The Meteoric Rise of Jar, Indian Fintech's Golden Child

In a market fixated on India's richest 10 million consumers, Jar has struck gold by focusing on the other 99%. It's time to talk about what makes them special.

Hello and welcome back to Tigerfeathers, the Internet’s leading source of big cat and bird conservation news deeply researched think pieces about the Indian tech and startup ecosystem.

An especially warm greeting to the 273 new subscribers who’ve joined since our last piece, a repository of 100 brain-nurturing ideas about writing and the creative process. If you’re new here, you should know that we cover things that stimulate us and help us learn about technology, humanity, and… ✨ 🔮 the future ✨ 🔮.

We particularly enjoy covering standout Indian companies that break the mould and reveal to us new insights about entrepreneurship, the world, and ourselves. This article is about one such company - Jar.

And it’s good timing too! You see, there are several reasons why this is a great time to learn about this fascinating company.

Reason #1 - Jar’s recent growth is straight up eye-popping

The company is currently on one of the most incredible growth journeys we have seen from an Indian startup. They recently grew their revenue by an insane 16x in just 12 months. And it’s not like they were starting from a minuscule base either…

If we had to bet, we would wager that Jar will soon be a poster child of Indian tech. So what better time to hear their story and understand their business model?

Reason #2 - Gold is in the news, and hopefully in your portfolios too

As the enigmatic title picture of this piece suggests, Jar’s business is related to the yellow precious metal the Ancient Romans called aurum.

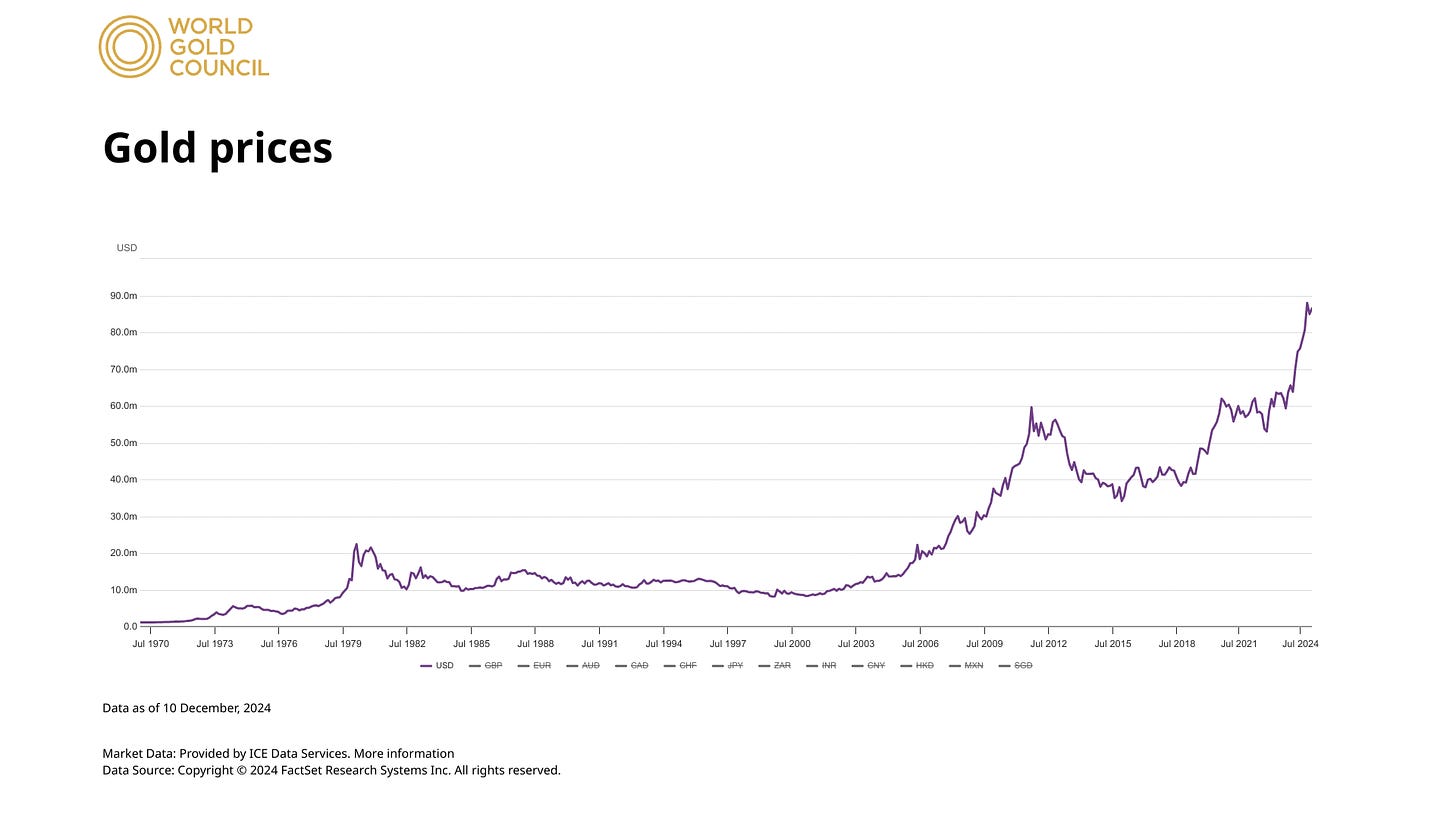

And good old aurum is having its own moment right now. Global inflation, macroeconomic uncertainty, and geopolitical volatility are all potential factors behind its steady upward price action.

But one thing is for sure - gold prices this year are at all time highs, and so is global interest in this beloved shiny rock. Jar’s story sheds light on why Indians, in particular, appreciate this asset, and just how big the market for it is.

Reason #3 - Jar’s story teaches us a lot about India, and about entrepreneurship

Like Sri Mandir, another startup we have covered in this newsletter, Jar is a company that is uniquely Indian in its DNA.

Its success draws upon several interesting stratagems from Indian corporate history, but it also disproves some prevalent notions about how not to construct a big business in the Indian fintech arena.

All said and done, it is difficult to imagine this company being built anywhere else, and that makes it a useful prism through which to study India.

Reason #4 - The existing coverage of this company fails to explain their story adequately

A lot of the reporting in the Indian media completely misses the point about Jar. Articles like the ones below focus on all the least interesting things about the business and omit all the most exciting things. They also contain a surprising amount of factual errors.

But don’t worry, we’ll fix that.

Now, like many good teams, the folks at Jar prefer to keep their heads down and let their work do the talking. They are not interested in PR, and will almost certainly be upset with me for even including these images in this essay.

But I can’t help myself; if I think that many people are misinformed about an important topic, it seems like a worthy challenge to try and disabuse them.

Reason #5 - I’ve been teasing this piece for about 4 years

Eagle-eyed readers of this newsletter will know that I’ve been name-dropping Jar in multiple Tigerfeathers pieces over the last four years.

Whether in reference to the fact that they are one of the leading consumers of UPI’s Autopay recurring payments feature or one of the several startups redefining the wealth-tech industry, Jar has had fleeting mentions in our articles before.

But now, it’s time to put them front and centre.

What a surprise, you’re talking about one of your portfolio companies again 🙄 But OK, you’ve convinced us - let’s talk about Jar.

Fantastic, I’m glad you’re with me. Let’s jump into the Jar story…

…but first, a word from our sponsors. (also a portfolio company 😸)

This edition of Tigerfeathers is presented in partnership with… Finarkein Analytics.

Finarkein Analytics, backed by Nexus Venture Partners, has emerged as a leading player in India's open finance and DPI ecosystem. They are quickly becoming the default data pipe of choice for entities serious about the Account Aggregator space (read our breakdown of this incredibly exciting industry here). Trusted and used by some of the largest banks and NBFCs, they know how to offer scale, speed, and reliability. Any business looking at the Account Aggregator framework as a mission critical piece of their workflows should absolutely talk to Finarkein. Check them out on their website or just drop a mail to hello@finarkein.com. Their customers swear by their offerings being a notch above the rest.

P.S: In case you do reach out, be sure to use the code TIGERFEATHERS. You probably won't get a discount, but no harm trying?

Alright, cut to the chase already - what exactly is Jar?

