Ice Ice Bombay

On frozen fortunes and white gold - the epic tale of India's first luxury commodity

Hey folks👋

Welcome to the 464 new Tigerfeathers subscribers who’ve joined since our last piece.

If you’re still on the fence about signing up, here’s a small sample of the reviews we’ve received for our work in 2024.

What are you waiting for?👇

This edition of Tigerfeathers is presented in partnership with…TEAM

For the longest time Mumbai has played second fiddle (and maybe even fourth or fifth fiddle) to India’s traditional tech hubs like Bangalore, Gurgaon, Pune, and Hyderabad. In October 2022, a group of Mumbai’s leading startup founders came together to see if they could invert that order over the coming decade.

TEAM is the Tech Entrepreneurs Association of Mumbai (TEAM). It aims to be the straw that stirs the startup scene in India’s commercial capital. It’s mission is to see Mumbai become the “#1 destination” for tech founders starting up in India.

As someone from Mumbai who moved to Bangalore to join an early stage software company, it’s been cool to see the progress that TEAM has made just in the last 18 months. They’ve begun to lay the groundwork to meld the city’s disparate founders, developers, investors, policymakers and service providers into a single spirited community.

Their members today include the founders of Dream11, BookyMyShow, Upgrad, Zepto, MyGlamm, Haptik, Clevertap, Loginext, Faasos, Shaadi.com, Purplle, Upstox, Pharmeasy, Infibeam, and more.

Whether you’re starting up in Mumbai or just passing through the city, if you want to support the mission or just say hi; consider checking in with the TEAM👇

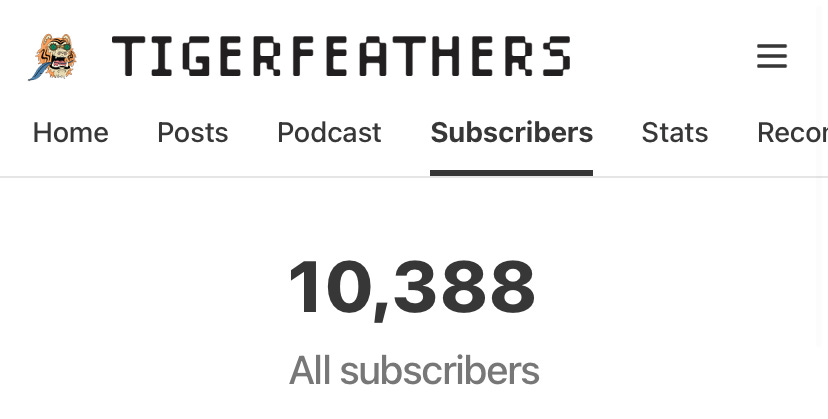

Before we kick things off today, a little update from behind the scenes. A couple of weeks ago we crossed a tiny milestone at Tigerfeathers…

The number above far exceeds the number of (presumably real) people we thought would be interested in (voluntarily) reading long-form text in 2024. We’re roughly four years and half-a-million words into this thing, and very grateful for everyone who’s been along with us for the ride. Thank you for reading, sharing, and tolerating our work❤️.

We’ve said before, the goal is to turn this newsletter into something of a time capsule for 21st century India, to unearth novel insights as a by-product of drawing a bridge from Indian history to present-day Indian tech. There’s plenty more to come on that front, both this year and beyond (including our first ever merch drop👀). Stay tuned.

That being said, even four years in, we are no better at predicting where the next piece is going to come from. To illustrate, our ONDC essay from February was extracted from countless meetings and interviews with VCs, founders, protocol developers and fortune tellers (jk). It was planned months in advance and brought to life over four months of research, writing, and general self-loathing.

Today’s piece, on the other hand, came from a walk.

Earlier this year when friend-of-the-newsletter (and former CTO of Product Hunt and OnDeck) Andreas Klinger was touring India, I joined him for a walking tour of Mumbai’s historic Fort area.

For one, this annoyed my girlfriend, who’s been asking me to do the same tour with her for the last three years. That’s a story for another day (maybe next month’s edition?). More significantly, this included a pit stop at the K. R. Cama Oriental Institute (below), a building I’ve passed by countless times in a city I’ve lived in for 82% of my life.

The Institute was founded in 1916 in honour of Kharshedji Rustomji Cama, a Parsi scholar and reformer who championed various social causes over the latter half of the 19th century. Today it mainly promotes scholarship and research into the ‘culture of the East’.

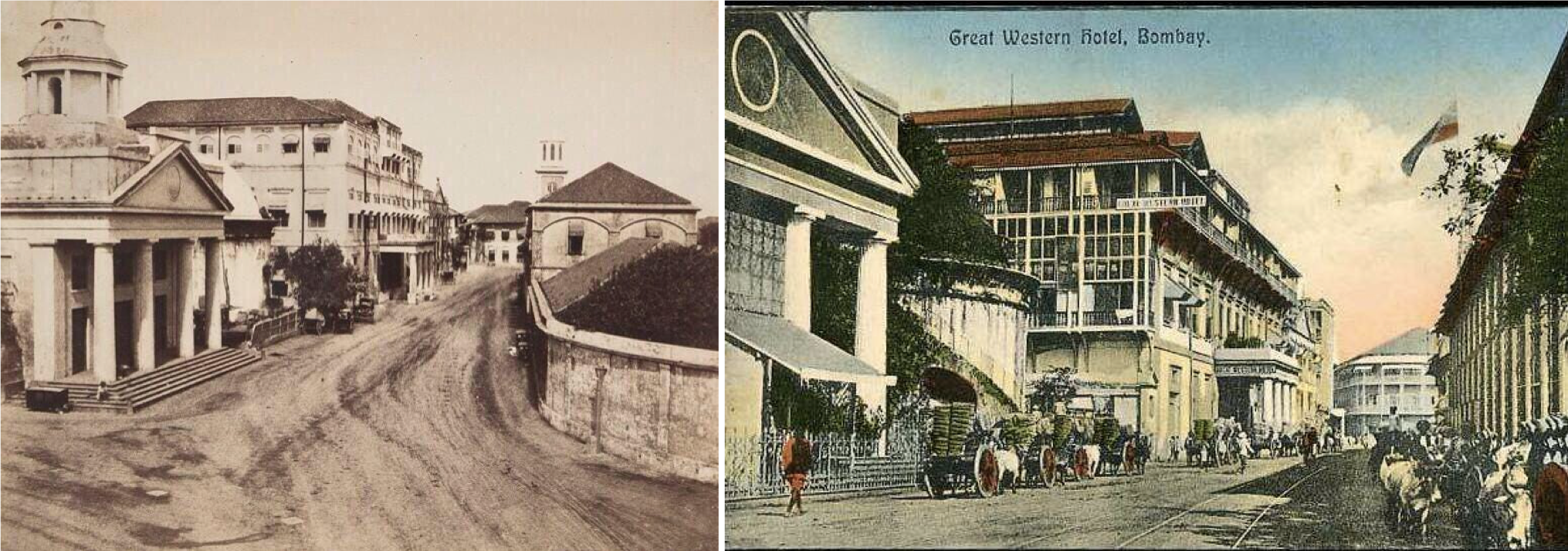

What I didn’t know (and what I’ve since realised is news to everyone around me), is that this building was originally the site of Mumbai’s first ice house. It was built opposite the old government dockyard, primarily to store and distribute ice to Mumbai’s colonial gentry for much of the 1800s. (It’s the domed white building on the left in the picture below).

Who cares about an ice house, you say? Well, this particular ice house was built in 1843, in a time when Mumbai was still Bombay, and India was still being ruled by a private corporation from Britain. It was a time before India had seen electricity (1879), before the first Indian railway was in operation (1853), and before any kind of industrial ice manufacturing operation was underway on Subcontinent (1878).

Given that ‘winters’ in tropical Mumbai only dip to (a bone-chilling) 17°C at worst, you could be forgiven for asking, as I did, “So where did the ice come from?”

The answer, is that ice didn’t suddenly arrive in Mumbai in the 1800s because of some errant snowstorm. It wasn’t the outcome of any industrial alchemy. It wasn’t brought in on horseback from the Himalayas and it wasn’t just found in a frozen cave in some shaded suburb of the city.

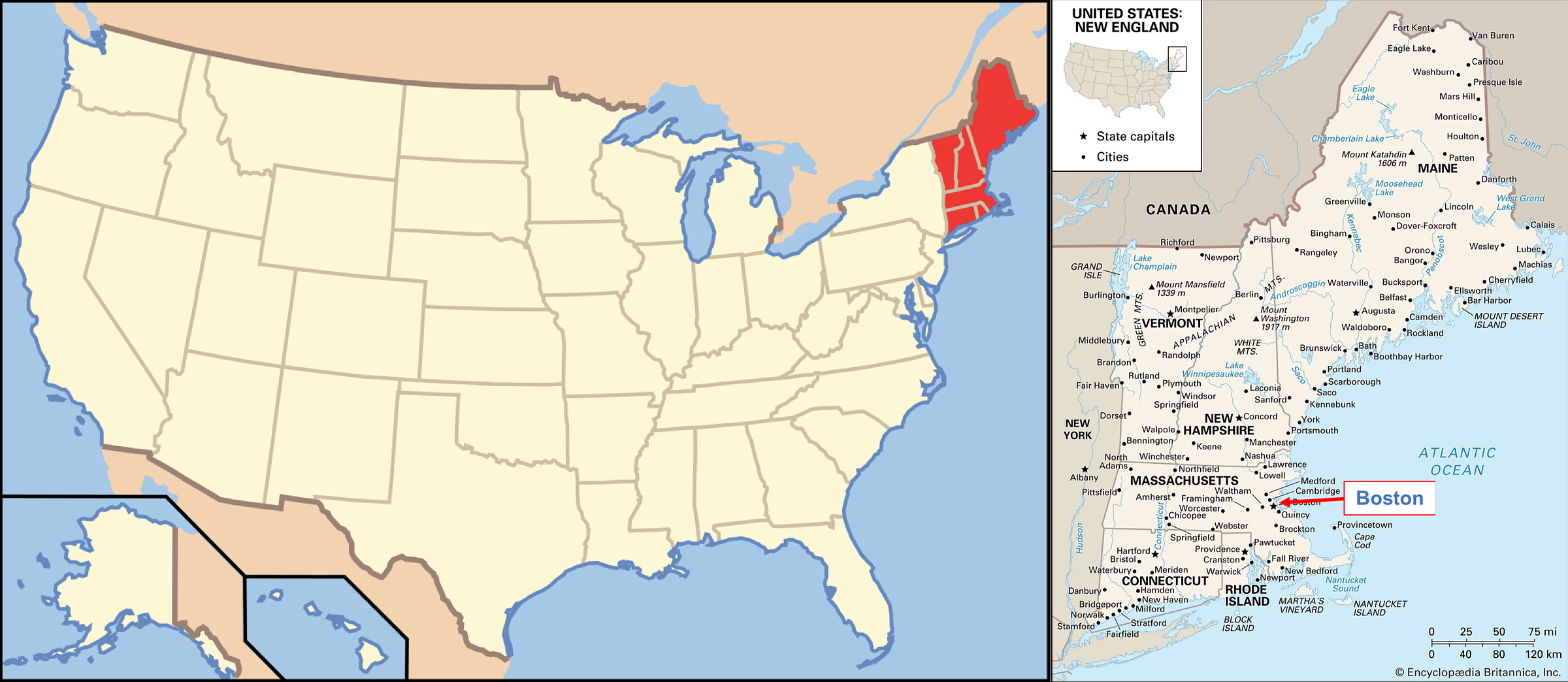

The ice came from Boston. In the United States. Cut from the surfaces of several frozen lakes across the state of Massachusetts in the depths of winter. And then shipped across the Atlantic over four months and 16,000 miles to the seaside seats of the British empire in Bombay, Calcutta and Madras (starting with the inaugural shipment of ice to Calcutta in September 1833). That’s how commercial ice first came to India.

