10(ish) Products That Capture How India Is Changing

On charts, cheetahs, and snapshots of an 'India in Pixels'

Hey folks👋

Welcome to the 290 new Tigerfeathers subscribers who’ve joined since our last piece.

Eric Hoffer once said that “In times of change, learners inherit the earth, while the learned find themselves beautifully equipped to deal with a world that no longer exists.” He also once said “I hang onto my prejudices, they are the testicles of my mind.”

I’m not sure how either of those quotes applies to us, but we have a soft spot for non-sequiturs here at Tigerfeathers. So if you’re not offended by the paragraph above, click here to subscribe👇

This edition of Tigerfeathers is brought to you by…COZM

COZM is a Mumbai-based startup that helps creators launch their own podcasts. They’re a small team of podcast junkies that believes in the long-term potential of the medium. COZM takes the hassle of audio production off your hands and lets you focus on showing up and making good content. They managed to convince us to launch our own podcast too👀 If you’ve been curious about podcasting and don’t know where to start, give them a shout. They’re offering every Tigerfeathers subscriber 50% off on the production fee for your first episode. Get started on your podcast adventure here.

If you’re interested in sponsoring a future edition of Tigerfeathers, get in touch with us on Twitter (or by replying to this email).

“India has known the innocence and insouciance of childhood, the passion and abandon of youth, and the ripe wisdom of maturity that comes from long experience of pain and pleasure; and over and over again she has renewed her childhood and youth and age.”

- Jawaharlal Nehru (the first and former Prime Minister of India)

If you’re a longtime reader of this newsletter, you know that most of our work has been an attempt to paint a portrait of a country in flux. For almost three years now, we’ve presented colourful vistas of a nation that has been touched by technology, illuminated by smartphone light and propelled by the undertow of digital data. Each Tigerfeathers piece has been an attempt to decode a piece of the India puzzle.

And today’s edition is firmly on brand.

First, some background. Last November I read a blogpost by Rex Woodbury - one of my favourite Internet writers - on ‘10 Charts That Capture How the World Is Changing’. In his piece (and its 2023 sequel) he showcased a variety of charts and graphs that were emblematic of broader societal themes, mostly in the United States. They offered a tantalising glimpse into trends around homeownership; the digital habits of young adults; the internationalisation of pop culture; a rise in loneliness in America; the adoption of AI; and everything in between. All together, the compilation made for a tidy 10-course meal.

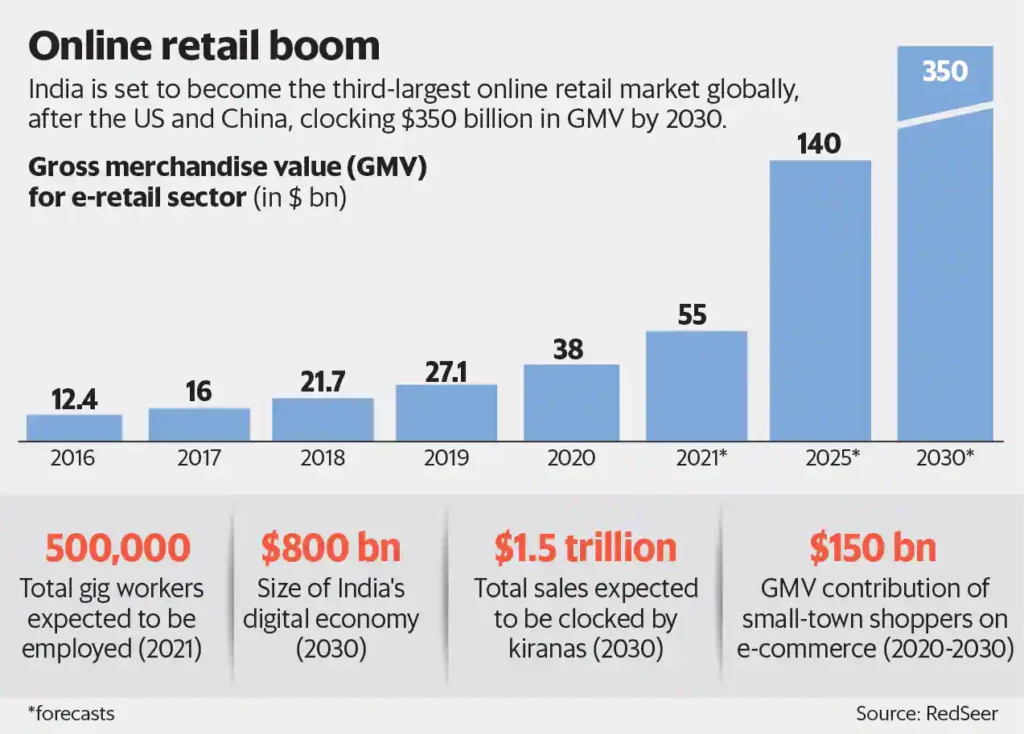

I was curious what that would look like for India. In other words, were there 10 charts that could do justice to India’s digital metamorphosis over the last fifteen years? Could you distil the modern Indian growth story into a series of statistical flashcards? And would it be a faithful representation of the unique virtues and challenges inherent to India in 2023?

I thought it was worth a shot. So in my initial attempt to compile this piece, I scavenged around for charts that nailed the brief. Ideally, I wanted a list that balanced ‘serious’ economic data and lighter cultural commentary. Bonus points for charts that would be interesting to both our Indian audience as well as our readers from outside the subcontinent…

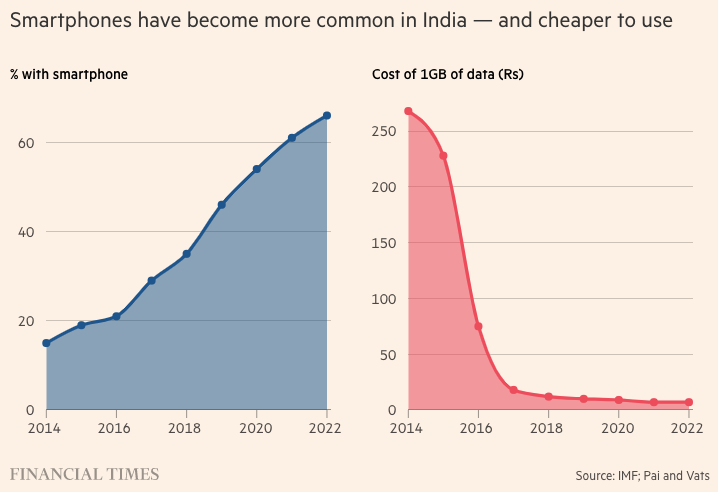

Something like this one from the Financial Times about escalating smartphone ownership and plunging mobile data costs in India.

Or this one from the National Family Health Survey/Stats of India about the ownership of household items in India. The number of smartphone users in the country is set to cross one billion by 2026.

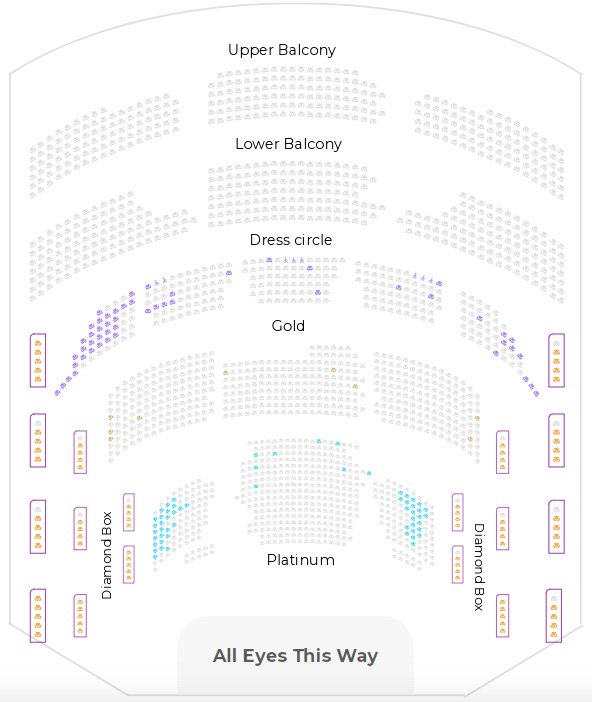

This (seating) chart from the Sound of Music, the first ever Broadway production to be performed in India, currently playing at the recently inaugurated NMACC in Mumbai.

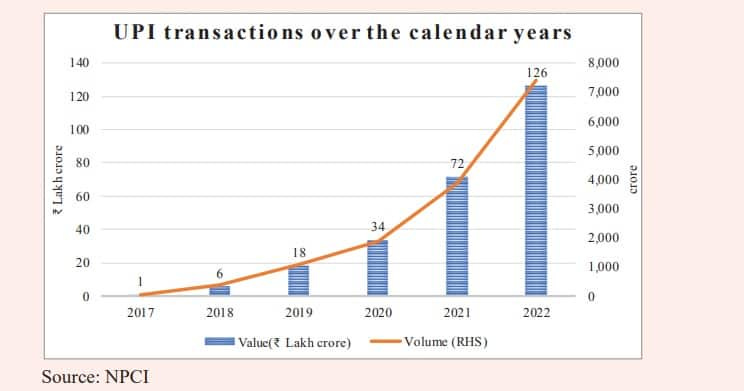

This graph from the Economic Survey of India (2023) depicting the exponential growth of India’s groundbreaking real-time mobile payments platform - UPI (Unified Payments Interface). UPI payments accounted for 52% of all digital transactions in India in 2022.

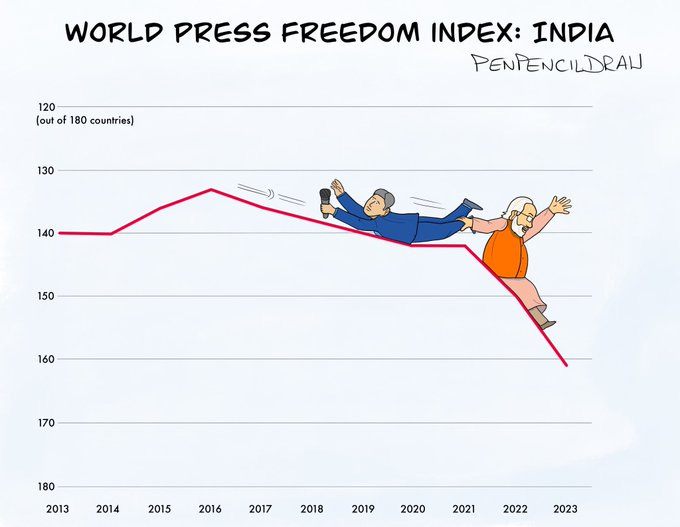

This pair of beauts from @PenPencilDraw about the worrying decline of press freedom in India…

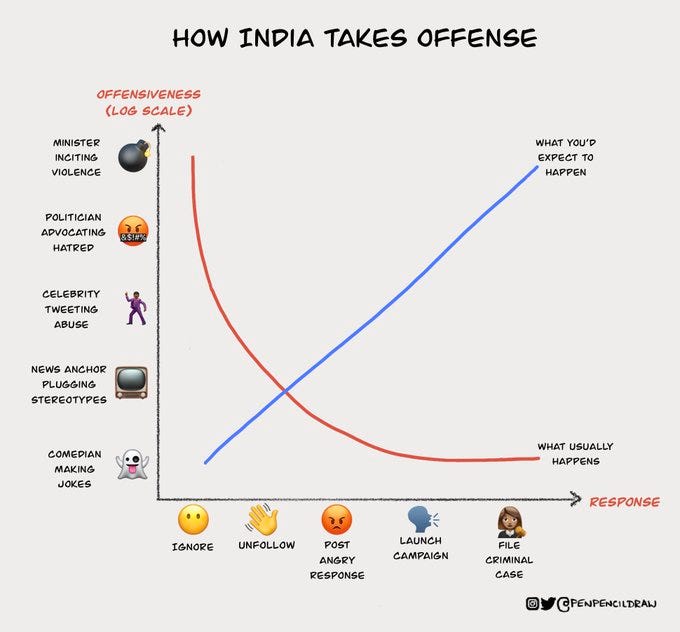

…and this masterpiece that illustrates how India typically takes offence (some things don’t change🤷♂️).