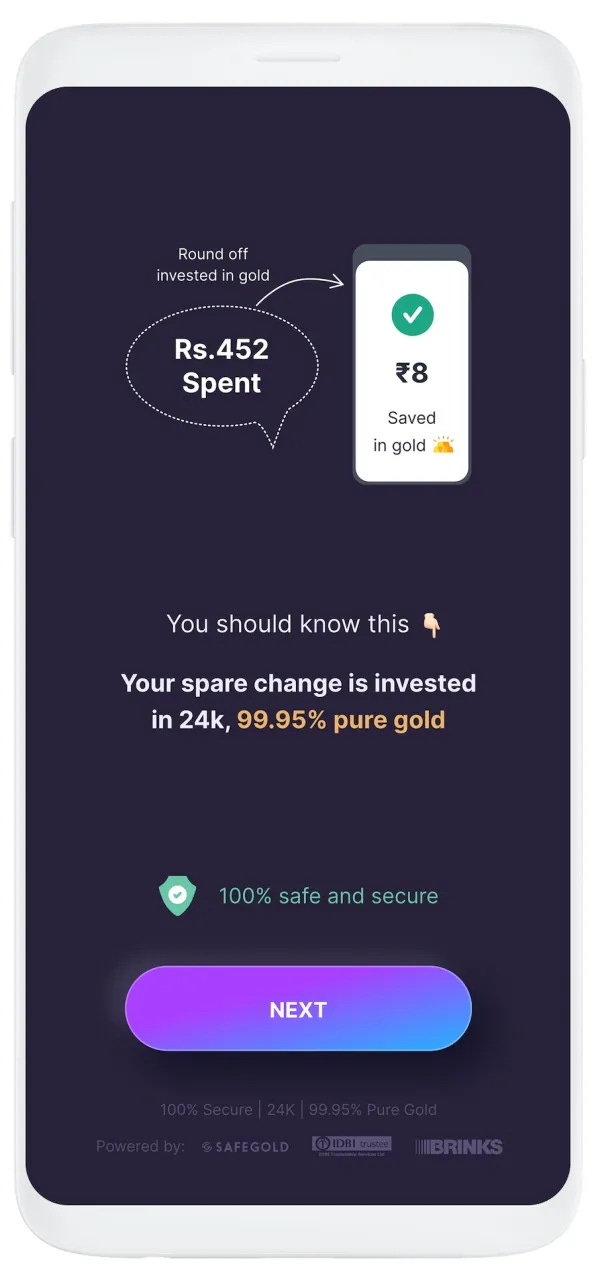

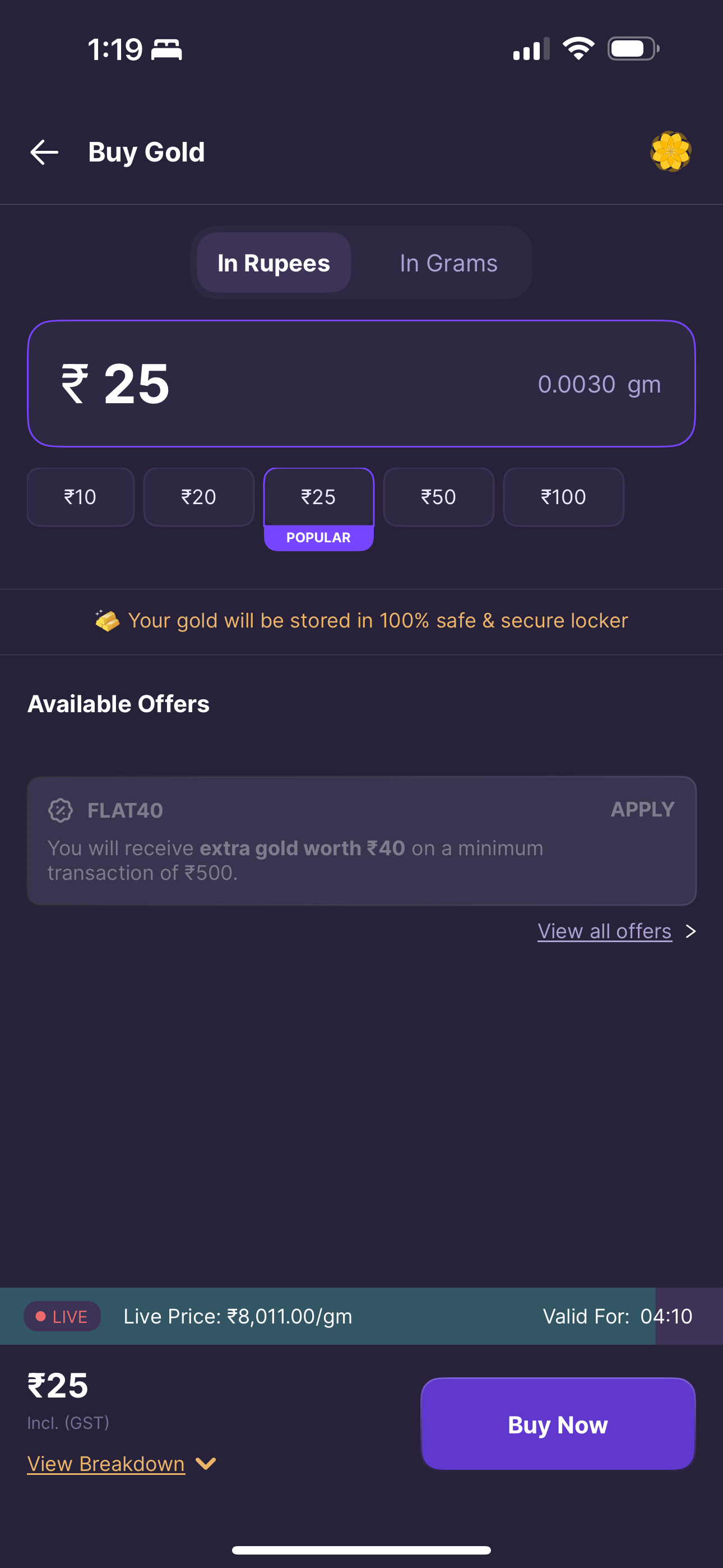

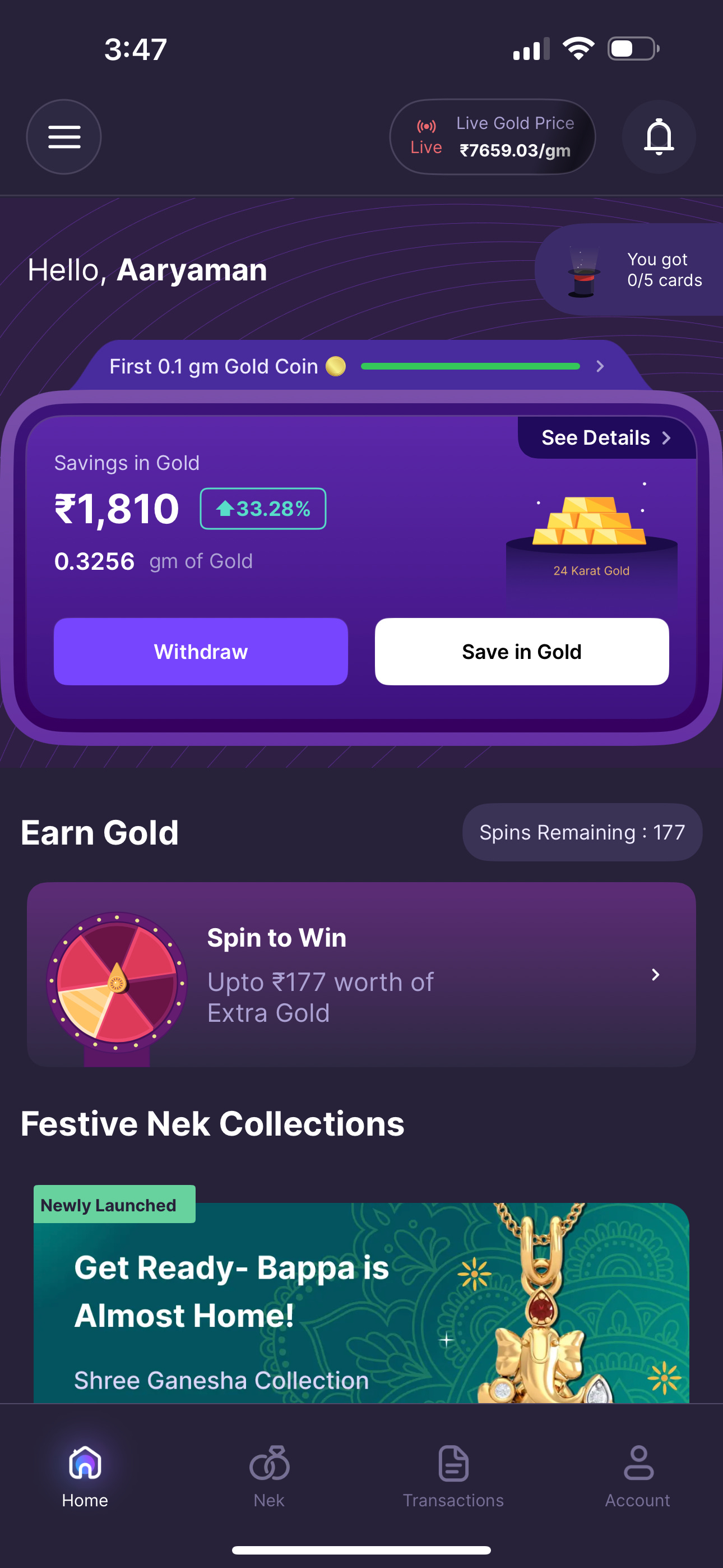

Jar is a mobile app which has one salient feature: it allows people to buy gold.

This can be done as a one-time purchase on a whim, a planned purchase to coincide with culturally relevant gold-buying days, or preferably as a recurring UPI mandate to automatically buy gold at a daily or weekly frequency.

Er… are you talking about like physical gold?

No.

Well, kind of.

Jar users buy something called digital gold, which is the same thing as 24 karat (the highest purity) physical gold, except that it exists in the user’s account digitally, with the physical counterpart held in someone else’s custody.

Why would anybody do that instead of buying physical gold?

Because selling physical gold comes with certain operational and economic limitations. It’s not feasible to package or sell physical gold worth 50 rupees, 217 rupees, or any other small or odd denomination. One can seldom find gold coins or bars weighing less than one gram, and at current prices, one of those would set you back at least 8000 rupees (~$100 dollars).

Furthermore, transporting, displaying, and retailing gold is logistically challenging. You can’t sell gold in a store at say 2:00am, for example.

On the other hand, digital gold can be bought and sold around the clock, and purchases get reflected in the buyer’s account instantly. And most crucially, digital gold can be bought in increments as small as ten rupees.

And this is the crux of Jar’s innovation.

What do you mean?

Although the idea of digital gold has been around for some time (no, this has nothing to do with Bitcoin), nobody had ever marketed it to Indian consumers in such tiny denominations before Jar did.

And although that sounds like a very simple premise, it actually has profound implications and reflects a deep understanding of Indian business history.

Why is that?

Because in India, there is a long tradition of building big businesses by selling things in small units. Time for a quick story.

Back in the 1970s, India was still a planned economy - manufacturers had to obtain permissions or licences from the government in order to produce anything.

Despite this red tape, businesses clamoured to get licensed. The sheer size of the domestic market enticed manufacturers, both from within India and also from abroad.

One of the most alluring opportunities lay in the consumer sector. Although it was a much poorer country back then, India still had millions of eager consumers with disposable income. These folks needed everyday staples such as hair oil and laundry detergent.

Sensing this opportunity, many Indian and international brands had already set up shop in the subcontinent. There was only one problem - the brands were consistently undershooting their sales targets!

Then, one creative entrepreneur in Tamil Nadu came up with a solution. In the balmy port town of Cuddalore, a man named Chinni Krishnan began selling talcum powder and Epsom salts in tiny packets called sachets.

Having studied the purchasing patterns of local consumers, Krishnan had come to the conclusion that many people who actually wanted to buy a product were put off from the transaction due to the large portion sizes and hefty price tags on the goods.

India is one of the most value-conscious economies in the world, and consumers would need a lot of convincing to part with their hard-earned funds. It was simply too much of a commitment to buy a hundred gram bottle of talcum powder for 50 rupees when they didn’t need so much, or when they were yet to be convinced of the product’s quality.

But if those same consumers could buy two grams of powder for 1 rupee, it would give them an accessible way to try the product. They could initially purchase the talcum powder only on days when they needed it, and perhaps graduate to buying larger amounts once they had come to trust the brand and seen the value of the product in their daily lives.

And thus, the concept of selling consumer goods in tiny, cheap sachets was born. Although credit for this innovation is given to Chinni Krishnan, the notable early scalers of this strategy were the Indian FMCG (fast-moving consumer goods) companies like Marico, Nirma, and CavinKares (run by Chinni Krishnan’s son CK Ranganathan).

In the following decade, the major multinational consumer powerhouses like Hindustan Unilever and Nestlé would also jump onto the sachet bandwagon and take it to the next level. The outcome of all this was that FMCG sales skyrocketed, and more and more Indian consumers got the ability to use products that were initially out of reach for them.

So Jar applied the same strategy to selling gold?

Yes, Jar was the first company to sachetize gold by allowing customers to buy digital gold in increments of ten rupees.

And in much the same way that shampoo sachets proved to be a big hit with Indian consumers, Jar’s bite-sized digital gold offerings have also won over the market.

At the time of writing, the company has achieved the following landmarks:

it has over 10 million paying customers

it processes millions of UPI Autopay transactions daily

it handles hundreds of crores of monthly gold deposits (equivalent to tens of millions of dollars)

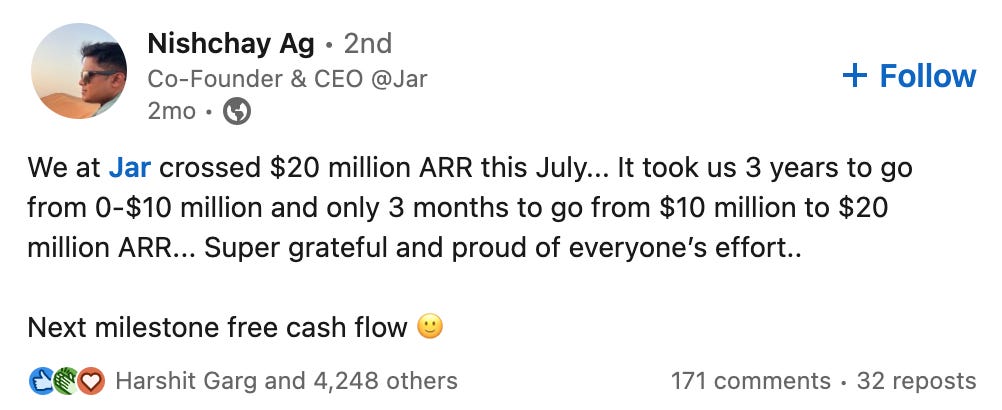

it has a publicly disclosed revenue run rate of $20M as of July (no prizes for guessing that the current run rate is significantly larger)

It’s no exaggeration to say that the company is absolutely flying right now.