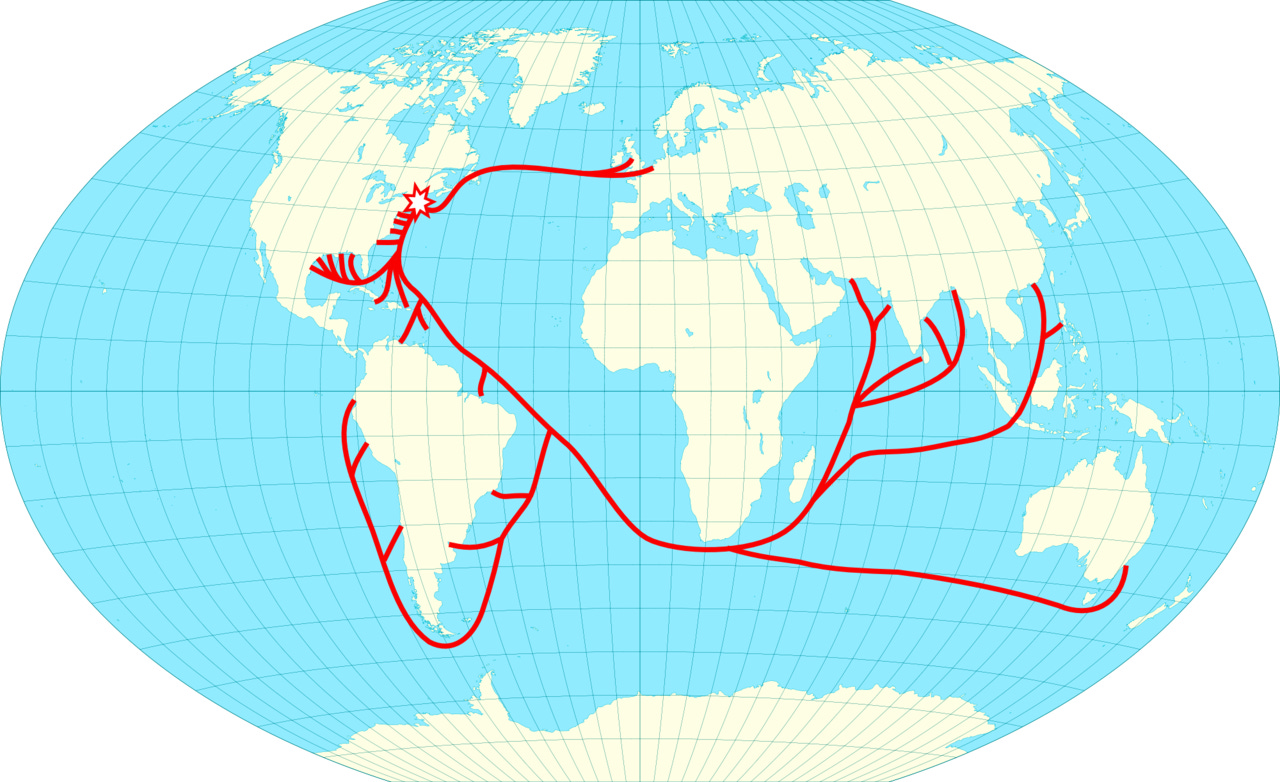

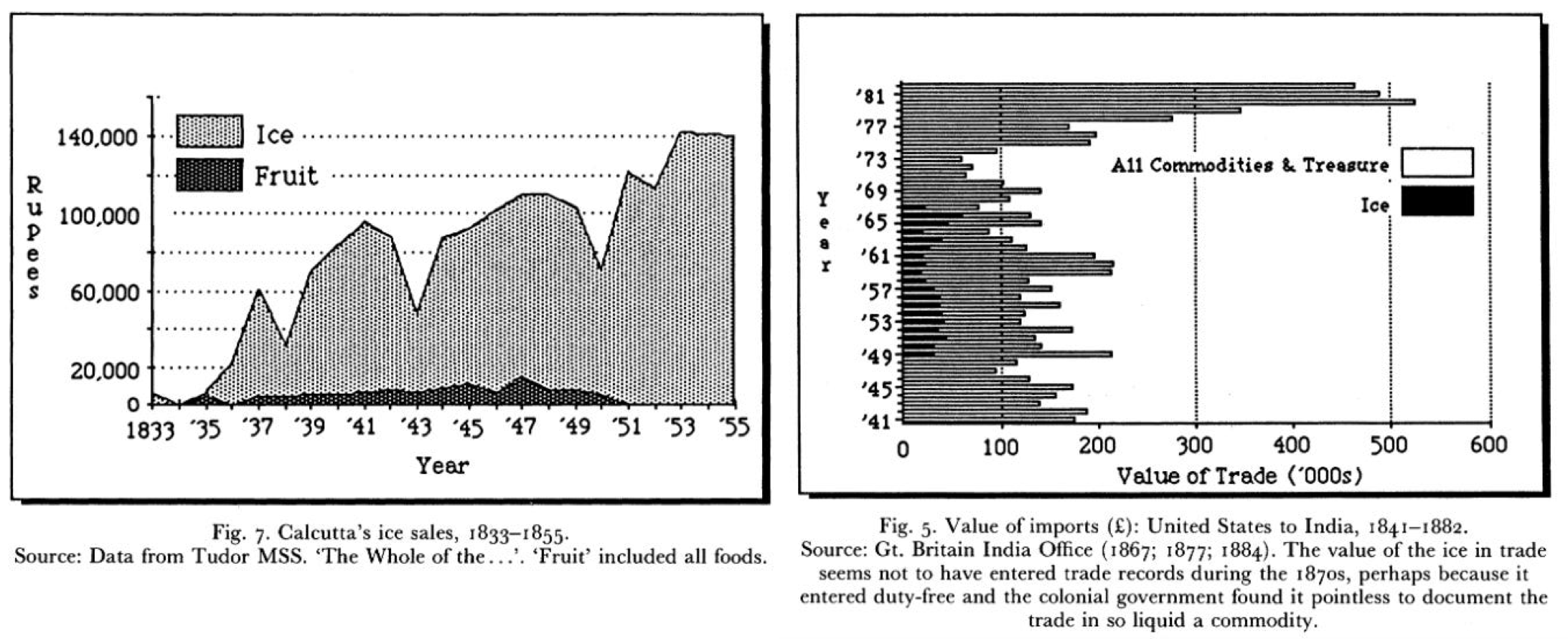

For the better part of a century, ice from the pristine lakes of New England, Massachusetts, found its way to exotic ports all over the world, from Cuba to Jamaica, Singapore to Rio de Janeiro, and - chief amongst all - to the Presidency towns of colonial India. In fact, in 1847 ice was the second-most traded commodity between the US and India after cotton.

Aside from being a neat bit of historical trivia, it turns out that the 19th century ‘frozen water trade’ is one of the most pivotal chapters in the history of global commerce. It literally changed the world. The exporting of ice was the exporting of cold comfort. It meant that people living in sweltering tropical locales could find temporary reprieve from the fury of the sun.

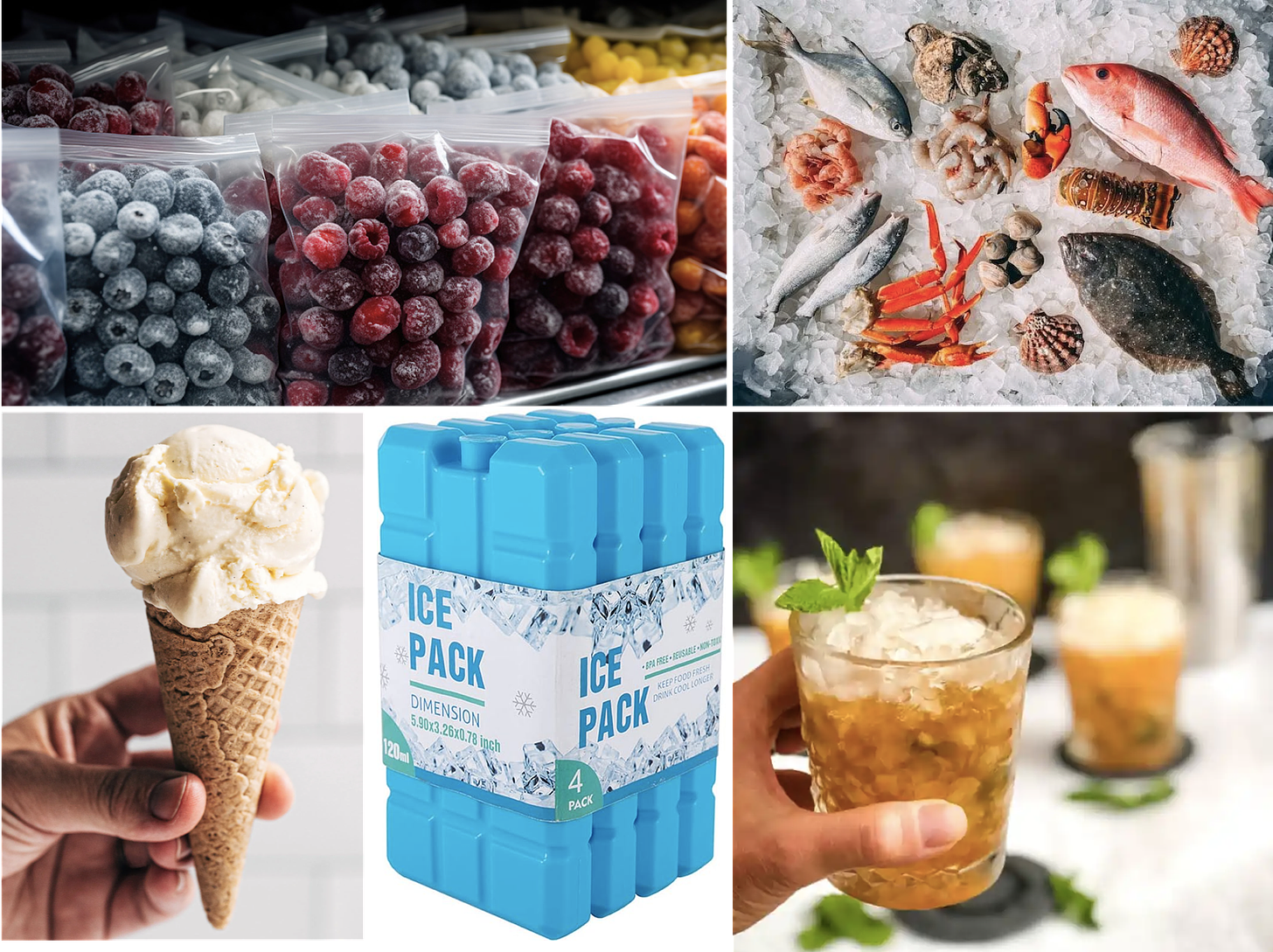

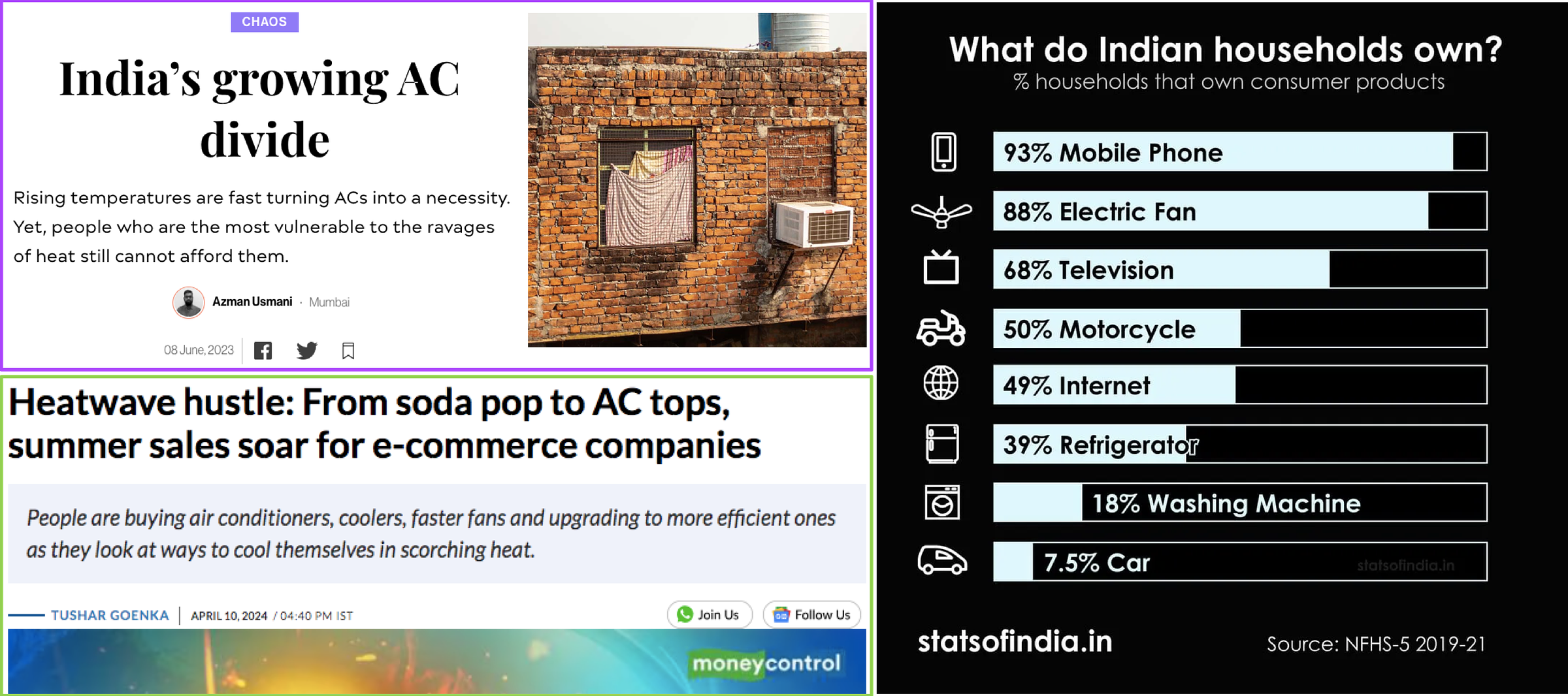

Think of how many times a day you interface with ‘artificial’ cold. Air conditioned office? Cold beer? Preserving fresh dairy and produce in your fridge? Applying an ice pack to an injury or a fever? Cold plunges?? (Huberman Hive stand up☀️💪❄️😴). Each of these modern conventions can be traced back to the discoveries prompted by the shipment of natural American ice around the world.

The ability to keep people and things cool in hot places also led to the creation of several industries that form a major part of the global economy today, including those for cold drinks, cocktails, meat packing, and home appliances like ice boxes and refrigerators, among others. The ice trade triggered the changing of global diets; it reconfigured the shapes of global cities; it improved public health; and most important of all, it led to ice cream becoming an ubiquitous everyday treat (instead of a luxury reserved for emperors and kings).

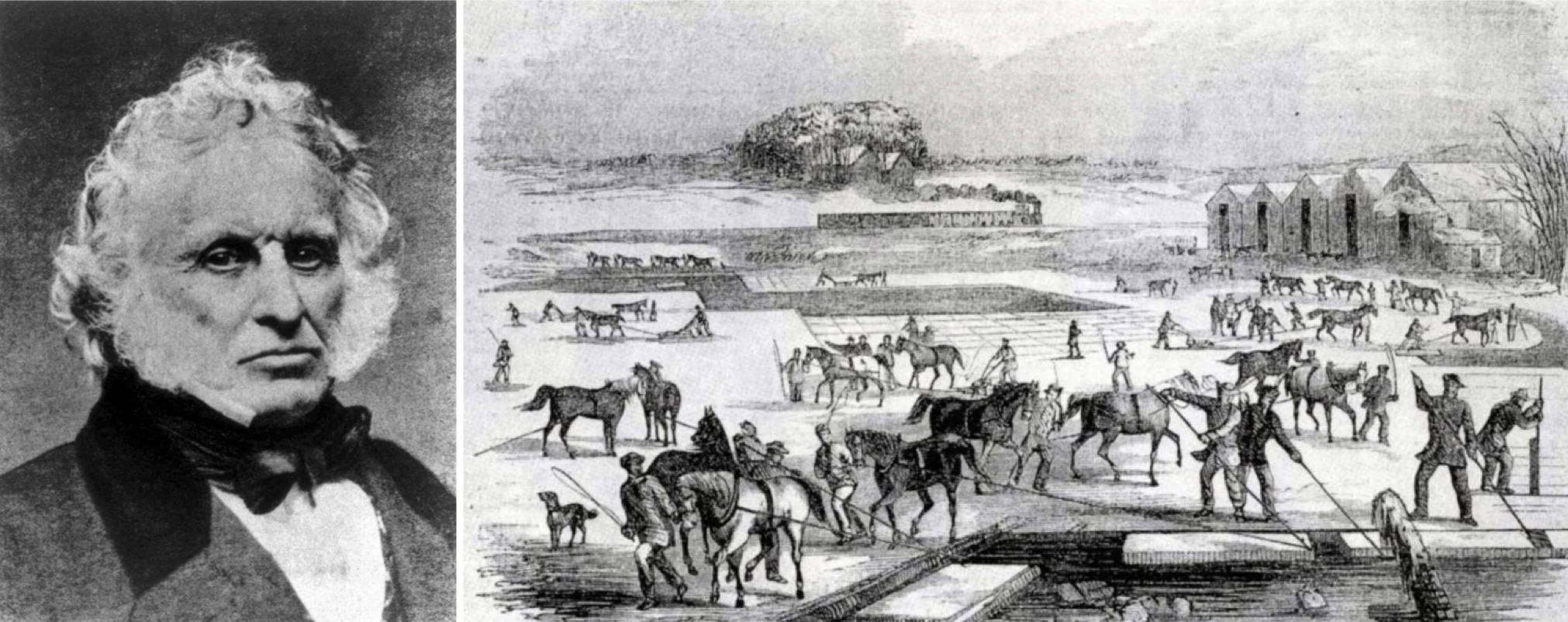

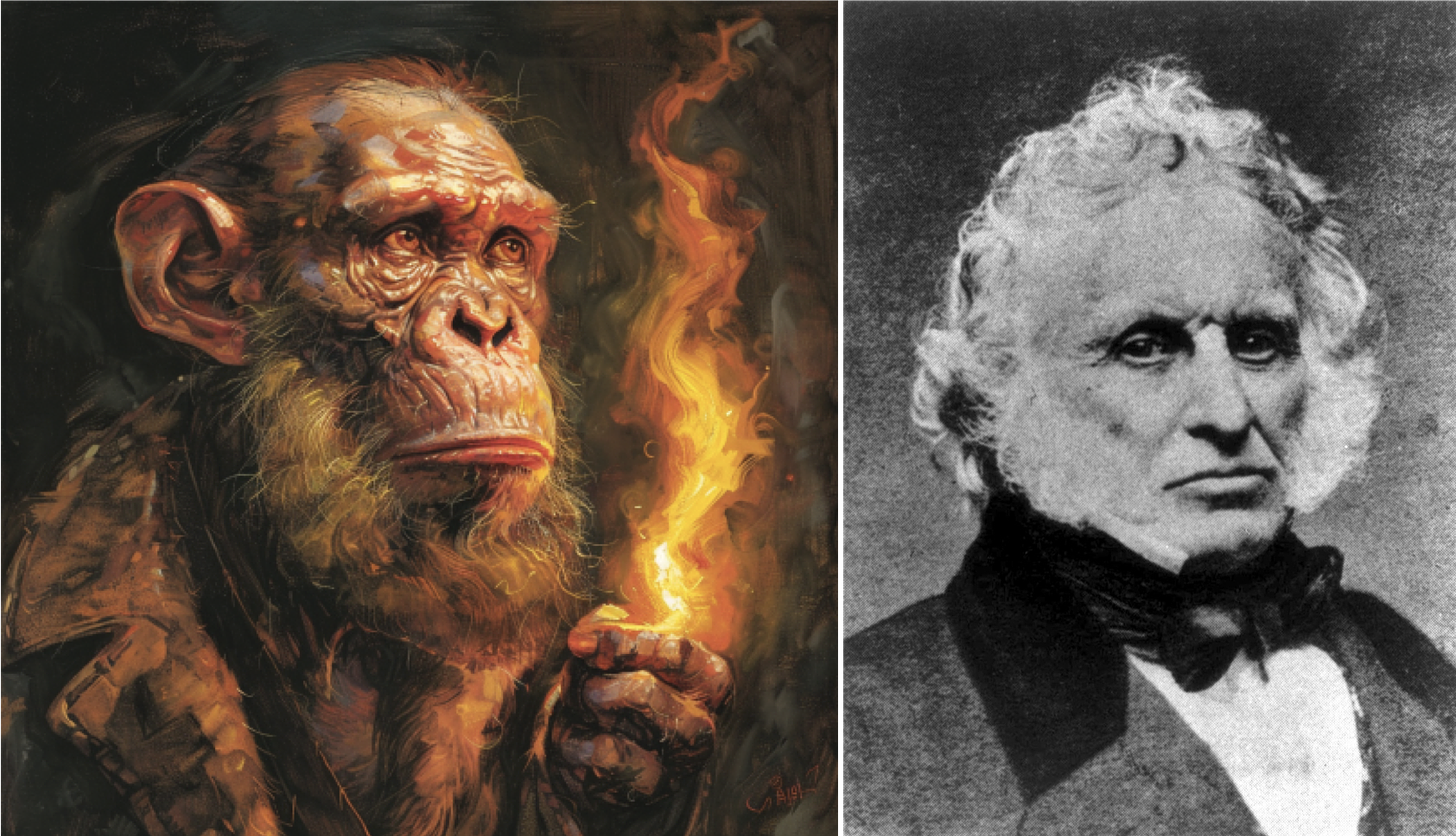

The credit for bringing this peculiar commercial venture to life largely falls at the feet of a single individual - an American by the name of Frederic Tudor.

