The Account Aggregator Bible

Everything You Need To Know About India's New Fintech Revolution

Hi there everyone 👋🏽

It’s so good to connect with you all once again, especially the 935 new subscribers who have joined the Tigerfeathers family since our last piece.

There are now over 6500 of us, which means that we’d completely fill up the Royal Albert Hall. Watch out Maracanã, you’re next 🔥🇧🇷📈

Aaryaman, it’s been like eight months since you published anything and now the first thing you do is hit us with a picture of a video game fintech clown? What’s going on mate.

Dear readers, welcome back. I offer my deepest apologies - for the long hiatus, not for the clown art. I shall never apologize for my art, especially when it is necessary to lighten the atmosphere around what has traditionally been a fairly somber subject - fintech infrastructure. But I do regret the extended sabbatical - hopefully this piece makes up for it.

Alright, go on then. What is so pressing that it sprung you out of hibernation?

Just in time for Diwali ‘23, this country has another firecracker on its hands. Another fintech firecracker. It is known as the Account Aggregator (AA) framework, and it is the third prong of India’s technological trident aimed at one of its most abhorrent demons - financial exclusion.

And just like the other two prongs (which we shall hear about imminently), this weapon is blazing a course of incredible adoption and impact.

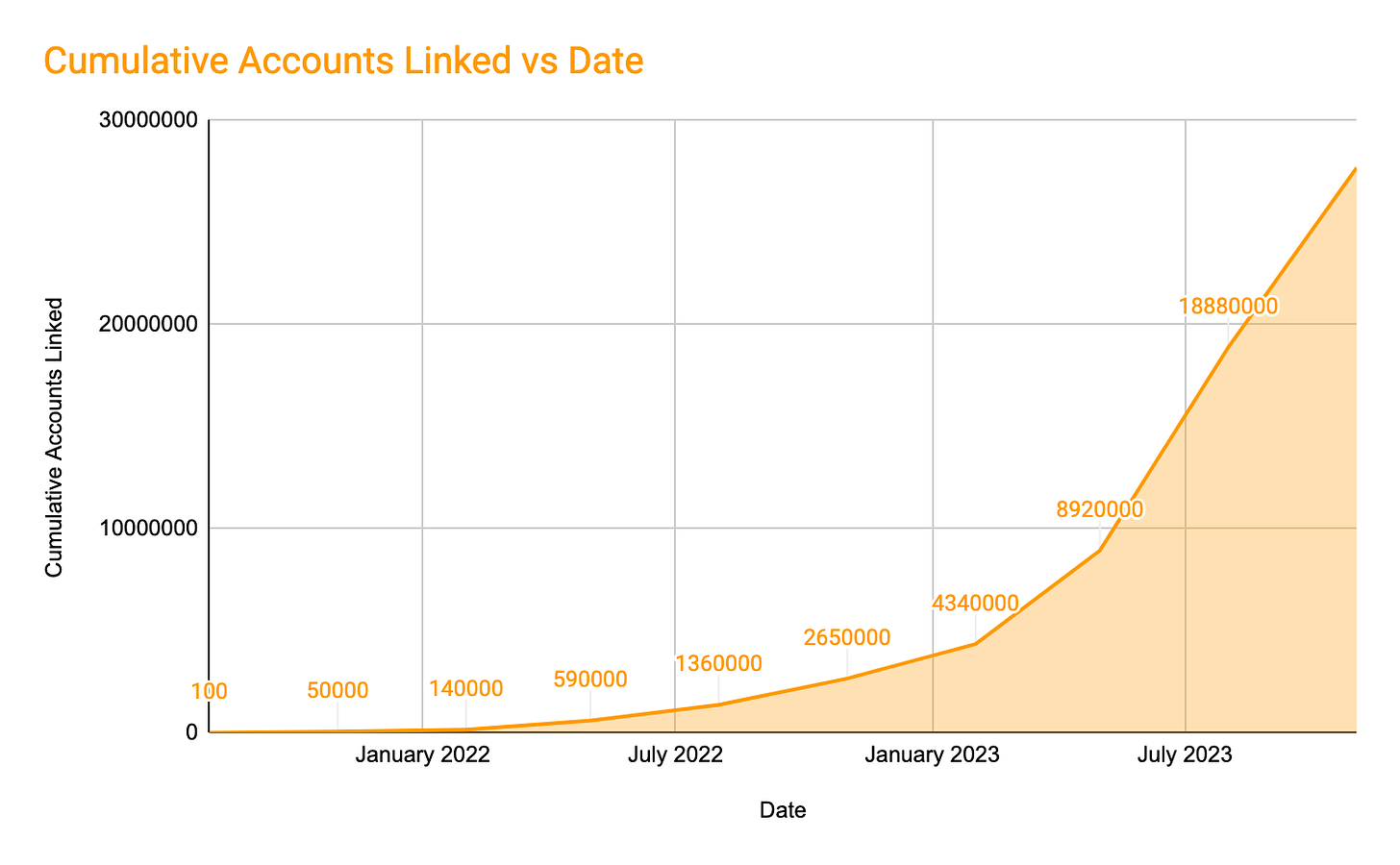

This graph shows the adoption curve for account aggregators since their launch in August 2021. As you can see, this curve has a textbook “holy shit this thing is taking off like a rocket” shape. 28.4M accounts have been linked in these two years, and the average month-on-month growth rate for the past 6 months has been above 26% with no signs of slowing down.

Two prongs? Fintech trident? What the bloody hell are you talking about?

We have already covered the orbit-shifting national project known as India Stack in great detail before, so we’ll make this quick.

India is still a relatively poor country with several problems, but it used to be a poorer country with much more pressing problems. One of the biggest issues was the fact that even as recently as 2008, only 17% of Indian adults had a bank account.

We take for granted today the fact that India is a fintech trailblazer, but just take a second to really let this sink in. Just fifteen years ago, less than one in five people in this country had a bank account. They had no safe place to store their money, no way to get cheap credit, and had to subject themselves to expensive and risky intermediaries to send money to their friends and families. The scope to build financial security was slim because the foundations of the building site simply didn’t exist.

In tackling this malady, India took a radical new approach - they would build population scale software systems to overcome the deficiencies in the country’s physical infrastructure. They would call this Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI), and it would be rolled out in three phases.

Phase 1 was intended to help with the most obvious problem - the fact that nobody had bank accounts. This was partly due to the fact that nobody had any formal ID, which is something a bank needs in order to confirm your identity and give you an account. In fact, in 2008, a whopping 400 million Indians lacked ANY kind of formal ID.

So in came Aadhaar, a biometric ID system that rapidly covered 99% of the population and gave them a way to electronically verify their identity. This ID mechanism was super convenient because it allowed banks to replace their slow and expensive physical document verification, handling, and storage workflows with an instant electronic flow built on computers and fingerprint readers. The World Bank estimates that this brought the customer onboarding cost for an Indian bank down from $23 to $0.15, a 99.995% decrease in cost. Fast forward to 2017 and 80% of people had bank accounts. Boom, first phase successful.

And then, Phase 2. Given that the population now had bank accounts, we needed a way to make them useful. The paper-based and web-based payment systems of the past were never going to cut it for a population that needed fast, cheap, and user-friendly solutions. The answer had to be mobile, and it had to be quick.

Enter UPI, the second prong of the fintech trident. It is a mobile-first, real-time, account-to-account payments system that has taken the world by storm. A lot has already been written about UPI (including by us), so we’ll skip the details. If you want to understand how it works at the granular level, this blog post by Setu is the best literature on the topic.

All you need to know is that Phase 2, like Phase 1, was an unprecedented success. 90% of adults now possess bank accounts, and they are using them to make 10 billion mobile payments on UPI every month. And these aren’t just retail payments, they are also payments made to merchants and businesses. In 2016, there were some 5 million point-of-sale terminals in the country. Now, there are more than 250 million of them thanks to UPI and its interoperable QR code system. Small merchants have a very cheap and convenient way to accept digital payments and boost their businesses. Unified Payments Interface? More like Uber Pleased Indians, amirite? No? Ok sorry.