Wait a second, how did they get here in the first place?

I’m glad you asked!

Obviously, the company did not just emerge fully formed at a revenue run rate of $20M per year. They actually had very humble beginnings, and their journey is worth studying for any aspiring entrepreneurs out there. So buckle up and prepare for a story.

The year is 2005. In the dry heat of a scorching summer day in Biharsharif, Bihar, a fire sparked to life at a small farm.

Though the flames were quickly doused, they would nonetheless extinguish the hopes of one family - that of Misbah Ashraf. As he watched his grandfather's legacy go up in smoke, young Misbah knew that hard times were coming. The farm had provided crucial income for his family, and losing it was devastating. The blow was made even harder by a bitter discovery: their insurance plan was nonexistent. The 'agent' who collected their premiums had turned out to be a conman.

Without this financial support, the family struggled to stay afloat. Misbah played whatever part he could by selling CDs and tutoring lessons for extra income, even dropping out of college when things got really hard.

One of the most bitter pills for the family to swallow was having to pawn their cherished gold jewellery to loan sharks in order to get liquidity. The pain of losing family heirlooms was heightened by the anxiety of dealing with predatory lenders with usurious interest rates.

Thankfully, the family eventually made it past the hardship, but the entire experience left a profound impact on young Misbah. If only his family had more financial awareness, perhaps they could have avoided all that trouble. If only they had verified the insurance premium receipts, or had built up a larger cache of savings…

The reality is that the financial system is too intimidating for many millions of ordinary Indians. They don’t have the financial literacy needed to navigate complicated products and interfaces that were never designed for them in the first place. When you consider the fact that an estimated 75% of Indian families are just one emergency away from falling into debt and financial insecurity, this makes for especially grim reading.

But Misbah realized it doesn’t always have to be like this. The turning point for him came during Covid. By this time, Misbah had already built, raised capital for, and sold an ecommerce startup called Marsplay. He was now living in Bengaluru, where he had met his future co-founder Nishchay AG.

Hailing from Hassan, Karnataka, Nishchay is an engineer and operations expert who spent time at Honeywell Systems before working at the fast-growing mobility startup Bounce.

Just like Misbah, Nishchay is a gregarious person who is always ready to help others in need. As a result, a lot of young people in his network came to him for financial help when their earnings were destabilized by the pandemic.

This is when the penny finally dropped and the two decided to team up and build Jar. They realized that although there was a huge need for millions of Indians to develop financial literacy and healthier savings habits, there was no product out there that could meet these potential customers halfway. Not a single fintech app spoke to these users in their own (metaphorical but also literal) language and made it easy for them to get started on their financial wellbeing journeys.

And so, in February 2021, Jar was launched with the mission to help Indians develop healthy savings habits by making recurring investments into sachetized instances of digital gold. But while that premise may seem like a winner in hindsight, it was not easy for the founders of Jar to sell their vision at the offset.

You see, many investors at that time were skeptical that Jar’s thesis held up to scrutiny. Was there really high demand for a financial savings product? Why would customers embrace gold as a savings instrument when many other companies had tried and failed to push mutual fund-based products of a similar nature? Were the middle class and working class masses that Jar was targeting savvy enough, numerous enough, and worthy of basing a company on?

All these doubts proved to be insurmountable for many investors - myself included - and Jar was passed up by several prospective financiers. Nonetheless, they did manage to raise a small round of funding from angel investors in March 2021.

Ha! You passed on Jar at their first funding round? You idiot 😂

Yes, I did. In hindsight, it was a foolish decision. But then again, hindsight is 20/20, and I soon had a chance to rectify my mistake.

When Jar eventually launched their app in May 2021, they had electric growth right from the get-go. It turns out that Jar had, in fact, accurately read the pulse of the market. Lots of young people found themselves wishing for a better way to control their spending and build up a savings bank for a rainy day.

Jar tapped into this cohort by handing out fliers about financial health and recruiting students to perform guerilla marketing stunts at their colleges. But this was just a starter - the clincher was that when users eventually got their hands on the product, they were blown away by its simplicity, ease of use, and appealing design.

The word started to spread, and Jar eventually found themselves with a million users just a few months after launch. Around August 2021, they raised another round of capital from Arkam Ventures, Tribe Capital, WEH Ventures, and several illustrious angels (ahem.. such as yours truly).

As the capital poured in, so did the new users. Jar’s product continued to be a huge hit with customers, and the company’s signup numbers achieved liftoff. Their rocketship-like trajectory didn’t go unnoticed, because just a few months after the August 2021 round, Jar raised a large $25M Series A from the aptly-named Rocketship VC and Tiger Global in February 2022.

And the party didn’t stop there. As Jar plowed this new warchest into aggressive marketing, they kept nailing their growth targets. And so the money kept coming in. By August 2022, Jar had raised a further $18M from its existing investors, and in doing so, had ascended to a valuation a full 150 times its valuation from just 15 months prior. As you can imagine, the noise and hype were deafening.

But then, all of a sudden, the music stopped. As global interest rates started to rise and liquidity ceased to flow, the venture capital industry pulled the emergency brake. Startups suddenly found it very hard to raise money, and founders were told to focus on profitability at the cost of growth. It was an austere and difficult time for many companies, and Jar was no exception.

But over the past couple of years, Jar has continued refining their ideas, improving their team, and executing relentlessly on their vision. And now they find themselves here, on the golden escalator - rapidly growing users, revenues, and profitability all at the same time. And that is one of the reasons we’re now talking about Jar.

Wait! That story was cool and all, but you didn’t even really explain the Jar business model! Are they profitable?

Jar makes money in three ways:

margins on digital gold sales

jewellery sales

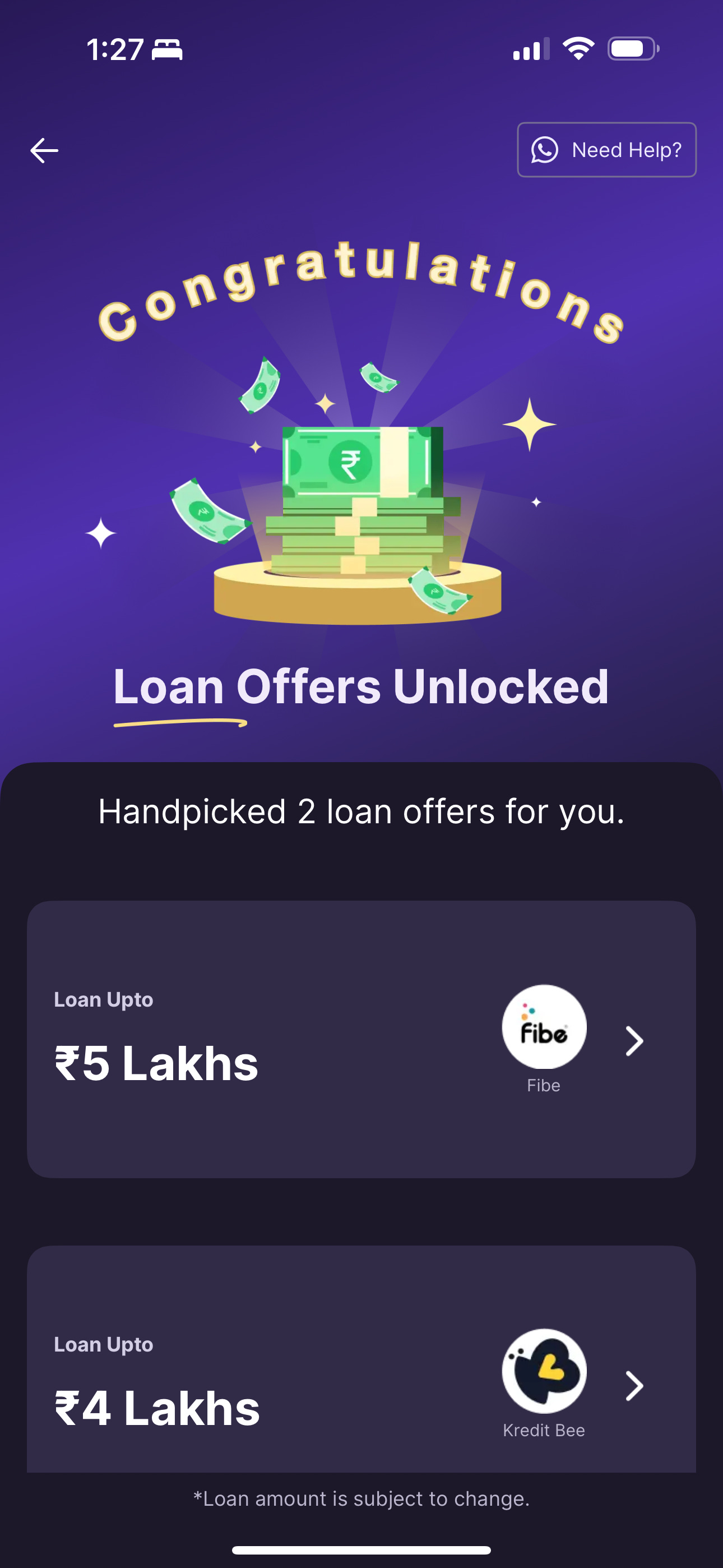

and fees for originating financial products

The bread and butter for the company is digital gold. Their mission statement is to help users develop healthy savings habits, focusing completely on gold as the savings instrument. The business model here for Jar is to keep a small amount of every gold purchase made by a user (but they don’t keep a commission on the sale of gold should a user wish to cash out).

