Hey folks👋

A happy (relatively) new year to all our Tigerbrethren (Tigerfeathren?), and a warm welcome to the 388 new subscribers who’ve joined since our last piece.

We’ve been doing this for four years now, which is the average length of time you’d have to wait for an Uber in Bangalore. Click here to skip the line👇

This edition of Tigerfeathers is presented in partnership with…Antler India

Antler is a global early stage investor with a presence in six continents and 27 locations around the world. Since launching in 2018, they’ve built a reputation for supporting entrepreneurs at the absolute first step of their founding journeys – with co-founder matching, business model validation, initial capital, and follow-on funding.

In 2023, Antler announced the imminent closure of their first ever investment vehicle dedicated to India - a $75 million venture fund to back early stage founders. Over three years of operation in the Subcontinent, more than 300 individuals and founding teams have partnered with Antler to build and launch their companies.

One of the key pillars of Antler’s India thesis is ONDC - the Open Network for Digital Commerce - which happens to be the topic of today’s essay. If you’re sufficiently excited by the merits of ONDC by the end of this piece and you think you have an idea worth building on, last year Antler launched a dedicated ONDC portal to support aspiring founders with capital, content, and a community to bring their visions to life. Consider taking a tour once you’re done here👇

Friends, it’s New Acronym season.

If you’ve somehow managed to dodge the hailstorm of headlines, special news reports, influencer reels, and ghostwritten LinkedIn posts about ONDC over the past 18 months - congratulations. It means you probably have a tantric level of control over your information diet.

However, in the likelihood that you haven’t, and in the off-hand chance that you’ve noticed a certain four-letter acronym creep into your peripheral vision, you might be aware that India is in the midst of another grand digital experiment.

For the uninitiated, ONDC - the Open Network for Digital Commerce - is an audacious attempt to reimagine how we buy and sell things online in India.

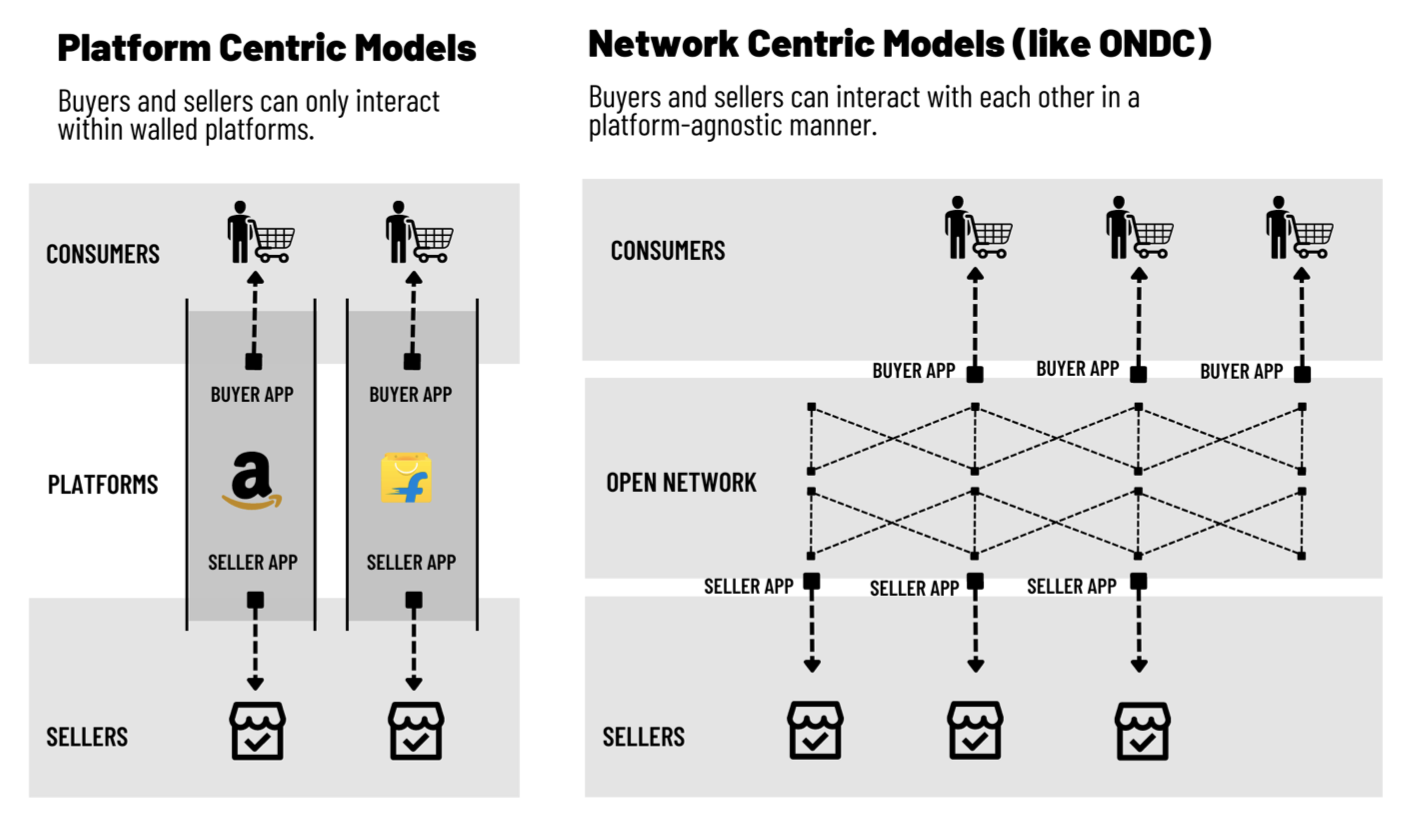

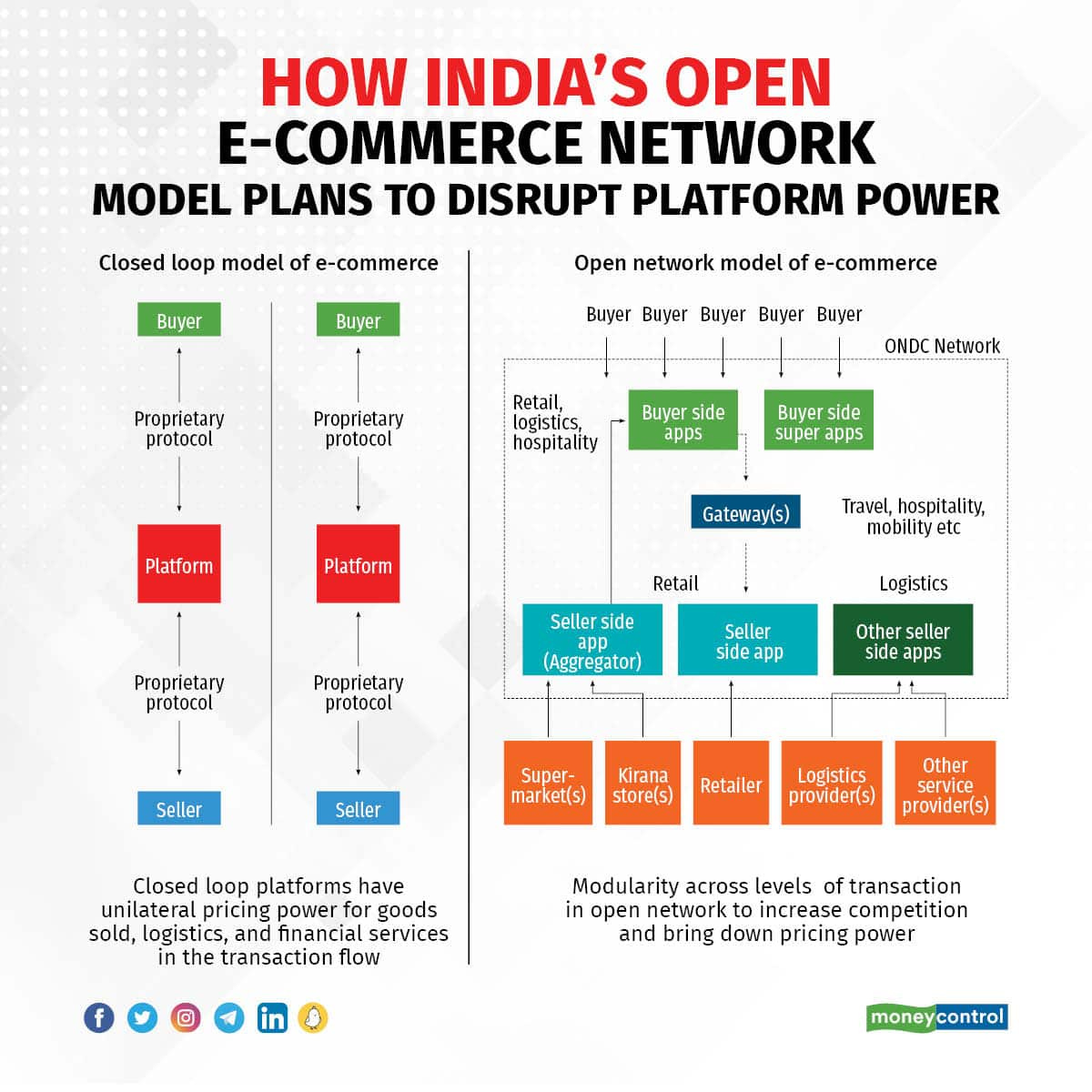

As the name suggests, it is an ‘open’ network, intended to be a philosophical counterweight to the idea of monolithic platforms (like Amazon, Swiggy, Uber, Bigbasket and others) that serve as gatekeepers to the bazaars of the Internet.

ONDC aims to subvert the status quo, shifting power to the edges instead of the centre. It sees e-commerce as a kingdom populated by millions of flourishing Davids instead of a handful of dominant Goliaths. It is a decentralised vision of digital commerce - inclusive vs exclusive - seeking to plug the holes in the vessel of India’s digital economy.

What holes?

It might not seem apparent to city-dwelling readers of this newsletter but, despite the immense strides we’ve made as a digital nation over the past decade, the penetration of e-commerce in India still sits at a paltry 5-6% of potential MSMEs, merchants, and sellers.

On the other side of the table, though it would appear that India has been quick to embrace the ease of online shopping, only 20-25% of Internet users in India have ever bought a product or service over the Internet.

It wouldn’t be controversial to suggest that the floodgates of India’s commercial Internet have yet to be fully opened. If you look at the raw stats, we’ve barely even scratched the surface.

ONDC is an attempt to correct that.

It is built around the idea that the poor participation of buyers and sellers in Indian e-commerce is mainly due to the tyranny of centralised platforms and aggregators (like those mentioned above). ONDC posits that the omnipotence, the rules, and the economics of this ‘platform’ model severely limit the number (and variety) of people and businesses that can participate in the digital economy.

It suggests that we need to lay out an entirely new and diverse set of welcome mats to usher in the next generation of online buyers and sellers in India. In other words, if we want to invite more participants to the e-commerce dancefloor, we need to start singing a different tune i.e. The Ballad of Unbundling and Interoperability.

Sounds like the worst song ever.

That’s fair.