Born into an illustrious Boston family in 1783, at the age of 22 Frederic Tudor would become obsessed with the idea that a fortune could be built around the export of Boston’s frozen assets to lands that were bereft of ‘white gold’. If he was still around today, he’d probably have his face perpetually splashed across the pages of every tech and business publication in the world, celebrated as the type of relentless founder that reshapes the world in his own image.

Tudor spent almost 60 years of his life solving the puzzle of the ice trade. Key to his success were figuring out how to efficiently harvest the ‘ice crops’ on New England lakes, and how to insulate ships to safely carry his precious cargo to faraway lands. Arguably his greatest impact was in engendering the love of cold air, cold drinks, and cold things into people that had literally never seen ice until his ships landed on their shores. If you’re reading this right now sitting in an air conditioned room in a hot country while sipping on an iced latte, you’ve been the victim of a 19th century propaganda campaign. Sorry to break it to you.

Because his initial customers in the tropics tended to be colonial rulers and the local noblesse, ice became the ultimate 19th century flex at restaurants, bars, hotels and dinner parties. In Company-ruled India, you could make the reasonable claim that ice was one of India’s first ever luxury consumer products.

By the end of his life, Tudor had convinced the world of the virtues of refrigeration. Because of his efforts, ice went from a luxury to a commodity to a necessity for most of humanity. To reach that point, however, he had to outlast the mockery and contempt of everyone around him who thought he was insane for trying to make a profit from the sale of frozen water. His defiant philosophy was “Let those who win laugh”, punctuated by his eventual status as one of the first millionaires in independent America. Through a mix of audacity, resourcefulness, and endurance, he would eventually be coronated as Boston’s ‘Ice King’.

The coolest part of examining what now seems like a primitive trade in a primitive time, is not the realisation that things have changed so much, but rather that they haven’t changed much at all. The tactics that Tudor used to build his business, prime his customers, battle his competition, and market his products, are as relevant today as they were more than 200 years ago. His documentation of the highs and lows of entrepreneurship, of the struggles inherent in doing something hard - in doing something that’s never been done before - will resonate with anyone attempting to do the same in 2024.

His story is the ultimate proof of the late Charlie Munger’s maxim that “learning from history is a form of leverage”. It’s the kind of story we want to preserve on the shelves of Tigerfeathers.

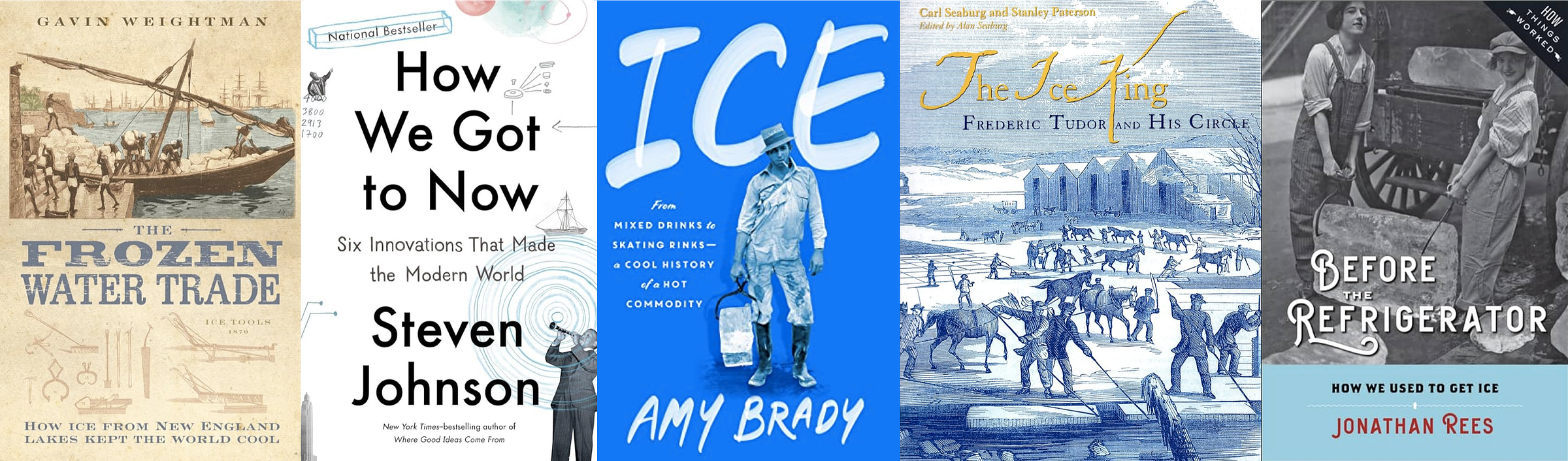

You might assume that much of Frederic’s story has been lost to history. Luckily for us, he maintained the 19th century equivalent of a Twitter account i.e. he had a diary. He called it The Ice House Diary, and meticulously recorded in it the events of his life and business for 33 years. It has served as the main fodder for two excellent books - The Frozen Water Trade and The Ice King: Frederic Tudor and His Circle. Along with a 1991 essay titled The Nineteenth-Century Indo-American Ice Trade: An Hyperborean Epic, these three documents serve as the primary source material for the essay you’re about to read.

Much of the India portion of this story has been scattered in the memoirs and travelogues of Brits who were stationed in colonial India during this time. These writings paint a vivid picture of life in India in the 19th century, and of the socioeconomic ripple caused by the introduction of Tudor’s ice into colonial Indian society.

So all together, today’s piece is a compilation of my notes from a month buried in the ice (trade). It has three main sections:

Frederic Tudor’s background and life story

The intricacies of his ice trade

Vignettes from the 1833 arrival of ice in India

Truth be told, I didn’t have to do much to add flavour to the tale of Frederic Tudor. My job was mainly to assimilate the scraps of narrative parchment from different places, and hope that together they assume the form of a coherent Tigerfeathers essay.

As always, let us know what you think in the comments or by replying to this email. Same drill if you want to partner with us to sponsor a future edition of the newsletter.

And with that, our story begins.

"The frost covers the windows, the wheels creak, the boys run, winter rules, & $50,000 worth of Ice floats for me upon Fresh Pond."

There is unemployable, and then there’s Frederic Tudor.

Frederic Tudor was hopelessly, resoundingly unemployable.

Not unemployable in a way that a vagabond is unemployable, but unemployable in the way that a hummingbird is unemployable. He was afflicted by the tinkerer’s curse - incapable of sitting still - his brain preoccupied by an endless conveyor belt of schemes and dreams.

Even as he fought to conquer the realm of frozen water, he would, at various points in his life, become embroiled in an assortment of ventures to:

build a faster ship to aid the American war effort against Britain in 1812

mine for coal on coastal islands in the North-East of the United States

design a pump to siphon water from the holds of vessels

mine for lead to manufacture graphite crucibles

start a saltworks business at his seaside holiday estate

speculate on the price of coffee

…among others, with varying degrees of success ranging from moderate to catastrophic. So, in hindsight, when he announced to the world at the age of twenty-two that ‘he could make money out of a commodity other New Englanders regarded as worthless’, he shouldn’t have been surprised when his proclamation was greeted with laughter.

Origin of the Ice King

Outside of the Western world, it can be easy to forget that America and India share the same colonial lineage. Fifty united states were once thirteen American colonies that declared their independence from Britain in the late 18th century.

American independence was formally ratified by the British Crown on 4 September 1783. A day later, Frederic Tudor was born. His life would be intimately shaped by the unique opportunities and challenges inherent in the embryonic years of a new sovereign state.

Frederic was one of six children - four boys and two girls - born to his parents. Unlike his brothers, he spurned the chance to attend Harvard, believing it to be a waste of time. Instead, at 13 years old he dropped out of school to serve as an apprentice in a local trading business. He believed that a practical commercial eduction would serve him far better in life than a ‘lazy’ stint at university.

Frederic’s father - William ‘Judge’ Tudor - had also studied law at Harvard and had his own legal practice in Boston. He had served as colonel and Judge-Advocate in the Continental army of George Washington. As an elected representative to the Massachusetts state legislature, his name carried considerable weight in Boston society.

Frederic’s grandfather - John Tudor - had been a self-made baker and merchant. He had amassed a not-insignificant fortune by the end of his days. In 1794, when Frederic was eleven, his grandfather died, leaving the family $40,000 in cash and other assets. Chief amongst these was a rugged 100-acre farm located a few miles inland from Boston called Rockwood (said to be a portmanteau of the two major resources found there - rocks and woods).

Frederic’s father would opt out of his legal business on the receipt of his inheritance. His plan was to live out the remainder of his days as a ‘landed gentleman’ of Boston - engaged in international travel, socialising and general merrymaking. The Tudors grew to embody the kind of wealthy, influential, politically connected family that would later be grouped under the moniker of ‘Boston Brahmins’ to denote their aristocratic position in Massachusetts society. (The evaporation of their wealth would be the engine that ultimately fuelled Frederic’s maniacal pursuit of success).

It was at their Rockwood estate where, amidst the crags and foliage, Frederic would chance upon the opportunity to harvest the most lucrative crop on the property.

Eureka

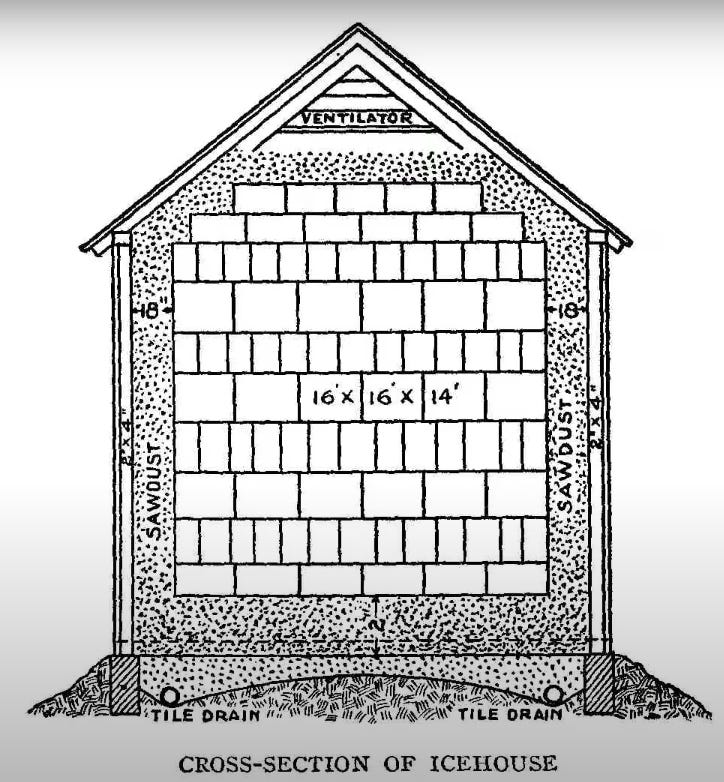

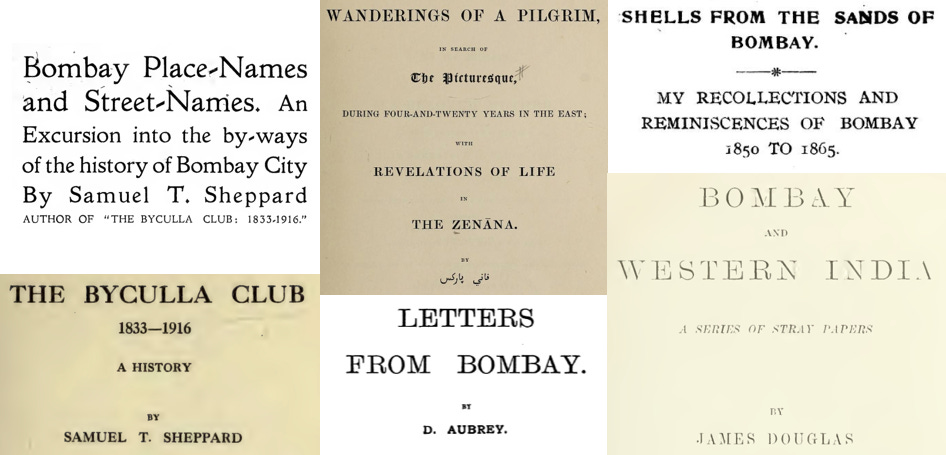

In the 18th century it was customary for wealthy families in Britain and New England (where winters were fierce) to have ‘ice houses’ on their countryside properties. These were commonly structures of lumber, brick or stone, mostly underground, that were used to store ice for consumption at home.

Natural ice would be cut from local ponds and lakes during winter and packed in these structures with insulating material like hay and straw. The ice houses would then be sealed off for months. This would allow the ice to last year-round, meaning wealthy families could enjoy luxuries like ice cream and cold drinks whenever they wanted.

The Tudors were one such family.

In the summer of 1805, Rockwood played host to a picnic to celebrate the nuptials of Frederic’s sister Emma with another Bostonian of good standing - Robert H. Gardiner. While sipping cocktails flush with crystal clear ice from their pond at Rockwood, Frederic’s older brother William made an off-hand remark suggesting that people living in the searing islands of the Caribbean would probably pay a fortune to access the same frozen luxury that the Tudors enjoyed for free.

Much like the crown of Archimedes or the apple of Newton, his brother’s chilled beverage was Frederic Tudor’s implement of divine epiphany. It would change the course of his life.

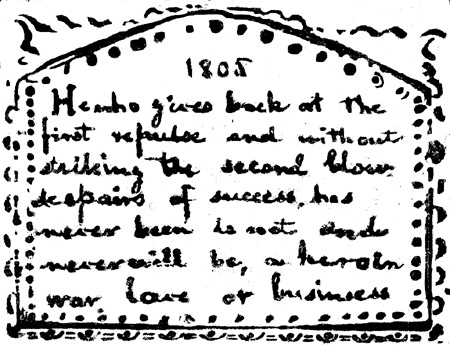

Even though William had only been joking, the idea seized Frederic’s brain like a virus. He had - what would be described in startup circles today as - a bias for action. He would soon convince William of the merits of this idea. Around this time Frederic purchased for himself a leather-bound farmer’s almanac and christened it The Ice House Diary. On the opening cover he drew a crude sketch of the Rockwood ice house along the border.