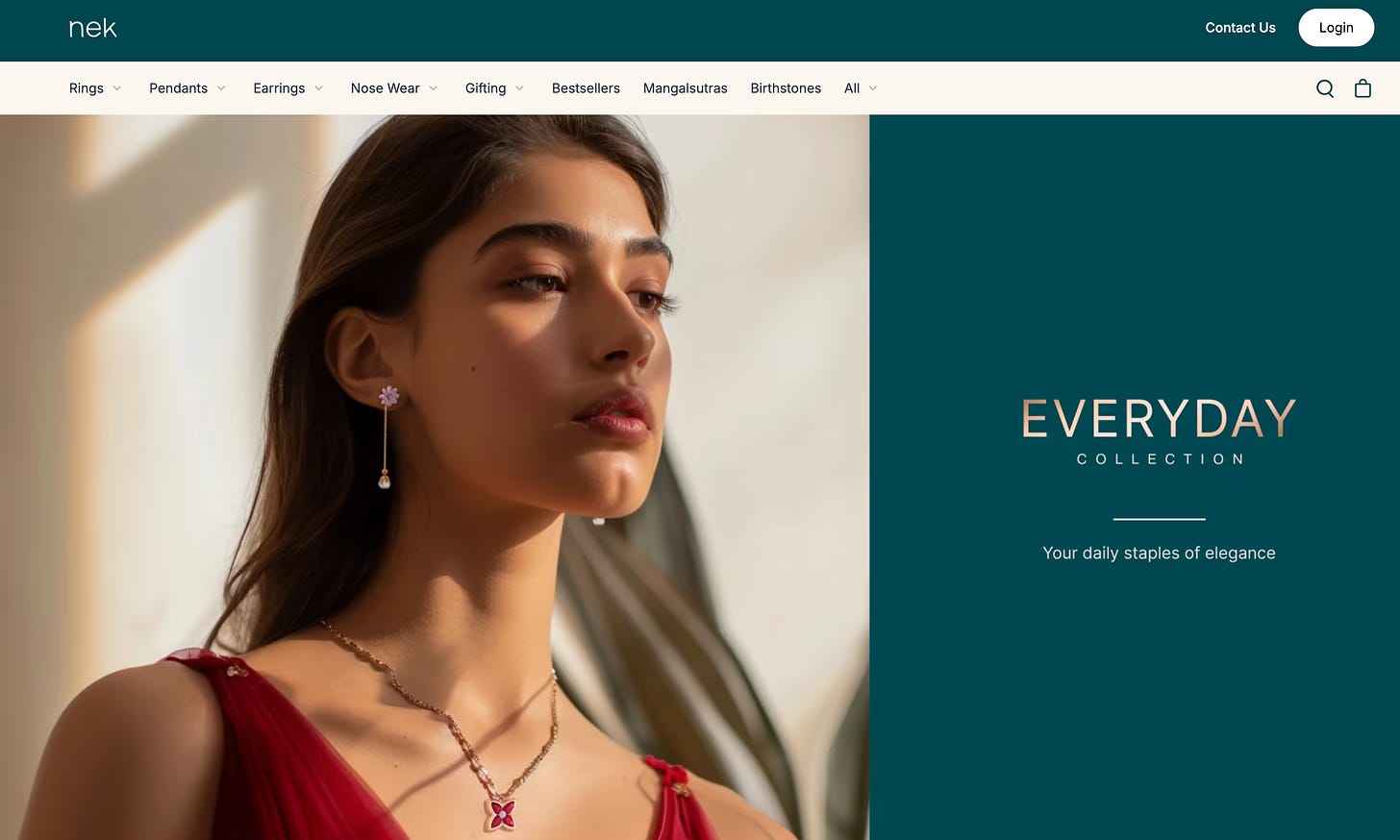

Secondly, Jar also sells gold jewellery. To be more specific, users who hold digital gold with the company can convert their holdings into tangible gold coins, bars, and jewellery designed by Jar’s in-house brand called Nek. For each gold item sold, Jar applies a ‘making charge’ which covers their expenses and leaves them with a profit on top.

Lastly, Jar originates financial products for partner banks and financial institutions. Since Jar has the user’s savings behaviour and gold holdings data, they can help lenders build comfort in a user’s willingness and ability to repay a loan. They can then connect users who wish to take a loan with a willing lender, earning a small fee in the process.

These three streams represent the different ways in which Jar generates revenue. To be even more precise, the company’s revenue figure is made up of margins on gold sales + total sales of jewellery + fees from loan originations. So if Jar has a margin of 2% on the sale of gold, and the company sells 100 units of gold, only 2 units are counted towards revenue. Similarly, if the company earns 1% as a fee for originating a loan, then a loan disbursal of 100 units would result in only 1 unit being counted towards Jar’s revenue.

However, in the case of jewellery, the gross merchandise value of the jewellery is counted as revenue. Consider a user who holds 6000 rupees worth of digital gold with Jar. If that user wishes to convert all his gold into a necklace, he simply needs to pay a making charge of say 600 rupees on top of his existing digital gold holdings. But from Jar’s perspective, they’re selling a necklace worth 6,600, so the revenue figure would increase by the entire amount of Rs. 6,600. I’m just spelling this out because startup accounting can often be murky, but Jar is transparent about how they count revenue.

As for profitability, the company is on the cusp on achieving that milestone. It wouldn’t surprise me if they announce it within a few weeks of the publication of this essay. Given the steady growth they have been experiencing, it’s just a matter of time.

On that topic, what explains their massive revenue growth over recent months? Are they just throwing money at performance marketing?

The short answer is no, they are not just throwing money at performance marketing and digital ads. On the contrary, they have invested a sizeable amount of time and resources into building out their own in-house content team. They have 50 full-time employees who just focus on creating useful, organic content about financial health and literacy.

This content is pushed out through 16 channels - in eleven languages - and via their popular podcast. Every month, these channels get more than 100m views cumulatively. This is a powerful marketing and customer acquisition engine for the company, although in the past they have invested in making viral ad campaigns like this fan-favourite.

The longer answer is that Jar’s recent revenue growth is driven by two commercial strategies: verticalization and horizontalization.

Say what? Speak English, nerd.

OK, let’s talk about verticalization first.

The primary activity taking place at Jar is the purchase of digital gold. When the company first launched its app, Jar only took care of the front-end of buying gold. This means that they were responsible for acquiring users, onboarding them, and making them transact.

On the other end of the operation, Jar used to rely on partners to handle all the nuts and bolts of actually managing the physical gold. After all, if you are selling digital gold to customers, someone has to make sure that there is an equal amount of physical gold lying in reserve should the customer wish to take custody. This logistics-heavy part of the operation is referred to as the ‘gold stack’.

Recently, Jar decided to move away from third parties and launch their own gold stack, which they have dubbed Digigold. This entails much more logistical and financial hassle, but also gives them more visibility and control when it comes to operations. This increases the margin they make on the sale of gold, and also allows them to offer back-end gold stack services to front-end partners of their own.

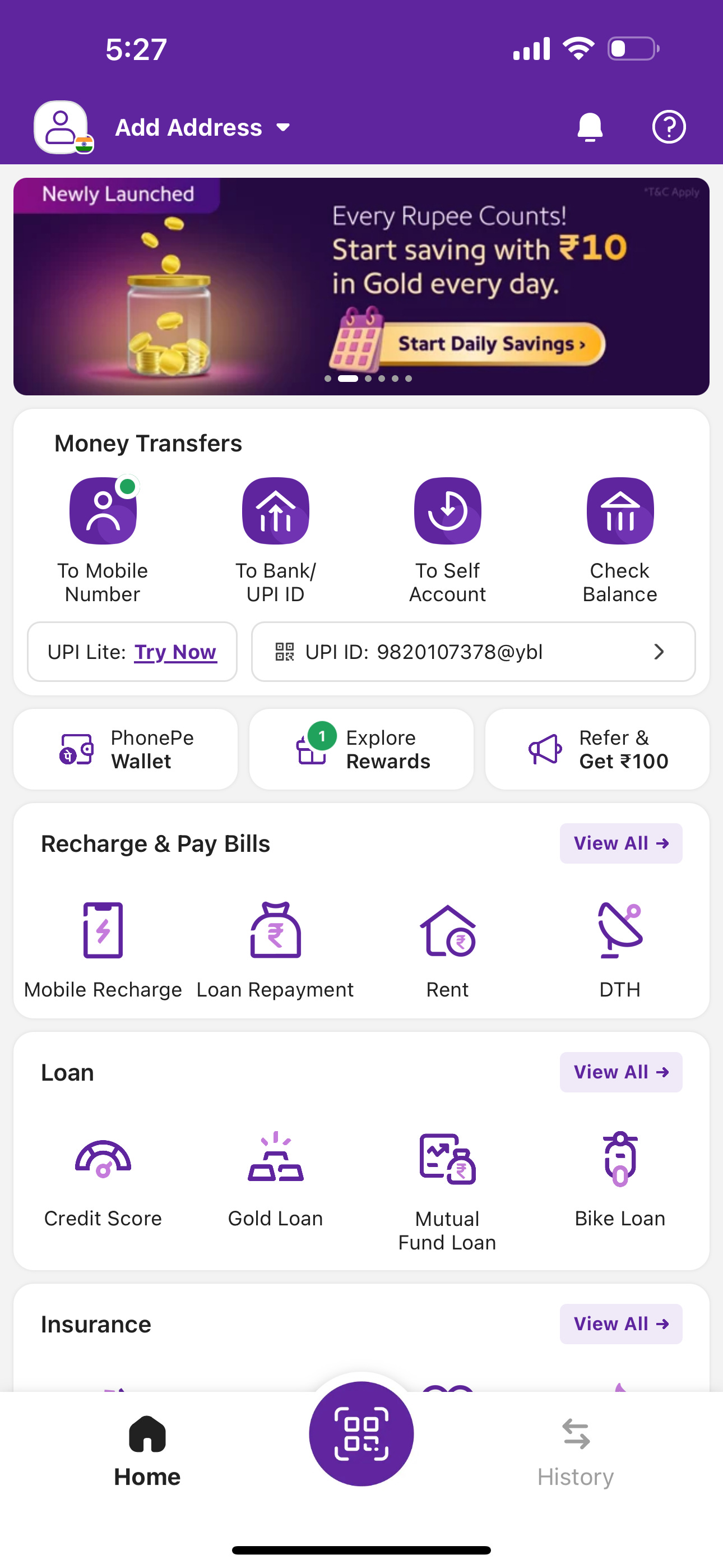

For instance, PhonePe recently went live with a scheme encouraging their 500 million users to set up daily deposits in gold. The back-end of this operation is powered by Jar, who will split the margin with PhonePe.

According to the company, this partnership has already been extremely valuable, and the same template can be repeated with other partners who wish to extend daily gold savings to their users.

This is what we mean by verticalization.

OK, so they’ve basically moved up the gold value chain. Got it. Out of curiosity, what are the additional logistical and financial headaches that come with doing this?

The biggest headaches are procurement and financial reconciliation.

Jar has to go out and buy gold in the wholesale market. Since gold is a regulated commodity which has special tariffs and restrictions over import, only a few licensed trading bodies like MMTC and Riddhi Siddhi are allowed to import it and wholesale in bulk.

Jar has to strike procurement agreements with these firms, but that isn’t as easy as it sounds. First of all, the price of gold constantly changes in response to demand and supply, so buying too much or too little at the wrong time can be costly.

Secondly, the company always has to have enough gold to be able to fulfil customer orders, but not so much gold that they’re sitting on unused inventory. They also have to account for the fact that every day, some users will ‘cash out’ and sell their digital gold back to Jar.

In summary, sophisticated demand and supply forecasting is required. As you would expect, buying larger quantities of gold yields better economies of scale, but also comes with the risk of exposing yourself to the gold price in case it drops.

For this reason, the gold that Jar buys also has to be hedged using financial derivatives, so another layer of cost and complexity comes into play. In effect, Jar has to run a full fledged commodities trading desk just to keep their raw material coming in.

After that, they still need to take control of the physical material and make sure that they’re receiving the correct quantity and quality of gold. Then comes the matter of storing, securing, and auditing the material according to the stipulated standards. They must also maintain the ledgers that map each customer’s digital gold holdings to their physical reserves, and then take care of the delivery of the gold when customers wish to convert it to jewellery or sell it.

So as you can see, it is not a casual undertaking. But the silver lining is that it allows Jar to have more control, and more margin like I said. It also helps them that their payment terms with the wholesale gold dealers allow them to enjoy a negative working capital cycle.

In plain language, if customers buy gold worth 10Cr on Jan 1st, that money hits Jar’s accounts instantly. But Jar itself has a short credit period before they have to actually pay the wholesalers for the gold. So during those few days of negative working capital when Jar has users’ funds with them before paying them to the wholesalers, the interest income accruing from those funds is kept by Jar.

Well, that’s definitely a nice bonus. What about horizontalization?

Horizontalization refers to the addition of new revenue streams, namely the launch of the Nek jewellery brand and the loan origination model.

The sale of jewellery, in particular, has been a huge filip for the company. Although Jar only launched their brand Nek in March 2024, it is already operating at above a 100Cr ($12M) revenue run rate. It actually comprises 40% of the overall corporate revenues, even at such an early juncture!