But (questionable) jokes aside, the broad goal of ONDC is to re-architect the traditional boulevards of digital commerce to make more room for new merchants and vendors. To do that, it employs the twin tactics of unbundling and interoperability - two concepts that are embedded into the very fibre of the Internet itself (both literally and figuratively).

Instead of relying on the omnipotence and benevolence of centralised platforms to handle every aspect of online commerce (search, discovery, ordering, fulfilment), ONDC unbundles the different components of a commercial transaction into a series of interoperable lego blocks - almost like puzzle pieces that can then be snapped together in different combinations to create novel e-commerce products and services.

What that means in practice is that a single entity (like Amazon) doesn’t need to assemble all the bells and whistles to set up a full-fledged online marketplace. Different entities can handle the different components of e-commerce, specialising in specific services, products, sectors, geographies, or functions.

Some companies can focus on on-boarding sellers, others can focus on aggregating buyers, and a totally different set of players can focus on providing ‘enabling’ services like logistics, credit, cataloguing, inventory management, loyalty schemes, customer service etc. Because they are all part of the same network, ONDC allows each of these entities to be visible and discoverable to everyone else.

Each of these disparate components is orchestrated into a well-oiled machine by virtue of everyone playing by the same rules of this ‘Open’ network.

It’s the IKEA-fication of our digital economy.

It’s the choose-your-own-adventure version of e-commerce.

It’s the I’ll-probably-run-out-of-analogies-by-the-end-of-this-piece model of doing business on the Internet.

And it’s the first experiment of its kind anywhere in the world.

Cool but why should I care?

Because the bull case for ONDC is that it exponentially increases the depth and breadth of India’s digital economy in the years to come. The hope is that over the next 5-10 years, ONDC will:

give Indian buyers a far greater choice over what, where, and how they purchase things online

bestow Indian companies, brands, and sellers with more control and agency over their e-commerce operations; reduce their dependence on a small coterie of dominant marketplaces; and open up an entirely new channel of distribution for their products and services

give Indian founders and teams (both old and new) a wider canvas to participate and experiment across the e-commerce value chain

As far as grand experiments go, ONDC is consistent with India’s recent approach of building public ‘digital’ infrastructure to power our modern digital economy. Much like how Aadhaar, UPI, and Account Aggregators serve as the bedrock of digital identity, digital payments, and digital data, in a fully realised state ONDC could serve as the foundation for digital commerce in India, inconspicuously orchestrating the exchange of goods and services around the country.

If all goes to plan, it has the potential to add another engine to our economic machine and lift the curtain on the next great epoch of India’s digital story.

No biggie.

So, whether you’re a seller of goldfish, protein bars, magician services, unleaded diesel, padel tennis courts, gold loans or recycled aluminium dross; whether you plan to sell something hyper-locally, nationally, or even internationally; the potential scale of ONDC’s impact makes it a topic worth understanding.

Okay, but why write about it today?

Because ONDC has just graduated from the primordial ooze stage of its development. 18 months in, it would appear that this thing has wings, but it isn’t clear whether it’s going to evolve into a dragon or a dragonfly.

That’s what makes it the perfect time to do a piece on ONDC. It’s hard to know for certain how this plays out, kind of like looking at UPI in 2016 or Bitcoin in 2011 or smartphones in 2008. But we’re at a point where you can look at the tech, look at the market, and look at the data, and try to make an educated guess about what the future looks like. That’s what I’ve hoped to do here.

Alright I’m in.

Nice.

Now that we’ve gotten the pleasantries out of the way, today’s essay is divided into three parts that aim to:

Part 1

contextualise the idea of digital public infrastructure (DPI) in India

illustrate how ONDC fits into this journey

provide an overview and background on ONDC

Part 2

explain how ONDC works and the roles of various network participants

dive into the Beckn protocol, which is the technical scaffolding that underpins ONDC (and could end up being one of India’s most significant contributions to the global Internet)

Part 3

lay out the current status quo in the ONDC ecosystem, and spell out what you can and can’t do today

outline various mental models for building, investing, and betting on ONDC

Depending on your prior knowledge of the topic, you can probably teleport to your preferred starting point. It is, however, designed to be read as a linear story.

That’s a fair bit to cover. We should probably get going, no?

One last disclaimer before we kick things off - as you can probably tell by the scope of the index, this is not a light read.

It is the outcome of four months of research and close to a hundred conversations with participants from every corner of the ONDC ecosystem. It is data-dense, insight-rich, and meme-friendly. But it’s not a light read. This is not the kind of thing you’d breeze through while getting a tan on a beach in Phuket (unless you’re a sicko). My goal was to attempt a comprehensive summary of the ONDC story so far, and present a balanced view of what the future looks like.

If I had to say, the audience I envision getting the most out of this piece is people who have a serious interest in ONDC, and people who have a serious interest in having a serious interest in ONDC.

Here’s the kicker: if this moonshot project manages to fulfil its lofty mission over the next 5-10 years, then - much like UPI - everyone in India will have to take a serious interest in ONDC at some point.

But enough chit chat. With that, our story begins.

If you’ve visited Mumbai at any point in the last six years, chances are you’ll have encountered a city in flux.

India’s commercial capital is currently a work in progress. Over much of last half-decade, the city has been dissected all along its North-South corridor, exposing the entrails of two major infrastructure projects that are both scheduled to go live sometime this year.

These projects - the Mumbai Metro line and the Mumbai Coastal Road - are colossal, pivotal endeavours. They were undertaken with the hopes of finally relieving the city of its chronic traffic chokehold - like a double Heimlich manoeuvre caste in concrete.

Although the current phase of construction has been underway for *only* around seven years, ask any Mumbaikar and they’ll tell you the city’s been under renovation forever. That’s what it feels like anyway. Mumbai is cramped in the best of times, so it’s hard not to be viscerally aware of when it’s in the midst of large-scale change.

The disruption is palpable.

Your face is caked with dust the moment you leave home. You have to budget for an extra 10 minutes for your commute to work. Your lunchtime dosa stall has moved 500 metres down the sidewalk to make way for a new metro station. Your night time serenity is frequently pierced by the sound of large trucks, larger drills, and falling boulders.

There is a tangible interruption to your life and routine.

But, as always, the city adapts. As residents, we buy into the implicit agreement that our present inconvenience is a fair price to pay in exchange for a city that is hopefully much kinder to the movement of people and things.

In all likelihood, by the end of the year, we won’t even remember being in this phase of metamorphosis. As with every infrastructure project in Mumbai’s history - the highways, bridges, flyovers, reclamations, ports, causeways and expressways - the memory of the disruption will fade. We’ll adapt once again, enjoying the fruits of an upgraded urban anatomy with vastly improved circulation.

Okay Bob The Builder. What does this have to do with anything?

We’re getting there.

The legacy of these iconic civic projects is not the cosmetic changes to Mumbai’s skyline, nor the frustration over the years of construction that precede their addition to the city’s silhouette. Instead, the fruits of metamorphosis are evinced in the behavioural shifts and economic opportunities that are unearthed as a by-product of adding new pieces to our metropolitan puzzle.

You see it in the soaring real estate prices of newly accessible neighbourhoods. You take comfort in the improving speed and efficiency of local emergency response systems. You revel in the pride of a city that is better placed to play host to global conferences and spectacles like the G20, World Cup and the Olympics. You feel the ramping up of mercantile energy - of people showing up from far-flung neighbourhoods, cities and countries to trade products, cultures, and ideas.

For Mumbaikars that are eagerly awaiting the chaos of construction to subside, there is plenty to look forward to at the end of the year.

For starters, the traffic and air quality will hopefully improve as more people switch over from private cars to public transport. (There’s also a chance it even gets worse as more people get comfortable with the idea of commuting into the city for work, but it’s hard to say in advance).

On a personal level, residents can look forward to having their favourite restaurant be able to deliver to whichever corner of the city they’re holed up in. Or having their evenings open up for the gym because their commute times just got divided in half. Entrepreneurs will likely have a broader catchment area for new hires because people can travel in from further away. Roadside romeos can look forward to a wider pool of Tinder matches for the same reason.

Some of these changes will play out overnight. Others will take months and years to make themselves apparent. Some of these are predictable developments. Others are emergent phenomena (both good and bad) that require creative second and third-order thinking to foresee.

The salient fact is that, for one, cities level up when you make it easier for people and things to move around. Each new layer of concrete adds a new base from which action and innovation can flourish.

Two, when the public and private sector collaborate to build crucial pieces of urban infrastructure, usually that sets the table for commerce to blossom. Better public infrastructure is a catalyst for enthusiastic private enterprise.

And finally, and perhaps most importantly, when it comes to taking advantage of new opportunities yielded by new technology, there is considerable merit in being able to see around the corner.

Okay, so what?

Unless you’re in the business of building digital products, unless you spend a decent chunk of your time in Bangalore or Bangalore-adjacent circles, unless you’ve been reading Tigerfeathers over the past four years, you might be unaware that, since 2008, India has taken the principles of building physical infrastructure and transposed it for the digital realm.

In other words, in the last decade and a half, much of India’s digital economy has been been constructed over a scaffolding of digital public infrastructure (or DPI) - made up of lightweight software platforms that mimic the effects of building roads, bridges, ports and highways in the ‘real world’ - i.e. they help to lubricate the movement of people and things online.

The spine of this programme - sculpted around Aadhaar, UPI, and Account Aggregators - was devised to provide Indian citizens with a portable biometric digital identity, a mechanism for making cheap real-time mobile-first digital payments, and a framework for managing and leveraging their digital data, respectively.

Each of these seminal projects was conceptualised on the assumption that the Internet would be a permanent, pervasive part of our lives; that it would capture a larger and larger share of our socioeconomic activity and attention; and, in India’s case, the vast majority of our population would interface with the Internet only via a mobile phone.

“It is less about scaling what works, and more about figuring out what works at scale.”

- Sujith Nair (CEO & Co-founder at FIDE | Genesis Co-author & Steward - Beckn Protocol)

“Fundamentally, India is going from an offline, informal, low productivity, multiple set of micro-economies to a single online, formal, high-productivity mega economy, a trend that will continue over next 20 years.”

- Nandan Nilekani (Founding Chairman, UIDAI)

That’s what makes India’s DPI strategy a groundbreaking ‘first-principles’ approach to nation-building in the digital age. Not only did it help us overcome the paucity of our national physical infrastructure in the 2000s, but together this digital stack (re: India Stack) has progressively aided the flow of people, money, and information in India’s digital economy over the last decade.

Several of these tools - like e-KYC, UPI, FASTAG and DigiLocker - are ubiquitous utilities today. They are familiar names to most Indians, used on a daily basis to do things like identity verification at airports, opening a bank account, settling a bill at dinner, making automatic electronic toll payments on highways etc.

Others, like the Aadhaar Payments Bridge System (APBS), came to India’s aid during the pandemic, allowing the government to disburse emergency funds directly into the bank accounts of nearly 500 million people in need; The Digital Infrastructure for Knowledge Sharing (DIKSHA) platform is being used to deliver educational content to almost 200 million Indian students and teachers; The Bharat Bill Payment System (BBPS) has created a standardised facility for bill payments across 24+ categories including utilities, school fees, and loan repayments.