So Phase 1 gave everyone bank accounts, and Phase 2 catalyzed a rapid proliferation of financial data in the form of all these electronic transactions that were now being recorded in the system.

Phase 3 is about harnessing the power of this financial data to stimulate an explosion of low-cost, high-quality financial services. Services like lending, insurance, investment advisory, wealth management, and tax planning. We desperately need this stuff, because it helps people move up in the world.

We need people to invest in the financial markets so that they can grow their wealth as the country grows. We need them to get insurance so that they have a safety net against emergencies and shocks to their lives and livelihoods. And we need them to get loans because credit literally makes the world go round. It is lifeblood for businesses that need working capital to tide over operations or invest in growth. And it is the enabler that allows many individuals to afford life-changing purchases of things like houses, vehicles, and education.

Unfortunately, these financial services need people to have good quality data for them to work. At the very least, they require consumers to have money and assets. In India, most people don’t have much money or wealth. So they are going to need good quality data.

And that is exactly where Account Aggregators - Phase 3 of the trident - come in.

So what exactly are Account Aggregators and how do they work?

Literally speaking, Account Aggregators (or AAs) are a newly-created class of Non-Bank Financial Companies (NBFCs) regulated by the Reserve Bank of India. They were first conceptualized a long time ago, but they were officially notified via this RBI Master Directive in September 2016.

From that point onwards, it took almost five years for AAs to go live in August 2021. It’s been a little over two years since they launched publicly, and the system is in the midst of a rapid scale-up.

OK aside from the chronology and literal definitions, how do they actually work?

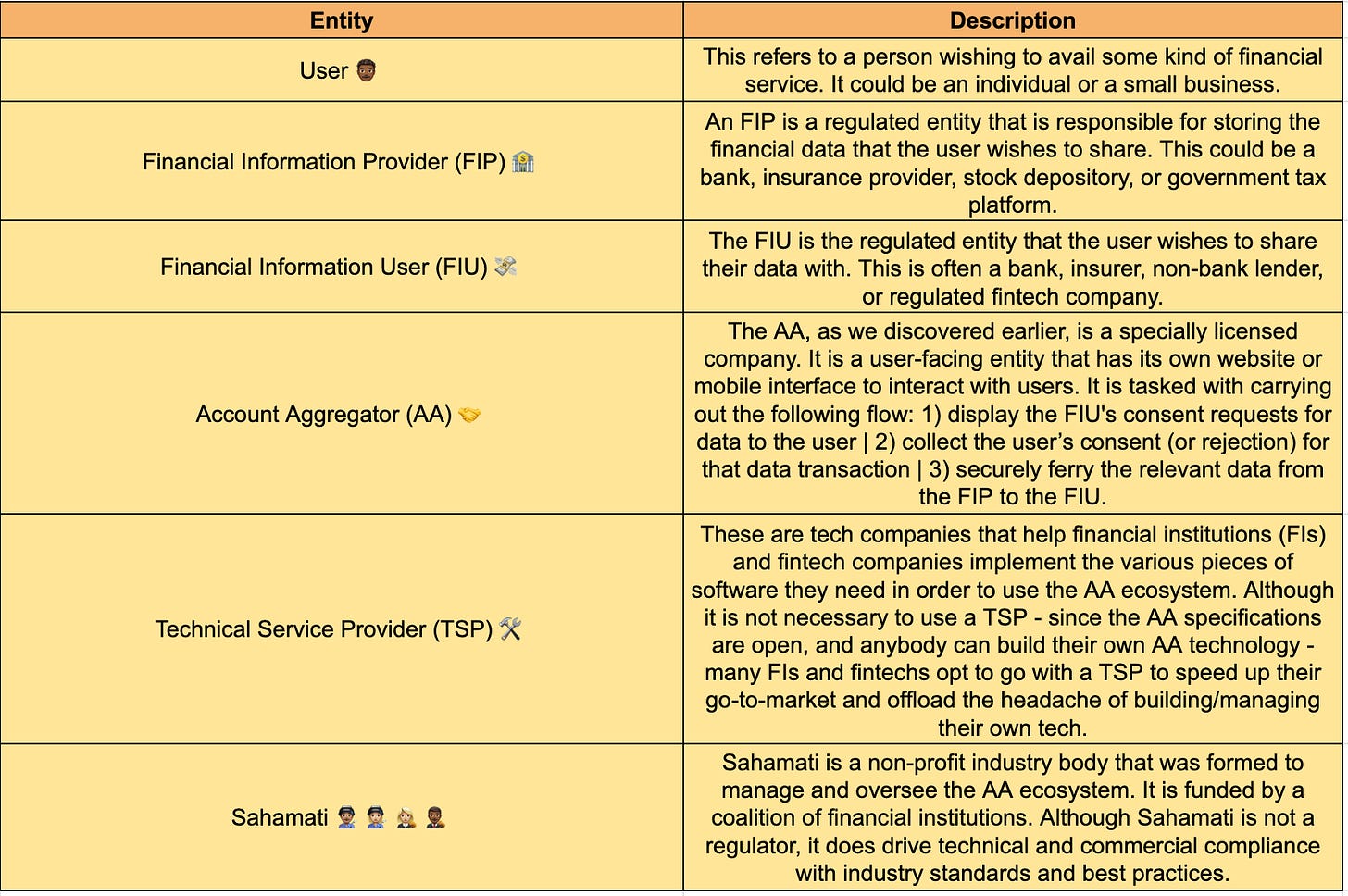

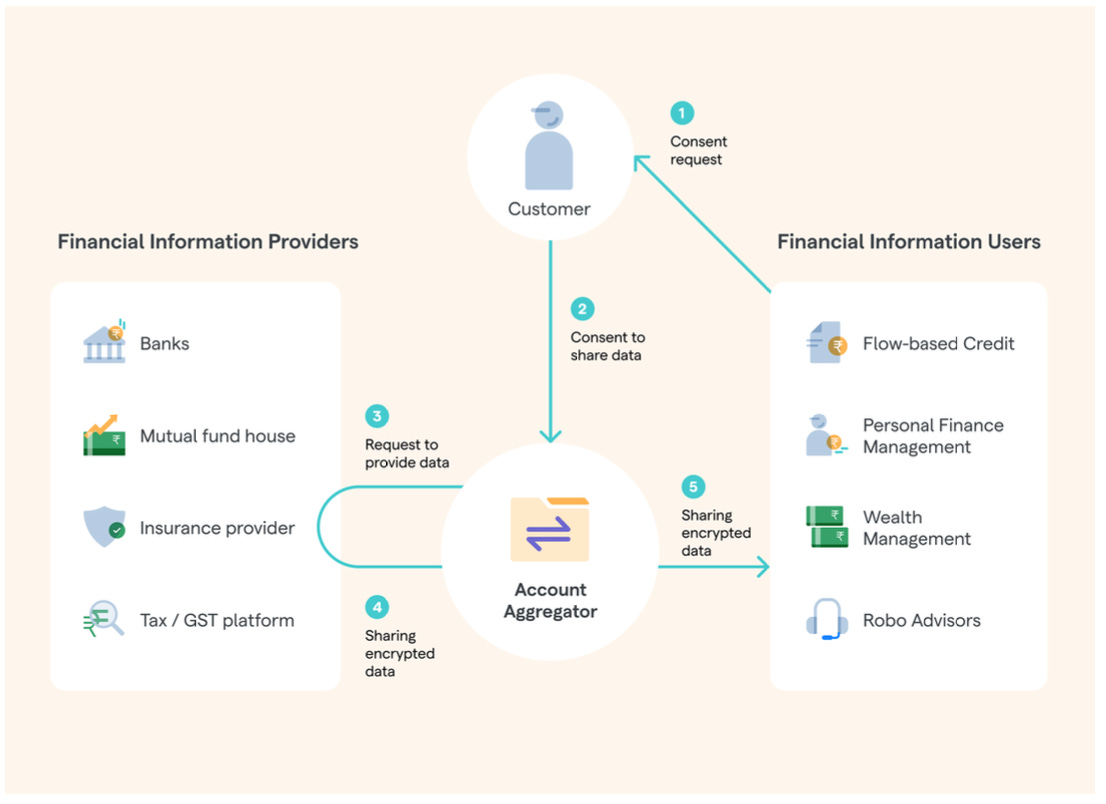

Account aggregators have a simple function - to securely and efficiently transfer financial data from the place it is stored to another place it is needed, with explicit user consent. To break down how this works, let’s first identify some of the entities that participate in this ecosystem.

