At the time, Athens was a mobile society…In Socrates’ time, a champion wrestler became a well known philosopher. Playwrights and historians became generals, and generals historians. Poets became statesmen and politicians wrote plays. An architect might found a colony, and a man who made lamps might rule that city.

- Paul Johnson (Socrates: A Man for Our Times)

It’s hard to pinpoint exactly when a new trend enters the cultural bloodstream. In the startup world, occasionally a new trend will insert itself into the zeitgeist on the back of a genuine technological breakthrough - SaaS via cloud computing, crypto via public blockchains and smart contracts, cloud kitchens via food delivery apps (via smartphones), OTT platforms and live-streaming via 4G LTE, and so on.

The other side of that coin is engraved with tech trends that are largely the result of cognitive breakthroughs. They emerge from a reorientation, a reclassification, or a repackaging of prevailing behaviours into commercial verbiage that is more compelling (and more fashionable) than its constituent operations might suggest.

To name something is to breathe it into life. These psychological innovations allow us to get on the same page - to speak the same language when it comes to inventing, investing and understanding the New New Thing™ that’s currently afflicting the universe of venture capital and high growth tech. A shared vocabulary of startup memes speeds up comprehension on both sides of the investor-founder divide. Terms like ‘Web3’, ‘The Gig Economy’, ‘Uber-for-X’ and ‘Stripe-for-X’ are potent enough to cut across even the most indigenous of start-up dialects.

‘The Creator Economy’ is one such example of this brand of neologism that has demonstrated considerable stickiness. Originally coined by Stanford Professor Paul Saffo to describe the onset of the social media era, today it is the mantle bestowed on all the activities that comprise the business of attention in the digital age. It is the Holy Text(book) containing a multitude of equations that govern the relationship between time, money, audience and reputation on the Internet. It has spawned and legitimised a new professional class of mercurial entertainers and educators now commonly referred to as Creators. These are merchants of attention, typically embroiled in the trade of content creation on various social media platforms, hoping to extract economic value from their Internet fame.

The rechristening of social media to the ‘creator economy’ (or the ‘influencer economy’) in recent years has recast the perception of our online activity in the context of a digital bazaar. The sales pitch for this commercial arena is the promise that if you apply the correct force and time to the task of amassing an online audience, the odds of you being able to alchemise this social capital into financial capital are higher than they’ve ever been in all of human history.

For those who aren’t afraid to put themselves out there, for those who enjoy sharing their thoughts, their opinions and their expertise with the world, the Internet is an instrument of infinite leverage. It has bestowed every individual with the ability to ‘distribute’ themselves and their creative output to a global audience (re: a global market). Whether you’re an aspiring dancer, gamer, interviewer, writer, designer; whether you like gardening, stamp-collecting, competitive eating, Bengali poetry, or anime, today you can force your way into your chosen field via an Internet-illuminated path that didn’t exist before a time of permission-less media creation at a global scale.

Data Attention is the new oil. Or so they say.