We don’t think of these tools as ‘infrastructure’, the same way we don’t think of GPS as infrastructure when we’re using Google Maps, or the way we don’t think of the Internet as infrastructure when we’re posting a 🔥🔥🔥 selfie on Snapchat.

That’s largely down to two reasons.

???

Oh now you’re interested?

Spit it out man.

For one, the term Digital Public Infrastructure (or DPI) has only really become embedded in the global tech lexicon over the past 18 months. The general awareness and interest in India’s DPI efforts particularly ramped up over the duration of India’s presidency of the G20 (from December ‘22 to November ‘23). This has been amplified by the mounting evidence that India’s investment in DPI has significantly turbocharged its development trajectory in the 21st century.

These days you don’t have to search too long to find mention of DPI in news headlines, academic papers, and statements from policymakers and world leaders, something that wasn’t the case even just a couple of years ago.

And secondly, people don’t really engage with these tools directly. More often than not we benefit from DPI ingenuity via the interfaces of private companies and startups.

We make payments using UPI via our PhonePe and Google Pay apps. We use our Aadhaar number as part of the KYC flow while signing up for a Zerodha DEMAT account or an ICICI bank account. We load up our FASTAG wallets via our PayTM app. The ‘infrastructure’ typically hums in the background as we go about our digital routines.

That’s the real magic of India’s DPI programme. It’s not about the infrastructure itself, it’s about what you can do with it. You won’t spend much time fantasising about the glistening asphalt of some newly inaugurated interstate highway. You’re just happy you can drive to Goa in half the time.

Outside of interest rates and credit cycles, it’s been the installing of new digital tracks in the 2010s that has helped catalyse successive seasons of startup fertility in India, directly or indirectly leading to our ascension as the third largest startup market in the world.

Like what?

EXHIBIT A: The largest telecom provider (Reliance Jio) and second largest online broker (Zerodha) in India being able to onboard hundreds of millions of new users cheaply, quickly, and digitally via Aadhaar based e-KYC.

EXHIBIT B: The digitisation of off-line retail in India via interoperable UPI-based QR codes planted by fintech startups.

EXHIBIT C: The explosion of mobile gaming as a leading form of entertainment in India boosted by the ability of consumers to make low-cost, small-ticket, and even recurring payments on UPI.

It wouldn’t take much effort to organise Exhibits D-Z either. Examine the machinery behind some of our biggest digital lending, streaming, entertainment and consumer goods companies, and you’ll find many of the same DPI nuts and bolts.

Public infrastructure sets the table for private activity and innovation. That’s the thesis behind our DPI efforts. These utilities represent a chest of toys for entrepreneurs and operators to play with. That’s why it’s worth paying attention when a new lego set is added to the collection, because it typically heralds the onset of a new startup season in India.

And that’s where ONDC comes in?

Almost there.

C’mon man.

Sorry.

But before we get there, it’s important to briefly unspool the philosophy that underpins this approach, because it extends to ONDC as well.

The core idea behind India’s DPI strategy - one that we highlighted in our piece on India Stack from 2021 - is that every individual in the Internet Age should be entitled to certain ‘fundamental digital rights’ so that the bounties of cyberspace aren’t reserved for just the most privileged sections of society.

For instance, every citizen should have the power to digitally authenticate their identity, every citizen should have the ability to send money to someone else, every citizen should be empowered to decide who can access their data, every citizen should have the right to access a national marketplace of buyers and sellers…and so on.

Now, most countries around the world are on board with this thesis, though there are considerable differences in how they choose to implement this doctrine.

The US has taken a characteristically laissez-faire approach, letting private sector heavyweights like Facebook and Google manage the digital identities of their citizens, or companies like Block (CashApp) and PayPal (Venmo) operate independent closed-loop systems for mobile payments.

Europe has chosen to lead with a typically regulation-first strategy, implementing landmark pieces of legislation like the GDPR and PSD2 to ensure that citizens of the EU can safeguard their personal data. The UK has its Open Banking initiative that has laboured to give citizens control over their financial data.

There’s even an entire legion of crypto-libertarians that believes that these ‘sovereign’ digital rights over identity, payments and data should be conferred by public blockchain platforms and private keys, and not any divinely ordained nation state or corporation.

And India’s approach is different?

Yeah. It’s the first of its kind. And it’s the result of a collaborative effort between policymakers, technocrats, think tanks, volunteers, private sector luminaries and market participants to figure out how best to employ ‘population-scale’ technologies to tackle India’s biggest social and economic problems.

It’s the techno-legal version of go-big-or-go-home.

“Digital Public Infrastructure has fundamentally changed the way samaaj, sarkaar and bajaar are interacting with each other.”

- Nandan Nilekani (Founding Chairman, UIDAI)

The Indian DPI blueprint acknowledges that certain digital activities are too important to be left to unfettered capitalism. But it also recognises that the state should not be in the business of making and operating sophisticated digital products.

So we’ve found a middle ground.

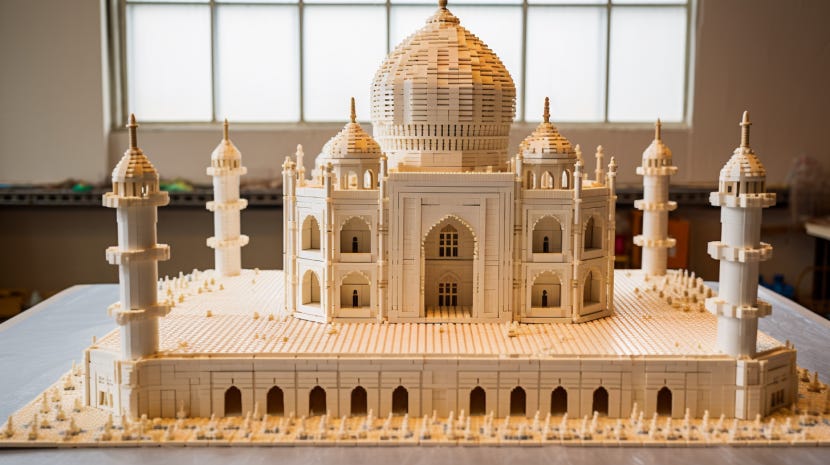

“There is a game called Jenga - you know where people stack blocks, and then what happens is the game begins. Everybody starts pulling one block at a time until everything collapses. India is not playing Jenga. India is playing another game called Lego. We are building blocks. We are building digital blocks, and these digital blocks, when you re-arrange them, reconfigure them, they are going to tell their own India's digital story”.

- Sumit Seth, Joint Secretary (Policy Planning & Research), Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India

Under this strategy, the government’s role is to create lightweight digital building blocks that can be freely used as the foundation for private sector ingenuity.

As Sujith Nair (Co-author and Steward of the Beckn Protocol) says, DPI is “the most minimal footprint of a technology that emits power that does not extract power”. Over the years, the hallmarks of this DPI approach have included:

The stewardship of individual programmes and networks by non-profit entities working closely with the government bodies and regulators (eg: UIDAI for Aadhaar, NPCI for payments, Sahamati for Account Aggregators)

A minimalist prescription of technical standards and specifications so private companies can get creative on the design and form factor of their solutions (eg: voice based authentication of UPI transactions)

The enshrining of interoperability as the dominant allele within the DNA of this DPI model

The last point is perhaps the most crucial component. Interoperability is what allows someone to make a UPI payment from their HDFC account using PhonePe to someone else’s ICICI account using Google Pay. It’s what enables an Account Aggregator app to integrate with all the financial institutions on the network with just a couple of APIs, instead of going through the effort of setting up hundreds of bilateral integrations.

This sets the stage for combinatorial innovation, meaning that different individual components of DPI can be stacked together to create more complex products and services (like the Open Credit Enablement Network or the National Health Stack). The impact of new DPI initiatives, then, isn’t just additive, it is multiplicative. Exponential, not linear.

A by-product of DPI interoperability is that entrepreneurs are compelled to ensure the highest standards of user experience and service delivery because unhappy consumers can easily switch to a different product within the same shared digital ecosystem. Eg: if your PhonePe transactions are frequently failing, you can switch to Google Pay and it would make no real difference to your life.

This feature obviates the need for paternalistic regulatory frameworks and pernicious anti-trust interventions. Because fundamentally, it’s hard to attain a monopolistic position or extract rent as a middleman when your underlying tech stack is based on a set of commoditised building blocks. You need to try extra hard to give people a reason to stick around in your playground without any walled gardens to keep them locked in.

That’s kind of a tricky environment if you’re trying to build a moat for your digital castle, no?

It is. It’s what makes India a unique arena for digital capitalism, different from anywhere else in the world.

For private players, the proliferation of DPI has invited its own set of opportunities and challenges to the digital value chain, though these aren’t where you’d usually expect to find them. The interoperability inherent in this approach means that conventional profit pools are often scattered to unconventional (and even unexplored) parts of the digital economy. They might shrink in some areas and blossom somewhere else.

That’s the trade off. When you make it exceedingly easy for entrepreneurs to burst out of the starting gate, you also step on the toes of everyone who’s made a head start.

Looking back, the proliferation and adoption of UPI effectively killed the ecosystem for digital wallets in India, but it also gave leading wallet providers like PayTM a new hook to acquire customers, who they could then cross-sell lucrative financial services like loans and insurance. Banks lost out on interchange fees because the government chose to make UPI transactions free, but it also meant that a far greater number of people came into the formal financial system, swelling the deposits of Indian banks.

…This kind of efficient, inclusive infrastructure might eat away at some private sector profit pools in the short run, but those profit pools will reappear and grow larger as the engine of progress chugs along.

…At the end of the day, all of this comes back to economic primitives. Whenever a new solution makes it easier, cheaper, or more convenient to do certain repetitive, abstractable tasks, not only does the new mechanism replace the incumbent, but all of society benefits as a result. Productivity increases. New ideas emerge. Lives improve”.

Ultimately it’s not about finding creative ways to carve up the same slice of the pie, it’s about increasing the size of the pie for everyone - consumers and businesses alike. The choice of approach is not a philosophical argument over public vs private or open vs closed or top-down vs bottom-up. It’s about which approach the market ultimately deems is best.

So what’s the catch?

Well, there is a chorus of people who would argue that the government shouldn’t be in the business of building any tech at all, that this DPI strategy unfairly negates the time and investment spent by private companies to capture a particular market.

However, even those people would find it hard to argue that this approach hasn’t been effective at speeding up inclusion. The numbers speak for themselves - 1.3 billion Indians have a digital identity today, there are 700 million+ Aadhaar-linked bank accounts, UPI does more than 10 billion transactions per month, and so on.

Would a private company (or private companies) have gotten there faster? Would the private sector, left alone, have gotten there at all? What’s the incentive for profit-seeking corporations to cater to the billion+ Indians at the bottom of the pyramid that won’t move the economic needle in the short term? Should the Indian state apparatus be more concerned about preserving the supernormal profits of a handful of giant tech incumbents, or about bringing the maximum number of individuals under the canopy of India’s digital economy as fast as possible?

Since the arrival of the smartphone age on the Subcontinent, the evidence would suggest the latter. The focus, then, has been centred on how to make it cheaper, better, faster and more convenient to do the tasks that make up an essential digital routine.