Now, in order to understand how the system works, let’s look at the user flow and spotlight what is going on under the hood at each stage of the process.

On-boarding and account linking

The first step in the flow is that a user must sign up to and receive a virtual handle from one of the licensed AAs in the market. This can be done either by downloading a given AA’s mobile app, or it can be done as part of an embedded flow within some FIU’s app. Signing up is just as easy as entering a name and mobile number, which results in the user being issued a handle from the AA such as aaryaman@finvu.

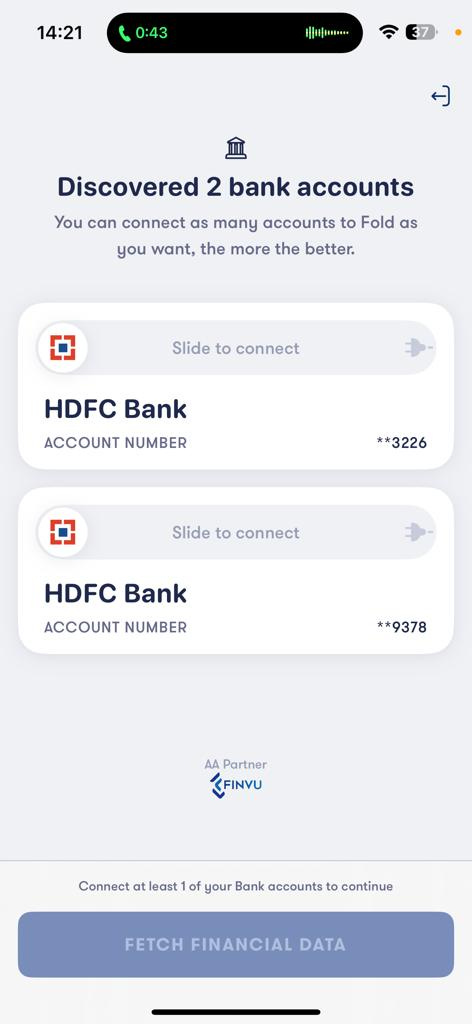

The second step is for the user to link their handle with their FIP accounts (bank accounts, stock holding accounts, tax accounts etc). In the screenshots below, we can see a butter-smooth account linking process facilitated by an AA called Finvu through their embedded interface which lives inside the iOS app of a regulated startup called Fold (they have a Retirement Advisor license from PFRDA). The FIP accounts in question are held in HDFC bank.

All the steps you see above take place within the gorgeously designed Fold iOS app, powered by Finvu’s software development kit (SDK) which creates a sort of private enclave within Fold through which the user and AA can exchange information securely. In the first image, the AA has fetched all of the user’s bank accounts. In the second image, the user is prompted to link those accounts with the AA by verifying a bank-issued OTP. Once the account linking is complete, the user can start to make consent transactions.

Making a consent transaction

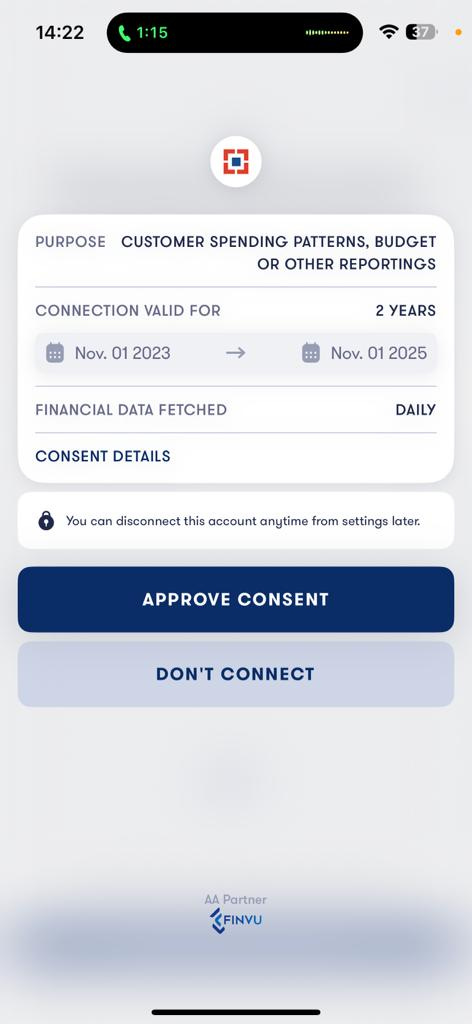

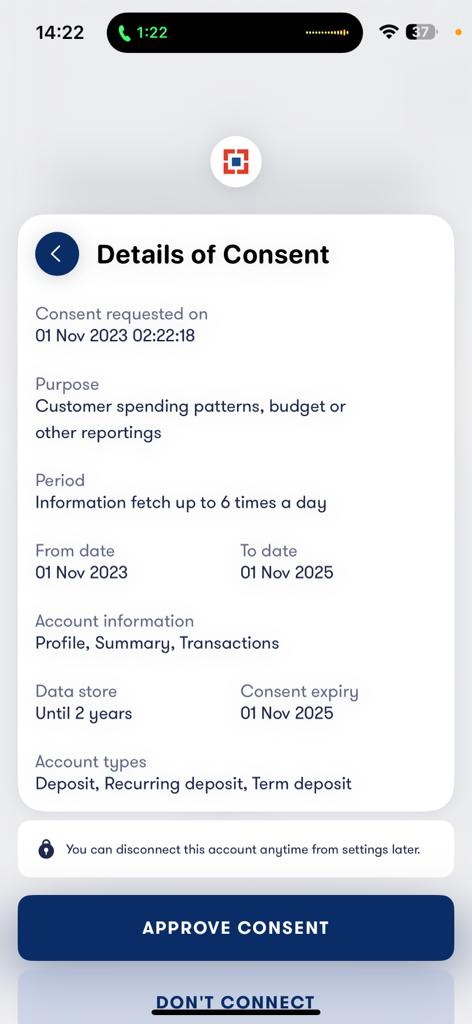

Now, in order to share our data with Fold, we need to give them consent to access our data. Thankfully, the Indian Ministry of Electronics and IT has a very clear definition for electronic consent. It must be a machine-readable, revocable document that clearly defines what data is being requested, how long it shall be stored for, what purpose it shall be used for, and how frequently the data can be fetched or refreshed.

As you can see in the screenshots, all of the necessary details are clearly presented in the consent request. So the customer just has to hit approve to complete the consent transaction. Once the user accepts this consent request, the AA generates a signed consent artifact (like a digital contract basically) containing the terms of consent the user has agreed to. This consent artifact is then sent by the AA to the FIP, in this case HDFC bank.

(In this example, we are seeing an embedded consent flow wherein the Finvu AA is performing its duties inside of a secure enclave within the Fold app. This is done to simplify things for the user and minimize friction. It would also have been possible for the user to bring their own AA handle to Fold separately.

In that case, the user might have downloaded another AA app such as Agya, created a handle and linked their accounts, entered that handle into Fold, received a consent request on their Agya app, signed Fold’s consent request from within the Agya app, and then returned to the Fold app. So yeah, you can see why embedded AA flows are so popular, especially now when the system is new and most people don’t have any pre-existing AA handles).

Fetching the user’s data

When presented with the consent artifact, the FIP prepares the relevant data by organizing it into a standardized machine-readable format, encrypting it, and digitally signing it. The AA then takes this encrypted data and ferries it back to Fold, which decrypts and uses the data (the AA itself cannot decrypt and read the data, only the FIU can do this).