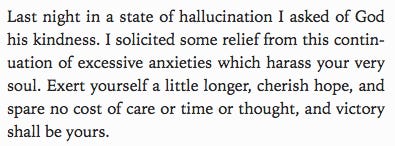

Several years later, after he’d been humbled, beaten, and broken by his entrepreneurial struggle, he would add the scrawl of text you see in the image above. It would serve as a reminder and a rallying cry that would come to define his stubborn pursuit of victory. It reads:

"He who gives back at the first repulse and without striking the second blow, despairs of success has never been, is not, and never will be a hero in war, love, or business."

Presently, he began to put his plan in motion.

NIce Trade

On 1st August 1805, Frederic would cement his intention with the first entry in his diary. He wrote:

“Plan etc for transporting Ice to Tropical Climates. Boston Augst 1st 1805

William and myself have this day determined to get together what property we have and embark in the undertaking of carrying ice to the West Indies the ensuing winter.”

He wasn’t kidding. Frederic was all in. He would scrape together whatever funds he had, and borrowed the rest, because he was convinced that his plan was foolproof. This brand of brazen confidence was necessary to surf the trials of a venture as “absurd” as the ice trade. But this same hubris would also condemn him to almost a half-century of indebtedness, where he was arrested thrice and went to jail twice at the behest of his frustrated creditors.

In 1805, the feasibility of his plan was challenged by the fact that no one in history had ever transported ice at the scale or the distance that he was envisioning. Outside of a handful of soaring mountain ranges, ice had scarcely even been seen by human eyes in lands close to the equator (like the West Indies).

Frederic’s assuredness was based on the conviction that ‘people living in tropical climates would pay a good price for ice if they could get it.’ He outlined this thesis in a letter to an associate of his father (and then US Senator) Harrison Gray Otis, writing:

Frederic had himself viscerally felt this need a few years prior when accompanying his brother John on a trip to Havana (Cuba) and Charleston (South Carolina) in 1801. The heat was so unbearable that it had their “tongues hanging out”. He recalled how he would have given anything for a shard of relief from their ice house at Rockwood.

He was also emboldened by other nuggets of information. He had heard tales of an American sea-captain that had transported ice from Norway to London, making a killing in the process. There had been rumours of ice-cream having survived the journey from England to Trinidad packed in pots of earth and sand. There had even been instances of ice crystals being found on timber boards shipped to the West Indies from New England.

Frederic had also personally gone to examine ice houses in New York that had been constructed overground. Coupled with the fact that the ice stored at Rockwood would last nearly all year round, he didn’t think it was unreasonable to believe that ice (properly insulated) could easily survive the fortnight-long sea voyage from Boston to the Caribbean.

As it turned out, the port of origin for this voyage proved more important than the destination.

Shipping out from Boston

Much like how a heady mix of geography, proximity, and ecology made places like Darjeeling and Kerala the hotbeds of the colonial tea and spice trades, the same factors would propel Boston to the undisputed forefront of the ice trade in the 19th century.

The state of Massachusetts was located in a temperate band on the Eastern shore of the Atlantic ocean, which meant there was an abundance of pure ice that could be cut from the countless spring-fed lakes, rivers and ponds that dotted the state. New England ice was said to be free of salt, sediment or oxygen bubbles. The ice was crystal clear, so clear that you could even read a newspaper through it.

Winters in the North East were no joke either. Water bodies would freeze up to a depth of 18 inches, where the ice was thick enough to bear the weight of an entire carnival of horses, workers, wagons, tools, and ice houses devoted to cutting and harvesting the ‘fresh crop’ every season.

The city of Boston itself was perfectly positioned too. By the start of the 1800s it was the leading port in the United States. This made it the main destination for ships from the southern states of America carrying raw cotton to the mills on the outskirts of Massachusetts. It was also the chief landing spot for Yankee merchants bringing back exotic goods from exotic lands for sale in America or re-sale in other parts of the world.

The problem, was that Boston didn’t have anything to offer in return. It didn’t have the climate, the soil, or the terrain to grow anything exciting. Its main exports - fish, furs, and lumber - typically wouldn’t move the needle in places like the American south, the tropical Caribbean, or the colonial East. All it had going for it was its location.

And that was good enough.

The Brig Economy

Long before the likes of Airbnb and Uber figured out a way to build businesses around spare economic capacity (apartments and cars), Frederic Tudor capitalised on another ‘wasted’ economic asset that was apparently invisible to everyone else - i.e. vacant space in the holds of trading ships.

Because Boston couldn’t offer much by way of outbound goods, American ships often left the Atlantic with empty holds, which left ship owners to reckon with two major problems:

1. They would often have to operate at a loss, because they weren’t receiving any freight charges for goods carried on their outward journeys

2. They had to resort to filling their holds with bulky material like sand and rocks (which needed to be dredged out of the bay), using these as ballast to prevent their ships from becoming unstable or imbalanced

Frederic saw this as an opportunity. He offered to pay these ship owners a small freight charge, in exchange for transporting his ice in their cargo. For them, even a relatively tiny payment was still a worthwhile financial incentive vs collecting nothing at all. The ice would also double as a ballast in their outward journeys, obviating the need to scrounge for heavy, worthless substances just for a single leg of their trips.

Frederic had found a way to exploit Boston’s apparent lack of tradeable commodities. He had turned lemons into (iced) lemonade.

This bit of logistical alchemy was arguably the single greatest catalyst that allowed the ice trade to flourish. It’s what made ice an attractive commodity for American ship owners, particularly those engaged in trade with faraway tropical territories that had no use for Boston’s homegrown exports. The cheap cost of transport allowed Frederic to always keep the price of his ice low for his final customers, which is what ultimately led to the ubiquity of ice consumption around the world.

Therein lay the real magic of ice as a commercial venture. Though it might have been crazy to think that ice could survive the 2,000 mile trip to the West Indies (and eventually several multiples of that), at its core the economics of the ice business were always sound:

The ice itself was free, and abundantly available

The insulating material - mainly sawdust and wood shavings - were a waste by-product of local timber mills, and also cheaply available

The transport costs weren’t prohibitive (because of the ballast arbitrage)

And the labour used to cut and move the ice was primarily made up of farmers and workers that were looking for temporary employment in the winter months

Frederic knew he didn’t have to worry about either the demand side or supply side of the equation. His task was to figure out how to navigate the perilous path between the two.

It was always said that “Yankee merchants had a sharp eye for other nations’ goods which they bought and sold as their ships scoured the world for bargains.” Given the apparently favourable calculus of the ice trade, Frederic always thought it curious that “even the shrewd merchants of Massachusetts had failed to realise that each winter a local product of dazzlingly high quality was left to dissolve away each spring, while in the tropical islands of the West Indies and the plantation states of southern America it would be worth its weight in gold.”

That gold would not be easily mined.

A Slippery Start

Even though the ice trade would be respected as a legitimate commercial enterprise by the end of the century, in late 1805, before the world had been introduced to artificial refrigeration, it was still a ludicrous proposition. It made Frederic a magnet for the naked scorn of Boston society. Robert Gardiner, Frederic’s brother-in-law and staunchest supporter, wrote at the time that:

But Frederic was undeterred. He saw the ice trade as his path to becoming “inevitably and unavoidably rich”. His approach to dealing with the mockery of his countrymen was to “put all their opinion at a non plus… I walked & bowed & smiled & talked like other men when they feel within them that they stand firm and need neither the assistance, the good wishes or money of anyone.”

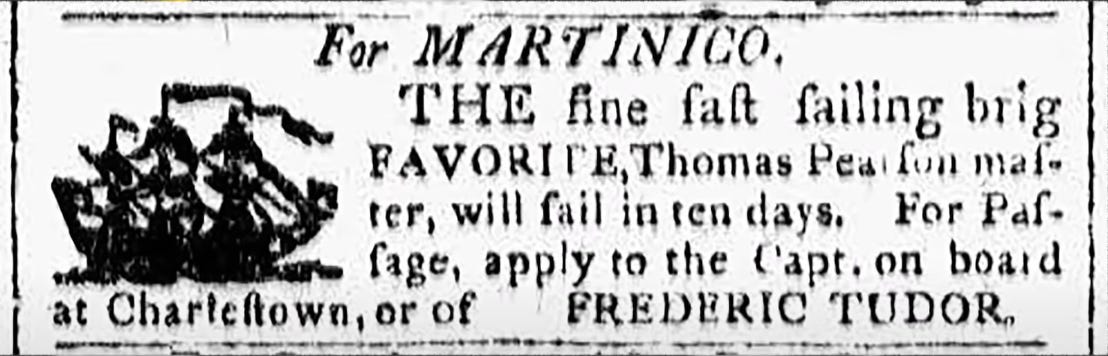

He had already earmarked the island of Martinique, part of the French West Indies, as the first bet for his venture. Martinique at the time was full of sweltering colonial expats. Its principal town - St. Pierre - had a population of 30,000, and a popular ‘Tivoli’ pleasure garden that could serve as a tactical site for distribution. In the autumn of 1805 he commenced with operations.

His first move was to lobby the US congress to secure a monopoly over the American ice trade. His rationale was that an officially sanctioned monopoly would inoculate him from competition, which he anticipated would follow in droves once other Boston merchants heard of his plan. Frederic’s application was rebuffed. But as it turned out, he didn’t have to worry about other contenders at all. When the news of his venture leaked out, he wasn’t met with legions of eager competitors but by waves of widespread ridicule. This was the headline in the Boston Gazette that greeted the news of his first shipment of ice to the West Indies:

Though the US had rejected his argument for a monopoly, this wouldn’t preclude him from trying to secure exclusive rights to sell ice in every new market that he descended on. It would become a key part of his frozen-water playbook. For his first shipment to Martinique too, he counted on being able to lobby local bureaucrats or their colonial rulers for the same exclusive privilege, even if the US wouldn’t acquiesce to his request.

By late 1805, in addition to his brother William, Frederic had also roped in his cousin James Savage into his venture. Both William and James departed for Martinique in November with instructions from Frederic (who would join them later on along with the cargo of ice). The duo’s tasks were mainly to:

- secure exclusive commercial rights from local officials (by bribing them with gifts of ice);

- find a suitable site for an ice house and finish construction by the time the ice arrived;

- secure advance orders for ice from local residents, and hire an agent who could handle sales

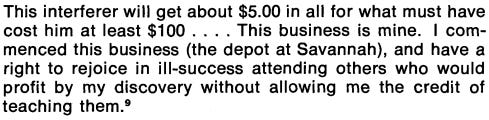

Their mission was largely unsuccessful. James would be stricken by yellow fever soon after arrival, restricting his usefulness. William did eventually succeed in securing a monopoly in Martinique (with generous doling out of ice and gold), but the failure to erect an ice house meant that Frederic had to sell ice directly from his ship. Their shortcomings caused the venture to begin on inauspicious footing. For Frederic, a man of uncommon standards of effort and determination, these failings were unacceptable. He would later confide to himself that:

This was slightly unfair, considering that his own efforts in Martinique hadn’t met with much luck either.

Proof of Concept

While William and James left to lay the groundwork in the West Indies, Frederic prepared the logistics for the world’s first (deliberate) international shipment of frozen water. Contrary to how sophisticated and efficient the cutting and harvesting process would later become, this first crop of ice was hacked and sawn out by manpower mostly from the Tudors’ pond at Rockwood, and transported in wagons to Boston harbour.

Ship owners at the time regarded Frederic’s plan as ridiculous. He couldn’t find a vessel that would take his ice as cargo. No one wanted to take the risk of having a ship-full of slush that ruined both their vessel as well as any accompanying merchandise. It meant he had to stump up his own capital (the vast majority of it) to purchase his own brig - the Favorite - which he did for $4750. The silver lining was that he was free to then modify the ship’s hold with a lining of timber that acted as a crude form of insulation from the outside air. On 10 February 1805, the Favorite departed for Martinique with 130 tons of ice.

Frederic would claim that his ice survived the 20-day journey in “perfect condition”. But selling ice in the tropics proved to be a far trickier proposition than he had envisioned.

William and James had already sailed onwards to try their luck in the British West Indian islands of Antigua, Barbados and Jamaica, leaving Frederic a letter warning him that sales in Martinique would be tough. Moreover, their failure to erect a local ice house prevented him from landing his cargo. He was confined to the harbour to sell chunks of ice directly from his ship. This meant that every time he would open the hold to take out ice for customers, the sultry Caribbean air would rush in, rapidly melting his wares.

Frederic had also taken pains to distribute ‘handbills’ (i.e. fliers) to advertise the historic arrival of his shipment. These aimed to educate local residents on how to properly treat, protect, and use the ice. Despite this, he was left frustrated by the perceived ignorance of his buyers, complaining to his brother-in-law that:

Although he managed to sell $50 worth of ice in the first two days (charging 16 cents for a pound), and $2,000 for the entirety of his trip, he estimated that the total loss from his first voyage tallied at somewhere between $3,000-$4,000. After several days of lukewarm sales, he ultimately cut his losses and swapped his remaining cargo for a hold-full of sugar from a local merchant.

On the outset, it appeared that Frederic’s naysayers had been right all along.

But Frederic had a ‘blind commitment’ to the venture. To him the Martinique experiment had only validated his thesis. It had proven that ice would survive a long journey by sea to a tropical island. It showed that a cargo full of ice wouldn’t damage a ship. It had proven that there was a market for ice. It also made it apparent that building a local ice house was a pre-requisite to having a smooth sales operation, something that would become the norm for him going forward.

Most of all, it hammered home the idea that Frederic would need to get creative in order to convey the utility of his product. His glistening mass of theoretically profitable produce wouldn’t just sell itself. Luckily, Martinique had already presented a solution for that conundrum too.

Making a Market 🍦

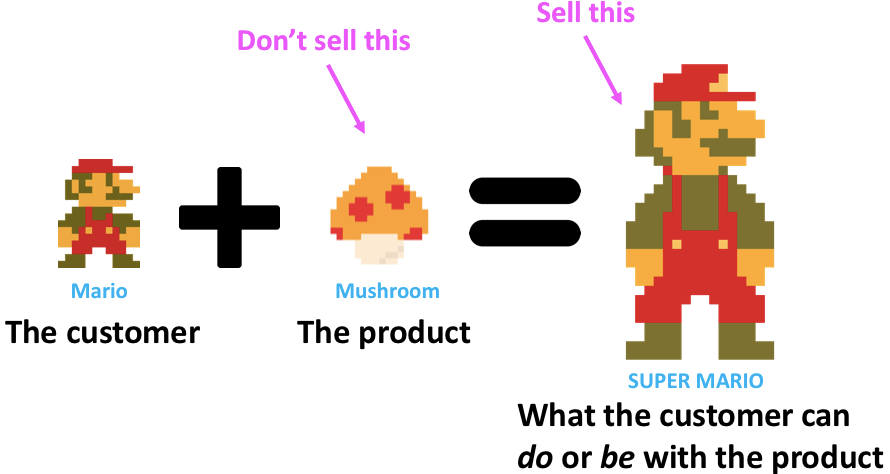

Don Valentine, the legendary founder of Sequoia Capital, once said about his investment philosophy that “Great markets make great companies…We’re never interested in creating markets – it’s too expensive. We’re interested in exploiting markets early.” He may have eventually come around to appreciating the economic virtues of the ice trade, but back then Frederic wouldn’t even have made it past the security desk at Sequoia HQ. When it came to the ice market, Frederic Tudor had to build it entirely himself - block by block.

As we’ve talked about already, there was no global frozen food and drink industry at the time. Ice hadn’t caught on as a palliative care solution or been proven as a preservative. There were no refrigerators or A/Cs or ice boxes. Outside of the colonial elite in the Caribbean, people regarded ice as just a thing that felt weirdly good in the heat. Frederic couldn’t rely on them figuring out its usefulness themselves. He had to show them, that it wasn’t about the ice itself, it was about what the ice allowed them to do.

Frederic had to create the markets he wished to dominate. In Martinique he kickstarted this process with the lowest hanging fruit. He brought out the belle of the ice ball - ice cream - for a soiree in Martinique’s most prominent public space.