That same tide is now crashing towards the shores of Indian e-commerce.

Now we get to ONDC?

Now we get to ONDC.

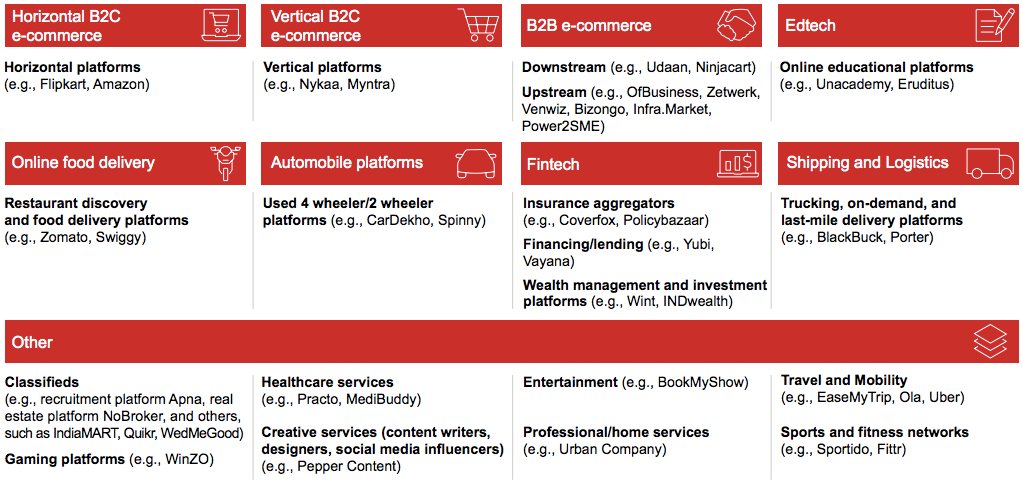

For the last 18 months, the Open Network for Digital Commerce has grabbed national (and international) headlines as the glitzy new addition to India’s DPI roster.

For our Indian residents, you might not have felt the dust in the air or heard the sound of loud drills at night, but make no mistake, this is a massive infrastructure project with moonshot ambitions.

ONDC is attempting to apply the principles of DPI to the realm of digital commerce. Similar to our other India Stack efforts, the idea is to strip down the value chain of e-commerce to its bare bones, creating a set of lightweight interoperable building blocks that allow any entity to ‘turn on’ e-commerce capabilities and, in the process, come aboard a shared commercial network. It’s like a come-one-come-all digital mall in cyberspace.

And to create this mall, ONDC effectively unbundles the customer side of the marketplace experience from the seller side.

Instead of a single marketplace platform where buyers and sellers meet, on ONDC, there are buyer side platforms (called ‘buyer apps’) that aggregate consumers, and seller side platforms (called ‘seller apps’) that aggregate merchants. By virtue of being on the same network, every buyer is visible to every seller (regardless of which buyer app or seller app they use) and vice versa.

This means that, as a consumer, you can enter this ‘digital mall’ from any of the entrances provided by buyer apps on the network (and you will be able to ‘see’ all the sellers/brands that have an ONDC storefront. And as a seller, you can use any seller apps to set up shop in this mall, and you will be ‘accessible’ to every buyer.

In the ONDC world, nobody is limited to the confines of any single platform.

This type of unbundled, open architecture also increases the surface area for third parties to offer specialised services across the e-commerce value chain (like logistics, cataloguing, AI chatbots, inventory management, insurance, customer intelligence etc). Over time the expectation is that this approach will open up the benefits of e-commerce to geographies, sectors, products and people that have been left out of India’s Internet story so far.

The stated goals for ONDC over its first five years are to:

📍Add $48 billion worth of Gross Merchandise Value (GMV) to India’s e-commerce market

📍Increase the penetration of e-commerce from 5-7% to 25%

📍Bring in 900 million buyers and 1.2 million sellers into the e-commerce fold

Okay okay can we slow down a little? How does this all even work? Why do we even need any of this??

I’m glad you asked. Welcome to…

In this segment, we’ll understand how ONDC actually works. We will also look at why it could be a big deal not just for India, but for the Internet as a whole. With that being said, let’s establish a few things before we jump in.

This will be a non-technical explainer: After many rewrites and a bitter struggle to contain the inner urge to explain every technology down to the minutest detail, I’ve decided to keep this one (relatively) simple. If you are looking for a scientific exegesis of the system, this is not the place. Instead, I’ll make heavy use of analogies to get the main points across.

We may omit or amend certain details for the purpose of simplicity: While this explanation will certainly get all the core ideas across accurately, the priority is conceptual clarity not microscopic accuracy.

Alright, with that out of the way, let’s jump right in. There is a big problem in the world of digital commerce today.

Go on, do enlighten us.

The major problem with digital commerce today is that it is dominated by a handful of large marketplace platforms.

Think Amazon and Flipkart for e-commerce, Swiggy and Zomato for food delivery, or Uber and Ola for ride hailing. Everyday consumers may not even be aware that there is any problem here, but allow us to present some of the issues.

Issues For Sellers:

The platform takes a chunky commission on every sale. For e-commerce that figure is ~15%, for food delivery it is 20-35%, and for ride hailing it is ~20-25%.

You are at the platform’s mercy when it comes to how your product is ranked in search results shown to users. Most sellers therefore have to buy ads on the platform to get more eyeballs and visibility with buyers.

Sellers don’t get much data about the customers who buy their products, nor are they able to communicate directly with their customers.

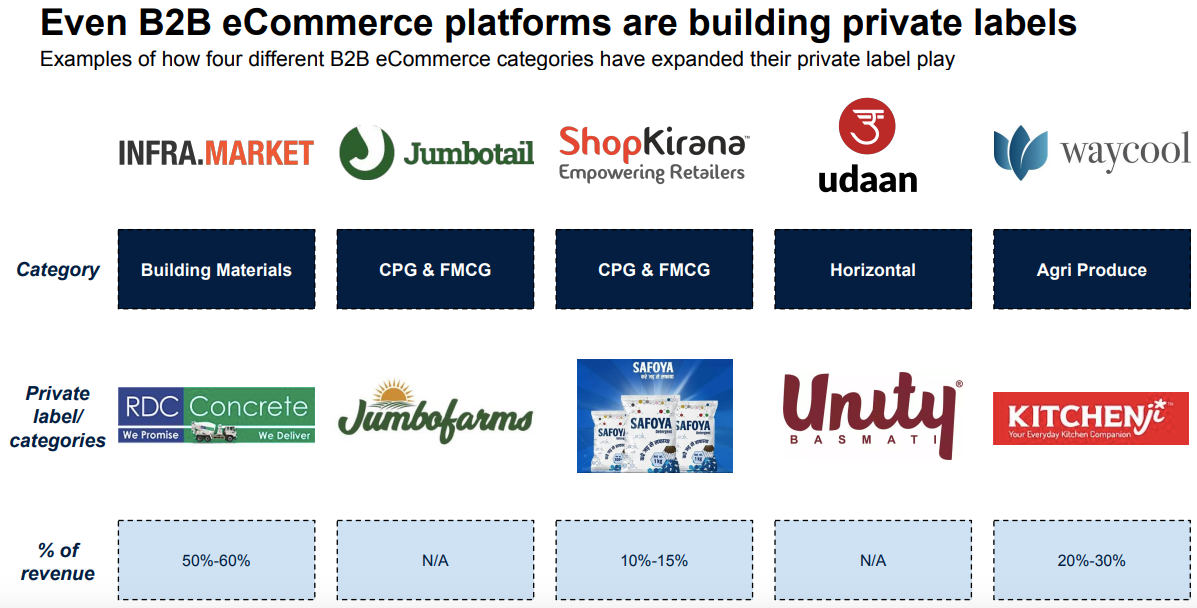

To make matters worse, the platforms often take learnings from successful sellers and copy their products. They then market those white-labeled copies to the seller’s customer profiles.

The seller’s history and reputation is completely tied to a single platform. Imagine you have been selling beanbags on Amazon for years and have amassed hundreds of reviews and 5-star ratings from satisfied customers. All that history will be lost the day that you leave Amazon or have your account suspended for whatever reason.

Issues for Buyers:

Buyers are not easily shown multiple offers and quotes for a single product. If you were to ask a dozen small retailers their best price for a box of Nutella, you would get a range of different prices, payment terms, and delivery times. But with Amazon, you have to really dig through the app to see alternate offers.

Buyers may be pushed towards buying products that drive maximum profit for the platform instead of the best or most suitable product for the customer. To extend our Nutella example, Amazon will push you a jar of Nutella priced at Rs. 339 even though one of their third-party sellers is offering a price of Rs. 320. In categories where the platform possesses its own brand, they will push their own line of products (eg. Amazon Basics) even if one of their sellers has a superior product.

Now, all this isn’t to say that platforms don’t work or have no value. On the contrary, they do many things exceedingly well and they create a ton of value for both buyers and sellers.

But how much more value would be unlocked if we could find a way to resolve these issues? How much are we leaving on the table by accepting the status quo? Given that most of us only know e-commerce as platform commerce, what kind of possibilities could we unlock just by questioning whether there was a different way to do this?

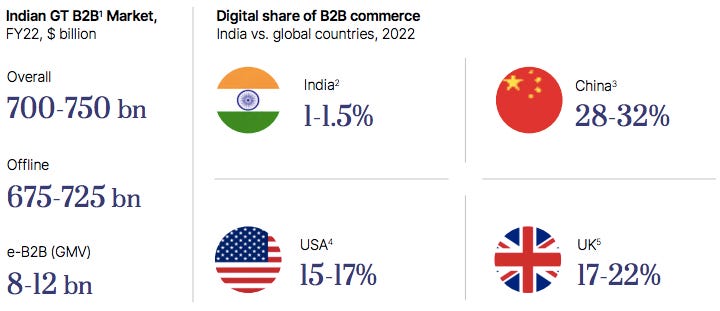

Market data suggests that e-commerce constitutes only some 5% of retail spending in India, in contrast with 25% in the US and 35% in China. There are countless small businesses in this country that have hitherto still not managed to tap into and benefit from India’s digital growth story that we hear so much about.

These businesses are tiny, vulnerable, and generally unsuited to surviving in a world of high commissions and low flexibility. They need a different kind of solution. And that is what ONDC is attempting to provide.

Why has no one else tried to build a better model?

That’s a great question. Many people have tried to build alternatives to large platforms in the past, but it is very, very difficult, because platforms are very, very good at what they do.

Let’s break down all the things a marketplace platform really does. In essence, a marketplace platform brings together buyers and sellers and helps them carry out transactions. To succeed in this line of business, the main two things needed are lots of buyers and lots of sellers. This is much easier said than done.

Just consider the following problem: buyers want to use a platform that already has lots of items for sale; sellers, on the other hand, don’t want to waste time selling on platforms where there is no demand for goods. See the catch here? This is known as the cold-start problem or the chicken-and-egg problem. It has bankrupted many, many, companies.

That is not to say that it is impossible to build a successful marketplace platform! Flipkart itself was born as an upstart challenger at a time when Amazon completely dominated the (admittedly nascent) Indian e-commerce market. Furthermore, other companies like Nykaa, Zetwerk, and Infra.market have successfully built vertical marketplaces that focus on specific categories of products (fashion/beauty, manufacturing, and construction, respectively).