(To try out an interactive demo of this whole process, visit this link from Setu. The OTP in all cases is 123456, and the FIPs selected should be Axis Bank and ICICI Bank).

But why is this needed? Isn’t it possible to do all of this today?

You are right, observant reader, that it is possible to share financial data today. But the reality is that the existing methods of data sharing leave a lot to be desired.

There are two main ways to digitally share financial data today.

#1 PDF/Image Uploads

This is one of the most common ways we share our financial data currently. We download our bank statements or account statements, and then we upload them wherever they are requested. This method of data sharing is quite annoying for users - especially if you need to share one or two year’s worth of data. Nobody wants to wrangle dozens of PDFs from an old bank website and then manually re-upload all of them every time you wish to apply for a loan.

But while this is only moderately annoying for users, PDF uploads are very annoying for financial providers to ingest. Companies ingesting financial data from PDFs need to employ specialized algorithms to parse the PDF text or optically recognize the characters on the page. These algorithms are not always accurate, and are often costly to build or buy. To make matters worse, the algorithms need to be adjusted or tailored to fit every data provider’s unique way of presenting their data. For instance, an ICICI bank statement has a different format from an IndusInd bank statement. The algorithms employed to parse the bank statements of these two banks have to be customized to account for these differences. This becomes a big headache to manage, especially when one considers the sheer number of different data providers and their ability to unilaterally break your algorithm by changing their data format without notice.

The biggest problem, however, with PDF or image uploads is that they cannot be verified. It is possible to doctor these documents, which further increases the cost and complexity of using them as sources of truth for financial decisioning. Some Indian lenders have confessed that up to 4% of their credit losses have come from borrowers who were later revealed to have doctored their financial documents. In an industry where a single percentage point of credit losses could be the difference between profits and insolvency, this fraud issue is a big problem.

#2 Screen-Scraping / Reverse Engineering Mobile APIs

The other prevalent technique for sharing financial data today is screen-scraping. To employ this technique, an FIU must first collect the user’s banking username and password.

Once inside the user’s account, the FIU deploys an algorithm that scrapes the relevant information straight off of the HTML that comprises the webpage.

Reverse-engineering of mobile APIs is very similar to screen-scraping. In this instance, the FIU takes the user’s mobile banking credentials and fires off queries to the bank’s server in order to get the desired data.

In both of these instances, the main benefit is 100% accurate and truthful data. After all, the data is coming directly from the bank’s website or mobile app server.

The downside of this approach IS THAT THE USER LITERALLY GIVES THEIR BANKING LOGIN TO A STRANGER ON THE INTERNET. Over and above that, the same issue from PDF uploads still abounds. Namely, an FIU has to maintain different scrapers and APIs for every single bank. On top of that, a single change to the bank’s HTML or API format will cause these data pipes to break. Many celebrated fintech companies like Plaid, Tink, Truelayer, and Yodlee were built using this technique.

How is the Account Aggregator system better than these options?

I’m glad you asked. Let’s first consider the benefits to the user:

Smoother and easier workflow: Linking an FIP account is a one-time activity that takes less than two minutes for the user. Approving a consent request is literally one click.

The consent can be revoked at any time: Revocability is a cornerstone of the AA architecture. When a user revokes consent, the FIU must delete the data they have stored for that user.

It is far more private: Using the AA does not involve sharing sensitive login details with strangers on the Internet. It is also theoretically possible for users to filter the financial data they share. Imagine being able to share only your average balance, or only your Swiggy transactions, or only the transactions above 5K rupees. All of this smart filtering has been planned for in the AA architecture (although it is not live yet).

Now, lets look at the benefits for the FIUs:

Sweet, sweet standardization: The FIUs get data in machine-readable and standardized format. So there is no need to have a separate algorithm to parse each document type issued by every FIP.

No fraud: The data is coming directly from the FIP in a digitally signed format, so there is no risk of fraudulent data.

Lower processing costs: Since there is no fraud and there is no need to build and manage dozens of algorithms for data ingestion and cleaning, costs go down significantly for FIUs. An online lender called Snapmint revealed (pg 13) that moving to the AA framework brought their cost of processing a loan application down from Rs. 440 to Rs. 100.

More revenue: Thanks to the ease of use, the user-drop off rates in AA-enabled flows are much lower than the drop-off rates for traditional PDF-upload flows. This excellent Sahamati document attests that Finbox and Snapmint have seen 2x and 5x lower user drop-offs amongst AA users in their loan application workflows, respectively. This widening of the top of the user acquisition funnel translates to more completed loan applications and more revenue for these online lenders.

Taken together, all these things should benefit users, financial service providers, and the whole economy.

What kind of data are we talking about here, is it only bank statements?

Ah, this is one of the coolest things about the system. The architects of the AA framework have taken a very forward-looking view and built out the capability to share all kinds of financial asset data.

There are currently 22 financial instruments which have been spec’d out on the AA system, and 15 of them are already active. Let’s break them down according to the regulator who oversees them.

As you can see, that is a lot more than just bank data. In fact, that list covers almost all the financial assets that an individual or a business can own. To check which specific FIP is live with a given data type, look up all the banks here and all the non-banks here.

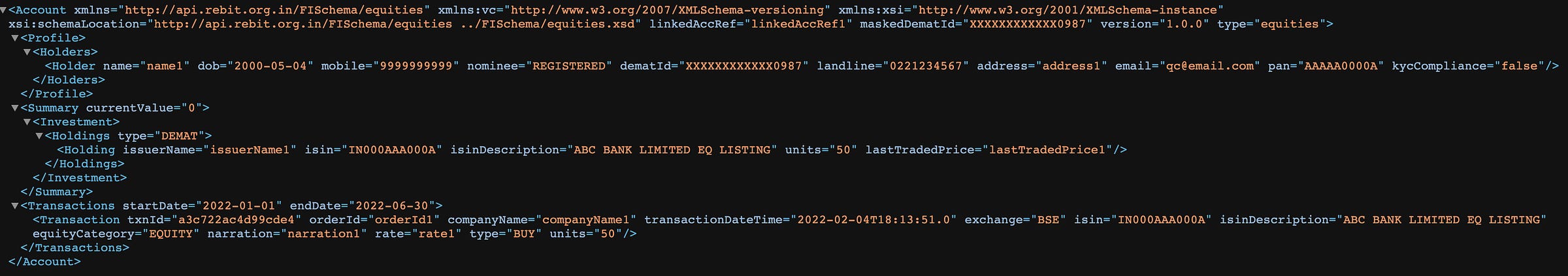

For each of these data types, there exists an RBI-mandated standard data schema that all ecosystem participants must conform to. Here is an example of the standard for equities data, written in the XML format.

The masochistic or learned amongst you would have noticed that the standard includes information about the holder of the equity, the holdings eg. current value and last traded price, the issuer information, and all the transactions taken place for that equity. These data points are also broken up into three sections: ‘Profile’, ‘Summary’, and ‘Transactions’. Profile contains information about the account holder. Summary has high level information about the holdings and their current value. The Transactions section has the details of every order or transaction placed. The existence of these chunks makes it such that the FIU and FIP don’t need to move ALL the data every time unless required. They can decide whether they need one, two, or all three chunks, which saves time and energy.

It’s a similar story with all the other data types as well - there is a lot of information in these specs which can be useful for consumers and businesses. A little later, once we have gotten the ‘how does it work’ stuff out of the way, we will take a lot at what this could be used for and why it is useful.

Who pays for this? Is everything free? Why would any banks sign up to this?

Great question. The system is not free. FIUs must pay the account aggregators in order to use this system. Presently, FIPs are not paid for providing data, but that will likely change in the near future.

For the time being, banks and other FIPs have four non-monetary incentives to integrate with the system and offer their customers the ability to consentingly share their data:

Reciprocity: A bank or financial institution can only be certified as a Financial Information User if they also sign up as a Financial Information Provider. Certain entities - such as non-deposit taking NBFCs - don’t possess user data for any of the 22 financial instruments mentioned in the list above, so there is no data for them to share. But banks do store things like deposit data. And since banks definitely want access to the sweet, cheap, high-quality AA data to power their own lending operations as FIUs, they must also sign up as FIPs or face RBI’s wrath.