Moreover, the launch of Nek has also had a knock-on effect on Jar’s digital gold business. Because users can now see on the app an option to convert their distant, intangible digital gold into tangible, useful jewellery that they can wear and store themselves, it drives them to save more frequently and in higher increments.

But even the users who don’t buy jewellery often end up increasing their savings behaviour as time passes. The theory is that as the Jar brand has grown more established and trustworthy, the customers have amped up the quantum of their gold purchases. It’s similar to the talcum powder buyer who initially buys a sachet of powder to try it out but then graduates to buying a full bottle once he sees its value in his daily life!

So yes, all things taken together, this explains the mind boggling 16x revenue growth that has taken place in the last 12 months at Jar. It’s a combination of new users coming in, demand expansion amongst existing users, increased margins on the digital gold product, distribution partnerships leveraging Digigold, and new revenue streams from Nek and loan originations.

That makes sense. But let’s step back for a second - why focus on gold in the first place?

The superficial answer is convenience.

Opening a digital gold account for a user only requires a name and a phone number (at least as long as the holdings remain under Rs. 1 lakh in value). In contrast, setting up a customer with a fixed deposit, stock trading account, or mutual fund depository requires far more regulatory checks and clearances.

Moreover, there is no minimum quantity required for buying digital gold. Against this, fixed deposits and mutual funds have minimums that range from the hundreds to the thousands of rupees. This creates friction which in turn results in high drop-off rates. This was a major stumbling block faced by the many fintech apps that tried to build savings products around mutual funds, stocks, and fixed deposits.

Jar never had this problem. Thanks to the easy sign-up process to get a user started with digital gold, Jar has activation rates of over 50% - meaning over half the users who sign up on the app actually make a monetary transaction. That is a huge number by fintech standards.

But like I said, all of this is just the surface level reason. The real reason that Misbah and Nishchay decided to focus on gold is that Indians LOVE gold. The look of it, the taste of it, the smell of it, the texture… it’s like inside every Indian lives a tiny Goldmember.

Mike Myers-related humour aside, Jar targeted gold because it was a huge market with proven customer demand and a high degree of familiarity. Indian consumers might be unversed with some product categories, but gold is not one of them. They know what it is, they understand it, and unlike other financial products, they do not need to be educated about its benefits. They are already obsessed with it and buy it every single year.