But despite these few successes, the startup graveyard is chock full of the skeletons of companies that tried to build marketplaces but could not succeed because it is simply too expensive or difficult to overcome the cold-start problem. And as for the survivors? Well they end up looking more and more like the platforms they set out to disrupt in the first place. They end up pushing their own products or charging huge listing and commission fees. In short, they end up perpetuating the platform problem with more platforms.

So what is the solution, and where does ONDC fit in?

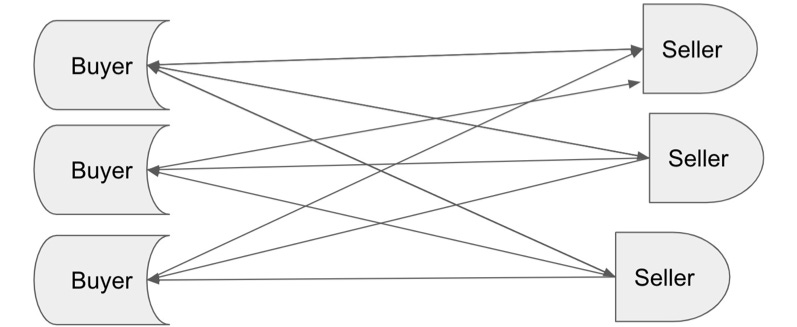

Before coming to ONDC, let’s just try and imagine the different ways to structure a marketplace. We’ve already seen the platform model, wherein all buyers and sellers congregate in one place.

As shown above, all the buyers and sellers in this model connect with the central platform which handles every piece of the transaction.

But what about an alternate model? Can buyers and sellers connect directly and cut out the intermediary?

The answer is yes. But the catch is that the complexity and coordination overheads rise exponentially.

In the first model, we saw that buyers and sellers are only required to maintain one connection - denoting technical, commercial, and operational integration - with the platform.

However, in the second model, we can see that each buyer and seller has to maintain three connections - one for every counterparty they wish to coordinate with. And it doesn’t stop there - the number of connections keeps rising as the number of counterparties increases. This is not scalable, especially when you consider that each of these connections may require some element customisation and special attention.

Are you saying that direct sales between buyers and sellers don’t work?

No, not at all. They can work very well, and they have several benefits:

The sellers have direct control over all communication with the buyers

The sellers don’t pay hefty fees to platforms to list, advertise, or sell their products

The sellers maintain their own records of reviews, complaints, and testimonials

Since the sellers don’t have to pay commissions to the platforms, they earn more for the products they sell. They can in turn pass these savings on to the buyer.

These are significant benefits, and they explain why we see a lot of sellers go to great lengths to directly reach their buyers. They often do this through their own apps or websites (or by using e-commerce enablers like Shopify or WooCommerce). We call this the Direct-To-Consumer (D2C) model, and there are many examples of successful D2C brands, you can even read our piece on the dawning of the Indian D2C era here:

Think of homegrown brands like MamaEarth, Boat, or MyMuse. These companies use clever marketing and media strategies to inform and entice viewers to come and buy their products directly from their respective websites. But despite that, they still sell across a variety of platforms such as Swiggy, Zepto, Flipkart, and Amazon (as well as various offline retail outlets). That is a lot of different sales channels to manage - ask any of these companies and they will tell you that they need entire teams to manage each of these connections.

So just imagine then the fate of small sellers who wish to sell directly to their customers. The D2C companies we have just mentioned are all new-age, venture-funded, technology-savvy businesses. They are very different from the average kirana shops or small regional brands that account for >80% of the retail sector in India. How can these MSMEs manage direct digital sales?

I dunno man, why don’t you tell me?

Well, there are solutions for this category too. “Kirana-tech” companies like Dukaan and Bikayi raised lots of money to help small retailers build and operate digital storefronts through which buyers could browse a catalogue, select items, and directly place orders. This trend seemed neat at the time, but it has failed to deliver on its promise for one major reason: it doesn’t help the sellers bring in more demand. And more demand and more sales is all that really matters at the end of the day.

That is the same reason why all the D2C brands we mentioned above continue to sell on the likes of Amazon despite operating their own direct online stores. Amazon has a lot of users, which means lots of potential sales for these D2C brands. This is so valuable for brands that they actually sell their own products for heavy discounts on these platforms just so they can be discovered by more buyers. Just look at the price of 1 litre of onion shampoo on MamaEarth’s website - Rs. 999. The same shampoo sells on Amazon for Rs. 843 (at the time of writing).

Another reason why brands have to underprice their products on platforms like Amazon is because they face punishment if they sell that same product elsewhere for cheaper. If a D2C founder lists a product on her own website for even 10% less than her Amazon listing price, her Amazon search rankings and discoverability will take a hit. Talk about tyranny of the platforms.

So what is the solution? And how the hell does ONDC actually work??

As the name suggests, ONDC is an open network designed for digital commerce. Buyers and sellers interact on this network via buyer apps and seller apps. A buyer app is basically a company that aggregates buyers (eg: PayTM). In theory, any payments app or banking app or telecom app or streaming app or social media app can be a buyer app. These apps are used by end customers like you and me who may be searching for goods and services to buy.

On the other hand, a seller app is a company or entity aggregating sellers. The job of this seller app is to help sellers digitise their product catalogues, upload the catalogues to the network, and facilitate the sale of these items online. A large company like ITC or HUL, or a large retailer like DMart, can also make their own individual seller apps. An example of a seller app could be a company that goes and helps a local vada pav stall to start accepting online orders (kind of like what Swiggy does, without the customer acquisition part).

Let’s explore how ONDC works by traversing the workflow of a hypothetical e-commerce transaction (some of these terms might be unfamiliar, but it actually isn’t that complicated once you see one of these processes end to end).

Imagine for a second that Rajinikanth is visiting Bombay and he really wants to order a cheese vada pav from a local stall to his hotel room.

The first thing that happens is that Rajinikanth goes onto his registered buyer app - say PayTM - and starts searching for vada pav (Step 1 in the below diagram). At this point, PayTM takes his search request and sends it to a kind of public registry known as an ONDC Gateway (step 2).

The Gateway is responsible for taking the buyer app’s request and broadcasting it to all the relevant seller apps in the network. I stress relevant because it won’t make much sense to ask a shoe store or radio maker if they happen to have vada pav. That sort of request is only likely to be fulfilled by food and beverage sellers. The Gateway knows which seller apps serve this category (step 3), so it knows exactly which seller apps to broadcast the search to (step 4).

Our hypothetical vada pav-focused seller app does operate in the food and beverage category, so it will receive the Gateway’s broadcast. The seller app will then check the internal catalogues it has gathered from its sellers - all the independent vada pav stalls (and any other restaurants it has onboarded) - to check whether any of those catalogues contain cheese vada pav ie. the item searched for by the user (this is step 5).

After checking and seeing that a couple of stalls do indeed sell cheese vada pav, the seller app will take the relevant information about the items - including details such as the names of the sellers, prices, images, descriptions, and stall locations - and send it back to the Gateway (step 6).

In this way, search results from all the sellers that possess cheese vada pav will be passed back to the Gateway. The Gateway collates all of these responses and shares them with the buyer app, PayTM (step 7).

Back on Rajinikanth’s screen, he is able to browse all the different options shown to him from all the different sellers who responded to his search (step 8). When he eventually zeroes in on the particular cheese vada pav he wants to order (taking into account proximity, price, images, and even user ratings), he clicks “add to cart” and begins his checkout process.

At this stage, something interesting happens behind the hood - the Gateway steps out of the picture after connecting the buyer app and seller app. This allows the buyer and seller to complete the transaction directly with each other, taking into account details like discounts, payments, delivery, tracking etc.

In this way, ONDC offers a hybrid marketplace model that cherry picks the good parts of both the platform model and the direct selling model, while simultaneously solving many of the problems with both approaches.

Wait, what problems is it solving exactly?

Let’s break it down:

The fee problem: Platforms like Swiggy charge restaurants 20-30% per order (and often even more), and they also make restaurants pay for ads to get a good listing on the Swiggy app. The reason this flies today is because the platforms perform all key functions for the sellers (i.e. discovery, order, fulfilment), including the most valuable function of them all - bringing in the customers. Using ONDC, sellers are able to source demand from customers across any and all buyer apps on the network, so no single buyer app is in a position of dominance over the seller. So while buyer apps and seller apps still charge a commission from sellers on ONDC, the size of the commission is currently 25-50% cheaper than it is on existing dominant platforms.

The selection problem: The biggest problem facing buyers on platforms is that they don’t necessarily see all the offers they can get. Through ONDC, a buyer can discover all relevant sellers that have been onboarded onto the network (via seller apps) and get multiple offers and options for the products they are searching for. Since there are multiple seller apps representing multiple sellers, the buyers have far more choice than if they were just browsing on a single platform. It’s like searching for a Coke on Amazon and getting all the listings for Coke on Swiggy, Bigbasket, and Zepto as well. Buyers can also exercise different criteria when making their selection - like proximity, user rating, discount - instead of being influenced by the heavy hand of advertising (which ONDC does not intend to allow).

The cold-start problem: The biggest problem facing a company that wants to create a new marketplace of any kind is the cold-start problem. How will an entrepreneur setting up a new marketplace for local pickles convince the picklemakers to work with him if he has no customers to purchase their pickles? How will he convince pickle aficionados to buy from his marketplace if the selection of pickles is paltry? Thanks to ONDC, this problem goes away. The entrepreneur can just onboard the pickle sellers and plug their catalogue into ONDC to start receiving demand from all the buyer apps on the network. By decoupling the demand and supply side, ONDC makes it feasible to build lots of different things that were previously too onerous because of the chicken-and-egg nature of getting supply and demand onboard together.

The lock-in problem: On platforms, the seller’s entire communication flow, data, and history is at the mercy of the platform. Whenever the platform wants, it can cut a seller off and prevent them from accessing those customers and reviews/ratings. In the ONDC model, the demand-side (i.e. the end customers) is totally different from the supply-side. If a seller is unhappy with their seller app, they can just switch over to another seller app. Since both seller apps are linked to all buyer apps via the Gateway, the set of end customers on the second seller app will be exactly the same as the first one.

As friend of the newsletter

puts it “Before ONDC you had to approach the large island of Hawaii and be at the mercy of the dictator of Hawaii – now you can approach an archipelago of islands to find a home. You have options.”The multiple-connection problem: As we saw earlier, selling directly to buyers has many benefits for sellers. However, the downside is the need to maintain multiple different connections to different buyers. ONDC solves this problem by getting sellers to maintain just one connection to the ONDC network. Through that single connection, they can get access to all the buyers on the network without having to manage multiple issues.

Wait a second, how is it just one single connection? Don’t the seller apps connect directly to the buyer apps once the Gateway has helped them discover each other? Doesn’t that mean there’s…many connections?

You are correct - the seller apps and buyer apps do connect directly. And in theory, managing custom connections like that with loads of different parties would ordinarily be a nightmare. But this is where the magic of ONDC really shines through.