Increasing the Size Of the Pie: Banks make money mainly through lending, but they are more conservative than nimbler fintechs, who are able to employ technology and innovation to create new products and often onboard new, first-time borrowers. This is good news for the banks, because it results in an expansion of the market. These new products and borrowers did not exist before, so the banks aren’t losing out in some zero-sum game. On the contrary, the banks are benefiting because digital lenders are forging new paths for the banks to grow too. Once the fintechs have proven the merit of a certain product, borrower profile, or lending methodology, the banks can partner with those fintechs to jointly lend or the banks can build their own capabilities to offer those products solo. After all, the banks will have the advantage of the lowest cost of capital, so they always have a seat at the lending table. If somebody brings more food to that table, its good for the banks too.

Consumer Demand Pressure: When UPI was launched in 2016, only 7 banks came on board. Predictably, the big banks were not rushing to implement an unproven payments system which would give them less revenue and control over the user than the status quo. This all changed, however, when banks realized that the growing popularity of the product might push some of their customers to switch over to UPI-enabled competitors. This is a real issue - I am in the process of setting up a new bank account because I am frustrated with my bank’s slow adoption of account aggregators. On a side note, there are now 477 banks that are live on UPI. Consumer demand always changes markets. 🤟🏾

A changing policy environment: The Indian parliament recently passed the Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDP) of 2023. This law enshrines certain rights of ‘data principals’ (ie. consumers). Amongst these is the right to obtain, update, and cause erasure of any data held about them by a third party. In other words, the government is taking people’s data protection rights seriously, and banks who abstain from joining the AA framework - a system set up specifically to give consumers more access and control over their data - won’t be earning brownie points from either the government’s financial inclusion champions nor from the incoming Data Protection Board of India.

So how much does it cost to use this system?

Given the nascency of the system, the pricing model is understandably fluid. Having said that, the current pricing methodology is based on the nature of the use case and the frequency of data fetches.

The most prominent use case for the fledgling AA system is to fetch a user’s bank data for the purpose of underwriting a loan. This is a one-time activity so the pricing for this use case is quoted on a per-transaction basis. On average, Account Aggregators are able to charge lenders 50p - 2 rupees per lending transaction (with larger lenders with higher volumes able to command better pricing).

To put this in context, when I first wrote about the AA framework - back in this 2019 blog post - industry incumbents I spoke with quoted the cost of pulling and analyzing a borrower’s bank statement using PDF parsing at 30-100 rupees per transaction.

Already, before the AA ecosystem has even taken off at country scale, the direct cost of accessing bank statement data has already shrunk by some 50x. That is very good news for lenders, and for small borrowers.

The second use case that is coming up is personal finance management (PFM). In this use case, FIU apps need to pull users’ data frequently in order to give them up-to-date information on their finances. Currently, many FIPs have the capability to only support one or two pulls per day. This number is going to go up very soon but currently, FIUs pay Account Aggregators about 2-20 rupees per user per month for ~35 data pulls.

What is important to note here is that it is not the use case itself that dictates the cost, but rather the frequency of data pull. For instance, a bank wishing to monitor a borrower’s spending patterns in real-time as part of its early warning loan management systems may opt for daily data refreshes and end up being billed like a PFM app. On the other end of the spectrum, a dating app that wishes to incorporate income verification may only need to pull a user’s financial data once, so that will be reflected in the pricing.

Wait, dating apps can use this system? Who exactly can be part of the Account Aggregator ecosystem?

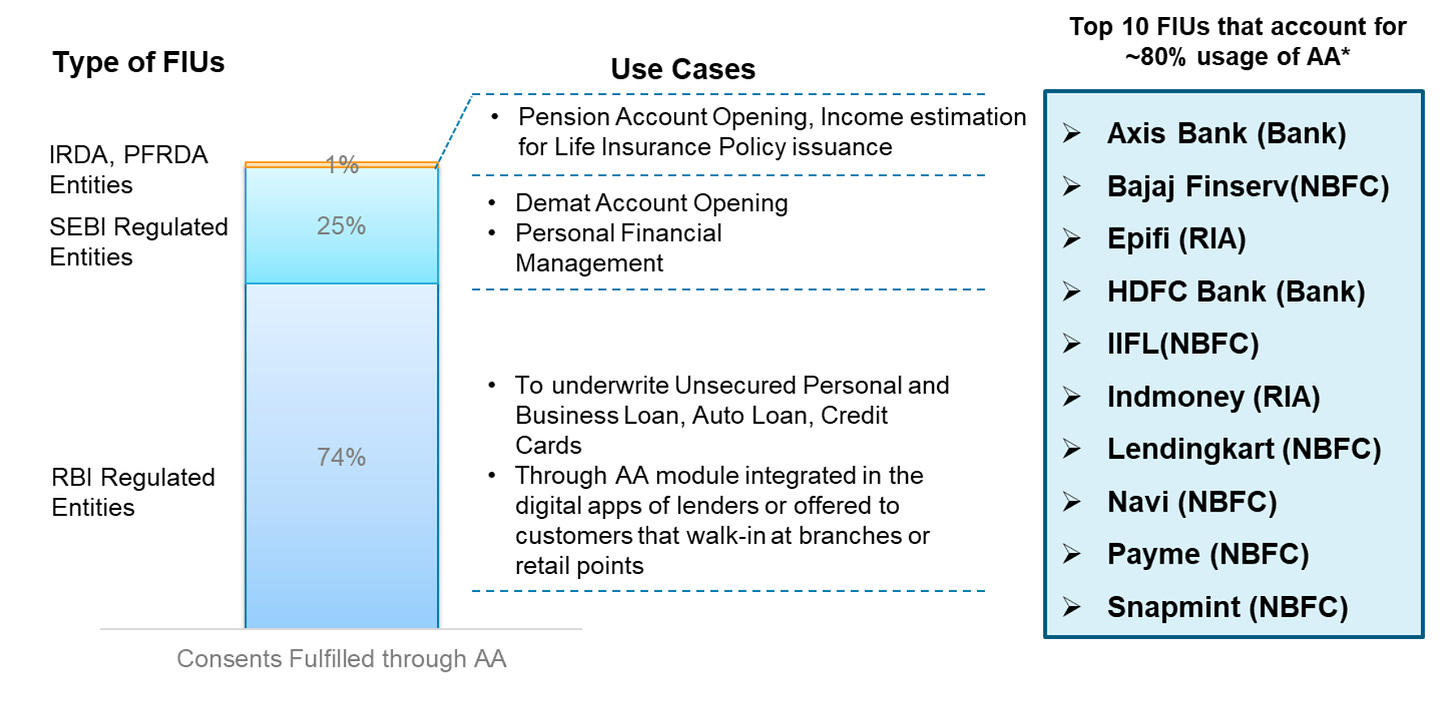

Oh yeah, this should be clarified. As it stands, only regulated financial institutions can become FIPs or FIUs. Namely, entities regulated by RBI, SEBI, PFRDA, and IRDAI. So while this may change in the future, corporate participation in the system is presently limited only to regulated entities.

On the user side of things, individuals and sole proprietorships can sign up to an AA and begin linking their accounts. Full corporate current accounts are not yet supported but are coming in the future.

How can regulated startups get involved - what are the steps they need to take?

Well the first step is to build out the relevant technology. The AA ecosystem adheres to a set of technical specifications governed by ReBIT (RBI’s technology division). Whether you wish to be an AA, FIU, or FIP, you will need to build out certain technical modules that are in line with these specifications. This makes it so that integration with other members of the ecosystem can be seamless and does not require painful and lengthy custom integrations between each AA and all FIUs/FIPs.

In fact, this same approach to technical standardization also extends to the legal and commercial domain. Rather than make every AA go and ink an independent commercial agreement with every single FIP and FIU, Sahamati has a multipartite legal document that helps ecosystem participants agree on key obligations and responsibilities off the bat. Companies are just required to sign this document - known as the Account Aggregator Participation Terms - once, at which point they are in accord with every other ecosystem signatory on the basic issues. Commercial terms and pricing matters are left out of the Terms to allow for free-market price discovery and service customization.