This was a small win in a first battle that had yielded few causes of celebration. But for Frederic it was proof-of-concept. It was evidence that a market could be made. The incident even made an appearance in the local newspaper in St. Pierre:

Frederic would keep a clipping of the article as a keepsake in his diary, marking it as a pivotal step in his quest for glory. By the time his second shipment of ice left for Cuba a year later in 1807, his playbook had begun to take shape.

Show & Tell

While learning about the history of the ice trade, I was routinely surprised by how Frederic Tudor had pre-empted so many of the tactics that we today regard as textbook components of a modern marketing campaign.

The year after Martinique, in the second season of his venture, he placed considerable weight on product demonstration and product placement when introducing his merchandise to the people of Havana, Cuba. Frederic was savvy enough to realise that aside from solving the logistical challenge of ice delivery, he also needed to cultivate a ‘taste for cold’ amongst his potential consumers.

In 1807 he found that his main customers were cafe owners who were using the ice to make chilled drinks and ice cream. He realised early on that his best bet for success was to raise the fortunes of everyone else in his ‘value chain’ as well (‘only if they prospered would he’). The presence of a local ice house reduced the time pressure to get rid of his supply and gave him room to be creative with his promotional strategy.

He persuaded an ice cream man “to teach all the cooks in the city to make ice cream”, with the broader objective of helping his partners to use the ice profitably. Frederic made $6,000 over three consignments in his first Cuban season. Three years later in 1810, he generated his first profit from the venture (of a princely sum of $1,000), proudly writing that that season would forever remain “a monument of the advantage of steady perseverance in a project that is good in the main”.

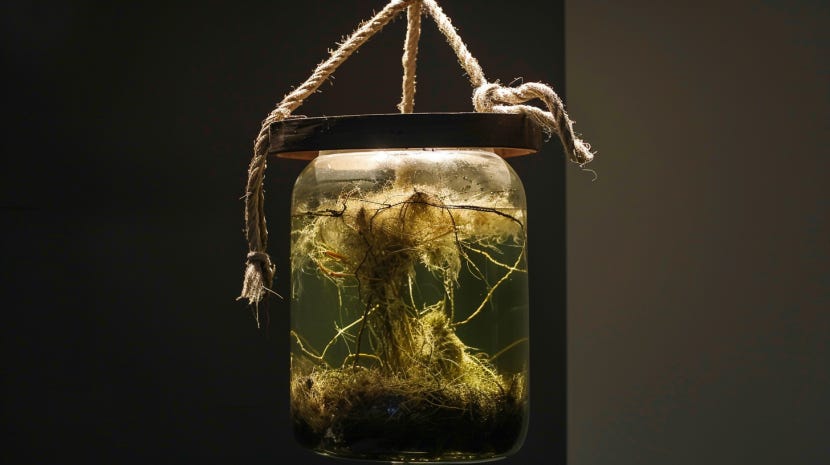

He continued to use Havana as a test bed for new marketing and distribution experiments. For instance, in 1816 he developed a proprietary ‘water-cooling jar’, describing it as “a jar of about 14 gallons suspended by ropes and surrounded with one thickness of dry sawdust two inches thick and another of dry moss of the same thickness with two covers one below the other with blanket and a crane with a cock to it to draw off the water.” It didn’t really ‘cool’ water per se, but kept chilled water cold enough for it to be sold by the glass over the course of a day. It was a clever way for him to commercialise the (clean) melt water that collected at the bottom of the ice house.

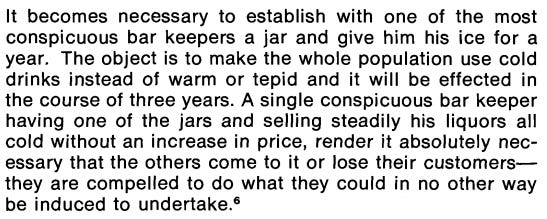

Even shrewder was how he employed this contraption in the market. In a remarkable bit of promotional nous, he saw the value both in visible product placement as well as ‘influencer’ marketing:

It’s no different from the marketing campaigns you’d see from modern FMCG brands. In fact, on an episode of David Senra’s Founders podcast about Dietrich Mateschitz (the founder of Red Bull), he brought up two 20th century variants of the same tricks employed by Tudor a century prior - Estée Lauder’s pioneering approach to sampling, and Red Bull giving out free cans of energy drink to bartenders and patrons at nightclubs.

Frederic recalled another instance of this ‘show-don’t-tell’ approach from his stint as a resident at a boarding house in sun-soaked Charleston (South Carolina):

Ultimately his objective was to inculcate an ‘ice addiction’ amongst his customers. That’s not hyperbole either. Frederic knew that his success rested on him being able to make ice a perennial necessity, rather than an occasional luxury. He spells this out most explicitly in an 1820 letter to his agent in St. Pierre:

It’s strange to think that cold water was once the subject of a marketing campaign. It speaks to the insane dedication to the cause exhibited by Frederic Tudor, who understood that even though the manufacturing of ice was free, it was another thing entirely to manufacture demand for it.

“Drink Spaniards and be cool that I, who have suffered so much in the cause, may be able to go home and keep myself warm.”

It makes you question how much of your tastes, and how much of our modern refrigerated culture, would have been different if not for the efforts of a single entrepreneur more than two centuries ago.

And this was all before he had even considered turning his gaze Eastward.

Before India

“Had I faultered all would have been lost. I thought for a moment I must sell my watch and escape home, abandon my Havana business, this also, and sink into utter despair.

…About this time I made a memorandum in my Ice book Diary "what signifies courage if it abandons us in our utmost need?" I made many other reflections (after a few wincings of weakness) on the dastardliness of despair. I put my shoulder to the wheel and after many a hard struggle I have rolled my waggon on.”“I have so willed it…”

- Frederic Tudor (14 April, 1817)

Frederic Tudor’s reign as the Ice King can be divided into two halves - before and after India. The first half was characterised by intense struggle, as he worked tirelessly to solve the confounding puzzle of the ice trade. For the best part of 28 years (from 1805 till 1833) he lurched between triumph and turmoil, bearing the full weight of not only launching a new startup but a new way of life for much of humanity.

Aside from the typical teething problems faced by young entrepreneurs, Frederic had to contend with other formidable exigencies like pirates, shipwrecks, privateers, trade embargoes, yellow fever, malaria, warm winters, corrupt ice-house keepers, impatient creditors, and Napoleon. In the midst of his strife, he lamented about the ice business that “It has cost me a great deal of trouble but I believe it will eventually repay me if I am able to carry it on.”

His writings paint him as a sort of Muskian figure with an insatiable appetite for action. He often used the surplus from one venture (however meagre) as an excuse to take a big swing at another venture (however risky). No sooner would he claw himself out of one debt-laden hole than he would find himself ensnared again.

There was never any inclination to take it easy or rest on his laurels.

“I have, indeed, no leisure of mind. It is surcharged with the business and purpose of life. For some years it has been a subject of lamentation to me that I have no leisure intellect, which I have a right to employ as I could wish.”

It was that same inability to sit still that separated him from his would-be competition. One of the quirks of the ice trade was that there was never anything inherently defensible about what Frederic was trying to do. The ice was available to anyone with access to a body of water in New England. By the 1810s merchants in Boston had even co-opted his ‘ballast’ trick, filling their holds with ice on their outward journeys to make a bit of extra cash at their destinations. Yet he was able to not only maintain his edge but fortify his position on top, to the point where he earned a reputation for being one of America’s first monopolists.

It helped that he had one rule: “never to be beaten”, but aside from having a near-limitless supply of motivational quotes, his ascendance is attributable to four main factors.

1. Ice-as-a-service

Contrary to other Boston merchants, Frederic never saw ice just as a superior form of ballast. He had a much bigger vision. To him, the ice trade wasn’t even about ice, it was about selling an appreciation for the cold that could then manifest in several commercial avatars.

As far back as 1816, he was running experiments with refrigerated fruit. He stored Cuban oranges in barrels in the Havana ice-house, and Baldwin apples from Boston in the holds of ice-carrying ships, to test if fruits would last longer in the cold. He concluded early on that the fruit business “must become an object of the first importance in the Ice business”. By 1820, he had even begun to find success even in the transporting of fresh fish preserved in ice to Savannah, Georgia. He had effectively preceded the ‘frozen food business by a hundred years’.

Frederic’s broader vision was to make an ice a permanent part of people’s routines - to make it a ubiquitous societal commodity. If you enjoy sipping on your summer iced latte today, you likely have him to thank for it. In fact, his trade would lead to several modern conventions we still adopt today, including this incredible bit of neologism courtesy of Amy Brady’s book on the history of Ice:

Frederic understood that the ubiquity and pervasiveness of ice was essential to ensuring a steady year-round demand. Also essential to ensuring steady year-round demand was steady year-round supply.

2. “Once you’re 10x better, you escape competition.” - Peter Thiel

Frederic spent decades tweaking each element of his ‘cold chain’ till it was fit for purpose.

‘From pond to ship was the scheme of Frederic’s fertile mind.’

- The Ice King: Frederic Tudor and His Circle‘He had a constellation of carpenters, agents, suppliers and ice-house keepers now, so the business could run itself provided everyone behaved honestly.’

- The Frozen Water Trade

Key to the success of his operation was his ice house. A well-designed ice house - as Boston elites knew - could guarantee that ice would be available all year round. If people knew that ice was available all year round, they could integrate it into their daily lives and routines without any concern that it would run out.

His idealised model featured a double-walled structure (made of lumber or brick) with the cavity stuffed with pulverised charcoal and sawdust to keep it dry; with ample sawdust and wood shavings packed around the ice as an insulator; a drain pipe to carry out the melt water; and an arched roof or dome to act as a ventilator to expel warm air.

Much like Bezos and his warehouses, or Michelangelo and his Sistine Chapel, Frederic’s ice house was his masterpiece. Much like Amazon’s mastery over its supply chain, a well functioning ice house at the point of sale is what ‘opened’ the rest of his business. It’s what gave him the flexibility to store his ice for the long term. Because he was operating at a level of efficiency that far exceeded his competitors, he could drop his ice prices in every market till he drove them out.

As the market for refrigeration and preservation began to display green shoots, he even took to selling fridge-like boxes called ‘Little Ice Houses’ in places like Charleston. These were probably closer to modern ice boxes than they were to modern fridges. They were small wooden containers with a metal lining that could hold three pounds of ice, which was enough to keep drinks, ice cream, and fruit in good condition for a day. The Little Ice Houses further entrenched Frederic’s product into people’s homes and spurred them to purchase regular daily allowances of ice via subscription (much like we do with milk today). It was equivalent to selling fanny packs at an opium den.

Wherever he could, Frederic made it easier for people to use his product.

In the hands of another entrepreneur, the ice trade may have been too unwieldy to wrangle. It helped that Frederic Tudor had:

- a compulsive obsession over the details (“to produce the most perfect results…attention to perpetual & perfect discipline, is necessary”)

- a thrifty disposition (“small expenses which occur every day amount to a great sum at the end of the year”)

- and an iron-fisted style of leadership (“It is absolutely necessary that I should be obeyed…I must be a dictator”)

But it also helped that…

3. He had help

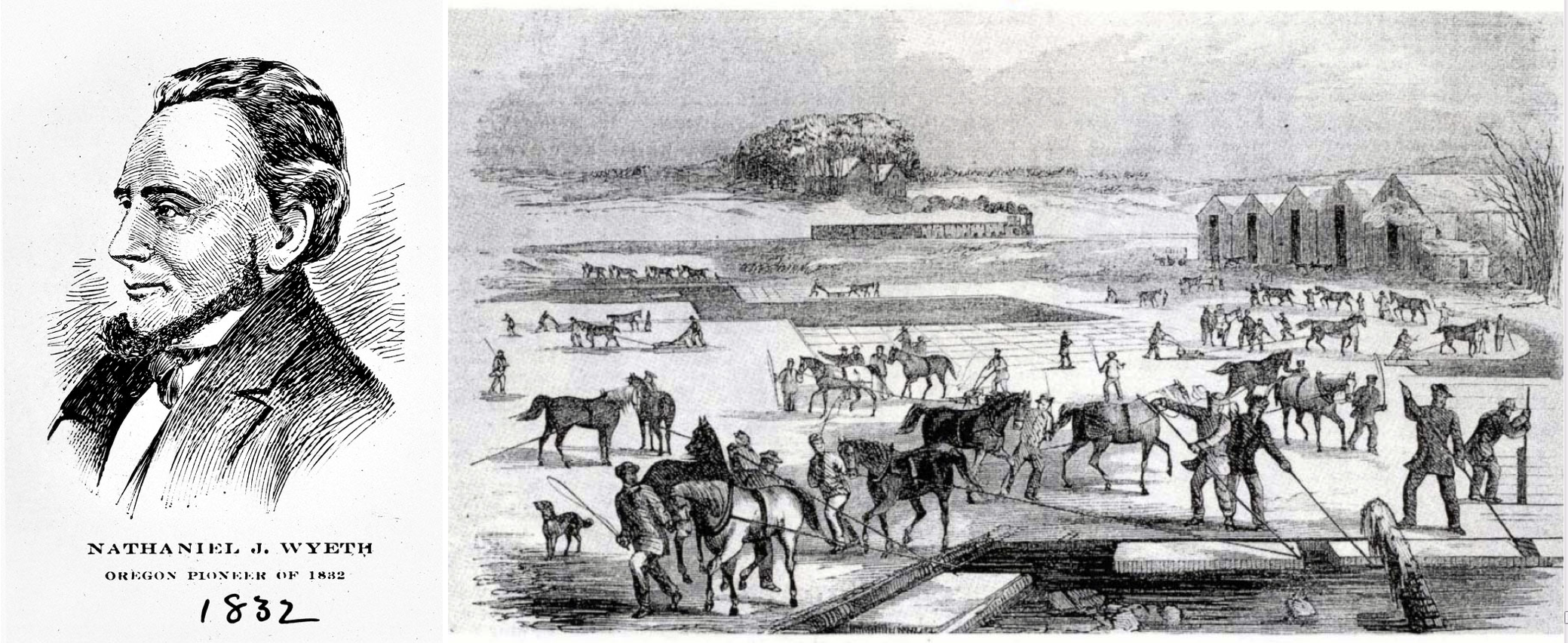

Nathaniel J. Wyeth was born in 1802, three years before the first entry in Frederic’s Ice House Diary. His father owned a resort on the shores of Fresh Pond in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which would become one of Frederic’s main sources of ice. Wyeth had grown up working for his father, a role that included the harvesting of ice for the comfort of guests staying at their property.

By the 1820s he had also begun supplying ice to several merchants shipping out of Boston as a way to keep himself busy and add an additional revenue stream to their operations. Like Frederic, he had a busy, obsessive mind that was constantly looking for ways to improve upon his trade. Frederic would resonate with this trait, writing that “For minds highly excited and in great activity there is no Sunday.”

Wyeth was the Steve Wozniak to Frederic’s Steve Jobs. He was a “schemer and inventor” of “singular excellence”, a man that Frederic considered a kindred spirit. He would develop several of the tools and techniques that would allow for the ‘mass production’ of commercial ice. His greatest contribution would be the invention of the double-bladed horse-drawn ice-plough. It changed everything.

Prior to this, the harvesting of ice was an expensive, time-consuming, labour-intensive process. Scores of men would have to scrape, hack, and cut the ice using saws and pick-axes. This would yield misshapen, uneven chunks that were inefficient to store and transport. These disorderly piles of ice would be riddled with air pockets, exposing more of the crop to the atmosphere and hastening the melting process.

Wyeth’s solution was to use horses to drag a double-bladed plough over a patch of ice, first vertically then horizontally, essentially making a grid of squares that could then be easily cut out using manpower. Workers would then gently float these even blocks through the water using grip-hooks, neatly piling them in nearby wagons or icehouses.