You get the idea.

Anyway, like I said up top, it would have been fun to present a vision of 21st century India through a montage of pretty diagrams. I still have several other serviceable charts on things like airports, exports, highways, bank deposits, tigers and Oscar-winning songs that would make for great additions to this piece.

But halfway through my research process, I realised that many of the themes I wanted to explore were best illustrated not via charts but rather by the stories of entrepreneurs and startups that were building companies in those same areas.

For instance, I was looking for data on the $65 bn meat consumption market in India, but I figured I could make my point better by highlighting the story of Licious, an 8-year old company which has built the “highest valued D2C start-up in India” by selling fresh meat and seafood products online. Licious is a perfect example of the kind of narrative violation I was hoping to ensnare for this piece, having built a billion dollar company selling animal protein in a country that people would typically (and wrongly) assume skews overwhelmingly vegetarian.

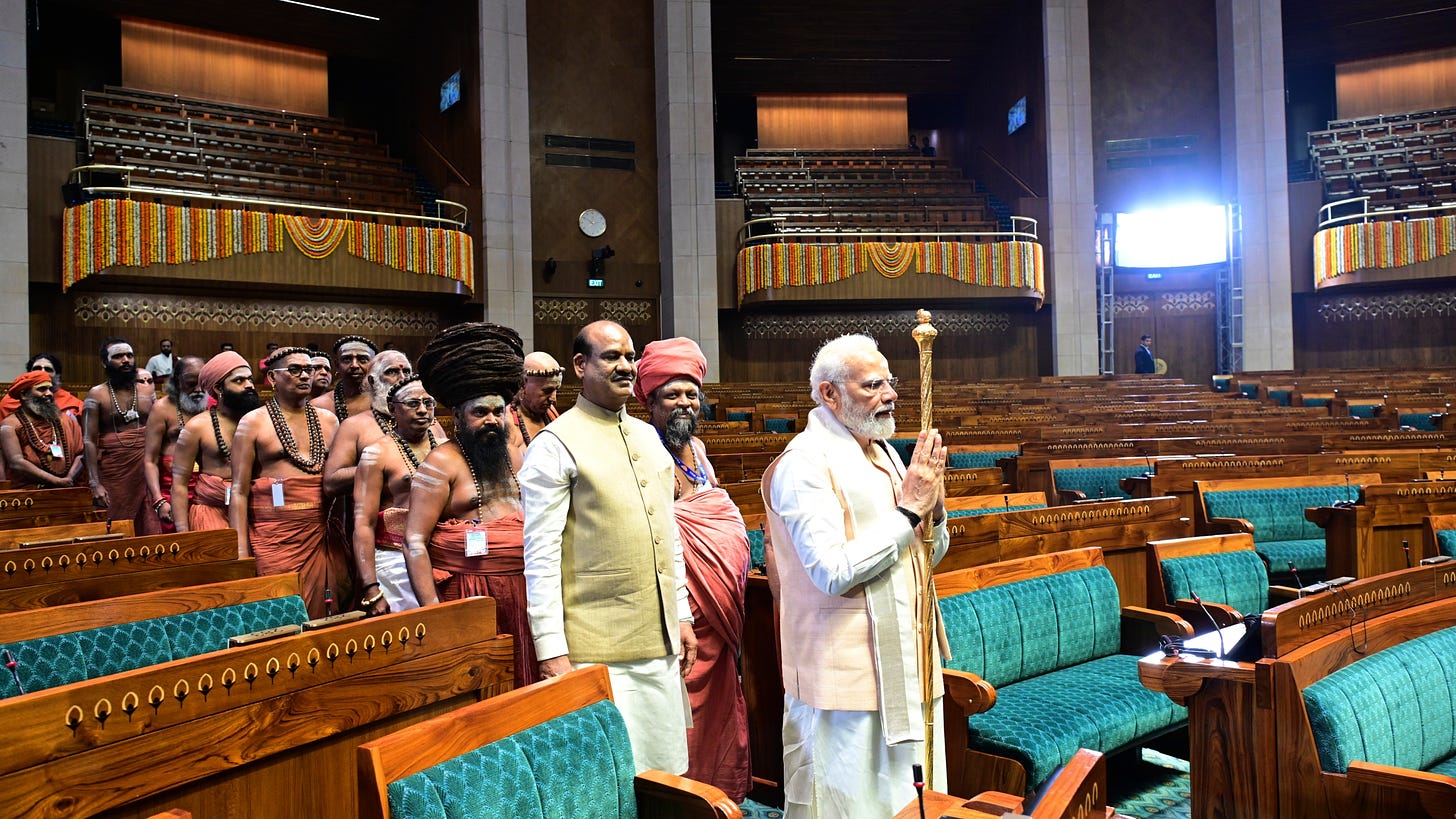

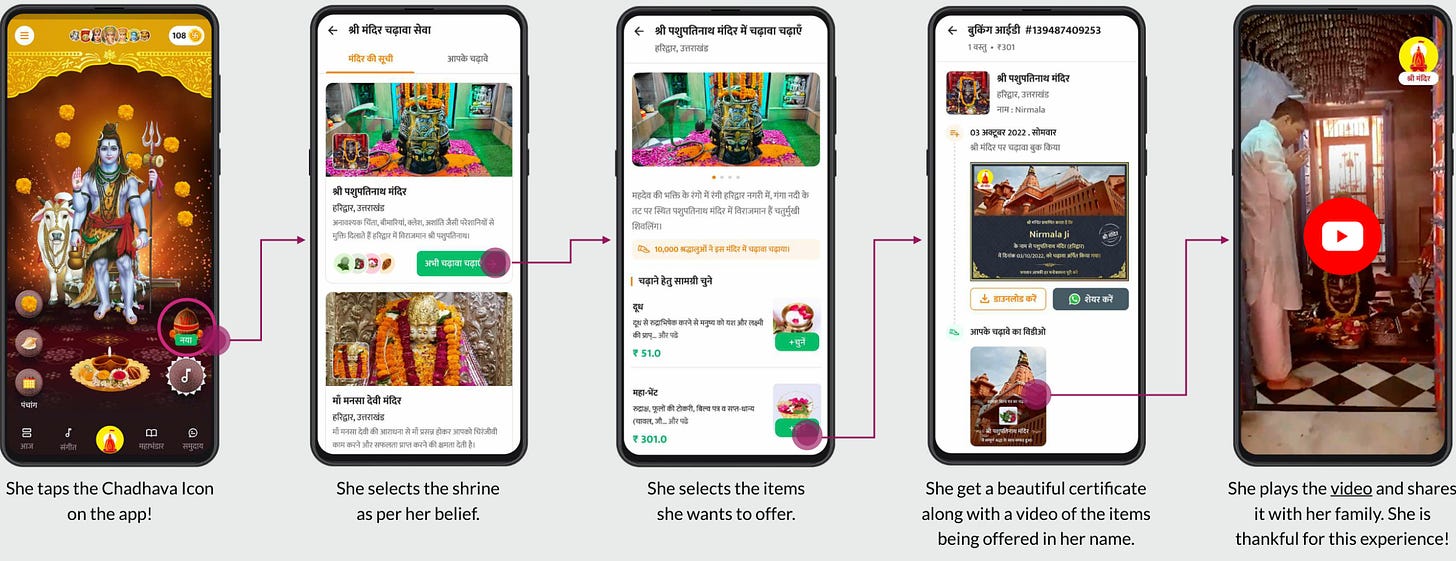

Or take the example of religion in India. You could perhaps argue that religiosity is an unavoidable casualty of a ‘smartening’ populace, incompatible with the bells and whistles of the modern world. I could probably show you data that argues both ways. But in reality, tradition and technology are proving to be strangely congenial bedfellows. This is illustrated perfectly by the story of SriMandir (which we covered in March), a uniquely Indian application that aims to ‘put a temple in every phone’. SriMandir’s 10 million+ users invalidate the claim that devotion and digitisation can’t peacefully co-exist.

Similarly, you’d struggle to find an area of Indian society that hasn’t been touched by technology. We probably still take for granted how different our routines were just 10 years ago when UPI didn’t exist, Jio hadn’t yet launched, and 1000 rupee notes were still a thing. So, given that our newsletter typically covers stories from the Indian startup ecosystem, I thought I could make my case better by focusing on the products that capture how India is changing.

“We shape our tools and thereafter our tools shape us”

- John Culkin (A Schoolman’s Guide to Marshall McLuhan)

Before we begin, first, a few disclaimers:

This is a ‘shallower’ piece than our usual fare. It’s more of a mood board than a manuscript. Closer to Buzzfeed than Ben Thompson. You can think of it as a tasting menu of India in 2023.

This isn’t just a list of products. It’s really a mish-mash of products, themes, sectors and innovations that deserve their own chapter in modern Indian folklore. Our only qualifying criteria was that each of these topics should be interesting enough to warrant a future deep dive.

You don’t have to read it in one sitting. Treat it as a 10-part anthology as opposed to a 10-act Shakespearean play.

Mostly, I wanted this piece to serve as an answer to the question “what can I read to get a flavour for what’s happening in India?” If you like this format, let us know and we’ll do it more often.

Anyway, let’s get going. Here are the ‘10(ish) Products That Capture How India Is Changing’🇮🇳

1️⃣ Tea☕

Are you familiar with the "greatest single act of corporate espionage in history"?

It has nothing to do with Apple or Samsung or HP or Volkswagen, or any other modern corporations you read about in the news these days. No, this act took place in the 1800s. It involved a British horticulturalist named Robert Fortune. The theft in question targeted the secrets of tea cultivation in China.

The British were looking to reduce their dependence on Chinese tea in the wake of the Opium Wars. They had fallen in love with ‘the beverage’, and couldn’t rely on a hostile Qing dynasty anymore to fill their cups. They realised they could puncture the Chinese monopoly on tea by initiating the cultivation of tea in their territories in India (parts of which shared a similar climate profile to China). So in the mid-19th century, the East India Company recruited the services of Robert Fortune (AKA ‘The Tea Thief’). He spent years on a covert mission across the border, using a variety of tricks and disguises to smuggle plants and farming techniques out of China to seed the growth of tea in India. That’s how the story of tea in India began, as a consequence of colonial conflict.

Before the East India Company realised the commercial potential of tea as a commodity, tea was mainly consumed in India as a form of medicine, to help with mild ailments like headaches and indigestion.

It was only in the early 1900s, with the mushrooming of roadside stalls and Irani Cafes in every corner of the country (coupled with savvy advertising that bordered on propaganda) that tea became ‘India’s drink’. The culture of tea drinking was intertwined with the nationalism and enlightenment that characterised India’s freedom movement in the lead up to Independence.

These days the culture of tea drinking has been given a facelift, appropriately reflecting the heightening aspirations of India’s modern working class. Tea isn’t just a way to start the day in 2023 India, but a place to to continue the conversation. Startups like Chai Point and Chaayos (started in 2010 and 2012 respectively) have enrobed the humble cup of chai in a slick modern avatar, replicating the same formula that Starbucks employed to ignite the culture of coffee drinking in the West.