Anyhow, once you’ve built out the relevant technology you need to be compliant with the system standards, you have to get certified. Sahamati has empanelled a number of companies that provide testing, consulting, and certification services to AAs, FIPs, and FIUs.

It is also possible to get certified by proxy. That means that you can get a free pass on getting directly certified if you have your technology modules built out by a certified Technical Service Provider (TSP). Once you have your technical certifications in place and legal contracts done, you can begin using the system.

At this stage, it is worth making the following two points:

There is a role for non-regulated players! They can be Technical Service Providers. This means that they can build tools to help FIPs and FIUs connect to AAs or leverage the data that comes in through the AA pipes.

Getting regulated is not impossible. Startups are free to apply for licenses from any of the regulators. Here is a list of all the license types offered by RBI, SEBI, PFRDA, and IRDA.

So what are some of the cool things that people could build using this system?

Business Loans: Since the AA framework covers current accounts for sole proprietorships and can also pull GST tax data, it is insanely useful for lending to small businesses. GST data in particular is huge because it contains verified information about a company’s transactions, customers, invoices, suppliers, and other key commercial metrics that are useful for a lender. This use case probably constitutes around 50% of the overall volumes of the system at present.

Income Verification: Using the AA system, you could pull an individual’s bank statements and employee provident fund data. This would help you understand their income level and historical employers over time. This data could be used to power social media networks, dating/matrimony apps, Glassdoor-style anonymous forums, and more (with the caveat that it would have to be regulated FIUs building these products). This is also useful for investors wishing to prove that they satisfy SEBI’s income thresholds needed to trade futures and options on the stock market (which is the most profitable activity for trading apps, so they push this in a big way).

Personal Loans/Loans Against Assets: Personal loans don’t need any explanation, but loans against assets will also receive a shot in the arm thanks to AAs. It will be possible for lenders to easily fetch data to lend against the value of a user’s stocks, mutual funds, AIFs, SIPs, pensions, or provident funds. Watch this space.

Personal Finance Management/Multibanking: This is expected to be a huge use case. The pitch is to have all of your asset information in one place, including your balances and transactions across all of your bank accounts. Interestingly, many major Indian banks have implemented this feature in their digital banking apps, so multibanking (as it is known), has become table stakes. The more advanced companies in this segment (like Fold) will have to offer better analytics, insights, and value-add to stand out from the rest.

Cloud Accounting: The idea here is to help small businesses manage their books and filings by consolidating their assets in one place, and reconciling their financial transactions with cash flows. Interestingly enough, Tally Solutions - the maker of India’s eponymous and ubiquitous accounting software used by millions of businesses - has just gone and got itself an AA license 🤔

Wealth-Management/Social Investing: Its not universally clear where PFM ends and wealth management begins, but I do expect to see companies build things like robo-advisors and wealth advisory platforms using AAs. “Hello customer, I have noticed that you have some free cash lying in your savings account, why not move it to this higher interest rate account or liquid fund instead?”. Or perhaps this could be used to build a powerful social investing app like eToro or Public where users can discover and connect with their friends and others based on their investment positions. Maybe the facilitation of secondary market transactions could also be a part of that? SEBI has recently mandated the dematerialisation of many financial assets so a lot of stocks and AIF units exist in purely digital format now.

Insurance Advisory: The pitch would be: fetch and store data of all your policies in one place. See if you are undercovered, overcovered, or would benefit from a change of policy. Get reminders on policy expirations and premium payments and also get support with claims. Its also worth mentioning that insurers are using AA data in their actuarial models to help understand a customer’s profile and risks.

Tax Support: If a fintech has all the banking and accounting information for an individual or a company, could they help that person or company with tax planning and filing? I am certainly no expert on tax, but it seems plausible.

Other Use Cases: There are myriad other uses cases that could be enabled by AAs, including risk management for payment aggregators and bank account verification for things like payouts to the nominees of a life insurance policy holder (replacing the current practice of penny drops ie. the dropping of a small amount of money in an account to verify the owner’s details.)

The opportunities to build better products and experiences seem manifold. The data is coming online. Now it is just up to people to build.

What does the market landscape look like?

The market landscape has come a long way in the past few years. Here is how the ecosystem looked in August of 2021.

And this is what the ecosystem looked like in May of 2023.

As you can see, there has been a real Cambrian explosion of ecosystem participants, especially when you take into account the growth that has taken place in the last 5 months. At the time of writing, there are 506 entities in various stages of onboarding to the system, including 123 live FIPs (compared to just 58 live FIPs in the graphic above). So this market landscape is already much, much, wider than what the graphic shows.

Huh, thats strange - PhonePe and Policybazaar have AA licenses? Why?

Account Aggregators make money from FIUs for collecting user consent and ferrying user data. Perhaps these companies with large user bases have obtained licenses because they justifiably believe they have an edge when it comes to distribution and customer acquisition (not to mention high trust and brand recall in matters pertaining to finance).

Alternatively, it may be the case that these companies signed up as AAs to own every piece of their tech stack and deliver the best user experiences. I’m not sure how I feel about this. It is clearly not feasible for every consumer company to go and get its own AA license. There would be too much confusion in the market and users wouldn’t want to link their accounts with a new AA every time they use some fresh app. The regulators would eventually pull the plug on fresh licenses and then it would be M&A season.

What’s more, I don’t know if I agree with the notion that possessing an AA license is the only way to deliver the best customer experiences. The customer experience is already very smooth in many of the apps I have tested out. I guess what I’m saying is this - the entrance of big consumer players into the AA space makes some sense, but it’s still so early that it’s anybody’s guess how this phenomenon will play out.

What about the market size? Is the market really big enough for companies like PhonePe to want to get involved?

Before examining how big the market for AA services could get, let’s take stock of how big the market is presently.

In the past 30 days, there have been almost 5 million new FIP accounts linked on the system, and a similar number of successful consent requests fulfilled. If we annualize this number, we get about 50M consents per year.

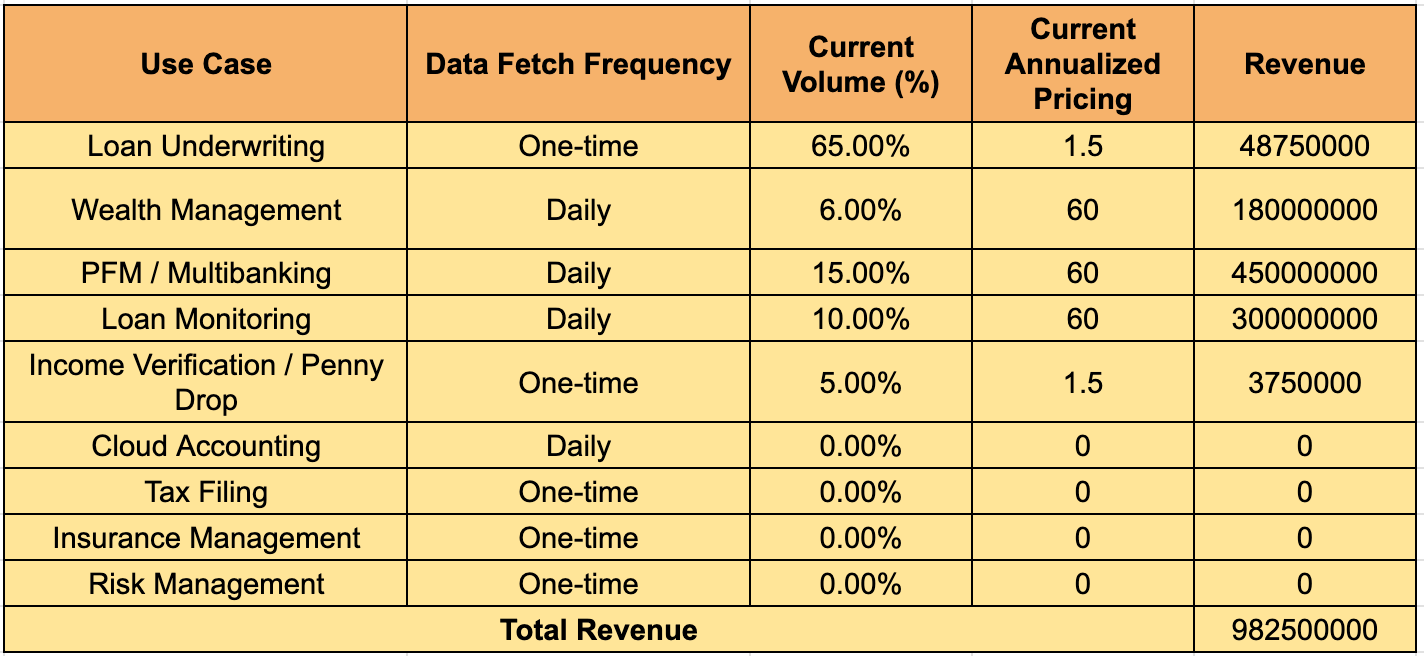

Our research suggests that the numbers shown below are broadly accurate both in terms of use case distribution and pricing.