Aside from vastly reducing the time and effort involved in cutting the ice, this had the consequence of standardising the ice crop. The uniform blocks could be tightly packed together, vastly increasing the efficiency of Frederic’s supply chain, and materially reducing the quantity of ice lost to thawing.

Over the first half of the 19th century, Frederic and Wyeth would develop an entire range of tools to mechanise the ice trade, demonstrating that it could be harvested in huge quantities. Coupled with Frederic’s grand vision and his obsession with the details, this was a potent mix. Then came his motivation.

4. He had a ‘why’

Roughly a decade since his grandfather’s inheritance had been bequeathed to the family, the Tudors were, for all intents and purposes, destitute. A mix of profligate spending, wanton frolicking, and ill-advised land speculation had rendered their accounts bare.

By 1808 the family fortune had been squandered. Frederic, as the only real member with a commercial bent, took it upon himself to save them from impending poverty. Owing to his own debts and defeats in the early ice trade, he spent much of his 20s and 30s also in deep financial strife. By 1817 his father was compelled to take a job as the Secretary of State for Massachusetts to keep the lights on. It was an administrative role that had a nice title but a meagre salary. The family had lost their property and their prestige. His father would move to squalor housing in an unfashionable part of the city for the remainder of his days.

Francis Ford Coppola, legendary director of The Godfather, was fond of saying that “You can always understand the son by the story of his father. The story of the father is embedded in the son.” So it was for Frederic. He was deeply affected by the humiliation his father had to suffer, having grown up in prosperity that ended up in poverty. He made it his mission to redeem their lost wealth and status. That was his motivation, his reason for being.

‘Part of his whole desire for worldly success came from the anticipation of sharing it with his father’.

- The Ice King: Frederic Tudor and His Circle

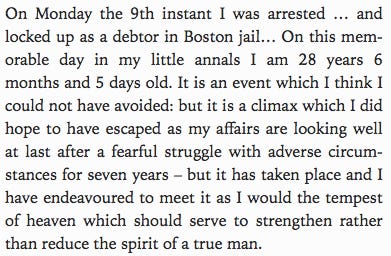

That’s what endowed him with a near-superhuman capacity for suffering. It’s what allowed him to keep going as he spent the better part of 20 years being “pursued by sheriffs to the very wharves”, for repayment of his debts. It’s what helped him retain his optimism during his third arrest and second stint in jail in March 1812, where he was able to soberly reflect on his predicament:

It’s what brought him back to sanity after suffering a stress-induced fever in 1821, which culminated in a full on nervous breakdown later in the year.

There was nothing pretty about his eventual success. He had no option but to succeed. The ice trade was his ticket to reclaiming his family’s honour. Profit was the surest path back to prestige.

“Those who have a 'why' to live, can bear with almost any 'how'.”

― Viktor E. Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning

It would take a quarter-century’s worth of yo-yo-ing between progress and peril, between princehood and pauperdom, till he could look back and take stock of what he had built. At the end of his ‘first innings’, he had fortified the major markets of the American south like Charleston, Savannah and New Orleans. He had a successful business in Havana, and bases in various islands of the Caribbean like Antigua, Barbados, and Jamaica.

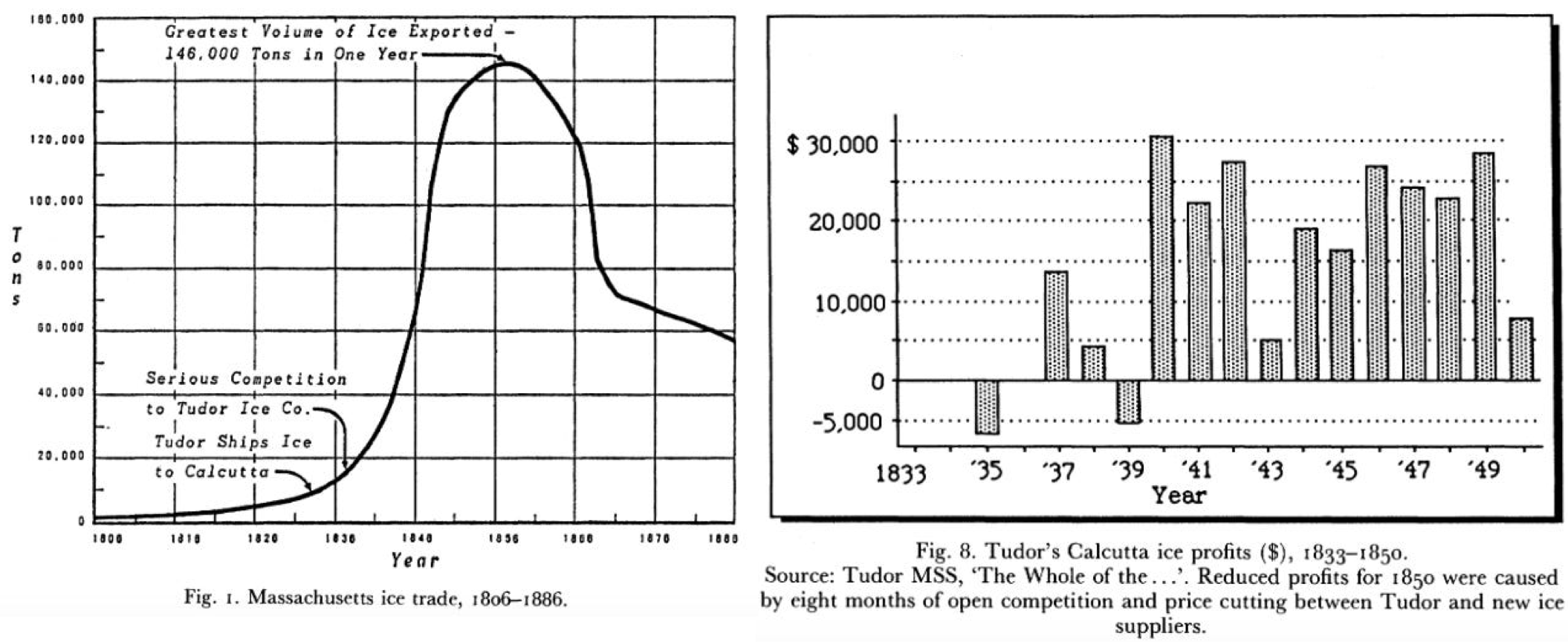

Through much trial and more error, he had ironed out his playbook. The ice trade had grown from ~100 tons shipped out of Boston in 1806, to 1,200 in 1816, and 4,000 in 1826.

“My income this year will be reduced full $12,000 but the coast is now cleared of interlopers, good and substantial foundations laid…The indications of results for next year are of the most satisfactory kind. The last has been a year of battle in which the elements have joined, with a host of miscreant men and adverse circumstances, to try the strength and firmness, the steadiness of resolution and bottom. All opposition has been met and overthrown - the field is won and now very little more than the shew of weapons and readiness for defense, I trust will be necessary. It has cost some wear and tear of muscle and nerves besides the above mentioned $12,000 in money. A dear victory: but probably thorough. If there are any unslain enemies, let them come out…”

- Frederic Tudor (29 September, 1826)

And at the edge of this conquered field, in 1833, the East Indies beckoned.

(Just) Before India

By 1833, Frederic Tudor had become a respected member of Boston’s mercantile community. It was widely acknowledged that he had made a credible contribution to the prosperity of the city. The ice trade was a respected line of business, considered at par with trades in commodities like silks, spices, or sugar. There were now several legitimate competitors to Frederic, but he was by far the market leader. More importantly, he was unanimously regarded as both the patron saint and the elder statesman of the industry.

So when Samuel Austin, a Boston merchant who was importing commodities from the British East Indies, realised he had a ‘ballast problem’ for his outward journey, he knew who to call (or who to exchange letters with…telephones hadn’t been invented yet). He approached Frederic in April 1833 with the idea to set up a joint venture to send ice to India. To Frederic, this had been a long time coming.

Part of his formula had been to seek out markets where the prevailing society was made up of a wealthy upper crust that would give up anything to escape the heat (eg: land owners in the American south that had gotten rich from their cotton plantations).

He would target the ruling class in these markets, often convincing them to stump up the funds to construct a local ice house on his behalf (and occasionally grant him a monopoly over ice sales). In their desperation for cold comfort, his patrons would even pay up for advance orders/subscriptions to guarantee their future allotment of ice (and guarantee him a recurring source of revenue). The consequence of this tactic was that ice became positioned in these societies as a luxury product. It would later filter into the lives of the wider public as supply regularised over time.

No demographic on Earth exemplified Frederic’s target market better than the colonial gentry in India. By the turn of the 19th century, the British had largely beaten back all their foes on the Subcontinent. But they hadn’t beaten the heat. Their accounts of the weather in India are dramatic AF.

Like, bro you could have just stayed in your home country lol?

To be sure, the British did have their methods of dealing with the heat. Houses were built with underground sittings rooms, raised verandahs and high ceilings to trap the cool breeze. It was common to hang wetted mats (called tatties) made of khus (a type of grass) across the frames of windows as a crude form of air conditioning. They slept in pyjamas made of gauze and drenched in cool water. Once the railways arrived, the luckiest of them made it a practice of escaping to temperate hill stations in the most unforgiving months of the year.

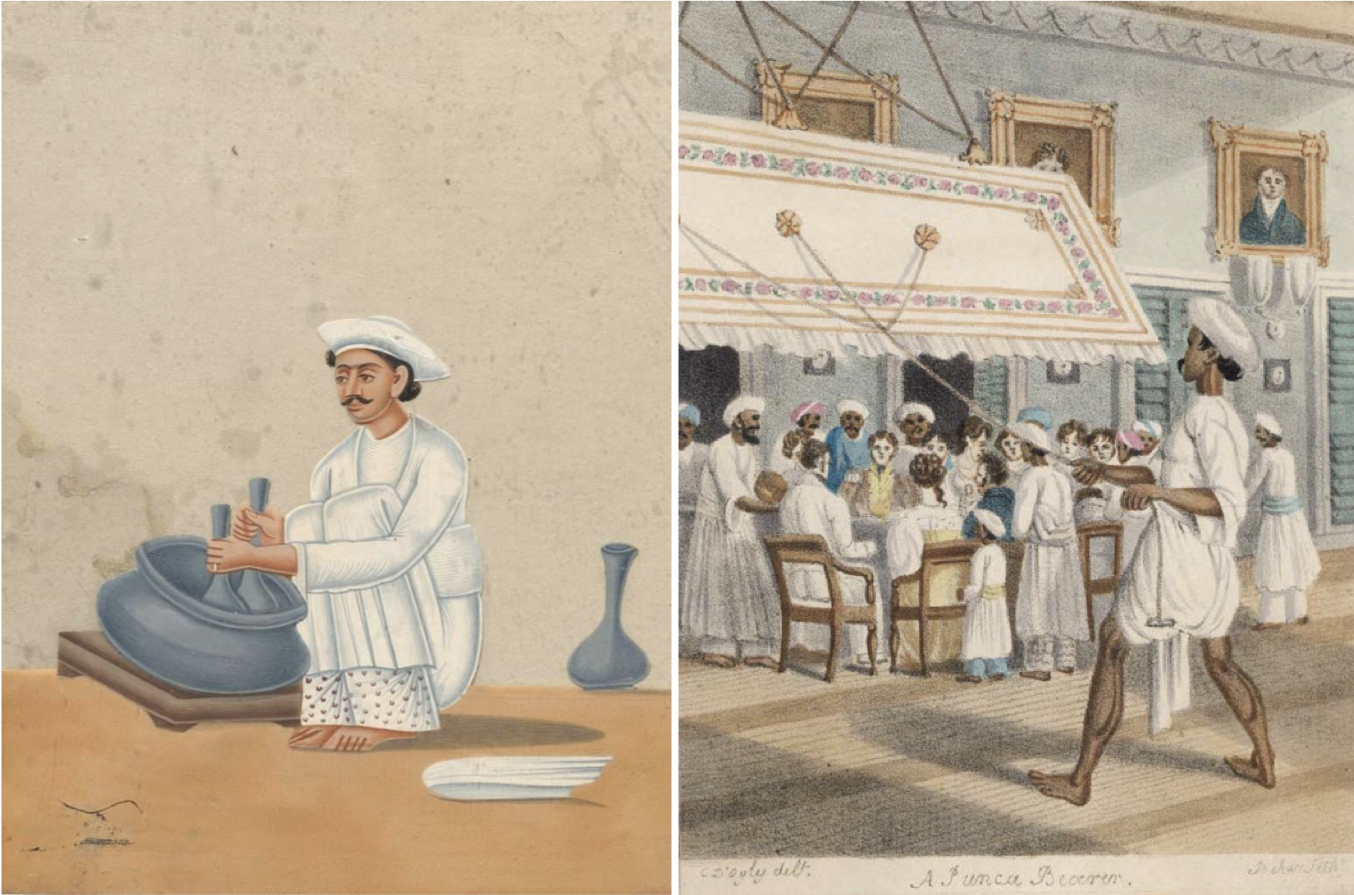

Their Indian subjects were roped in to provide relief too. There was a role for abdars, a member of the house staff whose sole job it was to stir naturally occurring saltpetre with water to create a cooling wet mixture for storing bottles of wine, water, and ale. Punkhawalas were also a fixture in colonial India. They were tasked with fanning the air in stuffy halls and bedrooms using ropes attached to giant cloth frames hung from the ceiling.

The British even had access to ice. It’s worth remembering here that ice itself is not foreign to India as a whole. The Himalayas that straddle the northern-most part of the Subcontinent aren’t starved of glaciers or snow.

In fact, it’s well documented that as far back as the 16th century, Mughal emperors Babur and Humayun would ‘import’ ice from Hindu Kush mountains on elephants and horseback, storing it in thick-walled containers and barafkhanas (ice houses) at their palaces in Delhi. They were fond of using shavings of ice to cool their drinks and make fruit-based sorbets. The Mughals inherited the Persian tradition of kulfi-making, where saffron and pistachios would be added to a condensed milk mixture. This would be packed into conical metal containers (sealed with dough) and buried in a slurry of ice and saltpetre for preservation. The word ‘kulfi’ comes from the Persian word for ‘covered cup’.

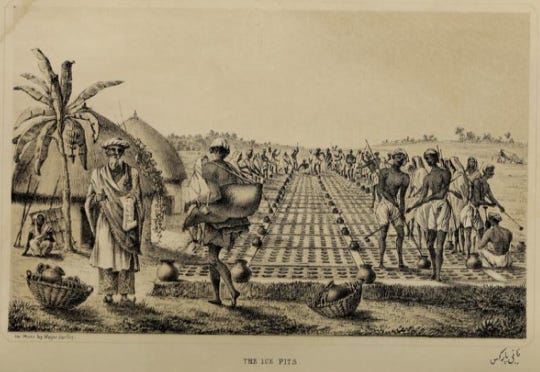

The British considered this approach impractical and expensive. The British in Calcutta especially - which was then the jewel of the East India Company - leveraged another hack to harvest ice themselves. About 40 km north of the city in the district of Chinsurah on the banks of the river Hooghly, they adopted a method of ‘making’ ice that had been an indigenous practice for centuries.

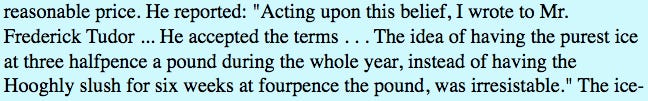

They would dig holes on a flat terrain and fill these with straw. Into these cavities would be placed small earthenware pots filled with water. In the winter season when the temperature dropped to near-freezing overnight, a thin film of ice would form at the surface of the water. This ice would be gathered before the morning and consolidated in underground pits, from which it could be accessed and sold through the summer months. This ice was substandard, not remotely close to the quality of Frederic’s “magical” product. It was appropriately referred to as ‘Hooghly slush’ - good for cooling containers or making ice cream but too dirty to be actually used inside a glass of water or a cocktail.

It was a slow and painful process (“two thousand labourers working on a huge acreage of land might collect twenty-five to thirty tons of ice in a night”), which meant it was expensive and inaccessible even to members of the British community. It was certainly out of reach for officials further south in Bombay and Madras. It made sense that officials of the Raj had already begun to think of a better solution. Longueville Clarke, a prominent barrister of the Supreme Court in Calcutta, had previously written to Frederic outlining their malaise (and promising that the inhabitants of Calcutta would build him an ice house if he could arrange a regular supply of ice at a fair price):

Frederic always knew that there was a lucrative market waiting for him in India. He had just never had the capital to undertake a voyage that risky. So when Samuel Austin approached him to partner up on an ice venture for India, he didn’t have to think too long. The joint venture would include a third partner named William Rogers, who would accompany their precious white cargo to Calcutta and handle sales on the ground.

A week after Samuel’s proposal, a ship - the Tuscany - had been engaged. Frederic meticulously fitted it out with extra insulation - extra layers of tan, lumber, and hay - to withstand the four months and 16,000 miles it would be at sea. He was so confident in his preparation that “if she does not carry her cargo safely to Calcutta and arrive with 2/3rds of it no ship ever will and the undertaking should be abandoned.”

He was also fully aware of the epic weight of history that had been thrust upon this voyage, writing to tell the captain of the ship that:

The India opportunity had reinvigorated his deep passion for the ice trade. It had also come at an auspicious time. From 1831 onwards Frederic had become embroiled in a speculation over coffee futures. In the manner of a gambling addict he had committed his entire wealth (and borrowed recklessly from others) to finance an ill-fated venture betting on the price of coffee going up. At one point, on paper, he owned 1/6th of all coffee consumed in the United States.

Despite the fact that his ice business was by now earning him $40,000 (~$1.4 million today) in profit every year, it was a drop in the ocean of debt he now found himself drowning in. It was entirely on brand for him to find success in one entrepreneurial venture while at the same time orchestrating his own downfall in another. India didn’t just represent a potential new territory to conquer. India was also potentially a ladder out of his financial hole.

So on 12 May 1833, courtesy of the fine sailing brig Tuscany, Frederic Tudor’s first shipment of ice departed for the port of Calcutta.

IceRaj

If you thought that serpentine lines of fanboys waiting outside the Apple store for the new iPhone was the epitome of commercial mania, you might re-evaluate your benchmark after reading about the hysteria that greeted the arrival of Tudor’s ice in Calcutta in September 1833.

It ranged from the outright disbelief of native onlookers:

To rapturous celebration from the colonial gentry:

“I will not talk of nectar or Elysium, but I will say that if there be a luxury here-I would point to the contents of our Ice-House, our 'Crystal Palace', and inscribe over its door some Moorc-ish couplet which might declare-[it is this, it is this!].

To a complete halt in civic proceedings, as documented by the local papers:

To outright sacrilege from the Anglo-Indian community:

In Bombay, Britons even began to substitute chilled drinking water for the conventional alcoholic beverages drunk in the evening after dinner, to the great amazement of Britons visiting from other stations.

And even casual poetry:

When it became clear that the rumour of ice arriving in India wasn’t a ‘hoax’ or a ‘joke’, the Tuscany’s progress up the Hooghly River became the subject of intense local interest. Frederic had estimated that 120 tons of the original 180 would survive. He wasn’t far off. The first East Indian shipment of ice made it to Calcutta with 100 ‘cakes of frosted silver’ on board.

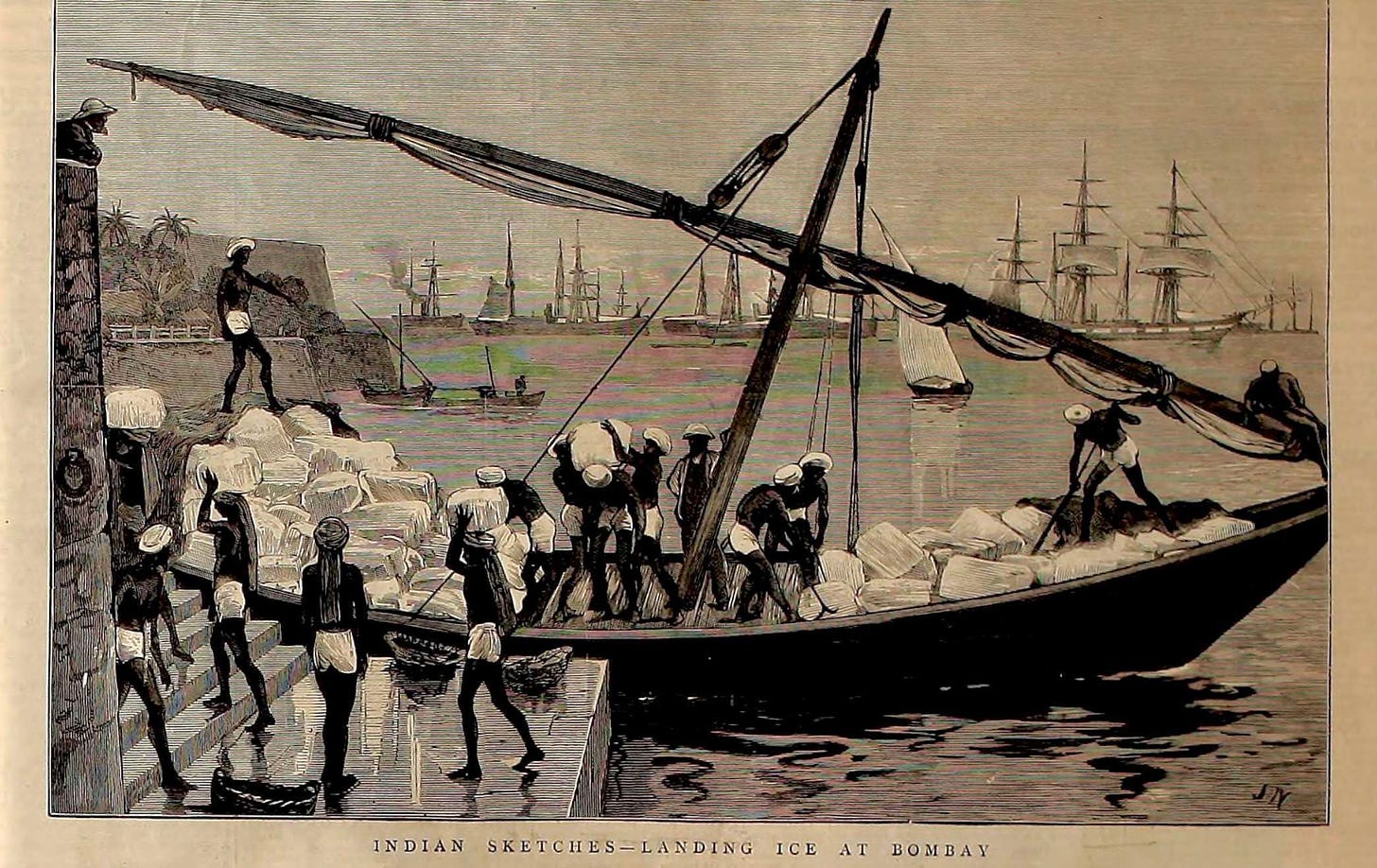

William Rogers - the third partner in the join venture - did his best to get the ice off the ship as fast as possible. He was aided by two special concessions that the local press had lobbied for (and won) - 1) that the ice should be declared duty free before it reached the wharf, so it could be unloaded straight away, and 2) that the normal prohibition around discharging cargoes at night should be lifted, to allow the ice to be unloaded in the cooler evening climate. (Frederic would be the beneficiary of several exceedingly generous concessions like these throughout his tenure supplying ice to India.)

The unloading process was a spectacle in itself. To hasten the off-boarding of the ice, Rogers orchestrated the construction of a makeshift bridge made up of boats and dinghies leading from the shore up to the ship in the harbour. Coolies and attendants of the British gentry could hustle up and down this walkway to collect their ice directly from the hold of the ship.

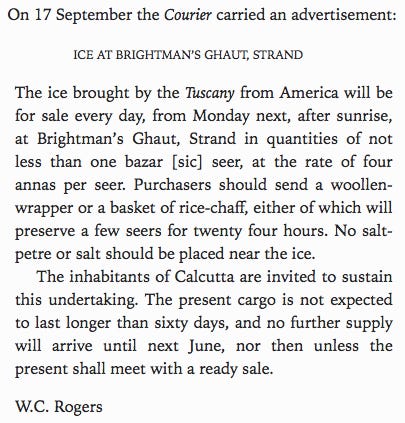

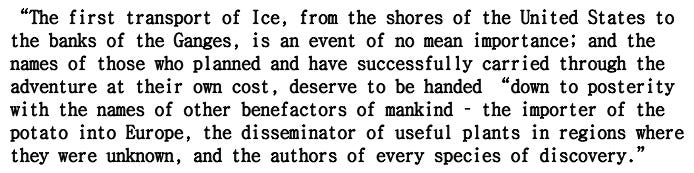

Frederic’s ice was a sensation. It marked a new chapter in the socioeconomic history of India, one where the twin technologies of refrigeration and preservation took root on the Subcontinent. The Calcutta Courier wrote that:

The British Governor General of India at the time - William Bentinck - published a letter in the India Gazette saluting the achievements of the venture. He even presented William Rogers with a commemorative silver gilt cup to celebrate the spirit of enterprise ‘which projected and successfully executed the first attempt to import a cargo of American ice into Calcutta’.

It was apparent from Day 1 that there was no going back to Hooghly slush.

Post-Ice

When all the scores were tallied up, Frederic had individually made $3,300 in profit from the first shipment of ice to India. The ice had sold well (out of a local godown that had been converted into a makeshift ice house). It lasted till December of that year. By the time his next cargo arrived in India in 1835, he had split from the joint venture and was operating solo.

In characteristic fashion, he drafted a lengthy letter to Lord Bentinck to make it clear that he was the real kingpin behind the ice trade, while also sullying the reputations of both Samuel Austin and William Rogers. He made the case for being awarded an exclusive privilege over the right to export ice from Boston to India. He claimed that if he was able to carry out the business without the distraction of competition then “India may have a delicious and high luxury, at a price little above the lowest necessaries of life”, where ice in India would become a ‘common and cheap gratification’. Considering how smitten they had been with the first batch that came in, it was an offer that was too good to pass up.

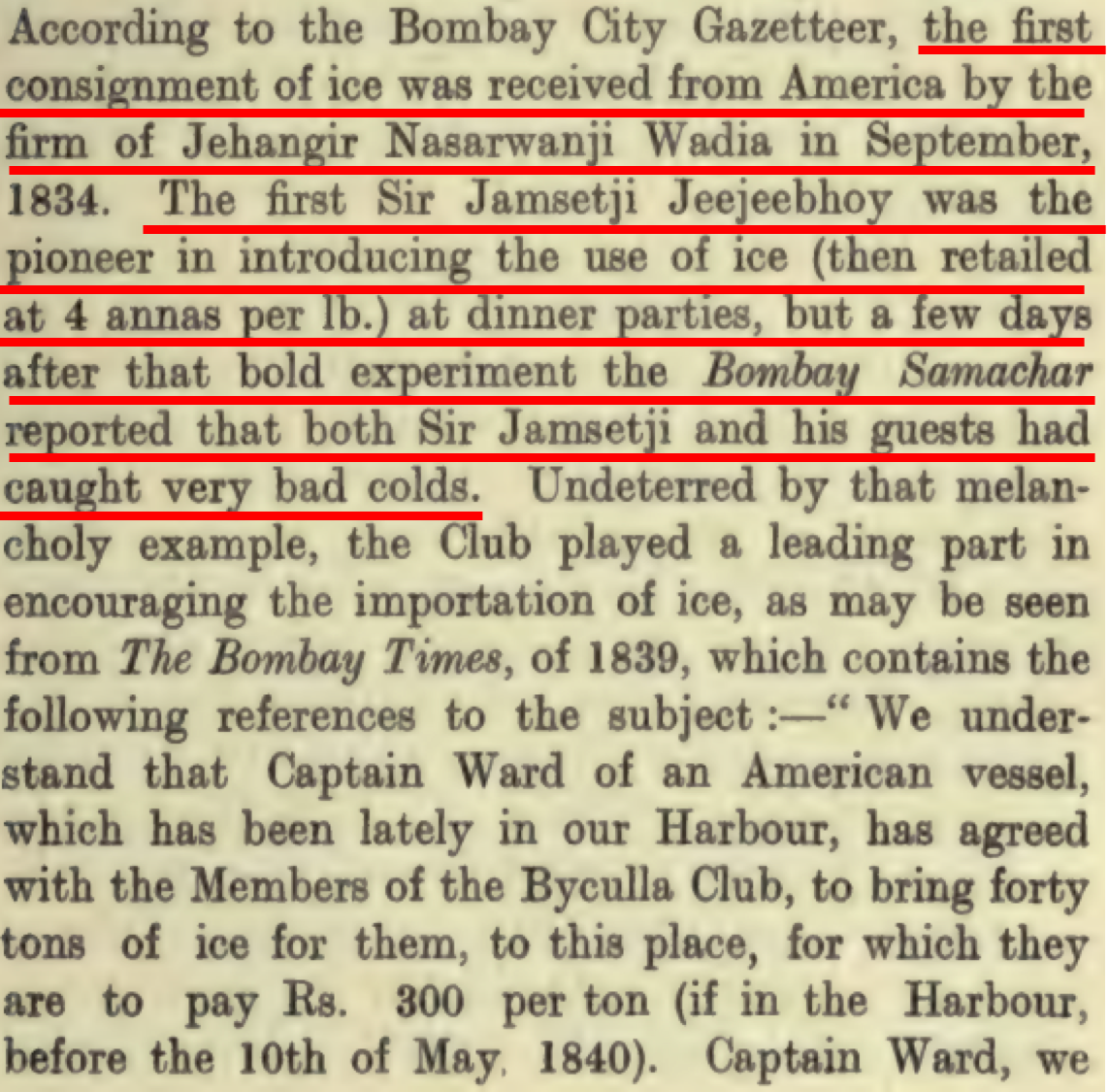

The British community in Calcutta took just three days from the arrival of the Tuscany to collect the subscriptions necessary to build an ice house. They wanted to go all out, eschewing the modest American design in favour of “a grand stone edifice more fitting to the ‘city of palaces’”. It wasn’t long before the gentry in the other Presidency towns of Bombay and Madras wanted in.

These cities similarly laid out the red carpet for him. The community in Bombay exempted him from standard import duties and provided his ships with prime location in the harbour. In Madras ice was only one of five total products on the duty-free list along with ‘bullion, coin, precious stones and pearls’.

While he awaited the construction of his ice houses, Frederic replayed his most successful strategies from America. Because the ice wastage was rapid and he needed to generate quick returns, he took to selling his ice at half-price, provided the local community would commit to a subscription of at least one ton of ice per day. In this way, he sold far more ice to far more people than he normally would have, and at the same time marked his product as the undisputed best in class.

For several years, Tudor’s ice was the trendiest product in colonial India. It was both a novelty and a luxury. Much like it was in America in the early-to-mid 19th century, it became a mark of status to have a dinner table brimming with generous helpings of glistening natural ice. No party was complete without it.

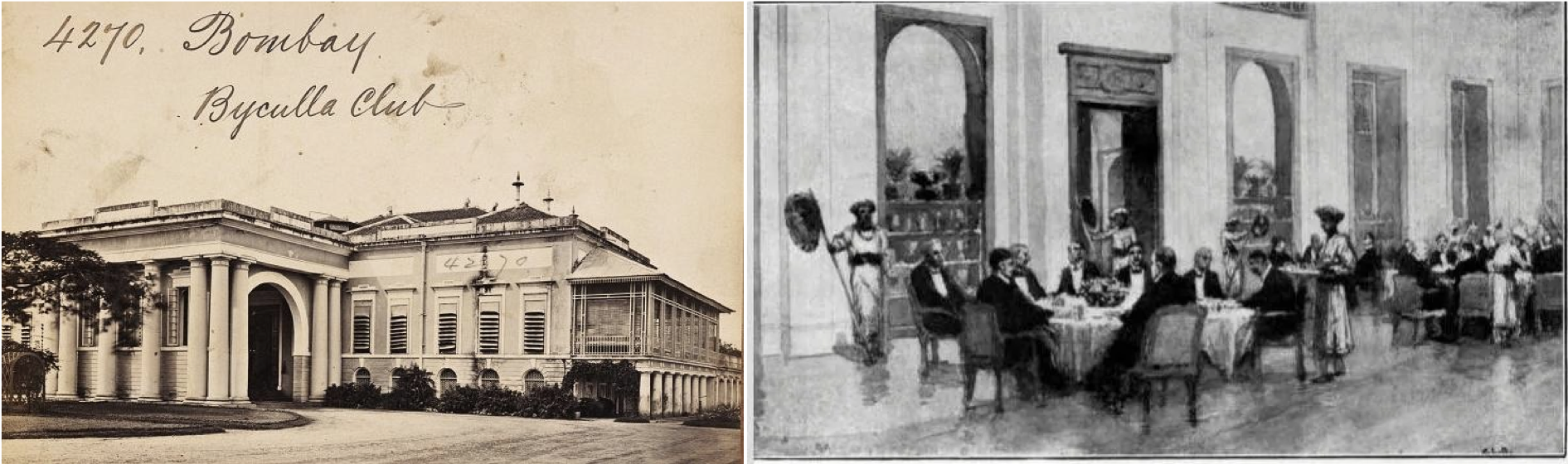

Private members clubs in Bombay represented the grandest stage for the parade of Yankee Tudor’s Ice. They were ultra-exclusive establishments, mostly off limits for Indians. These clubs - the most notorious of which was the Byculla Club, were set up to be oases for Anglo-Indians yearning for home. Their menus were replete with British favourites, and their evenings filled with elegant balls that were incomplete without chilled wine, crushed ice cocktails, soufflé, and well-preserved meat (standard ingredients for a sick party).

Unsurprisingly, members of the Byculla Club spearheaded the charge to raise funds (Rs. 10,000) for Bombay’s ice house as a service to society (and totally not so they could keep balling out). In an 1839 edition of The Bombay Times, they humbly claimed that "Society will be much indebted to the members of the Club, for their encouragement of this spirited undertaking, and we hope that measures may be arranged to give the public the full benefit of this important luxury."

It took several years for ice to filter down to the rest of Indian society (though it was always made available for medical use cases). This was partly due to the exclusivity of supply, and partly because of the price. Even the subsidised rates Frederic promised to Company officials were prohibitive to the average Indian. This was expounded in the years when freight charges were high in Boston because of unavailability of ships (eg: during the American Civil War), and later when duties and port charges were reintroduced.

But it is the arc of any pioneering technology to bend the scarce into the abundant. As ice imports eventually became a year-round practice, ice itself shifted from luxury to necessity to ubiquity. With every glass of chilled water sipped on an afternoon in May, ice in India shifted into the category of ‘one-way’ products that defy any economic handwringing about price and availability. Similar to modern inventions like smartphones, electric vehicles, air fryers, 10-minute groceries or Youtube Premium, the adoption is best measured not by the speed of growth, but the stickiness of the product (h/t Rory Sutherland, Chairman of Ogilvy). No one that tried Frederic’s ‘crystal blocks of Yankee coldness’ had any intention of switching back to their old way of life.

Even outside the palaces, hotels, clubs and government bungalows, people began to develop a taste for the cold. This was aided by the fact that ice had begun to (cheekily) find its way into the hands of the proletariat, illustrated by this entirely on-brand Subcontinental anecdote:

From a hundred tons imported in 1833, Indian ice imports went up to 3,000 tons by 1847. It wasn’t just the colonial crowd that benefited from ice. Similar to what it represented to the British Raj at the time, Calcutta became the jewel in Frederic Tudor’s empire. It catapulted his business to another level.

With the establishment of the Calcutta ‘plantation’, Frederic’s own total sales grew from 12,000 tons in 1836, to 65,000 in 1846, to 146,000 in 1856. This amount was shipped in 363 cargoes to 53 different places in the United States, the West Indies, the East Indies, China, the Philippines, and Australia.

He was also able to reap the fruits of his life’s experiments (even those had previously been his ruin). A not-immaterial portion of his India earnings came from the gradual inclusion of other products like Baldwin apples, grapes, butter and cheese that were preserved in barrels stored in the ice.

The ice trade also became a trojan horse for the movement of other commodities between America and India. Later ships ferried items like rock oil, drills, salmon, glass, lobsters, turpentine, painkillers, ink, and manufactured tobacco from Boston to the East Indies.

The profits from the Indian ice trade would emancipate him from his life-long shackles of indebtedness. From Calcutta alone, he would generate a profit of $220,000 over 20 years.

“Thus I have used fourteen years of my life, and accomplished the payment, at last, of principal of debt, as before stated, of $210,094.20 . and interest (to close of 1848) of $70,060.39 for a total of $280,154.59”

In January 1849, at the age of 65, he found financial freedom.

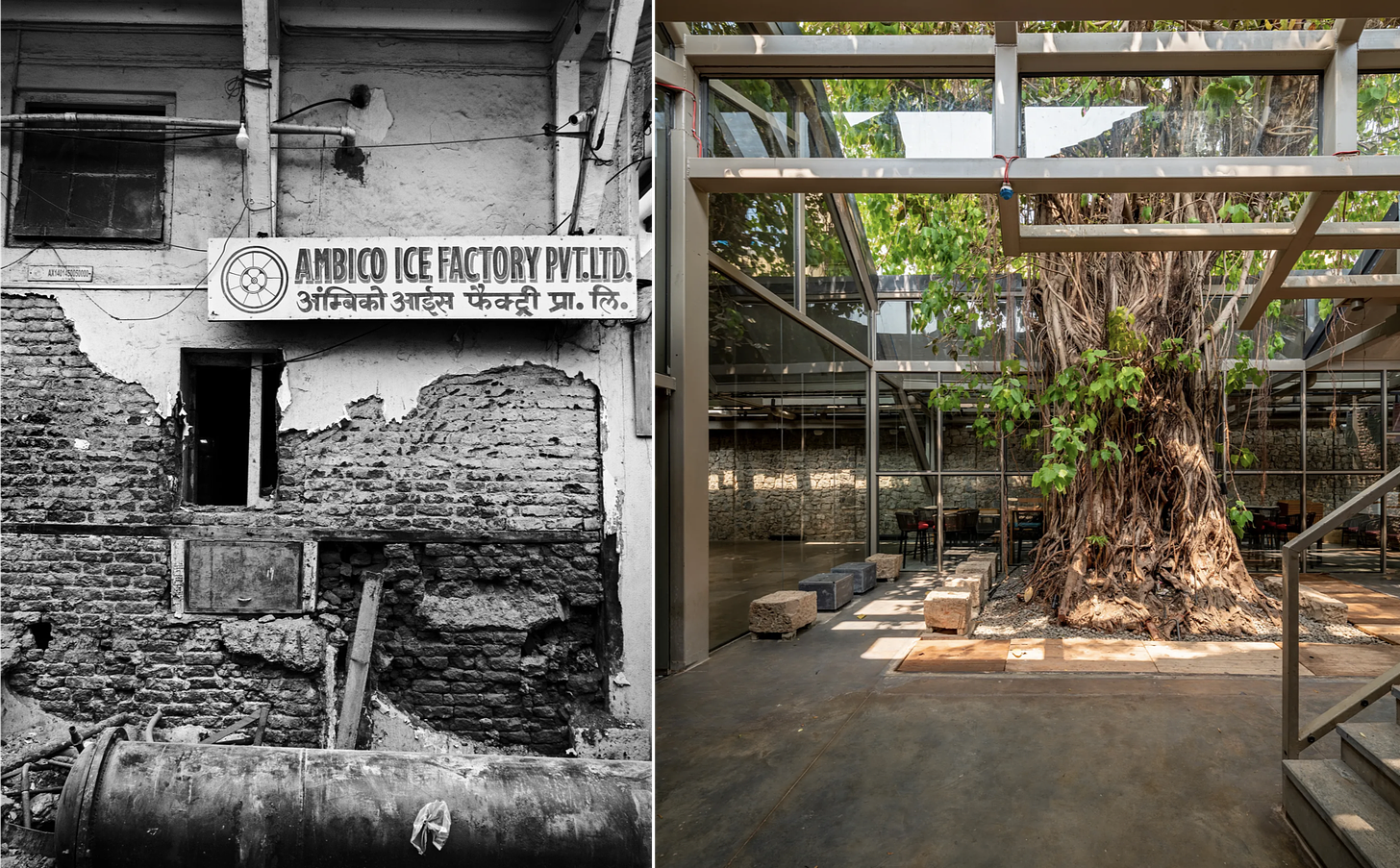

The natural ice trade continued to thrive till the last quarter of the 19th century, before it gradually petered out. The chief reason was that experiments with artificial ice production had started to mature. Various pioneers had figured out that by manipulating gas under a certain temperature and pressure you could mechanically create the conditions for cooling (basically how our refrigerators work today).

The benefits of man-made ice were assured cleanliness and regularity of supply. The colonial gentry would throw tantrums anytime there was an ‘ice famine’ in India due to factors like delays, warm winters, shipwrecks, unavailability of boats etc (this was a common occurrence during the Civil War in the 1860s). It meant there was an urgency to find a better, local, more reliable solution for their cooling needs. Once the Bengal Ice Company formed in 1878, the writing was on the wall. The supremacy of natural ice had ended.

The decline of the ice trade was exacerbated by the fact that New York and Philadelphia had replaced Boston as America’s leading ports. It meant that New England lost its economic advantage because ships no longer needed to fill their holds with ice for their outward journeys. This was coupled with the fact New England ice wasn’t what it used to be. The advent of steam engines and fossil-fuel based industrialisation had polluted the pristine waters of the American north-east. Given how important ice had become, no one wanted to take the risk of contaminating their drinks or food with dirty ice. Nature had become an unreliable supplier, which led to humanity taking ice making into its own hands.

Either way, a couple of decades prior to the conclusion of the once-thriving industry, Frederic Tudor had made the decision to move on. In 1860, he incorporated his sprawling venture into the Tudor Ice Company, and handed it off to younger successors. Accounting for the value of the ice business and the prime real estate he held all over New England, he was worth $200 million in today’s dollars. He had achieved his goal of amassing a ‘fortune larger than we shall know what to do with’. He would retire to his seaside estate to live out the rest of his days in peace.

Legacy

The ice trade was always hailed as a paragon of “Yankee ingenuity”, because it involved the creation of something out of nothing. By the time Frederic had ceded the throne at the end of his life (in 1864), he had infused a whole lot of something into nothing.

Ice was no longer seen as a ‘free good’ as it had been regarded in the early 19th century (because of its abundance and perceived uselessness). In New England you now needed to purchase sections of the shoreline of ponds and lakes in order to exploit the ‘right’ to harvest ice from those water bodies. ‘Ice rights’ became an economic asset that could be bought, leased, and sold. Fun fact - one of the ponds that became a reliable source of ice was Walden Pond, where, in a solitary cabin in the woods, one of the titans of American literature was busy writing his magnum opus just as the ice trade was picking up steam.

Observing the circus that unfolded every day on the surface of the ice-rich Walden Pond in front of him, Henry David Thoreau observed, with a mix of reservation and amusement, how:

“The sweltering inhabitants of Charleston and New Orleans, of Madras and Bombay and Calcutta, drink at my well…The pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganges.”

The ice trade had several second and third order effects (beyond ruining Thoreau’s nap time). For one, it made the electric refrigerator an essential household appliance in the 20th century. It also normalised the idea of artificially cooled (or conditioned) air. And strangely, it led to an exponential boom in the price of sawdust, originally a freely available waste-product that would ultimately command a higher price than the lumber from which it was discarded from. If you’d been paying attention at the time, there were probably hundreds of ways to capitalise on the ‘new normal’ presented by an increasingly refrigerated society.

The eventual global reach of Tudor’s enterprise makes it all the more egregious that the opportunity was entirely ignored by his contemporaries in the early days. Similar to how, say, Uber was underestimated as merely an app for booking black cabs (instead of a solution for all urban mobility), the ice business was grossly mispriced and underestimated by people who didn’t share Frederic’s vision.

The commodification of ice set the foundation for any activity or venture that depended on regular access to the cold. This includes everything from breweries (which use refrigeration to control the temperature during fermentation), to medicine (both the treatment of patients and storage of supplies like blood and vaccines), and ice cream (on its own a $100 billion industry in 2024). So much of our present form of civilisation has been built on a foundation of refrigeration. So much of the world is inhabitable because winter is a summonable condition. So much of our economy is rooted in ice.

Even today, dig just a tiny bit and you’ll see how so many companies (just in India alone) owe a debt of gratitude to the groundwork laid by Frederic Tudor and his original cold chain.

In our hyper-modernised societies today, we take for granted that only a few generations ago, regular access to ice was just a pipe-dream for a majority of Indians.

We often forget that the ability to tame the ambient temperature is still a luxury for most of India, and unfortunately one that still cuts across status lines.

There are plenty more yards to cover when it comes to fostering a more equitable distribution of thermodynamic autonomy (a real mouthful).

Even so, it’s worth appreciating that a million years ago it (probably) took the efforts of some enterprising hominid to endow humanity with the power to harness the heat. That it would take another million-ish years for most of humanity to be able to control the cold, speaks to the enterprise of a single ascendant Ice King.

There are few ventures in history that can boast a legacy akin to the ice trade. It makes it even harder to believe that, at a sweltering party in the summer of 1805, it all started with a joke.

On 13 February 1836, three years after his first ice shipment to India, Frederic wrote in his diary:

“This day I sailed from Boston thirty years ago in the Brig Favorite Capt Pearson for Martinique: with the first cargo of ice. Last year I shipped upwards of 30 cargoes of Ice and as much as 40 more were shipped by other persons… The business is established. It cannot be given up now and does not depend upon a single life. Mankind will have the blessing for ever whether I die soon or live long.”

This would turn out to be only the halfway point of his career, but even then, Frederic had already gifted the world a way to escape its climatic prison. Through his ruthless, tunnel-visioned pursuit of profit, he had planted the seeds of a thriving global trade - one which ultimately dealt in the currency of cold. In an economic arena that had once been dismissed by all his contemporaries, Frederic Tudor didn’t just see fertile soil. He saw ice.

Sources & Additional Reading

The Frozen Water Trade by Gavin Weightman

The Ice King: Frederic Tudor and His Circle by Carl Seaburg and Stanley Paterson

The Nineteenth-Century Indo-American Ice Trade: An Hyperborean Epic (1991) by David G. Dickason

Frederic Tudor Ice King - Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society (November, 1933)

November Meeting. Frederic Tudor, Ice King by Henry Greenleaf Pearson

Crystal Blocks of Yankee Coldness - The Essex Institute Historical Collections (1961)

Planning and Control in the 19th century ice trade - The Accounting Historians Journal (1984)

The Byculla Club, 1833-1916, a History by Samuel T. Sheppard

Bombay Place-Names and Street-Names by Samuel T. Sheppard

Shells From The Sands Of Bombay; Being My Recollections And Reminiscences, 1860-1875 by Dinshaw Edulji Wacha

PLAIN TALES FROM THE RAJ by Charles Allen

Bombay: The Cities Within by Rahul Mehrotra and Sharada Dwivedi

100 Years of Bombay: 1850-1950 - Art Deco Mumbai

Tides of Time by M. V. Kamath

Wanderings of a Pilgrim: In Search of the Picturesque by Fanny Parkes

The Imperial Diet of the British Raj: Food as cultural symbolism by Rituparna Ray Chowdhury

Bombay and Western India: A Series of Stray Papers (1893) by James Douglas

Letters from Bombay by D. Aubrey

The Global Merchants: The Enterprise and Extravagance of the Sassoon Dynasty by Joseph Sassoon

City of Gold: The Biography of Bombay by Gillian Tindall

American Ice in British India : the art of keeping cool! - The Heritage Lab