As the two leading chains in India’s tea cafe scene, they’ve become mainstays in retail hubs all over the country, gobbling up considerable venture capital along the way to aid their rapid expansion. Their outlets provide a ‘premium’ alternative to tea brewed at home or at traditional roadside stalls. Their menus feature unconventional (sacrilegious?) flavours like ‘aam papad chai’ and ‘rose cardamom’ chai; they’ve even built IoT-enabled robots to standardise production. Following the contemporary QSR playbook, these companies are experimenting with deliveries, B2B sales, franchises, and vending machines, using creativity and technology to build commercial empires around ‘India’s drink’.

Along the way they’ve been joined by plucky competitors like Roastea, Chai Sutta Bar, Chai Break, Chai Kings, Teabox, MBA Chaiwalla and others, each of whom is adding their own twist to the tea cafe experience. Many of India’s major tea producers have also expanded downstream, opening boutique cafes and bars to offer the perfect sanctuary for tea connoisseurs.

Not to be left behind, even the original roadside chai stall has been fitted for an upgrade. One of the major success stories from the last season of Shark Tank India was a company named Mahantam. Started by two brothers in their early 20s, Mahantam makes an automatic tea glass-washing machine for roadside tea stalls that can wash 15 tea glasses in 30 seconds. Their pitch was only the second time in the season where every shark on the panel joined forces to invest.

Whatever your preference, there’s enough room in India’s tea industry for everyone to flourish. India consumed 1.2 billion kg of tea in 2022. It is said that 80% of all Indian families drink tea. Despite the fact that we are the second largest producer of tea in the world (after China), it is telling that 80-90% of this tea is consumed domestically. It is as close to a narcotic as you’ll find in India without alerting the authorities, and the ritual of tea drinking is one that shows no signs of going away anytime soon.

One of the major themes of Indian enterprise in the 2010s was a shift from informal to formal, from unorganised to organised. You see it across different industries and verticals - perhaps most notably in India’s cherished cup of chai.

2️⃣ IPL🏏

The Indian Premier League is the closest thing that India has to a contemporary religious festival. The deities may take a different form, but the intensity of devotion is undeniable.

For two months between March and May every year, no one gets anything done India tunes into the IPL. You’d struggle to find a television set (or smartphone) that isn’t adorned with colourful broadcasts from the biggest club cricket tournament on the planet. Still only in its 16th season, the IPL is speed-running the process of building an iconic sports league that already stands shoulder-to-shoulder with globally renowned (and historic) entertainment franchises like the English Premier League, UFC, F1, the NFL, NBA etc.

It is already the second-most valuable sports property in the world when measured by the price of media rights. The price of broadcasting an IPL game comes in at $15 million per game compared to the $36 million per game for the NFL. Over 450 million unique viewers in India tuned in to the IPL last year, reaching roughly half of the total television sets in the country. Given that 93% of all sports hours watched in India are cricket, the IPL is the closest thing we have to a unifying cultural force. However, contrary to the Superbowl, which serves a similar function in the US, the IPL isn’t just one game. It’s an entire two-month span where the attention of India (and the global cricketing audience) is affixed on the same stage.

The IPL’s inclusion on this list isn’t because of its ascendance as a globally significant sports property. It’s because the IPL itself has become a reflection of India’s evolution since 2008 (when the league was inaugurated).

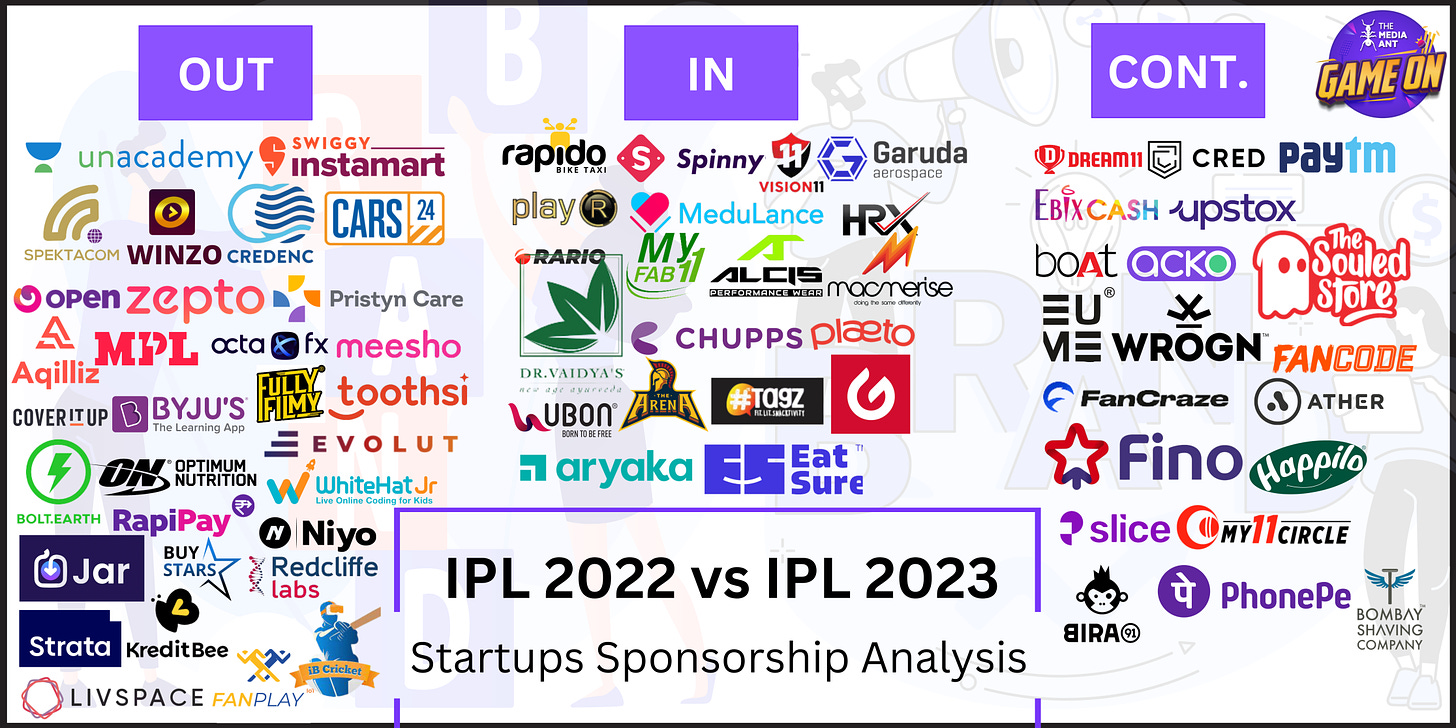

You see it in the rotating cast of corporations that have scrambled to place themselves in front of the IPL audience. These companies - paying sky high ad rates - are those at a stage in their trajectories where it makes sense to swap money for eyeballs.

Last year, with India coming off a record year of venture capital funding in 2021, IPL screens and jerseys and stadiums were peppered with logos from startups that were flush with cash and eager to force their way into public consciousness.

The year before, in the midst of a historic bubble for high-risk assets, the IPL saw crypto startups dominate Indian airwaves for the first time. Practically mirroring the Indian government’s capricious position towards the regulation of crypto, these startups were nowhere to be seen in 2022, electing to play nice with the regulators’ request for more responsible marketing of their products.

As the global funding winter blew towards the subcontinent, Indian venture capital funding dropped by a third to $23.9 billion in 2022. The modus operandi for young companies flipped from offence to defence, with startups prioritising survival and profitability instead of pageantry and promotion. This was evident in this season’s IPL, when Indian startup participation retreated proportionally with the decrease in overall funding.

Marshall McLuhan once said that “Ads are the cave art of the twentieth century.” As far as India goes, if you want to know where the attention of our country is shifting, the writing is usually on the walls (of the IPL).

3️⃣ Sex🍌

Despite India being the land of the Kama Sutra, it wouldn’t be unfair to say that conventional attitudes around marriage and sex can be conservative, at best, and repressed, at worst.

But they’re also changing. If you look past the censorship and pearl-clutching that characterises much of our mainstream discourse, you can find tangible evidence of a thawing prudishness in Indian society, particularly amongst the younger generation. What’s more encouraging is that this changing tide has even spilled over to ‘Tier-2’ and ‘Tier-3’ India, outside the relatively liberal bubbles of India’s major cities.

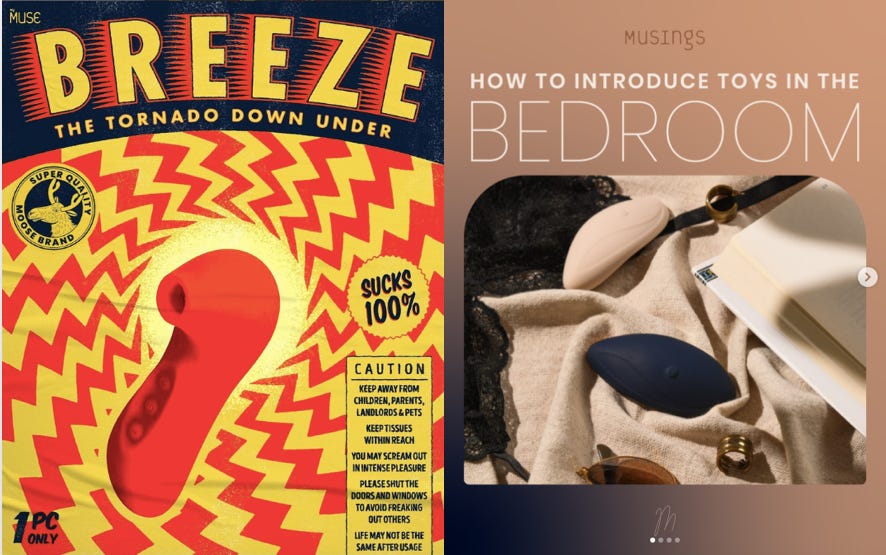

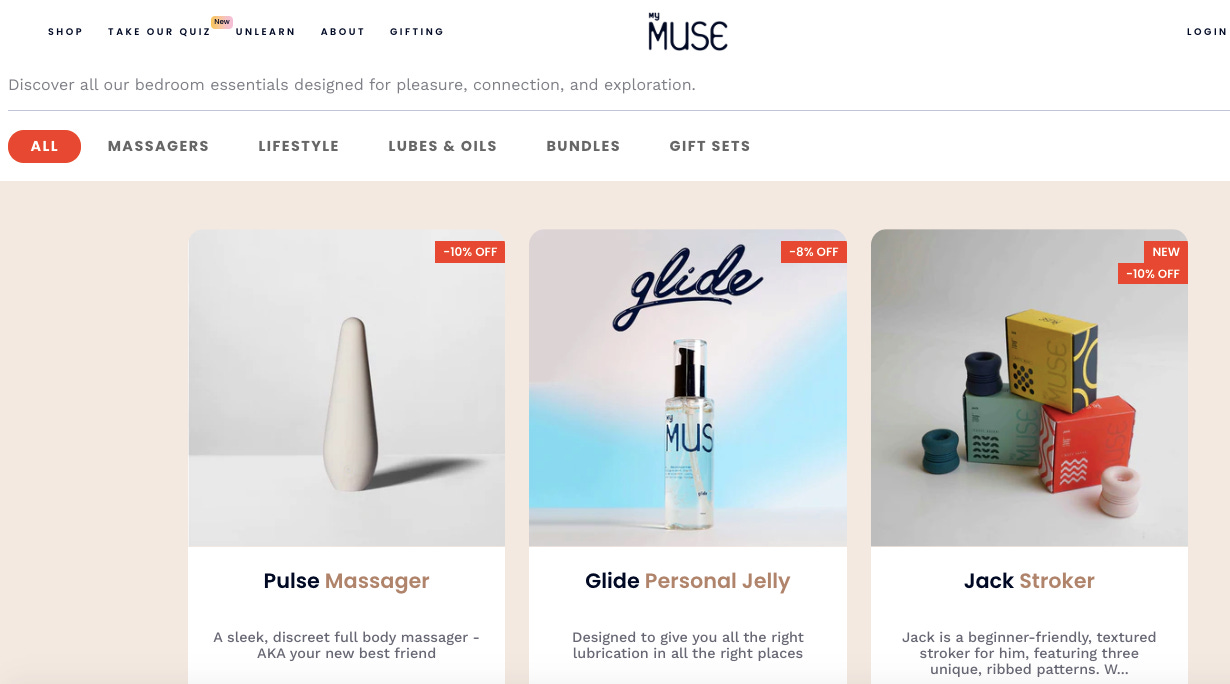

It’s not just the process of finding romantic partners that’s changing, but the celebration of romance itself. A number of startups have broken ground in India’s nascent sexual wellness and sexual health space. These companies - like MyMuse, The Sassy Thing, Manzuri, Besharam and others - are crafting world class products for the Indian bedroom, using playful marketing and modern design to normalise the ‘right to pleasure’ amongst Indian consumers.