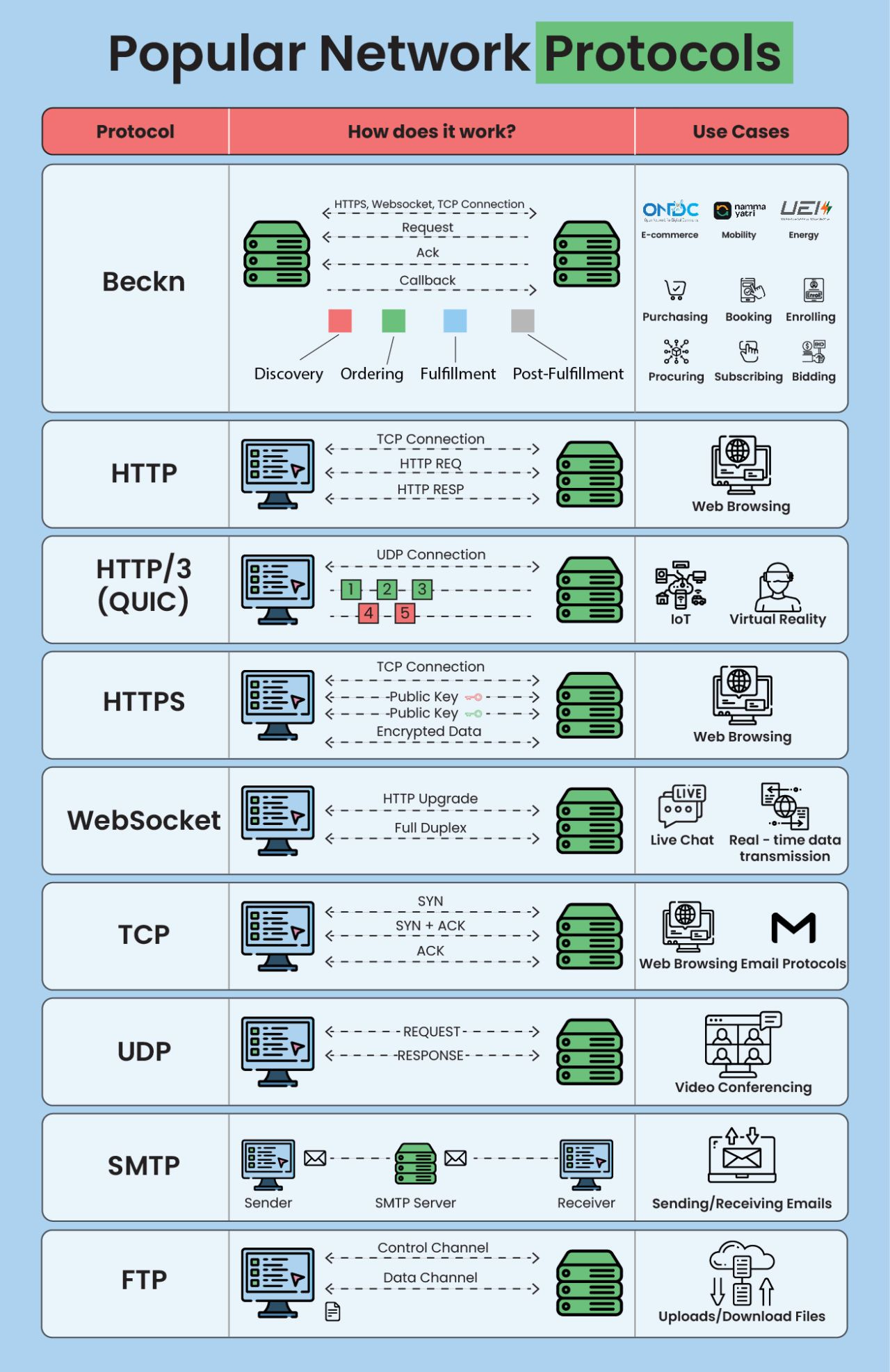

You see, ONDC is built on a computer protocol called the Beckn protocol. This protocol is what allows buyers and sellers to communicate seamlessly, and it is the secret sauce behind ONDC.

As a refresher, a protocol is a set of shared rules and standards that can be adopted by different parties so that they can achieve some shared goal in a seamless manner. Sign language, for example, can be considered a protocol. Any two people who master the shared rules of sign language can communicate with each other without needing anything else.

In the world of computing, protocols are very useful. Bluetooth is a protocol that allows data to be transferred seamlessly between different devices made by different companies using different operating systems. The Internet is based on a protocol called the Internet Protocol that allows different machines to communicate globally. Emails are also governed by a protocol called SMTP (Simple Mail Transfer Protocol) - this is what allows you to use your Gmail account to exchange emails with your boss who uses Outlook or your weird cousin who still uses hotmail. They’re all built on top of SMTP.

The interoperability inherent in these protocols is what allows the Internet to be the Internet. It’s what allows different browsers, applications, and websites to communicate seamlessly with each other - because at the end of the day they might be saying different things but they’re all speaking the same language.

The Beckn protocol - made and conceived in India - is an ambitious attempt to develop a universal language of digital commerce. It is a system that allows any two machines to use the same vocabulary when it comes to understanding the nuances of a commercial transaction. Fundamentally, by creating a common ground for commercial communication, it aims to connect people who want something with people who have something.

At its core, Beckn reduces the elements of a commercial transaction into ten discrete steps via technical processes called APIs:

Search: You need to begin a transaction by searching for the good or service you want to purchase

Select: You then need to select the items you want to buy

Init: Then you initialise an order by providing billing or shipping details

Confirm: Confirm an order by agreeing to terms and conditions and completing payment

Status: Get the status of an order

Track: Track an active order:

Cancel: Cancel an order

Update: Update an order

Rating: Provide feedback on a service

Support: Contact support

Between them, these APIs cover every phase of the transaction lifecycle from discovery, ordering, fulfilment, and post-fulfilment. The authors of the Beckn protocol go to great lengths to create a standard for each of these steps that is abstract enough that it can be applied to any industry and use case.

For example, the search API has specific details that inform both buyers and sellers how information should be exchanged when a user wants to search for an item. Provided all the buyer apps and seller apps implement the protocol correctly, any buyer app should be able to search for items across any seller app in the network. It is the same for each of the other nine steps as well.

To top it all off, the protocol also defines standards for how to represent objects or concepts that may be used in an online transaction. These are known as schemas. For instance, every single transaction will feature some kind of item that is being searched for or changing hands. Beckn takes this abstract idea of an Item and gives it a specific form:

Beckn defines core schemas for dozens and dozens of objects and concepts, from abstract concepts like intents to specific objects like vehicles. Furthermore, these schemas can be continuously evolved or adapted for different domains. So you can have specific schemas for concepts in the healthcare industry, or financial services, or even energy.

Together with the APIs, these schemas cover pretty much every conceivable step or component of the digital transaction workflow. Any two parties that implement all the Beckn protocol specifications can therefore communicate perfectly with one another without requiring any customisation or bespoke integrations. They work together seamlessly because they all speak the same language of Beckn.

This is what allows buyer apps and seller apps on ONDC to seamlessly connect with each other without needing any custom connections.

But wait a second, who handles the delivery of the product? Aren’t we talking about the actual physical movement of goods?

Totally correct. When the item being exchanged is purely digital (eg: buying a digital movie ticket), the workflow is very simple, but ONDC (via Beckn) has a solution for physical deliveries too. The solution is to turn the delivery part of the transaction into its own mini-transaction between buyers and sellers.

Let us return to Rajinikanth, who we have briefly left forlorn in his hotel room fantasising about his still-to-arrive cheese vada pav.

After he selects the item of his choice on PayTM (i.e. the buyer app), he will be offered a number of delivery options and asked to select one that appeals to him. Behind the scenes, this offering of delivery options is happening because multiple logistics providers have signed up to ONDC in a special category called logistics service sellers. So when Rajinikanth selects a vada pav to order, the buyer app makes another request to the relevant logistics sellers in the network to ask them if they can service Rajinikanth’s order. These logistics sellers respond with their best estimates of price, delivery time, and other relevant details.

So in a sense, there are two transactions happening at the same time. One is a transaction with the vada pav stall, and the second is a separate transaction with the logistics provider who will deliver the final item. To Rajinikanth, this all just seems like one continuous order flow, but at the backend, there is live bidding and competition happening amongst different providers of delivery services in real time.

Furthermore, the same principle can also be applied to other segments of the transaction workflow. Just like how logistics providers can bid to deliver orders, the protocol also makes provisions to allow specialised players to offer other ancillary services like customer support, grievance redressal, payment reconciliation, credit, insurance etc.

So on ONDC - because of the magic of Beckn - you could have a different entity handling the search phase, the ordering phase, the fulfilment phase, and the post-fulfilment phase of one single order.

All these disparate services can be seamlessly orchestrated together because they have all integrated the Beckn protocol - they are all part of the same network. They are all speaking the same language of digital commerce.

Woah, sounds like Beckn is a pretty radical idea.

It is certainly not what you would call unimaginative or conservative.

In fact, the concept of creating a generalisable protocol that can govern all digital commerce is a pretty wild idea. But India’s repeated success at pulling off ambitious ideas should give pause to the sceptics.

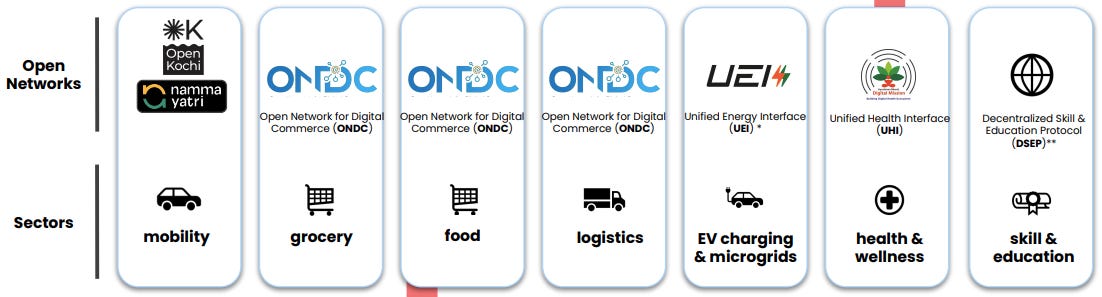

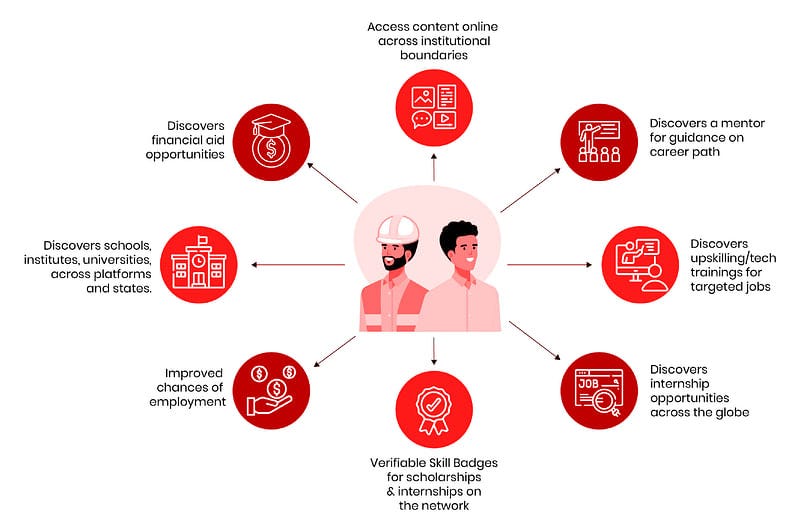

In fact, in India, Beckn is already being applied in a number of different contexts outside of commerce. These initiatives add credence to the idea that Beckn can work - whether you’re trying to order a sev puri, book a doctor’s appointment, apply for a job, or find an EV charging station.