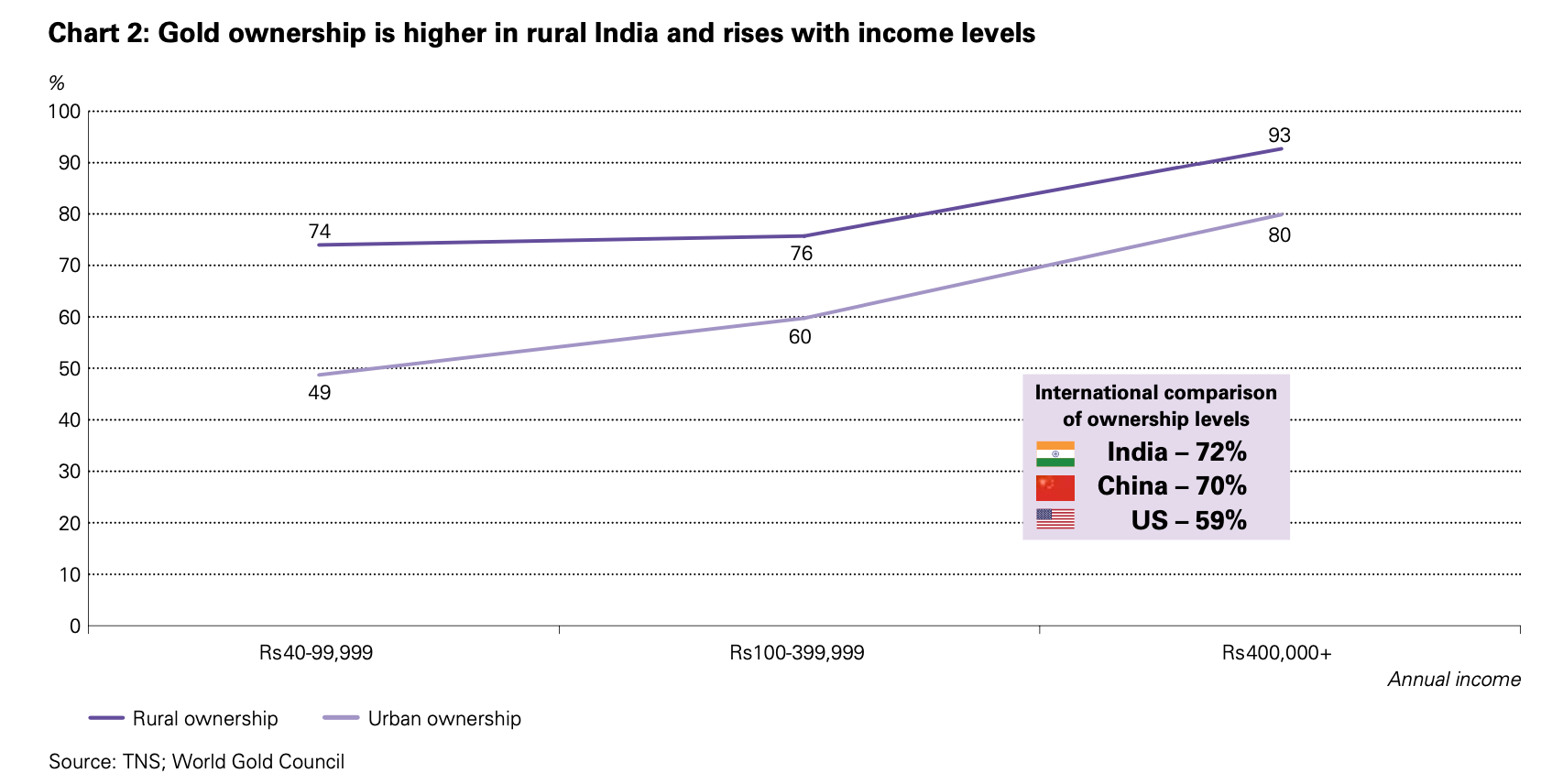

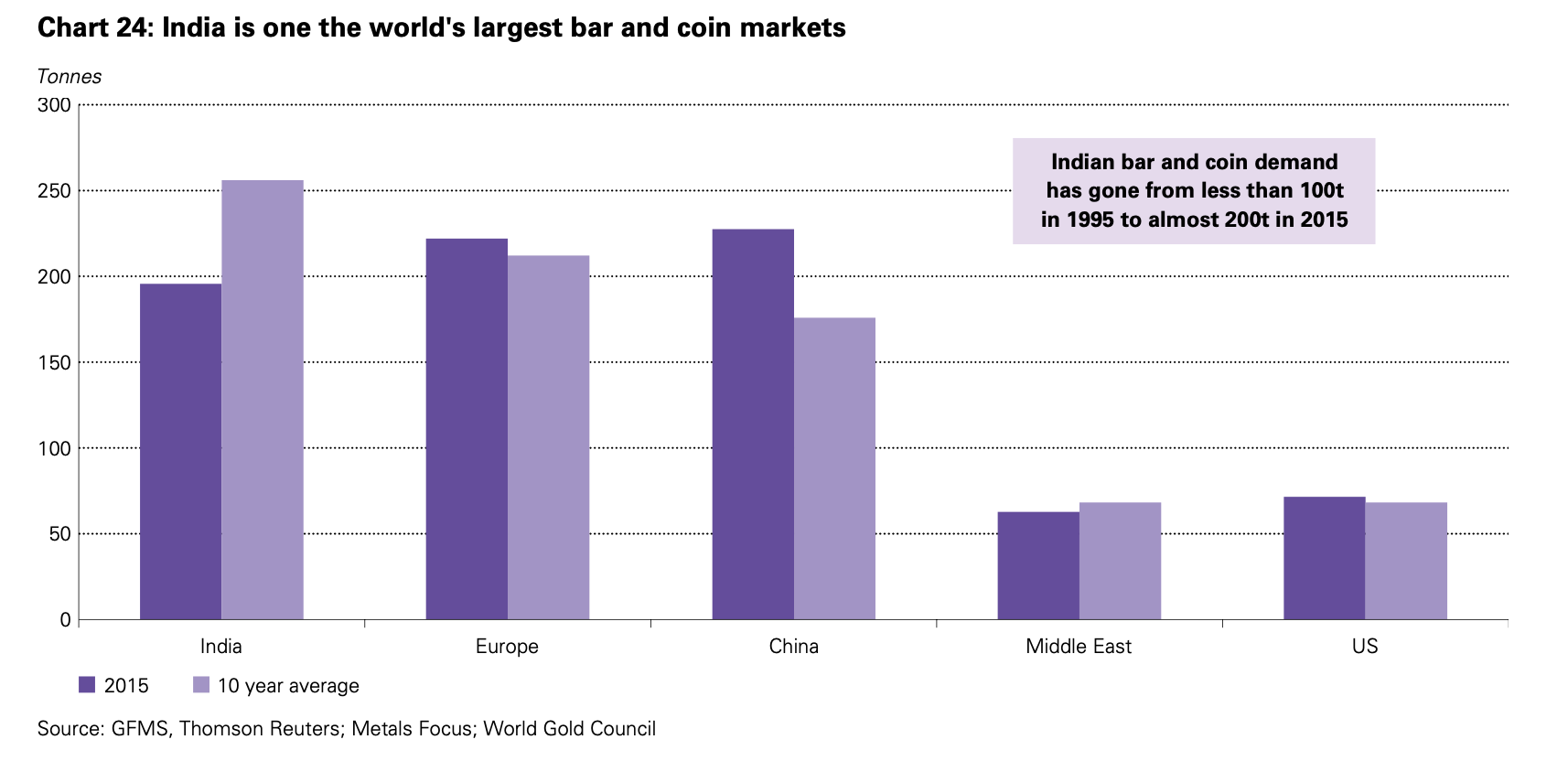

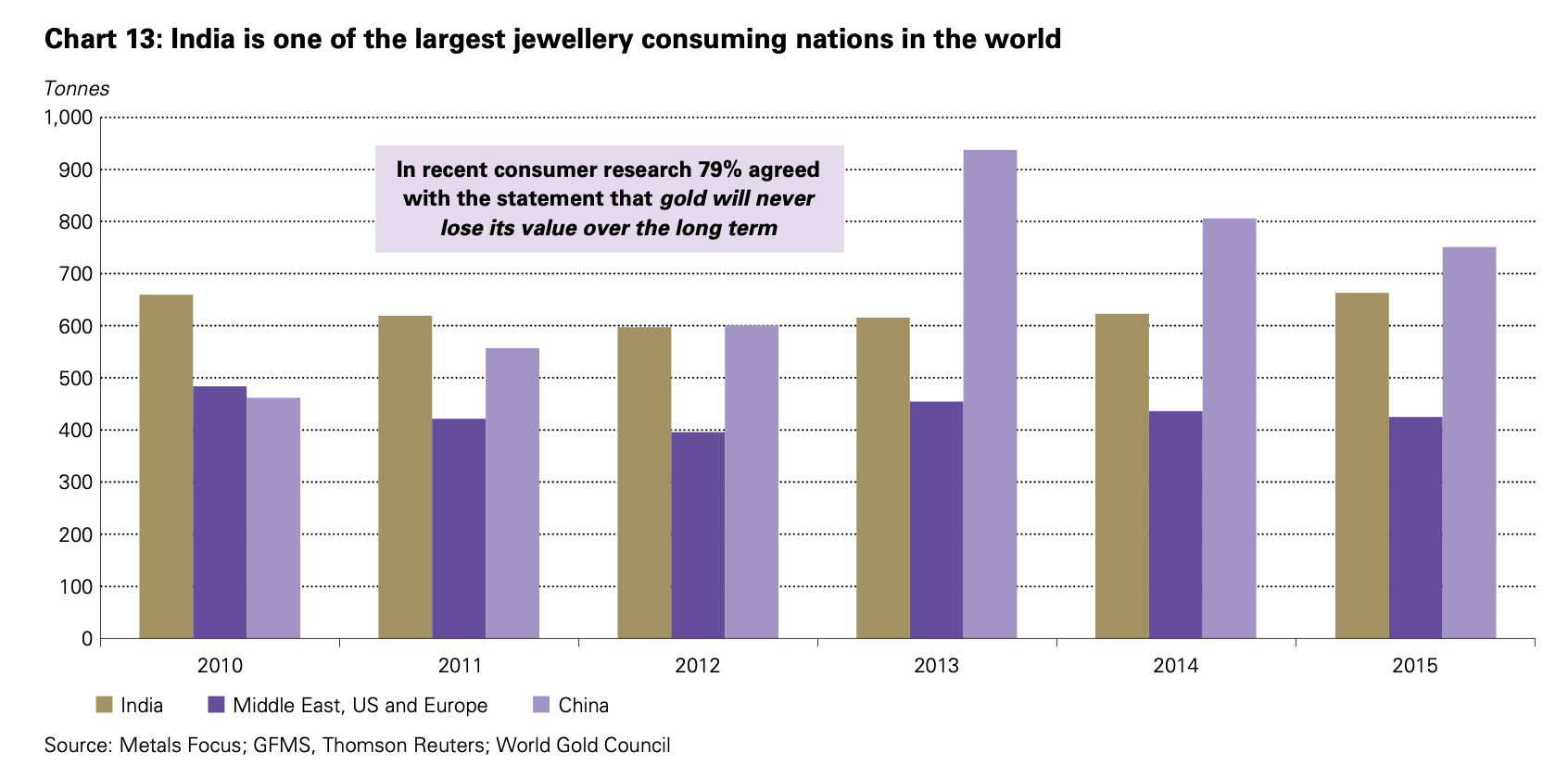

In fact, India is one of the largest markets in the world for gold. We consume more gold coins, bars, and jewellery than pretty much any other country in the world.

In the past financial year, India imported around $45 billion worth of gold, mostly to satisfy the requirements of the jewellery industry, which itself did $80 billion worth of sales in the same period.

And this doesn’t even include the unofficial gold imports to India, which are suspected to add another $10-$15 billion.

What do you mean ‘unofficial gold imports’?

India barely produces any gold. Last year, we mined only 1.7 tonnes of gold, whereas we imported around 900 tonnes.

Consequently, gold weighs heavily on India’s current account deficit and balance of payments considerations. To manage this, the Indian government applies hefty tariffs to gold imports, making it cheaper to buy gold elsewhere than in India.

And this price arbitrage is the motivating factor for gold smugglers and bootleggers, who often come up with inventive ways to bring it into the country. They’ve tried everything from golden baby nappy liners, golden suitcase wheels, and of course the time-honoured tradition of golden capsules in the rectum.

Just last year, rectal transport was believed to be responsible fo-

OK, OK. We get it. Indians love gold and it’s a big market. But why?

My theory as an armchair historian is that the Indian love for gold stems from civilizational memory. In other words, we intuitively understand and accept gold because Indian polities from as far back as 4,000 years ago made extensive use of gold as a store of value and mark of status.

An archaeological excavation in the 1970s found three tonnes of gold (worth around $260M today) buried at a Harappan Civilization site in Gujarat. This unprecedented trove contained coinage, jewellery, and many other gilded baubles. Unfortunately, local villagers looted the site and we lost this incredibly valuable piece of history…

But anywaaaay, the point still stands. Indians love gold, perhaps because it has been a feature of Indian civilization for thousands of years. The same could be said about the Chinese, the other civilization that seems to love gold as much as we do.

To reinforce this theory of civilizational affinity, we can find many more religious and sociological reasons that Indians love gold. The sacred Vedas, which are often believed to have been composed slightly after the time of the Harappan Civilization, make mention of gold ritual offerings. Similarly, the ancient law giver Manu is said to have exhorted worshippers to don golden ornaments when praying.

Nowadays, gold is an inextricable part of Hindu and Indian festivities. We have deities associated with gold, and days earmarked for the purchase of gold coins. In a country as diverse as India, this trend seems to cut across all cultural, geographic, and socioeconomic lines. Whether it’s the Sindhi tradition of gifting gold coins to boys on their coming of age, to the Telugu custom of gifting gold jewellery to the bride on her wedding day, the whole nation treats the honoring of gold as an inviolable tradition.

Lastly, we cannot rule out the visceral and practical experience that modern India has with gold as a store of wealth. During the traumatic partition of 1947, millions of people lost their homes, lands, and businesses as they fled the violence. The only thing they could take with them was their gold. The reliability of the precious metal - even in the face of economic and political upheaval - is something that older generations of Indians have never forgotten.

Point well noted - Indians love gold. So what is Jar’s endgame here? How big can this get?

The Jar team is straightforward about their ambitions: they want to become a large, profitable, publicly-traded business. In the next five years, they aim to process $5B worth of digital gold sales per year. They also want to capture 4-5% of the Indian jewellery market, which is currently estimated to be about $85B and growing at a rate of 6% every year.

Given the large and extremely unorganized nature of the Indian gold and jewellery market (about 65% of the Indian jewellery market is still unorganized), they certainly have the headroom for growth. And if they do hit those numbers, there is no doubt that they will be a massive business,

But growing their bottom line through selling gold isn’t their only objective. They also want Jar to become synonymous with financial security for the middle and working class. This means helping them understand their credit scores, learning about different financial products, and ultimately building a healthy relationship with money. This is important for helping to foster a more secure and ambitious population within the country.

To drive home the point, Misbah speaks passionately about his home state, Bihar. According to Misbah, Bihar produces the most UPSC aspirants in the country - in other words, more people from Bihar attempt the notoriously difficult Indian Civil Services Examination than do people from any other state. Bear in mind, only 0.078% of all aspirants qualify for the civil services, so the people who are applying are ambitious and (hopefully) smart by definition.

But if there are so many smart and ambitious people, why don’t we have more entrepreneurs in the country? Misbah believes it is due to risk-aversion borne from financial insecurity. If only people had more of a financial safety net, they would be able to take the risk of spreading their wings, and the whole nation would benefit as a result.

These are Jar’s ambitious and guiding beliefs.

Lofty, yet commendable ideals. Not to be a cynic, but haven’t we only seen Jar’s journey through a gold bull market? What happens if gold prices fall?

A fair, if slightly misinformed, question.

Gold prices actually did fall some by around 15% from the middle of 2021 to early 2022. During this time, Jar’s users actually ended up buying MORE gold than before. In fact, Jar has never had a day of net selling - when digital gold sales exceed digital gold purchases - in its entire history.

Nishchay and Misbah are adamant that when gold prices increase, the average Jar customer actually becomes dismayed. This is because the customer’s mindset is to accumulate as much gold as possible, not to maximize the value of their investment.