MyMuse, a venture-funded startup founded by husband-and-wife duo Anushka and Sahil Gupta, is building ‘India’s first luxury intimate wellness brand’. They say that 20% of the demand for their range of premium toys, massagers, oils, lubricants, candles and games comes from Tier-2 India.

They say that “Through MyMuse, we’re giving Indians access to safe, high-quality, and discreet products for their bedroom experiences in a way that celebrates intimacy. We believe that sexual wellness is a fundamental part of one’s overall wellness.”

According to Allied Market Research, the Indian sexual wellness market was valued at $1.2 billion in 2020, and is estimated to reach $2.1 billion by 2030. As far as removing the taboo around sex goes, we’re not there yet. But we’re coming.

4️⃣ Squares💸

The off-line retail experience in India has been invaded by an army of squares.

First came the infantry - i.e. the QR code.

And next, the cavalry - i.e. the soundbox.

Both are uniquely Indian in their implementation.

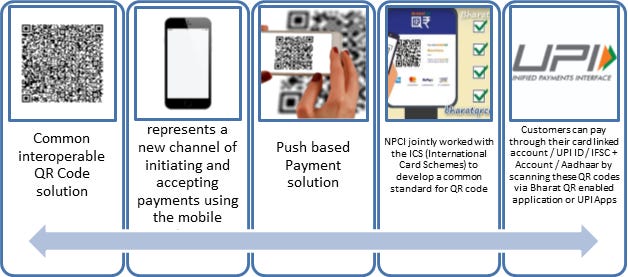

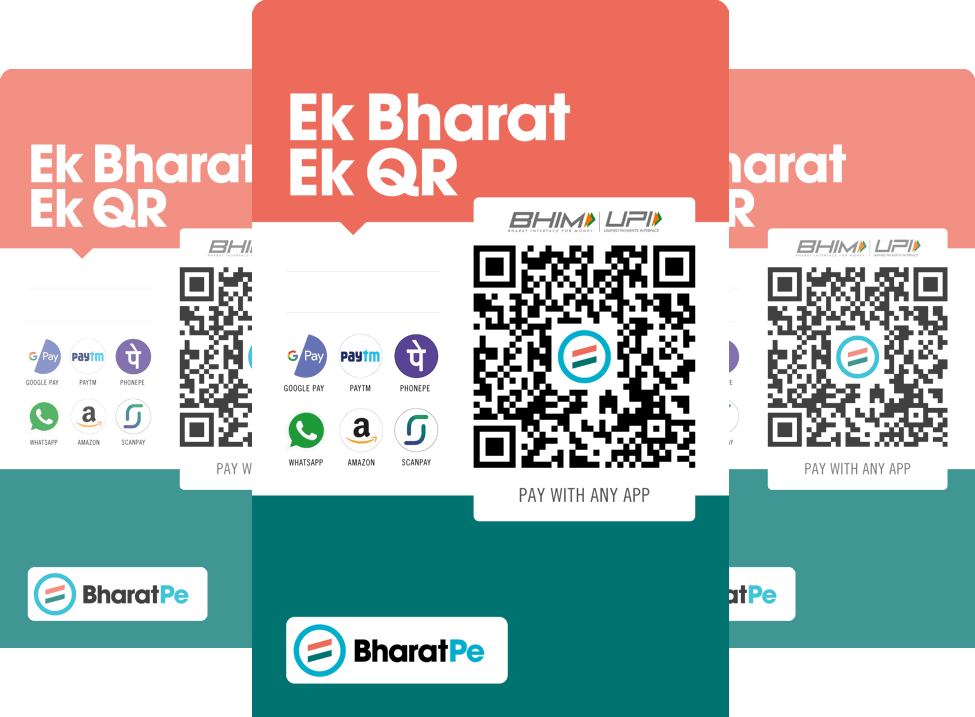

QR (Quick Response) codes only became ubiquitous in India in the latter half of the 2010s once the adoption of UPI took off post demonetisation. Before then, if anything, the retail storefront was really a single player game. PayTM was the only fintech player promoting QR codes as a way for merchants to accept payments via its proprietary digital wallet. This was consistent with how QR codes proliferated in China in the 2010s. Heavyweights like Alipay and WeChat made extensive use of these codes to expand the acceptability of their digital wallets, competing fiercely to keep users within their individual walled gardens.

In India, however, once the country awoke to the ease and interoperability of UPI in 2016, startups like PhonePe and Google Pay began plastering their branded QR code stickers onto storefronts, nudging users to make UPI payments via their own apps. The problem was that UPI’s interoperable architecture meant that consumers could use any UPI-supported app to make payments into any UPI-enabled bank account. It didn’t matter whose sticker it was or what app was being used to scan the code. The QR code became a universal language for payments.

In a post-UPI world, payment apps in India became commoditised overnight. Incumbent digital wallet players had their lunch stolen by newer competitors that doubled down on UPI. This created a turf war at the storefront. Newcomers like BharatPe (launched in 2018) realised that it made more sense to lean into this interoperability rather than pretend it didn’t exist. They offered merchants a single QR code that they could place at their storefront so that consumers could make UPI payments via any of the 140+ UPI-supported apps on the appstore. BharatPe skipped the expensive reward-heavy consumer side of payments all together. They realised there was more value to be gained from acquiring a large merchant base and then cross-selling them with financial services.

With regulators maintaining that UPI should come at no cost either for merchants or consumers, it meant that fintech players had to reckon with an uncomfortable truth - it was nigh on impossible to build a business solely around retail payments in India. The issue is that in the years since, the dependence on UPI has continued to increase with every passing month, growing from 20 million transactions in 2017 to 60 billion transactions by FY23. Every retailer from the tiniest roadside coconut seller to the spiffiest department store now sports a QR code to accept UPI payments. As a business, ignoring UPI today means you’re probably leaving some chips on the table.

This has created a situation where the leading UPI payments companies - PayTM, PhonePe and Google Pay - are constantly on the search for creative avenues of differentiation and monetisation.

Enter the ‘soundbox’ - effectively a lightweight speaker that instantly ‘announces’ the receipt of a payment so that a busy storekeeper doesn’t have to manually check whether a payment has been made. They also help to guard against QR code fraud (in case someone replaces your sticker with their own) or instances of fake payment screenshots from customers. They are ‘smart’ devices that support multiple languages and multiple modes of payment. They’ve come to represent the newest front for retail warfare in India.

PayTM was first to the party in 2020 (with the PayTM Soundbox). They were followed by BharatPe’s Speaker in 2022 and PhonePe’s Smart Speaker soon after (with Google’s Soundpod set to join the party this year).

These speakers aren’t just cute accessories, they’re big business. They usually come with an upfront set up cost and then a monthly rental fee. This adds up when you account for the volumes being done by the market leaders. PayTM and PhonePe have already sold 6.8 million and 2.2 million of these devices respectively. PayTM claimed that its Soundboxes processed 5 billion transactions in FY22, accounting for 38% of the company’s net payment revenue. The company made $150 million from Soundbox subscriptions in the third quarter of this financial year. Each of these companies believes that these devices are key to retaining their merchant base and widening the surface area to cross-sell lucrative products like merchant loans.

The shift from cash to mobile to stickers to soundboxes essentially unfolded over half a decade. If you want to know what the future of retail looks like, you could do a lot worse than loiter around the counters of India’s corner-shops.

5️⃣ Marketplaces🛒

The bazaars of India once served as the cradles of commerce for much of the ancient world. Bustling markets nestled in historic cities like Calcutta, Surat, Bombay and Madras came to represent vibrant hubs of trade. Their gravity lured in craftsman, traders, bankers and merchants from exotic lands, all looking to grab a piece of what the world had to offer.

In the 21st century, the sights, sounds and smells of the great Indian bazaars have been replaced by the polish, efficiency and scale of online marketplaces. This transition is largely credited to the hustle of two ex-Amazon employees, who would catalyse an entire generation of tech entrepreneurship when they started their iconic venture in 2007.

When Sachin Bansal and Binny Bansal co-founded their online bookstore (Flipkart) from a two-bedroom apartment in Bangalore’s Koramangala district, they couldn’t have foreseen that their journey would come to serve as a proof-of-concept for the entire Indian startup experiment.

“...there were ups and downs, but I think history will remember us for two things. To consumers, Flipkart will be remembered as the company that created Indian ecommerce, that brought to the average Indian’s doorstep a wide range of affordable, quality products. The other is Flipkart’s contribution in creating the startup ecosystem in India. Hundreds of startups focused on solving for India have been inspired by Flipkart to create products that improve people’s lives. Flipkart has instilled confidence in budding entrepreneurs that world-class tech-product companies can be built in India as well. These, I think, are our greatest achievements.”

- Sachin Bansal and Binny Bansal (Flipkart co-founders) in a 2018 interview

Before Flipkart, there was no startup ecosystem, and no startup culture. The two Bansals proved that there was a market for online commerce in India. Flipkart pioneered many of the product features and commercial tricks that Indian Internet companies employ ubiquitously today.

Cash-on-delivery, 24x7 customer service, deep discounts and cashbacks, same-day deliveries, no-cost EMIs - all were added to the Indian retail lexicon courtesy of Flipkart. Billion dollar funding rounds and billion dollar ‘unicorns’ became commonplace. Flipkart’s $20 billion (ish) acquisition by Walmart in 2018 proved to be a bell-weather for Indian e-commerce, validating that we now had the infrastructure (payment rails, logistics services, supply chain networks, smartphones, cheap data), the market depth and the consumer maturity to create world class digital product companies in India.