What this gives us is a current market size of around 98.25Cr ($11.7M), just for providing data fetching for FIUs. Any additional revenue streams that AAs might generate - such as ads, subscriptions, any form of cross-selling - are outside of this scope.

Now, to get a decent picture of how big this could get, we can compare Sahamati’s work in this arena with public figures for the Indian market. Sahamati estimates that by 2027, the number of consent transactions made in a year will reach 5 billion. That is about 100x of where we are today, which is 50M/year.

At this point, I’ll be real with you - none of my models or estimates look clean enough to make it into this post. I conducted a bunch of different analyses to extrapolate how many consent requests we could see per year by 2027, and they got fairly messy.

One approach was to go industry by industry. I used population data to estimate the PFM/multibanking/wealth-management volumes. For lending, I collated public data about the number of retail loans disbursed per year (240M, but that number seems way too low), commercial loans disbursed per year (2M), the ratio of loans disbursed vs assessed (~35%), and a number of other statistics.

I did the same for insurance, trying to do the math on how many life insurance policies there are in India (the Life Insurance Corporation alone has more than 250 million customers and sells over 20 million new policies per year), how many general insurance policies are sold annually (~290 million), and how these figures might translate into consent requests.

At the end of all of this, I played around with the key assumptions including the pricing and the percentage of all products which would employ AAs versus other means of data collection. Whichever way I sliced the data, I came to a market size of around INR 6000-9000Cr per year, or about $780M-$1.08B/year.

Uhhh… Is that big? That sounds big.

I think so too. It certainly sounds large enough to support multiple companies, but we’ll have to see whether these assumptions play out.

And pricing? Is it just a race to the bottom?

It might be. While AAs do ultimately provide commoditized data, they can still differentiate themselves on the basis of service, performance, and usability. Therefore, pricing will need time to stabilize, and it will also depend on key factors such as whether FIPs need to get paid for sharing data.

But in a pricing analysis that was shared with us, a leading TSP assumed that the lowest the price of an AA data fetch might fall to is 7 paise ($0.00084), which is the cost of sending a single SMS through a telecom company like Route Mobile.

Even at those kinds of prices, the market sizing exercises we were a part of still forecast AA revenues in the 6000-9000Cr range. And this is all within the existing scope of Account Aggregators today.

Huh, what do you mean by that?

Currently, the system is concerned with financial assets only. The entire liabilities side is left out. That would include things like credit cards, loans outstanding, and credit bureau data. Non-financial data types such as telecom data, civil data, and health data could also theoretically be added to the system, as could the functionality to actually trigger WRITE operations instead of just READ operations (ie. take actions on behalf of users - eg. making payments - instead of just reading account balances), but most of this stuff will probably never happen. There is already so much to do just on the financial asset side of things.

Certainly sounds like a lot. How about investment opportunities? Where might VC or PE shops think of deploying capital?

So we’ve already discussed the revenue potential of AAs themselves, as well as the benefits that open up for FIUs, who are certainly set to enjoy a golden run.

I guess what we haven’t discussed is the TSP and middleware opportunity. As you might recall, TSPs help FIUs and FIPs come onto the AA system. This is important because many financial institutions are not technology companies, and they have antiquated backend systems that were simply not built to handle anywhere near the kind of scale that we see in the financial sector today. Billions of UPI transactions and data requests are flying around every month - somebody has to think of the poor banking servers and build solutions to help them scale. TSPs can do this, and they can earn well while doing so.

On the FIU side, a popular pricing model we see in the market is that the FIU pays their TSP to just handle all the legwork. Building out the core FIU tech modules, integrating with all AAs, negotiating pricing with all AAs, and using the optimal routes to fetch data - the FIU just leaves this all to the TSP who charges a premium on top of whatever the underlying AA commands per data fetch. The FIU just foots the overall bill at the end.

Along with the raw data itself, TSPs (and other software companies) are also well positioned to earn off analytics and data governance solutions. Analytics would include things like enriching the raw data that comes from AAs, building pipelines to manage and manipulate that data, and offering things like credit scoring or user profiling on top.

Data governance means helping the FIUs ensure that they can never lose or misuse the customer’s data. With the DPDP Act now in effect, financial institutions are wary of breaking the law. After all, the Act stipulates that entities found breaching the data protection rights of their customers could be fined up to Rs. 250Cr per breach! So if a customer’s consent expires or is revoked, the FIU better make damn sure they delete that data. TSPs and other software vendors can provide this kind of technology.

Lastly, there is also a big white space for professional services. While this market may not necessarily be venture scalable, there will definitely be lots of demand for service providers who can help with certifications, licenses, legal contracting, and UI/UX design. At least before the AI overlords eat away at this market, but that’s a topic for another time…

What about the issues? Surely some things are breaking and going badly?

Definitely. Lots of things are still suboptimal, let’s look at all of them.

FIP Reliability.

The biggest issue has been FIP reliability. For the longest time, success rates for this system were extremely low. If you tried to discover a user’s FIP accounts, link them, or fetch data, you simply got nothing. The reason for this is that banks have been slow to implement these systems at scale. Even today, the level of AA penetration in the market would be much higher if we just had better reliability rates.

Thankfully, this problem has been getting much better over time. Sahamati actually worked with the ecosystem to build a dashboard which tracks the success rates and response times of all banks on the system. This has marked out the stragglers who are not pulling weight.

Interventions like this, along with many pushes by the central government and RBI, have led to big improvements in FIP availability. Success rates across the ecosystem now sit at around 60%. This is an improvement, but it is clearly a long way off from where it needs to be.

Interoperability In Theory Alone

The AA framework is supposed to promote interoperability. A customer should be able to use any AA to link with any FIP and share data with any FIU. This is only the case in theory. In practice, a lot of AAs are not supported by various FIPs and FIUs.

This is not for lack of technical interoperability. Instead, it is due to legal and contract issues. Some ecosystem players just don’t have pricing agreements with each other, so they don’t link up their systems. This is mostly due to concerns over bandwidth - many banks are not ready for their old core banking systems to take these new volumes, so they onboard new AAs slowly.

The interoperability challenges also extend to the data. Some banks have differing ways of presenting things like transaction IDs and timestamps, and that can cause problems for FIUs.

Awareness

Very few people in the country know what AAs are or how they work. Industry insiders think the number of people who have used an AA is below 0.3% of the population.

For this initiative to succeed, we need a mass awareness campaign that can educate users and help them understand that AAs are secure and reliable ways to improve the quality of one’s financial services.

Luckily, RBI has brought in the right man for the job…

Performance issues

For once, I’m not talking about those kinds of performance issues... I think. What I mean is, latency is high. It takes a long time to receive data from FIPs.

The data is also shared on a ‘pull-basis’, meaning you have to ask for it and then wait for the FIP server to respond. Sometimes, it can take time for the data to be prepared, so it would be better if there was a ‘push-based’ mechanism that just shared the data when it was ready. An asynchronous mode for data sharing that didn’t require the requester to just stand around waiting for something that may not even come.