Going a step further, the difference between Beckn and our other DPI efforts is that, if it succeeds in capturing global imagination and attention, the impact of Beckn won’t just be felt in India.

“…What few people realise is that India has built a protocol that can reshape global e-commerce. In this case, it is the Beckn Protocol that could be one of the most important technological contributions to emerge out of India in a long time.”

- Venkatesh Hariharan (Co-Chair of T20 Taskforce on Digital Public Infrastructure)

The Beckn protocol itself has no national allegiance. It is just a set of open source, publicly available specs and standards. That means that any country in the world can use it to spin up their own commercial networks. And they have:

the west African nation of Gambia has launched a country-wide open network initiative modelled on ONDC to connect local buyers and sellers.

the Amazonian city of Belem in Brazil launched a city-wide open network initiative, Rede Belem Aberta (Belem open network), to digitally connect skill seekers and skilling service providers in the city.

various civic authorities and transport departments in European cities like Paris, Amsterdam and Zurich are looking to adopt Beckn to construct local interoperable mobility networks.

As one ecosystem participant declared - “Every country would rather have its own communities come together to build a commercial network instead of letting foreign monopolies come and dominate their digital economies.”

These are early days, but you can start to envision a compelling future vision where different national and international networks can communicate with each other seamlessly because they’re all built on top of the same Beckn-based foundation layer. It would mean the dissolving of artificial digital boundaries that have been erected by tech platforms in favour of a shared global digital universe.

“It’s like having a $100 trillion economy in your browser.”

- Faiz Mohammed, Engineering Lead at FIDE (formerly the Beckn Foundation)

The potentially unlimited economic canvas for Beckn presents an intriguing game theoretical conundrum for incumbents and insurgents alike (as Pramod Varma, the Chief Architect of Aadhaar, likes to say “everybody will use it or nobody will use it”). If UPI was able to catalyse such a gargantuan socioeconomic impact via just a handful of APIs for interoperable payments, what kind of impact could Beckn have via a handful of APIs for interoperable commerce? It is tempting to begin painting various fantastical future scenarios, but we’re probably getting ahead of ourselves again…

Okay let’s get back to ONDC.

Right, so as we were saying, ONDC - powered by the Beckn protocol - helps solve the fee problem, the selection problem, the cold-start problem, the lock-in problem, and the multiple-connection problem of e-commerce.

Is there anything it can’t solve?

……….

Sorry.

But a better question would be - what doesn’t ONDC solve?

Okay. What problem does ONDC not solve?

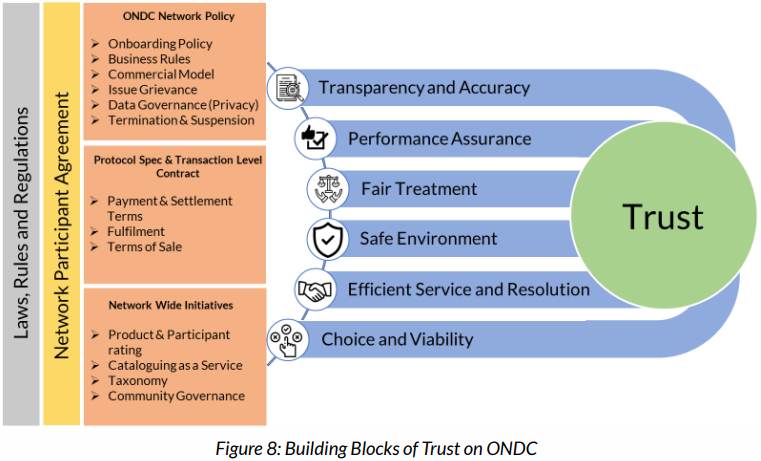

The problem of trust.

More than digitisation, more than efficient management of supply chains, maybe even more than bringing buyers and sellers together, the critical role of centralised platforms in e-commerce is to function as proxies for trust.

I don’t need to know the seller of the party-balloons I just bought on Amazon because I know Amazon will give me a refund if anything’s amiss (and vice versa). Same goes for Uber, whose neck is on the line if there’s a safety issue with one of their drivers. Same for Swiggy, who will instruct the restaurant to send over another pizza if the first one smells funky. Flipkart’s Binny Bansal, who basically laid the foundation stone for e-commerce in India, articulated this challenge on a recent podcast with Balaji Srinivasan:

“So we did these three things right - [brand, cash-on-delivery, and returns - all of which are like trust-building things]…it was very clear the job to be done was, for the brand, it was to build awareness and trust on these parameters. So to first build awareness that Flipkart is a place you can trust, Flipkart exists, you can buy books and electronics on Flipkart. The second was that you can trust Flipkart, that you can pay and if something goes wrong we’ll take care of you - 30 days no questions asked. So we created three spots - one on Cash on delivery, one on this 30 days returns policy and one just on the assortment that you can buy anything and everything under the sun.”

Trust is the oil that lubricates the rails of e-commerce. And perhaps the biggest challenge for ONDC is to figure out how to embed trust in a decentralised system. As you’ll find out in the last section, many of the issues that participants have faced in the early days of ONDC can be traced back to this issue.

Like what happens if a user cancels the order at the last minute? What happens if an item is damaged? What if there’s a technical issue with the network? What happens if the delivery agent messes up? What happens if an item is catalogued incorrectly? Would a buyer even want to go through the trouble of buying on ONDC if these risks aren’t addressed up front?

When there’s so many moving parts, and so many different cooks in the transactional kitchen, it’s hard to know who to blame if things go wrong.

Is it the buyer? The seller? The buyer app? The seller app? The logistics company?

How do you settle disputes? Who makes sure all payments are reconciled? Who takes the financial hit for an incomplete order? Who takes the reputational hit? Buyers only interface with buyer apps, and sellers only interface with seller apps, so what happens when a buyer is facing an issue because of some problem on the seller app end (and vice versa)?

Another friend of the newsletter Ria Mirchandani, ex-product lead at Whatsapp Payments, calls this the “one throat to choke” problem.

Central platforms are able to command and capture such a large chunk of the spoils of e-commerce because ultimately they are the one throat to choke. It is their neck, their brand, and their business on the line if anything goes wrong. This is what incentivises them to maintain the highest standard of service for each of their stakeholders. Buyers and sellers are willing to accept the problems with platforms (including the various costs) because the trust that comes with having one throat to choke is better than the stress of working with unknown counterparties.

Does ONDC have a plan for how they’re going to tackle this?

Yup, the proponents of ONDC have charted out an extensive roadmap of strategies, tactics, tools and techniques to combat the trust challenge.

This includes things like:

A network-wide provision for Online Dispute Resolution (ODR) and Issue and Grievance Management (IGM) [meaning that there will be a standard process of escalation for disputes on the network that extends all the way to legal arbitration]

A protocol-level module for rating and scoring participants that is built using a blockchain platform called CORD [English translation - buyers will be able to rate sellers (and vice versa), and those ratings will be captured at the network level. So, on the bright side, highly rated sellers will be able to transport their glowing reputation and scores to different seller apps. However, poorly rated sellers will have to carry that same poor rating to every seller app. There’s no hiding for them.]

Earmarking the role of a Reconciliation Service Provider (RSP) to streamline the settlement flow for multi-party payments [to address the unique challenge of reconciling payments not just between buyers and sellers, but between buyer apps and seller apps]

and more

On paper it would appear that the proponents of ONDC have thoughtfully laid the groundwork to address the trust challenges of an open network. Time will tell whether these mechanisms can help the network achieve the level of assuredness promised by centralised platforms. As we’ll cover below, ONDC saw over 6.5 million orders in January 2024 with 95%+ executed successfully. These are early days (before major scale kicks in), but the early results give credence to the idea that it is possible to foster trust in a decentralised system even without a singular throat to choke.

Back up just a second. You said proponents of ONDC. Who dat?

Great spot.

ONDC (the network) is being governed by ONDC (the organisation), which is a Section 8 non-profit company that is collectively owned by various governmental bodies and major financial institutions.

ONDC (the organisation) fulfils many of the same roles as entities like UIDAI, NPCI, and Sahamati, when it comes to the governance of their various DPI domains. It’s role is primarily to:

Register buyer apps and seller apps after vetting their legitimacy and making sure they understand the technical and operational requirements to function as part of the network

Manage the Gateway, which, as we’ve learned, is a piece of network infrastructure that helps to broadcast searches and responses from buyer apps and seller apps (the plan is to eventually allow other private players to spin up their own Gateways)

Help market and evangelise the network (including designing incentive programmes for network participants)

Ensure the technical upkeep of the network

Work with market participants to adapt and customise the ONDC protocol for new use cases (eg: B2B, Hotels, Electronics etc)

Stir up the ecosystem and build a community around ONDC both nationally and internationally

So far, they’ve done a great job to get the ball rolling. Now it’s up to the market to take the baton and run with it.

Right, so where are we now?

The cool part about doing a piece on ONDC now, is that you can basically make any reasonable claim you want about why it will or won’t be successful, and you’d be right. In other words, it’s early.

ONDC was first piloted in five Indian cities - Delhi NCR, Bengaluru, Bhopal, Shillong and Coimbatore - back in April 2022. The public beta was launched in September of the same year, and the network has been steadily growing and expanding across the country every month since then. There’s just enough activity and data now to start getting a picture of how things will shape up, but there’s still far more unknowns than knowns.

With that being said, I’ve been able to have close to a hundred conversations with participants from every corner of the ONDC ecosystem over the past four months (including several of the major protagonists). The anecdotal evidence from these conversations coupled with public data and news reports make for a decent sketch of the present ONDC chessboard.

So what does the chessboard look like?