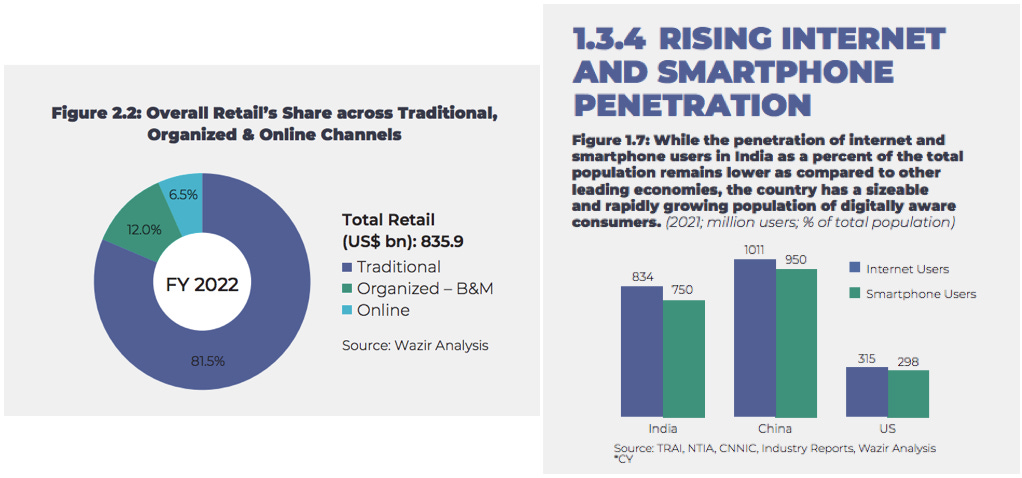

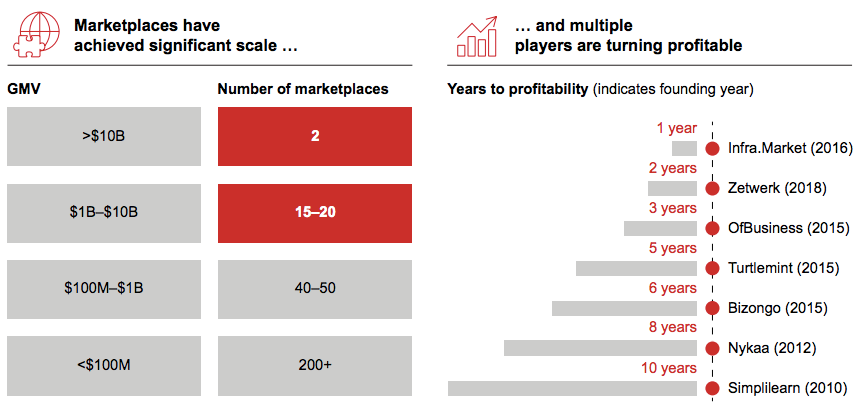

16 years since Flipkart created the template for online commerce, today there’s a marketplace for everything. In India in 2023, if it can be sold, there’s a good chance someone has tried to sell it online. There are more than 300 funded digital marketplaces operating today, collectively doing more than $100 bn in Gross Merchandise Value (GMV). As of today, 20 of these marketplaces are recording more than $1 bn each in GMV. Investor confidence in these businesses has grown, with notable players like Nykaa (fashion and beauty), Zomato (food discovery/delivery), Policybazaar (insurance), and others reaching the IPO stage in the last couple of years.

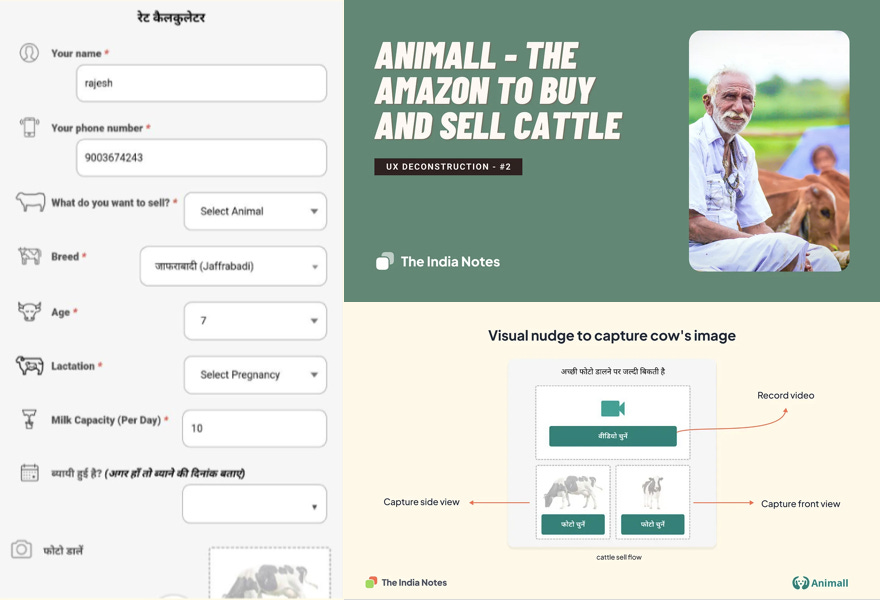

Across consumer (B2C) and business (B2B) segments, there is a colourful roster of platforms that are filling important roles in India’s digital economy. These companies have helped improve access to goods and services across the country (eg: Nykaa, Myntra, FirstCry, Lenskart). They’ve stitched together fragmented supply chains (eg: Shiprocket, Blackbuck). They’ve widened financial inclusion via digital loans and insurance products (eg: Bankbazaar, Policybazaar). They’ve helped to employ millions of gig workers (eg: Ola, Amazon, Swiggy). They’ve helped service professionals and small businesses expand their earning capacity (eg: Urban Ladder, Pepper Content, Indiamart, Jumbotail). They’re creating bridges between rural and urban India (eg: Ninjacart, GramCover). And they’re finding their way into areas you might have assumed were immune to digitisation.

"In the labyrinth of an Indian bazaar, one can find the universe encapsulated, where the ordinary mingles with the extraordinary, and every wish is within reach."

That was as true many millennia ago as it is now. The difference is today you don’t need to travel many miles on foot or on camelback. Today you just need to unlock your smartphone.

6️⃣ Space🚀

“There are some who question the relevance of space activities in a developing nation. To us, there is no ambiguity of purpose. We do not have the fantasy of competing with the economically advanced nations in the exploration of the moon or the planets or manned space-flight. But we are convinced that if we are to play a meaningful role nationally, and in the community of nations, we must be second to none in the application of advanced technologies to the real problems of man and society.”

- Vikram Sarabhai, ‘Father of the Indian space programme' (1919-1971)

We’ve come a long way from the wide-eyed early days of the Indian space programme. Dr. Vikram Sarabhai and Dr. Homi Bhabha (the architect of India’s nuclear programme) inaugurated the Indian National Committee for Space Research (INCOSPAR) in 1962 under the aegis of Jawaharlal Nehru. The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) was later formed on 15th August, 1969.

The US and USSR were by then already embroiled in a furious race to see who could launch humans and objects into space before the other. India was still only 15 years removed from Independence when the two visionary physicists ushered us from the bleachers into the arena.

While the US and USSR competed for geopolitical bragging rights, the focus of India’s nascent space programme was inward, to help develop solutions that addressed our national development priorities. For instance, the Satellite Instructional Television Experiment (SITE) was an experimental communications project launched in India in 1975 to explore whether mass satellite broadcasts could be used to educate rural Indians located in the hinterlands of the country. At the time it was hailed as ‘the largest sociological experiment in the world’.

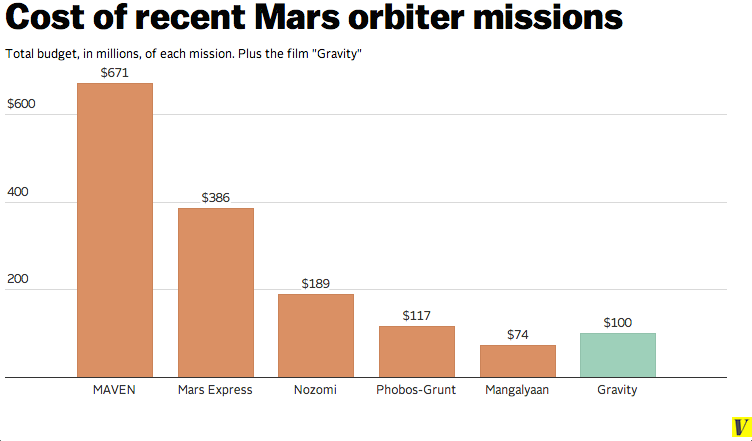

In the subsequent decades since 1962, ISRO crossed a number of milestones on its way to becoming the sixth largest space agency in the world. The first Indian satellite - Aryabhata - was launched from the Soviet Union in 1975; Rakesh Sharma became the first Indian citizen in space in 1984; Chandrayaan-1, India's first lunar spacecraft, was launched in 2008; We built our own indigenous satellite navigation system called NavIC (to reduce our dependence on GPS); and so on. These efforts were a product of the ingenuity, foresight, and parsimony of Indian scientists, punctuated by the fact that India’s Mars Orbiter Mission in 2013 cost less than the budget of the film Gravity (a movie about people in space).

Like many areas of the Indian economy, our space sector has flexed its full potential in recent years as the guardrails to private participation have been lowered. The importance of private entrepreneurship to our ambitions in space has now been formally enshrined in the Indian Space Policy 2023…but its not like our entrepreneurs were waiting for a special invitation.

ISRO’s openness to private collaboration has led to a Cambrian explosion of space-tech startups in India. These companies are on their way to becoming vital cogs in the global space economy.

The likes of Pixxel and Galaxeye have developed hyperspectral and multi-sensory satellites that can capture granular data about the surface of the earth; Companies like Skyroot and Agnikul are democratising satellite launches by building cheaper (and even 3D-printed) rocket components; Bangalore-based Bellatrix is prototyping the development of satellite thrusters — small engines that help satellites align themselves in space and reach their intended orbits; Digantara has created an orbital monitoring platform to better detect space debris to improve our situational awareness in space; Dhruva Space - India’s first private space company - offers a ‘full stack’ space engineering platform that can manage every step of a commercial satellite launch programme. The list goes on.

Across manufacturing, launch services, communication and software development, the scale of ambition is staggering. A sample of mission statements from our space-tech startups includes a desire to build a ‘health monitor for the planet’, to build the ‘Google Maps for space’, to offer ‘navigation in space as a service’, to establish a ‘fleet of space taxis’, to ‘bring space within everyone’s reach’, and to ‘make spaceflight affordable, reliable and regular’. What’s remarkable is that these are all from young companies, largely set up within the last decade. The opening up of our space sector to private enterprise is a relatively new phenomenon. And it’s not just India that will enjoy the spoils of this liberalisation, but the world at large.

India’s space sector is set to be worth almost $13 billion by 2025. With some estimates suggesting that the global space economy will bring in $1 trillion of revenue in 2025, there is considerable optimism that Indian companies can come to represent a meaningful part of that. So, uh, watch this space.

7️⃣ Snacks🍴

If you grew up in India in the late 80s and 90s, you were familiar with the colloquial notion of imported products, or the feeling of waiting for someone you knew to come back with goodies from abroad so you could get a glimpse into the future. This could mean candy, clothes and snacks from the West, gadgets and electronics from the East - products from countries that were further along their consumerist trajectories. The local consumer goods on offer were mass market products - a consequence of the prevalence of mass media like television and radio as the primary aggregator of eyeballs in India. As a consequence, shelves of corner-shops were usually stocked with commoditised ‘good-enough’ products designed to appeal to a homogenous (and relatively tiny) consumer base.

India at the time was still shaking off its socialist straight-jacket. The economic liberalisation of the early 90s would reset the board. In the ensuing years, policies introduced to encourage private enterprise and foreign investment (and to relax capital controls) would entice multinational brands to gingerly take their first steps to enter (or re-enter) the country.

In one of our earliest Tigerfeathers essays, we wrote about how we’re currently living in the ‘Second Act’ for consumer brands in India. The Internet has fractured the idea of ‘mass’ media into countless micro-segments, with each of us curating our content diets to suit our preferred form and fancy. ‘Micro’ media in turn spawns micro-brands that cater to specific segments, lifestyles and personalities, as opposed to the general population. Glance across the shelves of modern supermarkets, corner stores and e-commerce platforms, and you see a reflection of India’s changing tastes.

You’ll see glossy wrappers on everyday treats that are staples in every Indian household.

You’ll see products you might have thought you’d never see in India.

You’ll find brands for an increasingly savvy consumer base that wants their products to be a reflection of who they are, what they like, and how they spend their time.

The difference today (as opposed to the liberalisation era) is that these homegrown products are infused with the knowledge of world-class brand building borrowed from their global counterparts. You aren’t making a compromise by buying Indian anymore. On every count - packaging, branding, logistics, quality, storytelling, customer service - Indian consumer brands are more than qualified to compete with their ‘imported’ counterparts. In fact, these brands are now flipping the script, turning their attention to overseas markets after fortifying their base on the subcontinent.

In the bargain, internet-native consumer goods (re: Direct-To-Consumer goods) have emerged as one of the star pupils of India’s startup ecosystem. They comprise a $55 billion market size, estimated to grow at 34% CAGR over the next four years. These brands continue to attract VC dollars ($2.1 billion so far) at a high clip because of the massive market opportunity and the propensity to deliver successful exits to investors. As India’s middle class balloons over the next decade, the number of online shoppers is set to cross 425 million in 2027. By 2030 we will have a consumer class of 357 million people below the age of 30.

These individuals are looking to spend their disposable income on world class products that match their Internet-influenced aspirations and lifestyles without compromising on quality. For much of our post-liberalisation history, this translated to a dependence on treasures from abroad. That is no longer the case.

8️⃣ Games🎮

"The most important [ancient Indus] crafts were in the fields of textiles, ceramic manufacturing, stone carving, household artefacts such as razors, bowls, cups, vases and spindles, and the production of jewelry, statuettes, figurines and children's toys, some of which were mechanical in function. This last category of goods is perhaps the most reliable evidence of the sophistication of this society"

- Burjor Avari (India: The Ancient Past) via Harappa.com

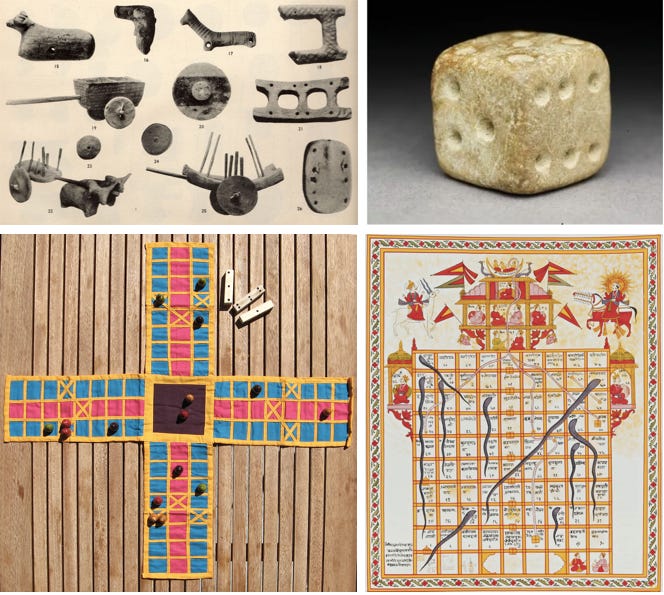

Amidst the treasures coughed up by the ancient sites of the Indus Valley Civilisation (3300-1300 BCE) were trinkets, toys, and counters that volunteered clues about how our ancestors chose to spend their time. Similar to remnants of board games and chess pieces from medieval India, or mythological tales of kingdoms won and lost on the roll of a dice, archaeological evidence suggests that civilised societies in India weren’t ambivalent to having fun in their free time.

On the contrary, these games served as a cultural adhesive. They were a reflection of the prevailing values and world-views. They doubled as teaching tools and entertainment consoles. Games like Shatranj (precursor to Chess) and Chaupar (precursor to several cross-and-circle games like Ludo) were designed to mimic military formations and helped to hone one’s strategic and political instincts. Games like Vaikuntapaali (snakes and ladders) sought to reinforce the notions of vice and virtue. Dice and card games vivified the concepts of risk and probability.

The ubiquitous presence of game boards in royal courtrooms, temple grounds and cave walls suggests that people were highly intentional about the time they devoted to leisure. Once the important stuff like cultivation, irrigation, education, and defence was all figured out, they could optimise for entertainment.

You could make the case that 21st century India is mirroring a similar trajectory. In the 2010s, a decade that coincided with the proliferation of smartphones and cheap data plans, the priority was to bestow certain ‘digital fundamental rights’ on people that were coming online for the first time. This meant giving every Indian citizen a way to exercise their digital identity and make digital payments. It meant people could subsequently use their digital identities to open bank accounts and obtain loans remotely for the first time (In 2009, only 17% of Indian adults possessed a bank account). Our ‘big-ticket’ developmental objectives were geared towards solving for financial inclusion, a goal that had confounded policymakers for basically our entire Independent history.

A decade later the India of the 2020s is unrecognisable from the India of the 2000s. Not only do 1.3 billion people now have a digital identity, but our daily lives now tend to orbit around the planetary sphere of our smartphones. After pressing problems like banking, payments and financial services were first to be tackled by enterprising founders, Indian consumers have demonstrated that they are now open to venturing further upwards on Maslow’s digital hierarchy.

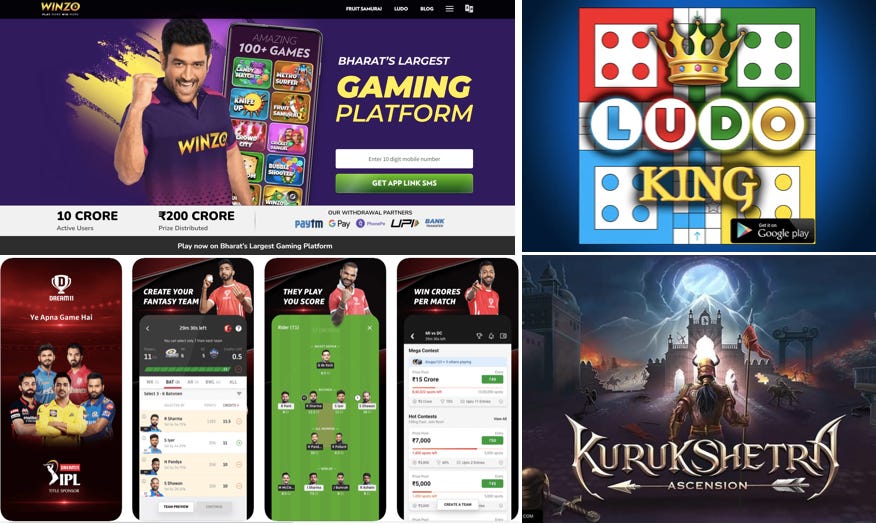

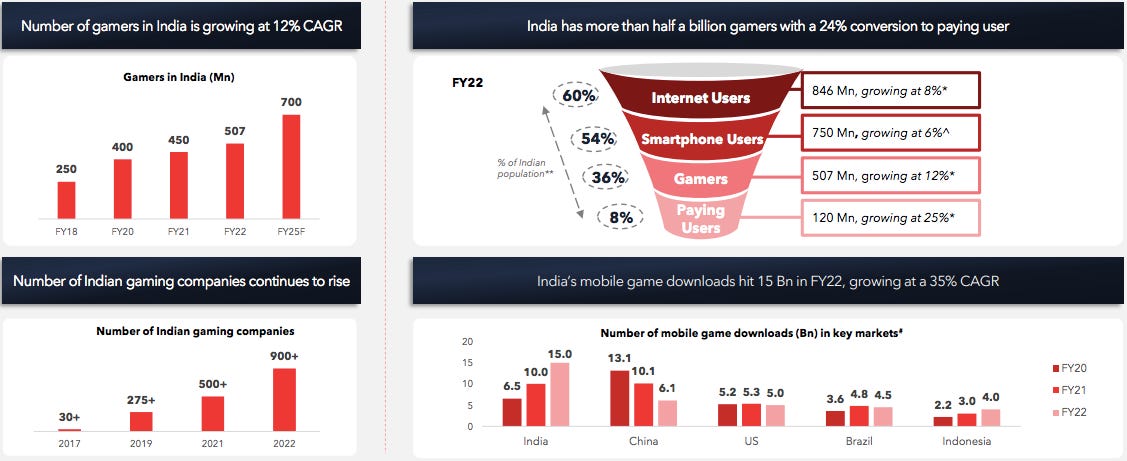

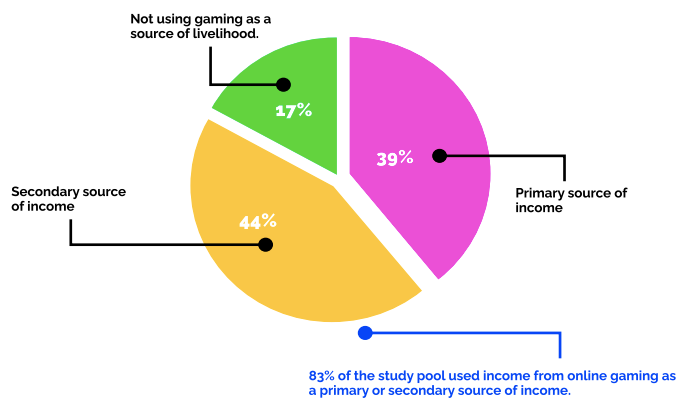

With time and data to spare, people in every corner and from every strata of Indian society have been seduced by the draw of mobile games. Our ancient culture of gaming has found a hospitable abode in the smartphone age. Gaming is often perceived by value-conscious Indian consumers as the content format which returns the maximum entertainment-value-for-time-invested, when compared with other mediums like text, audio, and video. It is perhaps unsurprising then, to note that India’s gaming market hit $2.6 bn in FY22, and is projected to reach $8.6 bn by FY27. We had the highest share of game downloads (17%) compared to any other country last year.

Beyond the eye-catching overall headline numbers (507 million total Indian gamers), what is encouraging for the industry is that 24% (120 million) of these are paying customers. The increase in overall gamer base coupled with a higher conversion to paid users (vs advertising), are compelling reasons for why India is posturing to be a hotbed of global gaming in the coming years.

And Indian gamers are maturing alongside the industry. The ratio of male:female stands at 60:40, almost equally split between metro and non-metro cities. Trends like Web3 gaming, live gaming, ‘real money’ gaming (like rummy, poker etc), and bespoke Indian IP are driving much of the innovation and fundraising in the space. Three Indian gaming companies (Dream11, MPL, Games 24x7) have crossed billion dollar valuations. Another, Nazara, raised $33 mn in a 2021 IPO.

Because of the growing demand for developers, engineers, animators, designers, artists and storytellers, the Indian gaming industry is estimated to create over one lakh direct and indirect jobs by 2022-23 and around two lakh jobs by FY24. Last December the Indian government officially recognised ‘esports’ as part of the "multisports event" category under the Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports. It was a pivotal step towards regulating and regularising gaming in India, priming it for future investment, infrastructure and support at par with established outdoor sports like cricket, football, or basketball.

Gaming isn’t just the pastime of kings and children anymore. It is poised to become a key driver in our entertainment economy. Stay tuned, because Indian gaming is levelling up.