UX issues

To make the user experience better, AAs and FIUs want to implement auto-discovery flows whereby user accounts can be automatically fetched from all FIPs without a user having to specify which specific FIPs he has an account with. The FIPs do not want to do this because they can’t support that kind of traffic - they want to only be bothered when one of their customers has specifically selected them.

Another common UX issue is that FIU legal names are often incongruous with brand names. For example, Slice is the brand name of a popular fintech. That is the name that everyone knows. However, the legal name of the NBFC that Slice lends through is Quadrillion Finance. When a user approaches Slice for a loan, the regulation mandates that the paperwork and consent requests be made in the name of Quadrillion Finance. This can confuse users.

The good news with all these issues is that many of them are eminently solvable. Most of them are simply teething issues, and there is every reason to believe that Sahamati and the ecosystem players can work them out in short order. After all, even UPI was plagued by low success rates in the first few years of its existence.

You keep mentioning Sahamati, what’s the deal? Who is she, a regulator?

Sahamati is not a person, nor is Sahamati a regulator. Instead, it is a non-profit industry body that is supported by network participants and policy makers. It runs independently, and is funded by ‘members’ - namely AAs, TSPs, FIUs, and FIPs. While it does not have the ability to make regulations, it plays the anchoring role in mobilizing the ecosystem and enforcing the existing rules.

Sahamati is responsible for spreading awareness about the AA framework, monitoring the effective functioning of the system, creating fora for ecosystem participants to come together and collaborate on improvements, and just make the system work overall.

Sahamati also provides some technical infrastructure required for the system to work efficiently. They operate two central services which help FIUs, FIPs, and AAs discover, authenticate, and securely communicate with each other. One thing that should be clear at this point is that unlike Aadhaar, the AA framework is a protocol, not a platform. It does not rely on a central server or system to function. Instead, it is a federated system which works because it allows disparate parties to connect directly with each other using a common protocol. Even if the Sahamati central services were to go down, they could easily be spun up by somebody else and the system would be able to keep working.

So taking everything into account, Sahamati clearly has a lot of responsibilities and a big job on its hands. Luckily, they have a fantastic team and a stellar group of advisors and steering committee members that are more than up to the task.

OK you’re becoming less and less funny, and this thing has gone on for far too long. Let’s wrap it up. Where do we go from here?

It’s a very exciting time for Indian fintech. Between Aadhaar, UPI, and the AA framework, the country’s financial rails have been completely reshaped. We are now in a position to push on and bring better quality financial services into the lives of over a billion Indians.

And there is no reason that our ambitions should end at the borders of the country. India is already the recognized global leader when it comes to digital public infrastructure - this much was clear at the recent G20 summit where India played the leading role in the sessions on DPI. I am sure that other countries will see the AA framework and begin to implement similar systems. This is an opportunity for us to go and export our technology and help the international community.

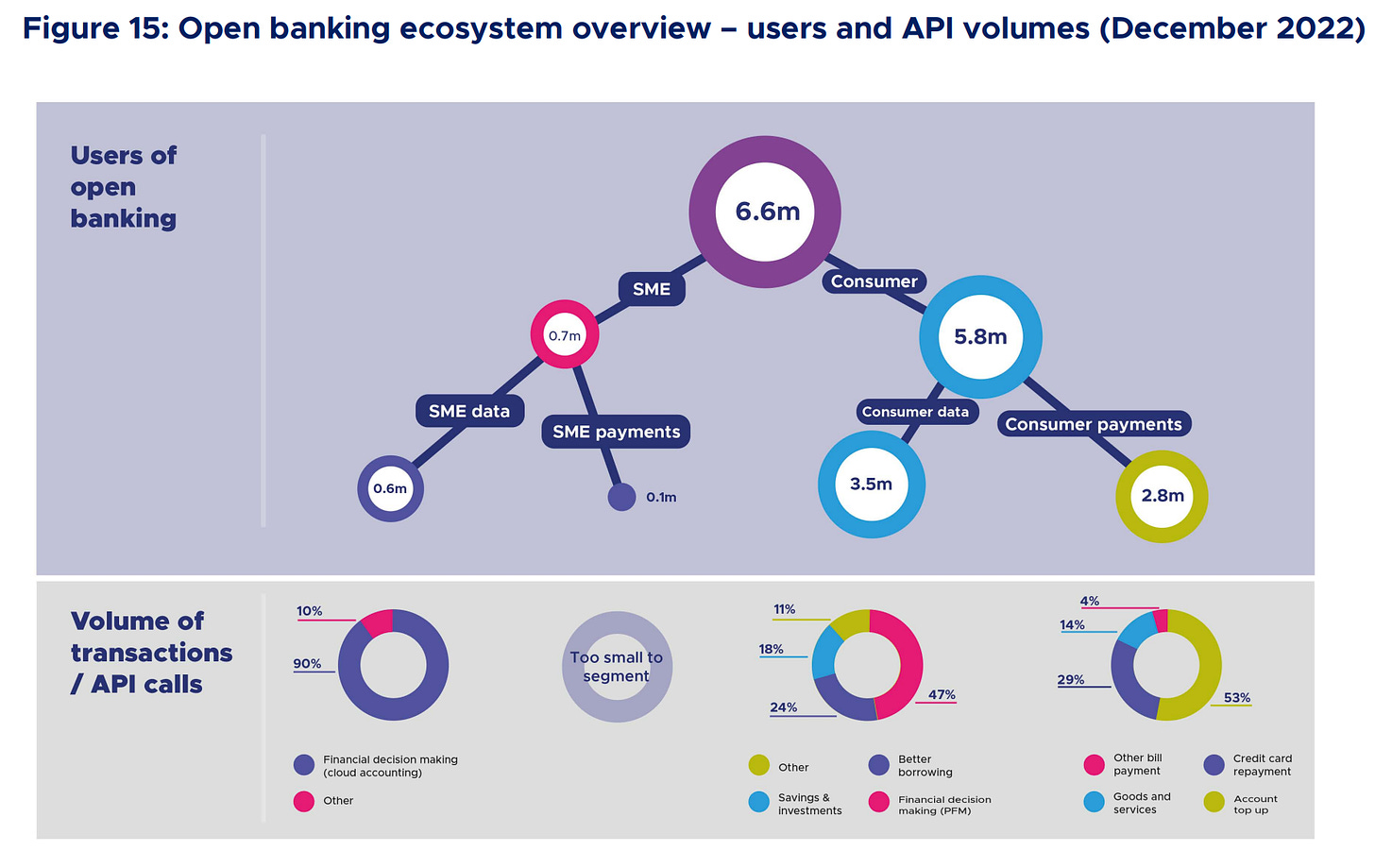

It must be noted however, that comparable systems have been launched in other countries before - most prominently the UK and the EU - but we have learned from their models and forged a different path. Hopefully other countries can also learn from our successes and failures and tweak things to match their unique contexts.

But before we get carried away tooting our own horn and talking about global expansion, we need to make sure that we succeed at home. To this end, we are lucky that we have an ideal triumvirate: a proactive and ambitious central government that really wants to spread the gospel of DPI, a competent and dynamic regulator that takes recommendations and delegates work effectively, and a large and willing private sector that is eager to contribute to the public commons and expand the overall size of the pie.

The next couple of years of Indian fintech are going to be very fun to watch, and I am glad we have a ringside view. Thank you for reading, I hope this essay was worth your time.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Akash, Nash Vail, Munish Bhatia, Nikhil Kurhe, Dheeraj Kumar, Sumit Gwalani, Nikhil Kumar, and Pete Jaison for their insights and support for this piece.

And thank you to Rahul Sanghi for tolerating my ridiculous and soon-to-be-banished publication delays.

Another brilliant piece. Thank you very much for sharing this in-depth overview of AA system. I read that there is one more national stack that Govt is planning to launch and its called National Health Stack. Would love to see you guys to bring a detailed piece on that as well.

Thanks for the in-depth article.