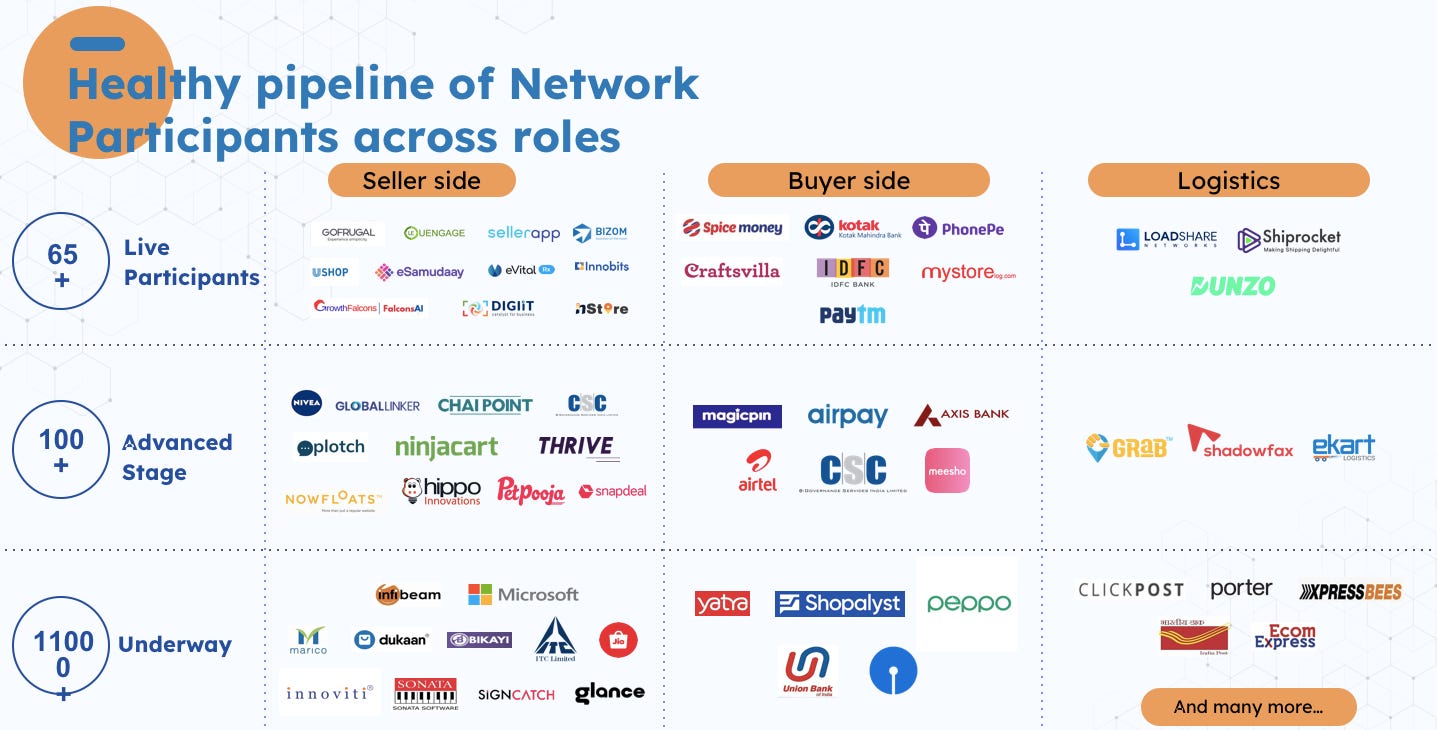

It’s buzzing. There’s a pretty diverse caste of participants that are either already live or in queue to join the network. This includes new startups, old startups, established enterprises, logistics companies, financial services companies, tech providers, and everything in between.

Because ONDC is ‘public’ infrastructure, there’s actually a neat feature on the official ONDC website that lets you search and keep track of the different participants that are live on the network (along with those that are in various stages of integration).

If you’ve ever hesitated before dressing up to head to a bar for a night out because you want to know “who else is gonna be there?” first, this database should help assuage some of that hesitation when it comes to joining the ONDC party.

On this portal you will find a potpourri of giant FMCG companies, popular DTC brands, buyer and seller apps, logistics players, banks, NBFCs, existing marketplaces, public tech companies, restaurants, retail stores, and miscellaneous service providers who’ve declared some form of ONDC intent.

At this point, if you haven’t entered the fray yet, you can either wait to hear back from the early entrants to see if the scene is any good, or you can wait till things have heated up properly before making your move, or you can get moving and try to get the party going yourself. All reasonable choices from where we’re sitting.

But are people actually using the network?

1. Well, in 2023, the number of monthly transactions on the network grew 2750x from a tiny base of 2000 in Jan ‘23 all the way to 5.5 million in Dec ‘23. The average daily transactions grew from ~50 per day to ~200,000 over the same period. That growth might seem impressive, but considering that Swiggy, Zomato, Amazon, and Ola each do ~1.5 million daily transactions in their respective markets, the ONDC numbers aren’t going to move the needle just yet.

2. The number of sellers on the network grew from 800 in Jan ‘23 to just under 90,000 by the end of the year. This includes brands and merchants that have set up their own shop directly on the network or are onboarding via third party seller apps. There were 26 live network participants at the start of last year (including buyer apps, seller apps and logistics providers). That number stands at 65 today, with over 15,000 participants at various stages of integration.

What are people buying?

Out of the 5.5 million transactions in December last year:

63% (~3.4 million) were in the mobility category

37% (~2 million) were in retail

Within the retail category:

32.5% were in food and beverages

29.6% were in fashion

12.6% were home and kitchen purchases

10.1% were grocery transactions

8.5% were for beauty and personal care products

5.7% were electronics purchases

Can you go a little deeper?

Sorry.

And yes, sure.

When reflecting on the adoption of ONDC in 2023, it’s useful to divide the quantum of transactions into Mobility and non-Mobility (AKA Retail) use cases.

Let’s start with mobility?

Mobility means anything that makes it easier for people to move around. It theoretically includes everything from ride hailing to bike sharing to public transport and travel services. It’s been one of the bright spots of the ONDC era.

New ONDC-based ride-hailing apps have sprung up all around the country in different constructs over the past 12 months (led by transport unions, new startups, groups of drivers etc). They’ve become a genuine threat to the duopoly of Uber and Ola. These ventures are encouched in the same thesis - that the current omnipotent platform model isn’t working for either drivers or riders anymore.

The lack of transparency over fees, caprice of surge pricing, frequent cancellation of rides, and lack of a voice in governance means that both drivers and riders are unsatisfied with the current set up of leading mobility platforms.

The protocol approach liberates drivers from having to pay 15-25% of their earnings to Uber/Ola. Instead, ONDC-based apps like Namma Yatri have chosen to work on a fixed subscription model where drivers pay ~Rs. 25 as a flat daily fee or Rs. 3.5 per trip (up to a maximum of Rs. 25 per day). This means that drivers take home 100% of the commission they make from each ride directly from their customers. So far this has led to a greater satisfaction from drivers that previously lamented their subservience to Uber/Ola. This, in turn, has created a more reliable supply of drivers in places like Bangalore and Kolkata, leading to more satisfied customers. The 12-month results of Namma Yatri speak for itself.

In many ways Mobility was ground zero for ONDC, considering that Beckn was first tested and proven as a concept with the Kochi Open Mobility Network (KOMN) in July 2021. Back then the KOMN helped to onboard various transport services and unions into a single portal to test the efficacy of this model. Fast forward three and a half year and the results of various open mobility initiatives present arguably the strongest case that ONDC won’t just be a flash in the pan.

What about retail?

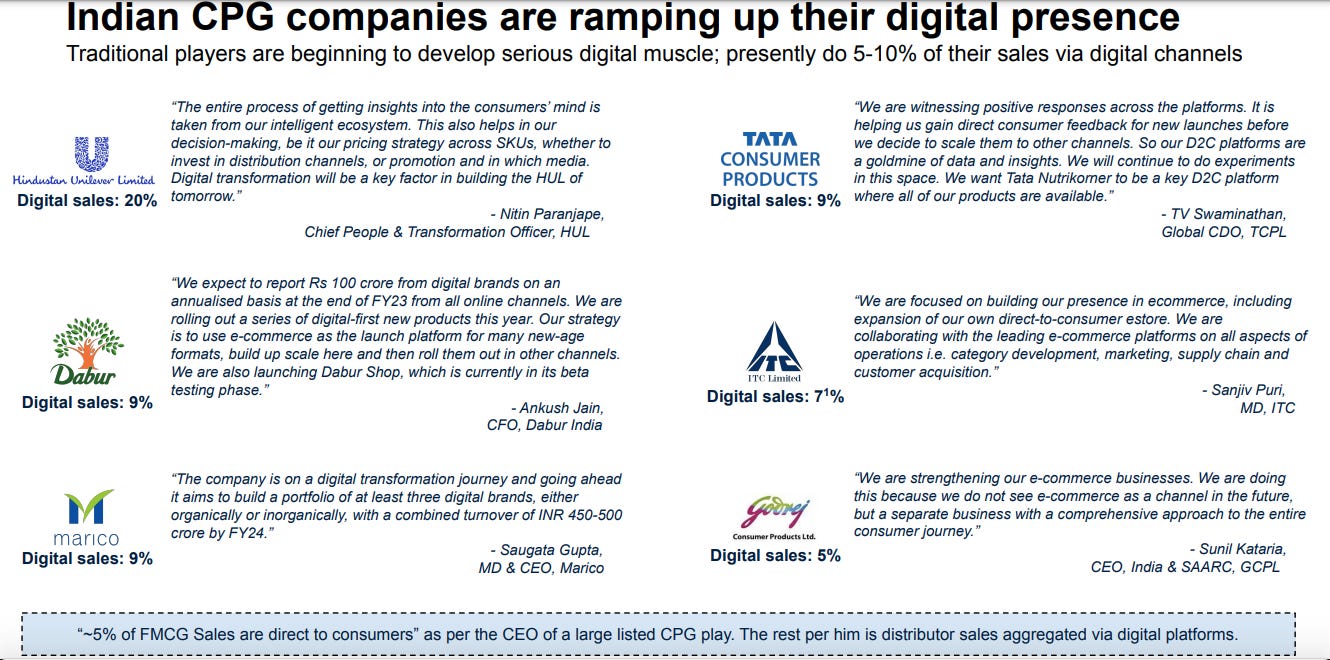

ONDC has steadily expanded the scope of its retail syllabus over the course of 2023. The original pilot was aimed at two major areas - Food & Beverages, and Groceries, largely because:

For F&B: on the buyer side, we have become exceedingly comfortable with the rigmarole of ordering food online. On the seller side, Indian restaurant owners are perpetually at odds with major food delivery platforms (like Zomato and Swiggy) because of their predilection for deep discounting and high commission rates (25-40%), and unilateral control over customer data.

For Groceries: on the buyer side, groceries (food, snacks, FMCG items, personal care products, fruits and vegetables etc) are a frequent daily purchase category accounting for 65% of retail consumption in India and 25-50% of monthly household spends. On the seller side, despite groceries contributing to over 20% of India’s GDP, it has only 1-2% of the overall share of India’s digital commerce market.

As more specialised seller apps have entered the fray (to onboard specific types and categories of sellers), the diversity of product categories on ONDC has expanded into things like fashion, electronics, home appliances, beauty and personal care etc. By October of last year there were more than 75 lakh SKUs available for sale on ONDC.

“…in few years time, every product or service which is relevant to a broad cross-section of users will make their product catalog visible in the open network using this open protocol, and diverse kinds of buying applications will come and help their relevant kinds of buyers to access the products relevant [to them].”

- T. Koshy (CEO - ONDC)

Is there anything you can’t buy on ONDC?

Love, respect, and admiration.

Just kidding (ish).

Jokes aside, while almost all the action in Year 1 (and a half) has centred around Retail and Mobility, ONDC hopes to stretch its limbs towards more exotic territory in the months and years to come. In theory, in a fantastical 100% successful scenario, there should be nothing you can’t buy on ONDC.

To illustrate: