. The platform is optimised for something different. The algorithm, the UX, the user behaviour and mindset is completely different. That’s why it’s tough for any of the big music players to compete with us from the same app.”Domestic vernacular audio startups like PocketFM, Headfone, STAGE, Pratilipi, Khabri and others

- “these are all great companies tackling the vernacular audio opportunity in different ways. Some focusing on particular genres, some on specific regions, some offering text and video with audio, some stressing more user-generated content than professional-grade content - these guys have good traction but they’re still relatively small. Besides PocketFM. PocketFM is a real competitor. They exist in the same universe as us but they’re approaching the market from a different angle.”

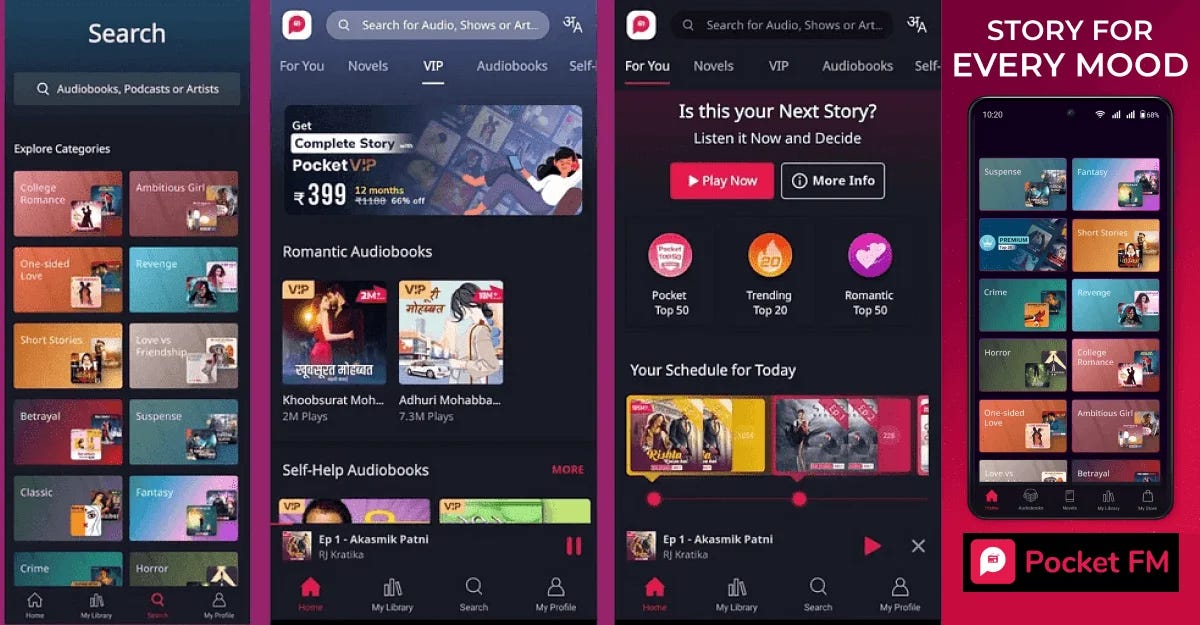

In many ways PocketFM is the Pepsi to KukuFM’s Coke. It was also founded in 2018, just a couple of months after the former EasyPrep team launched KukuFM. Like KukuFM, it offers a platform for long-form audio series in multiple Indian languages. Like KukuFM, they’ve hit serious scale in terms of their userbase (over 80 million), funding ($109.5 million to date), library (over 100k hours) and revenue ($25 million ARR last year). But that’s where the similarities end.

The two companies differ majorly in the kind of content they’re known for; the business model they employ; and what they see as their ultimate market. Vinod insists that these fundamental points of difference mean that they’re not really playing the same game. For instance, unlike KukuFM, PocketFM has made its name on the back of ‘entertainment’ content. Its hit series primarily fall within the realm of fiction - genres like horror, action, drama, fantasy, and romance.

Per the KukuFM team, a significant chunk of PocketFM’s business is in the United States, where they’ve had major success catering to the Indian diaspora that appreciates contemporary entertainment content in their mother-tongues. Instead of burrowing deeper into Bharat, PocketFM has its eyes set on international expansion. It is already present in 20 countries and appears to be targeting the 32 million-strong Indian diaspora living around the world.