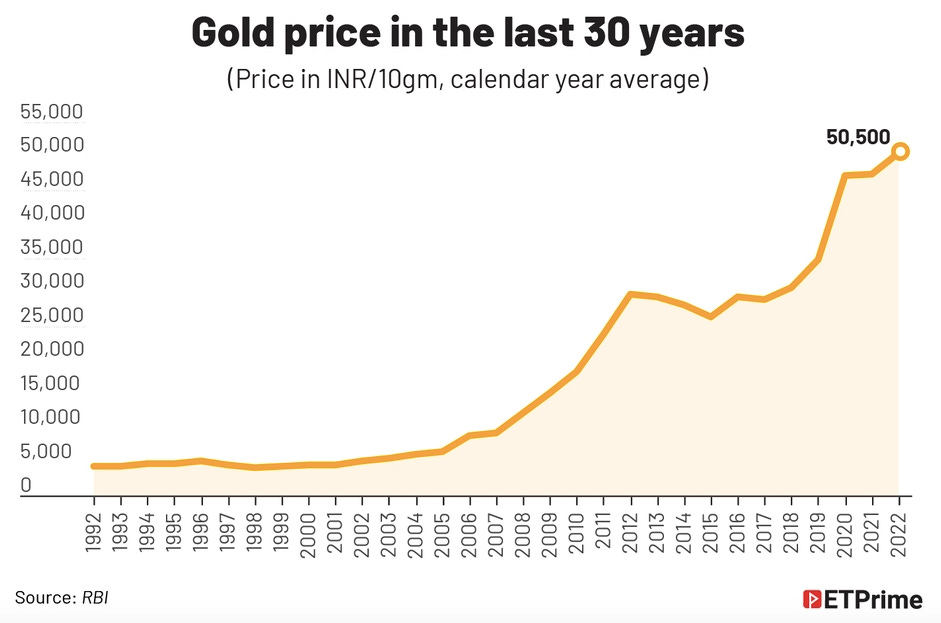

9️⃣ Gold💰

"Gold is the sun of the economic universe, and India basks in its glorious shine."

The tapestry of Indian history is interwoven with gold threads. Our affinity with the yellow metal goes back thousands of years, as far back as the ancient civilisations of Indus Valley (3300-1300 BCE), to the relatively modern empire of the Gupta dynasty (319-467 CE).

Like many of the world’s oldest civilisations (like the Egyptians, Aztecs, Incas, and others) our infatuation with gold has cut across generations and timelines, retaining its potency even as every other aspect of our society receives a modern facelift. In India, gold has embedded itself within religious traditions; it has become entangled with the pomp of wedding ceremonies (10 million of which happen in India every year); it drives the growth of our jewellery industry (the second largest in the world); and it continues to hold an unmatched eminence as a status symbol, a talisman of good fortune, and the ultimate break-glass-in-case-of-emergency asset.

The last point in the paragraph above bears further examination. Throughout Indian history, people from every strata of Indian society have sought it prudent to hoard gold in its various forms - bullion, coins and jewellery. That can be extended even to its ‘financialised’ avatars like bonds and ETFs. It is estimated that Indian households today hold 25000-27000 tonnes of the precious metal (valued at 37-40% of India’s GDP), amounting to 9-11% of the total amount of gold in the world. For good reason.

Gold has historically been seen as the ultimate safe haven asset - both, by households trying to protect their wealth from seizure and inflation, and by governments intent on fortifying their monetary systems against currency collapse. It also serves as a surefire route to accessing credit for both. Judging by the fascination that humans have had with shiny metal over millennia, gold will likely continue to hold a hallowed socioeconomic status as an evergreen economic reserve. But that doesn’t mean it is immune to evolution.

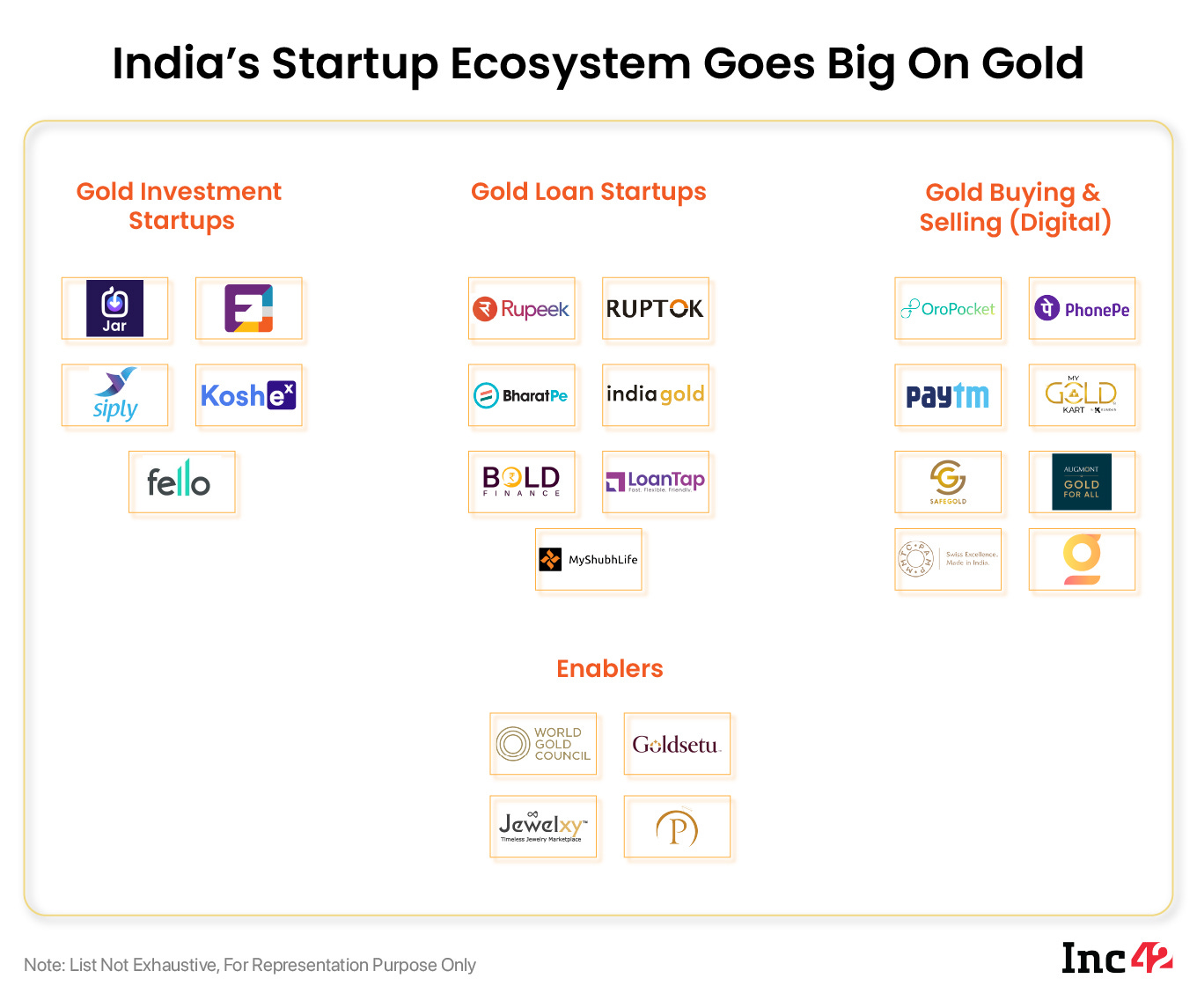

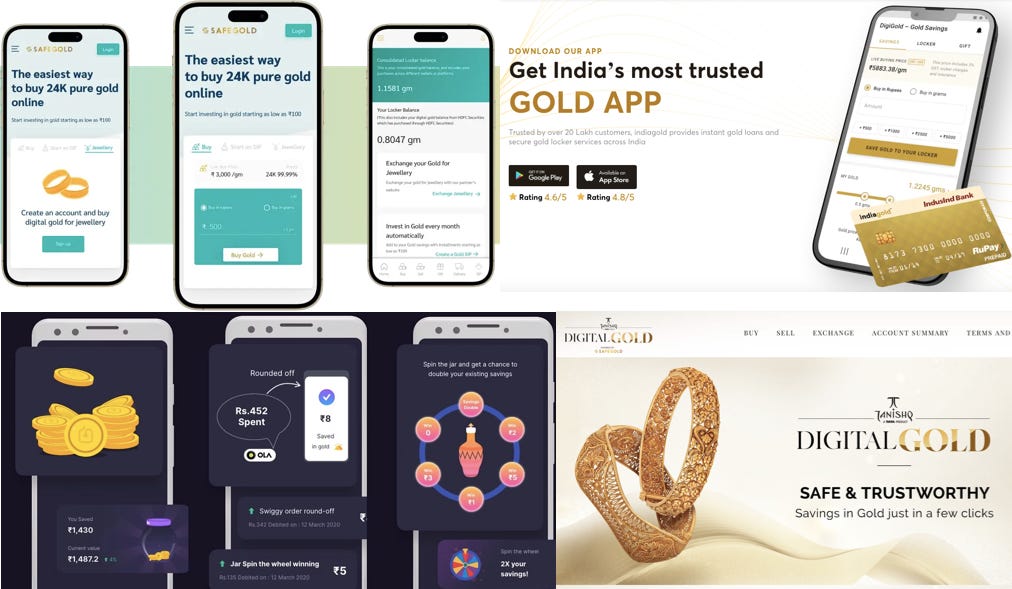

Given the chunky slice of our GDP trapped within the period table, it was only a matter of time before the smartphone forced its way into our gilded supply chains.

The latest chapter in India’s saga with gold has seen a flurry of startups develop slick products to accentuate and augment the process of buying, storing, leveraging and investing in gold. These companies are digitising a practice that has typically been conducted in the shadows (and in cash).

The likes of Jar, SafeGold and Gullak have biltzscaled their way to millions of users by allowing people convert tiny amounts of their savings into digital gold. Rupeek and Indiagold are helping Indians to obtain term loans and lines of credit against their dormant gold holdings. Even traditional jewellery companies like Tanishq (and traditional fintech players like PhonePe and PayTM) have sniffed out the appetite of younger consumers to get exposure to a reliable store of value.

With more than 75% of Indian households owning gold in some form, this continues to be an economic pocket that will see considerable attention and activity regardless of wider macro conditions. As the late Indian economist I.G. Patel once noted - "In prosperity as in the hour of need, the thoughts of most Indians turn to gold."

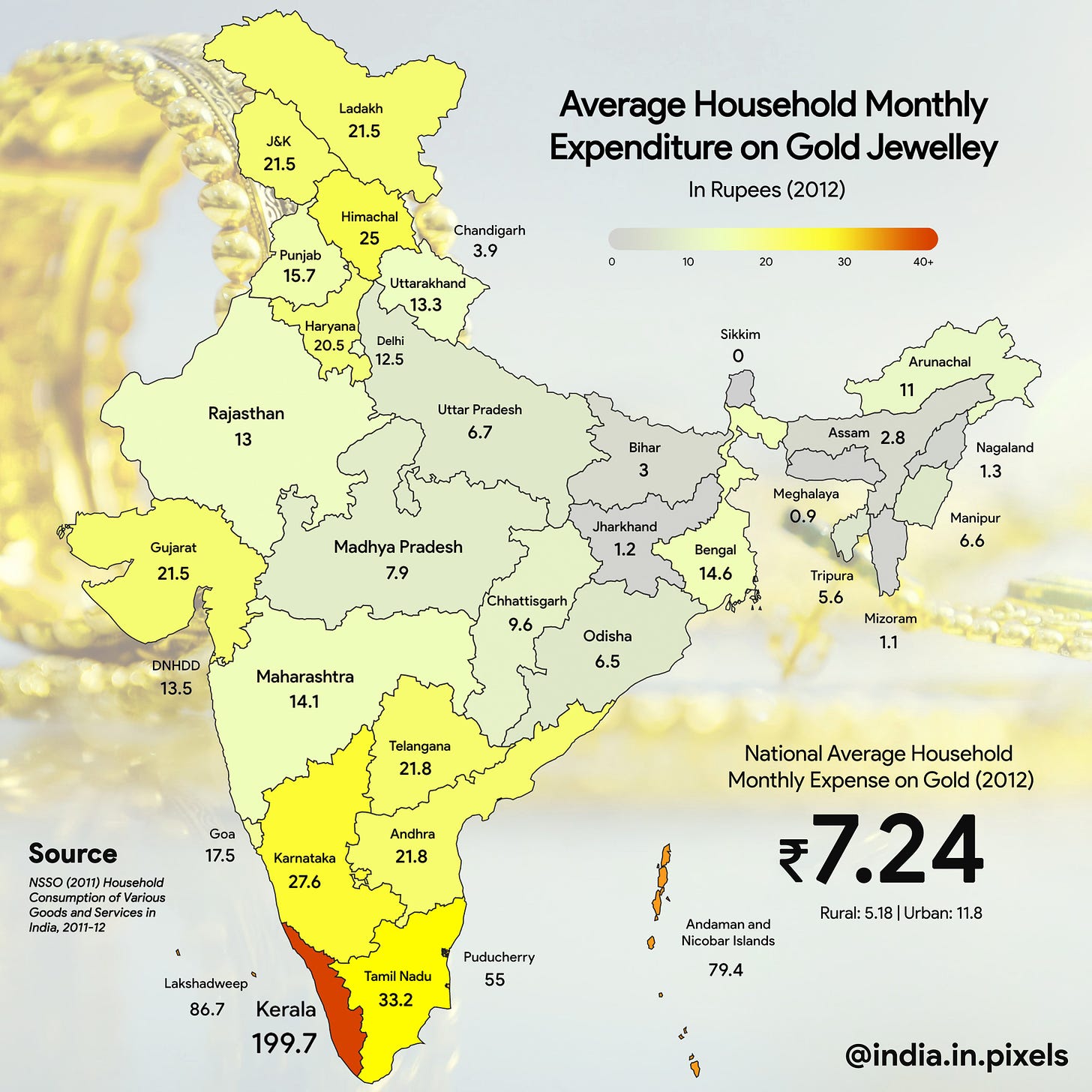

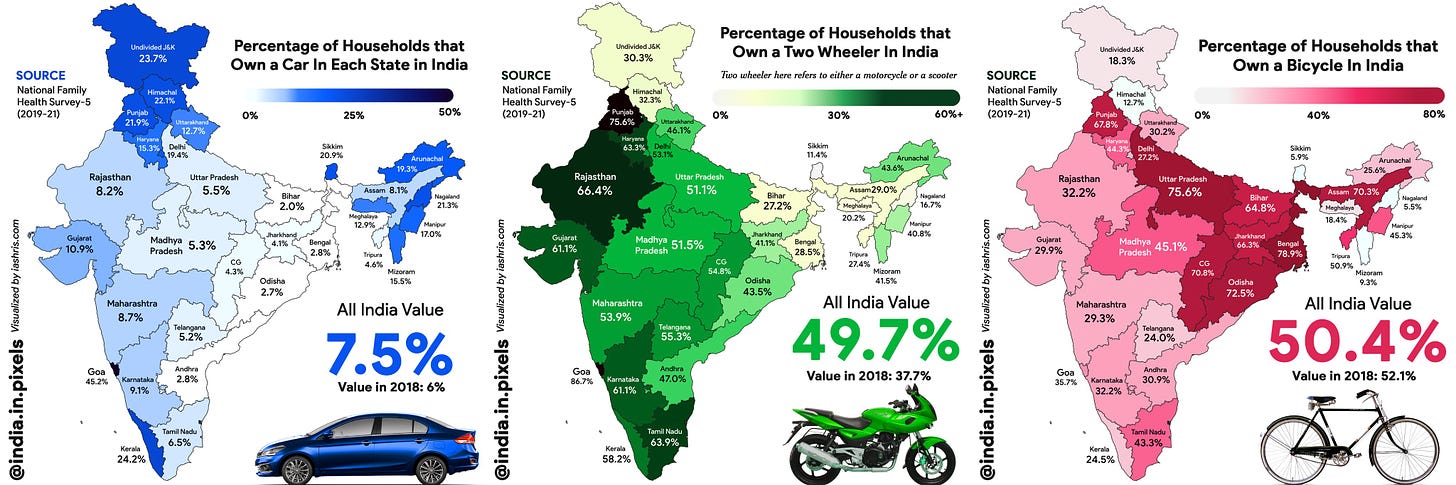

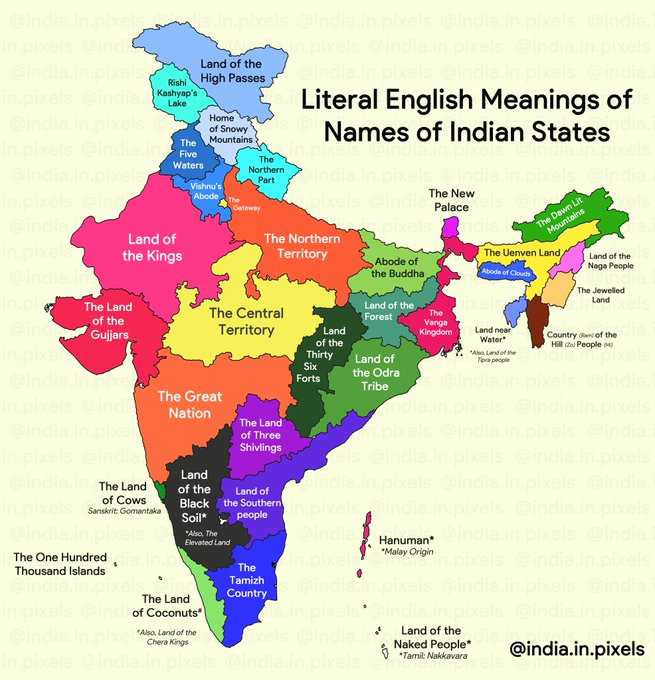

🔟 ‘India In Pixels’🇮🇳

Ok this one is a little different. My goal at the start of this piece was to present a sample of the ‘products that capture how India is changing’. In the absolute literal interpretation of that statement, this list would be incomplete without giving a shoutout to one of my favourite Internet products - India in Pixels.

India in Pixels was originally conceived as a Youtube channel that featured neat videos showcasing data visualisations about different facets of India, across ‘fields like sports, culture, economy, politics and science’. It was started by Ashris Choudhury as a side project after his graduation from IIT Kharagpur in 2019. India in Pixels allowed him marry his interest in design and data, helping to paint colourful caricatures of India in all its many faces. In the years since, he expanded it to a Twitter page that routinely publishes interesting maps of India with data overlaid in his signature style.

This Twitter account now has more than 170K followers (his Youtube page has 406K subscribers). This year, Ashris productised himself. He created a website that gave anyone the ability to make data maps of India in the style of India in Pixels. The democratisation of this tool has sparked an enthusiastic community of Indophiles publishing their own maps of India on Twitter, professing their own creative demonstrations of India in flux.

Like this one about the monthly amount that Indian households spend on gold.

This one about the percentage of Indian households that own cars, motorcycles and bicycles.

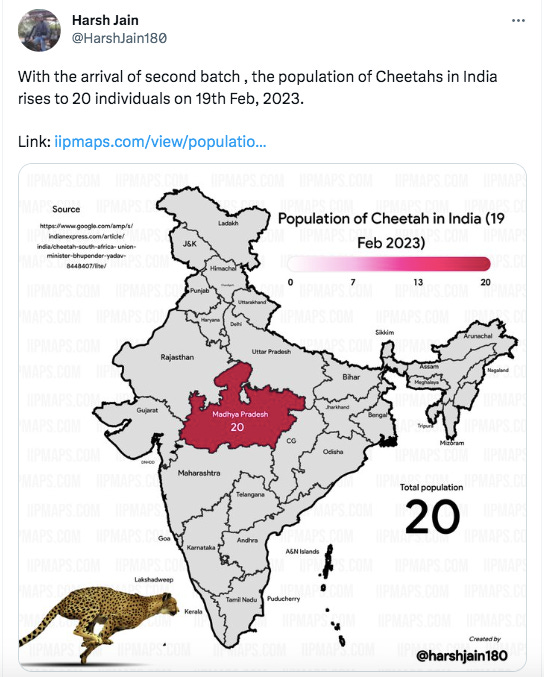

Or this one about the arrival of cheetahs in India.

This one about the English meaning of Indian states.

Or these charts about fertility rates, international airports, railway electrification, or the number of zoos per state. And so on.

His (free) tool is now being used by journalists, media companies, and corporations to visualise data for both private and public facing work. His Twitter account and Youtube page contain some of the best content on understanding India in 2023. Stories like that of Ashris and India in Pixels are the best part about India (and Indians) in the Internet age. A little engineering and a little creativity, all to satisfy the tinkerer’s urge to build something cool.

India is a study in contradictions. The tricky part about forming your opinion based on a chart about India is that, for a country that is so often defined by its statistical vastness, you can probably find the numbers to bend any argument in your favour.

Perhaps less contentious, then, is an appreciation of India’s penchant for invention, and how that has been turbocharged in an era of the Internet, smartphones, and rapid digitisation. We featured 10(ish) themes in this piece (disguised as products), but there’s a near endless supply of companies and objects that would have been great additions to this list. Let us know in the comments if this is a format you enjoy. We’re happy to turn this into a semi-regular series going forward - something like an endless scrapbook on India in the 21st century.

For now, thanks for reading. We’ll see you next time around.

If you made it all the way here and you thought this was a good use of your time, it would mean a lot to us if you took a couple of seconds to share this post.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This is the second essay for which we’ve leaned on the Tigerfeathers community for support. Earlier this month I tweeted out that I was working on this piece and invited suggestions for products that deserved to make this list. I owe a big thank you to @dharmeshba, @karthikiyerks, @thesakshishukla, @PrashantPansare, @iamvarunguru, @TimbreSociety, @bangdesign, @upliance, @RastogiSarthakk, @youngtarun23, @madhavijadhav, @gampala_k, @wizardofid, and @LandeedInc for coming through with suggestions. And to @livingondedge, @AbhilashaPurwar, @zeishahamlani, @fatehsmann, @jaschux and @sssssssssss73 for helping to spread the word. I’m also indebted to Ashris from India in Pixels for taking the time out to chat with me and share his story.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rahul Sanghi most recently served as Fintech Lead for Visa in India & South Asia. He began his career as a consultant with KPMG in London, spending a majority of his time helping the firm set up its global enterprise blockchain and crypto asset advisory practice. He moved back to India in 2018 and joined Koinex (then India’s largest cryptocurrency exchange) as Director of Business and Strategy, before assuming the same role at B2B-SaaS startup FloBiz. He is currently the co-founder of Tigerfeathers, a newsletter (and podcast) that features optimistic and deeply researched stories from the Indian tech ecosystem. He doesn’t know why he’s writing this in third person, but whatever.

![r/dataisbeautiful - Household ownership of consumer goods in India [OC] r/dataisbeautiful - Household ownership of consumer goods in India [OC]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9d37b74e-cae8-45b1-a2bd-42a205595ba4_960x960.jpeg)

Another fantastic read.

Reading each edition of Tigerfeathers evokes a strong feeling a love & optimism for India in me.

Please do more posts like this!

Fantastic read. Also gave me immense validation because you quoted the report I helped build - the Bain report, and the image from that report you've added here is something I had built :)