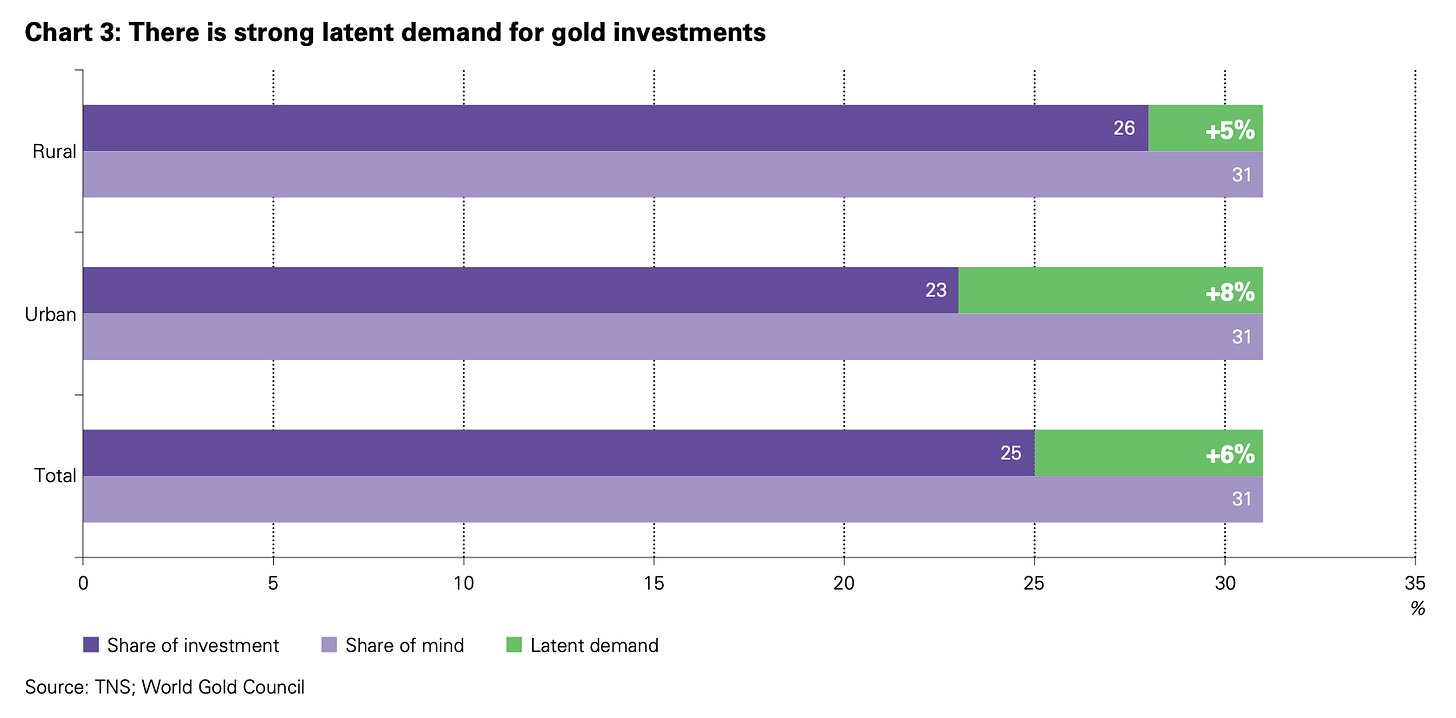

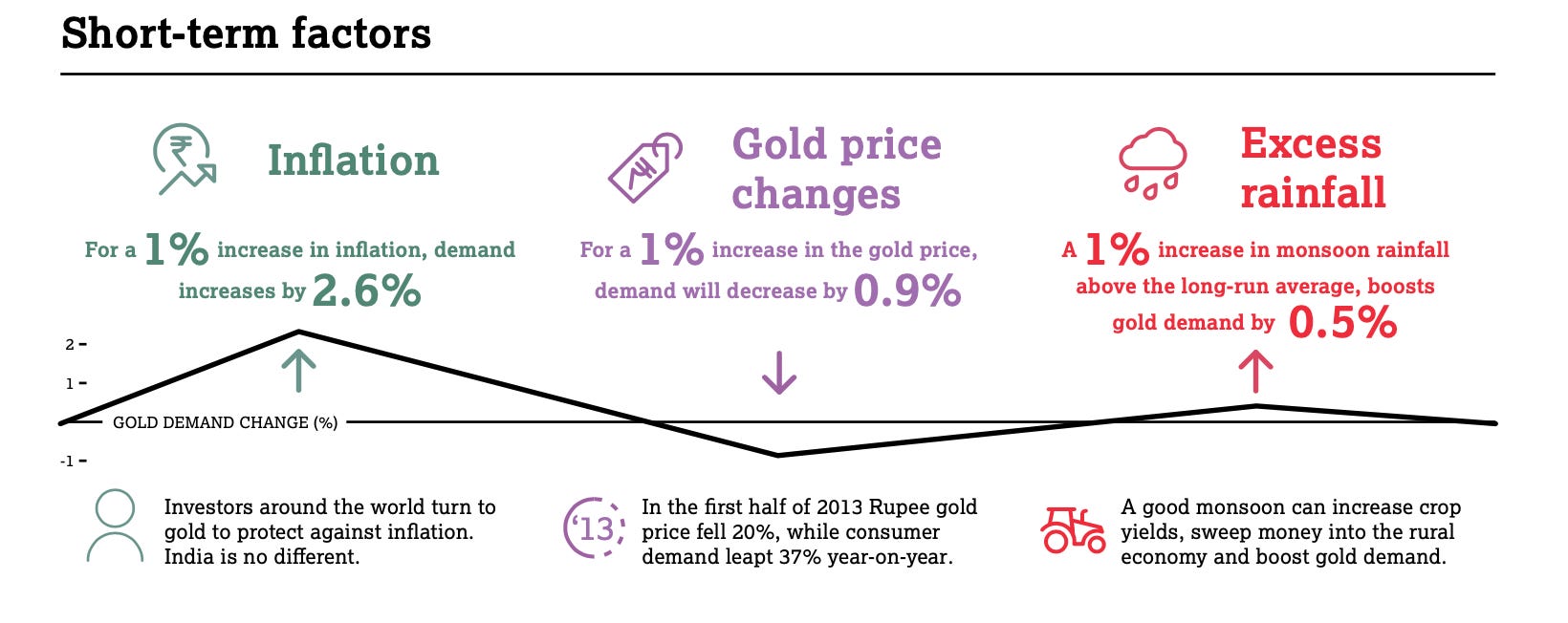

This is why gold holdings are always quoted in denominations of grams, kilos, or tonnes. The people who buy this asset don’t view it purely as an investment. They also see it as an ornament, a status symbol, and something that is worth accruing in and of itself. So a fall in the price is seen as a temporary chance to buy the dip. Data from the World Gold Council (WGC) also supports this view.

This graphic, from the excellent WGC report on India’s gold market, sheds light on the mindset of the Indian gold buyer. They buy more gold when they see inflation, and when they enjoy a good monsoon. But most relevant to our current discussion is the middle graphic. When the gold price rises by 1%, the demand for gold actually decreases by 0.9%. This still results in an increase in gold sold by value, but it means less gold by volume. Which explains why India’s gold demand in 2024 has fallen to a 4-year low of around 700-750 tonnes, down from 761 tonnes last year.

But when the gold price falls, people rush to accumulate more gold. In the first half of 2013, the gold price fell by 20%, but the consumer demand for gold leapt 37% year-on-year for the same period. So Jar should be just fine even if the gold prices come down.

We can’t help but feel like you’re being excessively optimistic and cheerleader-y here. What are the risks here?

Guilty as charged. I am both an optimist and a Jar wellwisher, but I am very happy you asked this question. It’s always important to try and have a balanced view when analyzing products, markets, and companies.

Let’s analyze some potential risks and roadblocks:

Product/execution risk: The chances of Jar’s product failing to catch on or falling out of favour are low, considering the fact that their current users are steadily increasing their savings rates and are also referring their friends. Similarly, the Jar team has proven they can execute on their roadmap with a high degree of velocity, so it seems unlikely that they will suddenly lose the ability to deliver good products and execute at speed.

Supply chain risk: Jar has recently entered the business of handling precious metal, which we now know is not a cakewalk by any means. It is theoretically possible that there could be some thefts or damage to their gold reserves. Similarly, there is also a chance that the gold they procure/ship to customers doesn’t meet the required purity levels for some reason. Incidents like this, however unlikely they may be, remain a risk.

Financial risk: The company does have some exposure to the price of gold, but as mentioned they do hedge their positions. Still, they may find themselves in a cash flow crunch or adverse financial position if they don’t handle their procurement and inventory skilfully. They don’t take any risk sharing when originating loans for lending partners, so this doesn’t add to their liabilities. Notably, they enjoy negative working capital days on the procurement of gold, so that is a huge plus. There is a chance that the funding environment may turn sour again in the future, but this seems farfetched at this moment in time. The company is also close to profitability at a corporate level, so they don’t need funds desperately.

This picture from the board game Risk is just here to make you feel nostalgic for the days when we were kids and the only risk we had to think about was if some audacious mf was gonna try and make a move on your South American territories. Sigh, ok back to adult stuff. Source. PR risk: As a financial app, Jar is in the business of trust. Any incident which impacts their trustworthiness - whether it’s a real incident like the supply chain issues described above or a completely baseless allegation - could hurt their business.

Key man risk: This one feels weird to even talk about, but it is a common risk factor used by institutional investors so I’m including it here. Jar has two founders, but over and above that, it also has a highly mission-driven team comprised of several former founders. The business has clear product-market fit, a simple playbook for growth, and a clear strategy for the future. To top it off, they have an experienced and respected board of directors to guide them should they need it. So I’m going to have to give this risk a low rating.

Market risk: This is not a concern. Jar’s target market is extremely large, with lots of proven demand and established profit pools. There could definitely be margin compression in the digital gold and jewellery segments if competitors arise (more on this in a second), but there is room for several players and the industry doesn’t have a winner-take-all dynamic.

Looking at all these risks, one gets the sense that while Jar definitely has things they must be wary of, they are in a fairly good place as a company. If anything, their largest risk factor still hasn’t been discussed.

Competition?

No. Instead, I’m referring to the two words that make every fintech founder’s mouth go dry: regulatory action.

The financial market regulators in the country - especially the Reserve Bank of India - have been quite… vigorous in how they regulate the fintech sector. And while Jar’s main business lines of selling digital gold and jewellery do not fall under RBI’s jurisdiction, there are still a few regulatory risks the company could face.

For one thing, the customer onboarding and KYC requirements for opening a digital gold account could change. This would take away the smooth and frictionless on-boarding advantage that digital gold has over assets like mutual funds and stocks.

Furthermore, regulation could also impact their ability to earn from their loan origination business. Granted, the concept of originating loans is not currently controversial, but the winds of regulation blow hot and cold on different business practices at different times.

Another noteworthy yet oblique regulatory risk to Jar’s business might come through central government policy. Like we said earlier in this article, the massive amounts of gold that India imports every year really hits us hard in our current account and balance of payments considerations. It’s our second largest import after oil.

The government would absolutely love a way to solve this issue, and to mobilize the 27,000 tonnes of gold lying with the country’s people and religious institutions.

Excuse me, what?!

Yes, you read that right.

Experts estimate that Indian households and temple trusts hold more than 27,000 tonnes of gold. This monstrous stash is currently valued at over $2.3 trillion US dollars.

If my math is correct, that is 31 times more than the gold held by the Reserve Bank of India. In fact, it is more than the amount of gold held by the governments of the top 15 largest gold-owning countries in the world put together, including the USA, China, and India.

🤯 🫨 😱 😮 🙀

And currently, that gold is basically lying in people’s houses and within temple vaults. A lot of it is held in the form of old historical relics that have been accumulating and passed down by various families and kingdoms. In other words, it’s not really doing anything. If we mobilized and financialized this gold, we could simultaneously stop importing so much from abroad and also inject liquidity into our financial system.

And so the government has desperately tried several schemes to entice gold-owners and temples to take one for the team and surrender their gold. The most recent of these is RBI’s Gold Monetisation Scheme of 2015. Under the terms of this scheme, gold-owners can deposit their idle gold with a bank for short, medium, or long term durations.

Depending on the length of the tenure, they can earn up to 2.50% per annum (in rupee terms) on the value of the gold as of the deposit date. At the end of the period, they get back the same quantity of gold that they invested, plus all the accrued compound interest in rupees.

The idea here is that the government and banks would take the customers’ gold items and melt them down to create standardized gold bars. They would then lend these gold bars to jewellers and other buyers of gold, thereby reducing the need to bring in gold from abroad. Just like a normal bank, this concept works great as long as everyone doesn’t ask for all their gold back at the same time.

The only catch is… people don’t want to melt their gold. It often has huge sentimental or historical value, and people simply cannot be bothered to give that up for a measly 2.50% return. Which explains why in the past eight years, out of the 27,000 tonnes of gold lying in this country, the new Gold Monetization Scheme has only managed to accrue a whopping 21 tonnes of deposits.

Anyway, the point I’m trying to emphasize here is that the government may well place further restrictions or tariffs on the possession, import, and trade of gold. Depending on the nature of the policy, this could hurt Jar’s business, but it could also give them new opportunities as well.

Got it, so regulation could upset the apple cart. What about actual competitors?

Jar has a number of direct and indirect competitors.

On the direct side, there is a Y Combinator-backed gold saving platform called Gullak, but they appear to have only between 1 and 2 million signups, according to Google Play.

They could certainly compete with Jar, but their primary differentiator is their gold leasing product. Through this product, a customer can lease their gold to a jeweller in return for some extra return (5% returns on gold is what Gullak advertises).

This is how it works - say a customer has $100 dollars worth of digital gold on their platform. At the same time, a jeweller somewhere in the country needs to buy $100 of gold as part of her raw materials to make jewellery, but her working capital is tied up.

Through the construct of a gold lease, the jeweller can take the $100 of gold that was held by the digital gold platform on behalf of the customer, with a promise to pay it back with interest. This promise is guaranteed by some bank or financial institution, who takes on the risk of the jeweller defaulting.

In this way, the jeweller gets the gold for a relatively low interest rate without straining her working capital, the user gets yield on their digital gold assets, and the bank makes money off the jeweller too (barring defaults, obviously). Lastly, the digital gold platform also pockets a small fee for facilitating the whole transaction.

If this sounds similar to the Gold Monetization Scheme, that’s because it is. Gold leasing is a fairly well known business model that Jar had previously activated, but they shut it down temporarily as they launched their own gold stack. They intend to reactivate it soon, at which point Gullak won’t have a significant differentiator anymore.

Other direct competitors for Jar include the B2B-focused digital gold platforms Safegold and Augmont. The former is a wholesale-focused fullstack digital gold player that aims to provide the back-end services for companies that wish to only run the front-end leg of digital gold sales. In fact, Jar once used their gold stack before launching their own. It is only recently that Safegold launched their retail-facing digital gold applications, and their retail user numbers are between 100K-500K if Google Play downloads paint an accurate picture.

In a similar vein, Augmont is a large integrated gold services company that not only offers a gold stack for swapping digital and physical gold, but also provides gold refining and retailing solutions. Like Safegold, the majority of their business comes from servicing corporate customers - namely jewellers, gold lenders, corporates, and sales agents. They, too, have about 100-500K retail users, going off their Google Play page.

Both businesses seem to be doing well in their own right, but they operate in very different worlds. Jar is a pure B2C company with consumer empathy in their DNA. They are mobile-first, high-tech, and completely focused on scaling as a B2C brand. Both the other companies have significant B2B operations, and its not easy to compete with Jar’s large userbase and brand traction with that sort of split focus.

Moving on, one could also make the argument that super-apps like PhonePe and PayTM may decide compete with Jar. After all, these behemoths already have incredible distribution. How hard could it be to just add a gold stack on the back end and push out their own offering to their hundreds of millions of users?

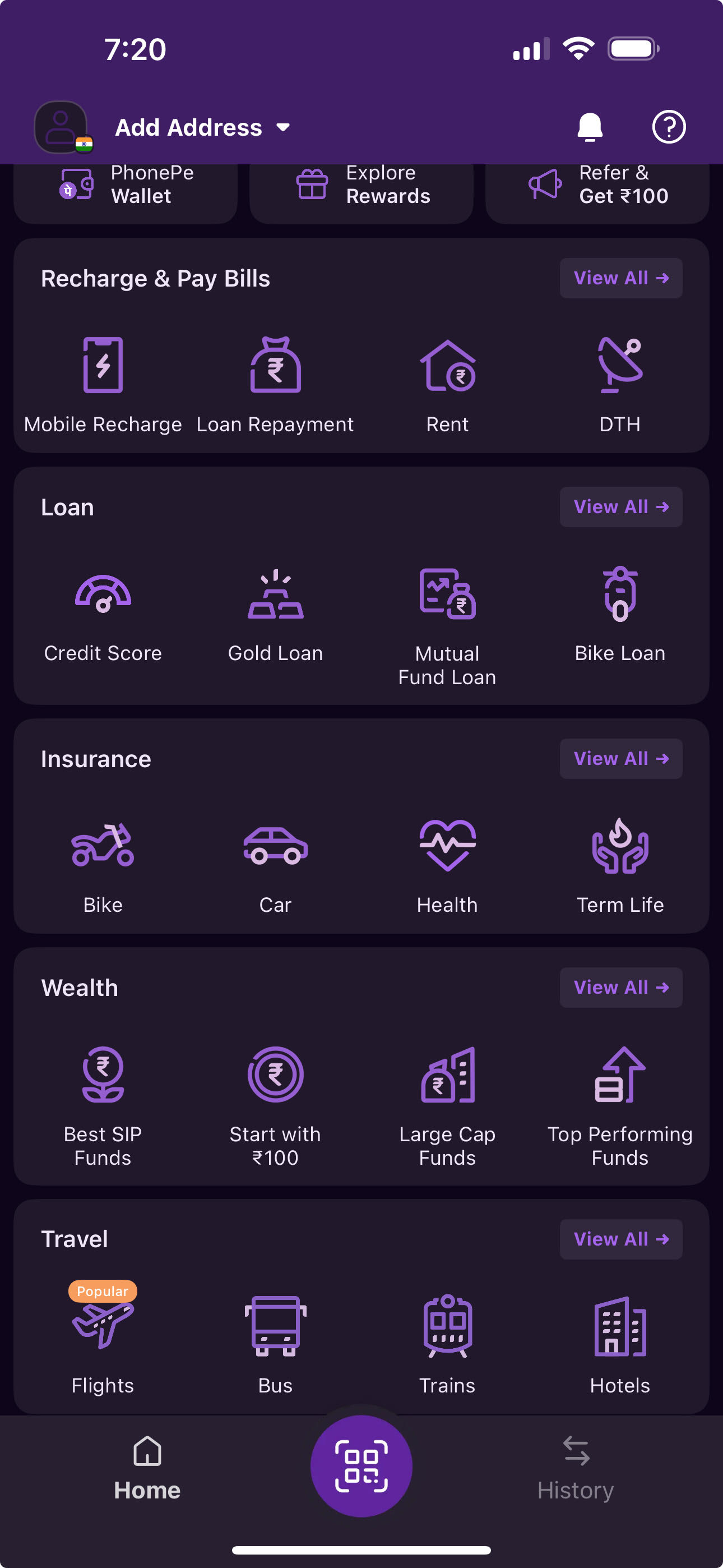

This logic is theoretically sound, and these companies obviously have the technical and operational capabilities to replicate any app out there. But the question is this - is it worth their time? Businesses like PhonePe and PayTM endeavour to become one-stop shops which users can come to multiple times a day to fulfill any of their needs. To achieve this, these super apps are constantly looking for new products to push. To demonstrate, just have a look at PhonePe’s home page.

It’s more crowded than the Gateway of India on a Sunday afternoon. And each of these product categories - ecommerce, hotel bookings, transport, insurance, rent payments - earns revenue for PhonePe. So they will never be able to focus deeply on any of them. They would rather just quickly partner with someone and add gold to the list of a hundred things they offer in their super app. This is exactly why they partnered with Jar to power the back-end of their daily gold savings product.

In terms of indirect competition, you could say that Jar is competing for wallet share with gold-based financial products and completely unrelated financial products.

Starting with unrelated financial products like equities and bonds, there is no doubt that India has very low stock market penetration. As awareness and infrastructure around this asset class grows, more and more working and middle class Indians will inevitably take their first steps towards these products. In fact, we’re already beginning to see a deluge of retail money flow into the stock market. Some of this investment will come at the expense of gold. However, the Indian affinity for gold is something that can probably never be replaced. The data seems to back this up too.

Next, let’s come to gold-based financial products like Sovereign Gold Bonds (SGBs) and Gold-based ETFs. SGBs are a fantastic asset, but they are only available periodically and the minimum ticket size is high. They are not ideal for small investors who want to build up their savings behaviour with sachet-sized offerings.

The same is true of gold ETFs. They’re built for stock market natives who want to keep money in their trading accounts, not for the common man being targeted by Jar. Plus, who is going to push these products? The asset management companies would rather push other mutual funds with higher expense ratios, and online brokers like Zerodha and Groww have far more to gain from pushing lucrative products like futures and options. Gold ETFs are kind of like orphans, which explains why the net flows across all gold ETFs was only $150M in November 2024 in India. I would be surprised if Jar’s monthly net flows into gold did not exceed this number by November 2025.

So that sums it up with regards to competition, but I should probably reiterate the fact that the gold and jewellery markets are not as adversarial as say social media or e-commerce marketplaces. There are no strong network effects or winner-takes-all dynamics here. The opportunity size is gargantuan, and there is ample room for many large companies to thrive.

This makes sense, but it sounds like a VC investment committee meeting. Can you give us some final takeaways to wrap this thing up?

Sure. To help me end this piece on the right note, I’m going to do what I did in my last essay about the technical challenges underpinning India’s Aadhaar database: I’m going to turn to our trusty, if sometimes too serious, AI overlords for a helping hand.

Me: Claude, can you please summarize the main takeaways of this story in a succinct yet elegant manner? Make it good, just don’t make it as good as my own writing. People should know that I’m still a better writer than you are.

Claude: *suppresses a laugh before professionally cracking knuckles*

When I asked Misbah and Nishchay what they hope others learn from Jar's journey, their answer was unequivocal: India's next wave of massive businesses will be built serving the common citizen.

For too long, India's startup ecosystem has been fixated on the top 10% of consumers - what Blume Ventures cleverly dubbed the 'avocado Indians.' These are the cosmopolitan elite who frequent artisanal coffee shops, attend expensive private schools, and eat avocado toast. While this demographic is undeniably valuable, the obsession with serving them has left an ocean of opportunity untapped.

Jar's meteoric rise proves that financial innovation doesn't need to be limited to premium customers. Their success draws from timeless business wisdom: deep customer empathy, relentless focus on execution, and the courage to challenge conventional thinking. A few key principles stand out:

First, success begins with understanding. Before writing a single line of code, Nishchay spent weeks on Bengaluru's streets, interviewing a thousand potential customers. Literally, one thousand people. This exhaustive ground-level research shaped everything from their product design to their marketing strategy. Even today, every member of Jar's product team must speak with at least one customer daily.

Second, leadership means staying connected. Despite their growth, both founders still spend an hour each day speaking to customers. They've even set up a dedicated meeting room where customers - from delivery workers to small business owners - can walk in and speak directly with the team. This constant connection to their users keeps them honest and focused on what matters.

Third, building lasting success means lifting others up. Both Misbah and Nishchay are known throughout India's startup ecosystem as generous mentors and connectors who help people without expecting anything in return. They've built one of the strongest networks in Indian tech not through calculation, but through genuine desire to see others succeed. I often joke that if Misbah started a firm that only invested in founders he's helped get started, Misbah Capital™️ would be the most successful VC fund in the country. This positive-sum mindset has created a virtuous cycle of goodwill that continues to benefit Jar in unexpected ways.

Fourth, talent transcends credentials. Many of Jar's most effective leaders and engineers don't have traditional degrees or resumés. What they do have is resourcefulness, drive, and an entrepreneurial spirit. The company tracks promising individuals for months or even years before bringing them aboard, valuing demonstrated ability over paper qualifications.

Fifth, some of the best business ideas are hidden in history's pages. While Jar's success draws on the proven power of sachetization, they found another powerful template in a century-old innovation from Karnataka. In the 1920s, Manipal's Syndicate Bank launched what they called the "pygmy deposit scheme" - bank agents would visit laborers' homes daily to collect small portions of their wages, helping them build savings over time. The scheme was a remarkable success. Jar has essentially recreated this daily micro-savings approach for the smartphone age, proving that sometimes the most powerful innovations come not from disruption, but from understanding what has always worked and finding new ways to deliver it.

But perhaps Jar's most important lesson is this: India's digital infrastructure has matured to a point where serving the broader market isn't just possible - it's profitable. The combination of UPI, widespread smartphone adoption, and increasing digital literacy has created fertile ground for innovation that serves all Indians, not just the privileged few.

The tired notion that you can't build a profitable business serving the average Indian needs to be put to rest. Jar is proving that when you combine deep cultural understanding with modern technology and relentless execution, you can build a company that creates both financial value and social impact.

In the end, Jar's story is about more than digital gold or fintech innovation. It's about recognizing that India's greatest opportunities lie not in replicating Western business models for elite consumers, but in building uniquely Indian solutions for uniquely Indian challenges. Just as the humble sachet revolutionized consumer goods, bite-sized digital gold might help millions of Indians build better financial futures.

The gold rush, it seems, has only just begun.

Acknowledgements

A huge thank you to Team Jar for spending so much time with me and patiently responding to all my irritating questions and requests spanning several weeks. Aside from Misbah and Nishchay, who probably don’t want to ever hear my voice again, I would like to appreciate the talented Subodh Kolhe and Prashant Singh from the product team. 🍯

I would also like to thank Rahul Chandra and Bala Srinivasa of Arkam Ventures. It was in Bala’s excellent book entitled ‘Winning Middle India: The Story of India’s New Age Entrepreneurs’ that I first learned about the fascinating tale of Chinni Krishnan and his sachets. It’s no surprise then that Arkam Ventures was the first major VC fund to recognize the potential in Jar! 🦇

Penultimately, a huge shoutout to Anushka Rathod. Not only is she a trailblazing content creator who demystifies finance for millions of Indians, she is also a valued Tigerfeathers subscriber. She gave us plenty of insights into the mind of the Indian consumer for this piece, and also informed us that you can now enjoy Tigerfeathers articles on your Kindle device thanks to a product called KTool. So check out her channels and give KTool a spin if you ever want to rest your eyes while feeding your brain 📖

Finally, gracias to my Tigerfeathers partner-in-crime Rahul for his feedback, edits, and encouragement in getting this one over the line. Appreciate, dawg. 🐯🪶

If you’ve made it to the end of this piece, thank you so much for reading 🧡

Iconic piece for an iconic company. What an effort🎩

Loved this piece (also an investor in Jar, as a disclaimer). Knew about Nek but wasn't aware of the backwards integration into the gold stack. Thanks for writing this one!