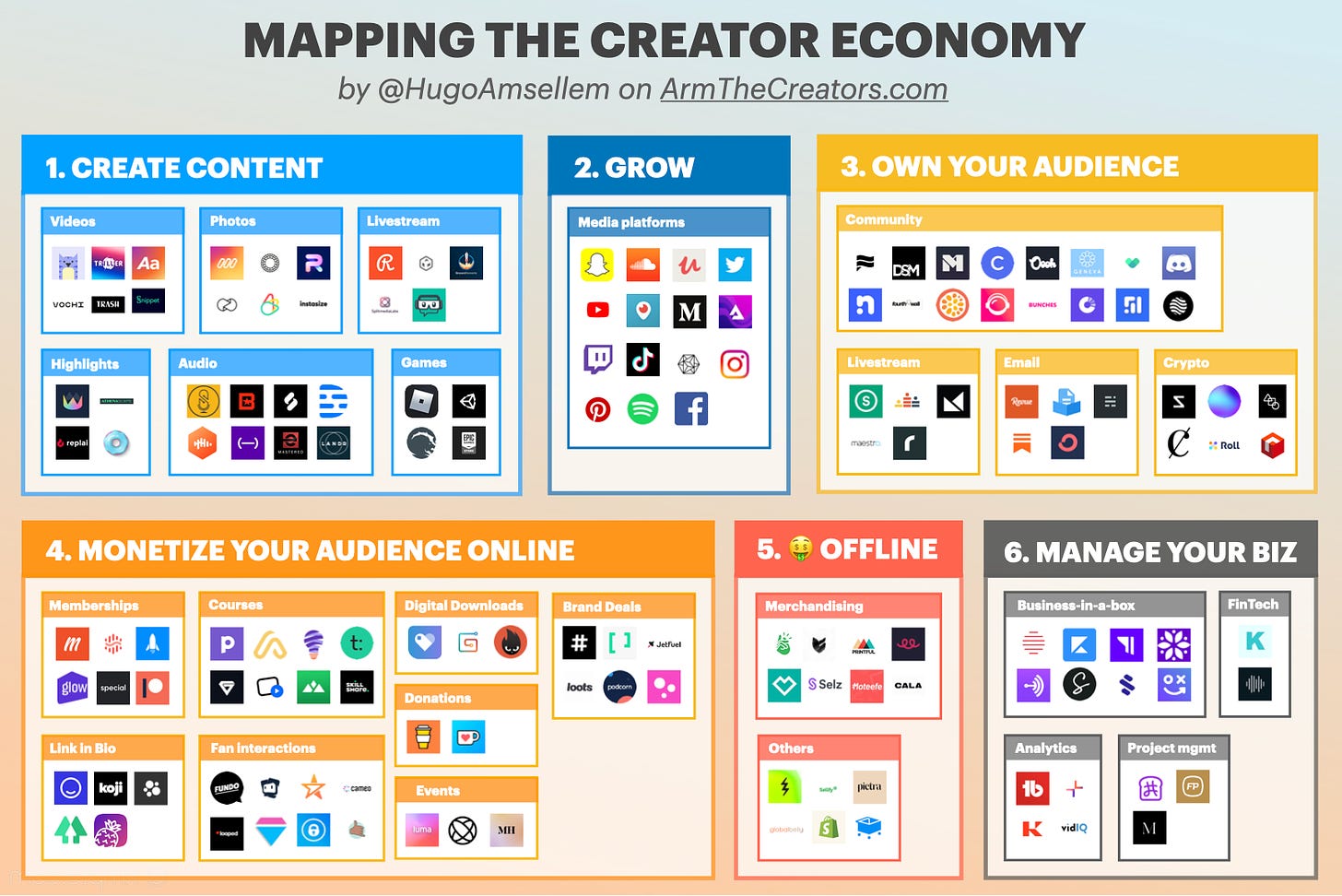

In the post-pandemic era, considerable digital ink (and VC funding) has been poured into willing this thesis into reality. Founders and investors alike have been busy trying to forge the most effective tools to arm the rebels, to help turn creator dreams into commercial reality.

I’ve found, however, that much of the pontification and (ironically) the attention around this space is far too constrained. News around the creator economy tends to either be mainstream media pieces written by curious observers casting an anthropological lens on what the hell those kooky kids are upto on TikTok. Or gossip focused on the affairs of the top 0.1% of creators that break into mainstream consciousness. Or thought leadership featuring glitzy numbers from VCs that are rationalising investments in creator tools and platforms. Or SEO-friendly blogs from advertisers preaching about the 10 Best Strategies For Influencer Marketing.

Much of the discourse is centred on the investable surface area of the creator economy - on the companies and platforms hoping to earn a fee by helping successful creators to professionalise their content, manage their operations, expand their product lines, engage with their community etc. It’s not hard to find content aimed at the spectators who have a financial interest in content creators. On the other hand, in my own experience, practical guidance for budding creators is harder to come by, especially for people that don’t know where to start or even how they should think about crafting an Internet career.

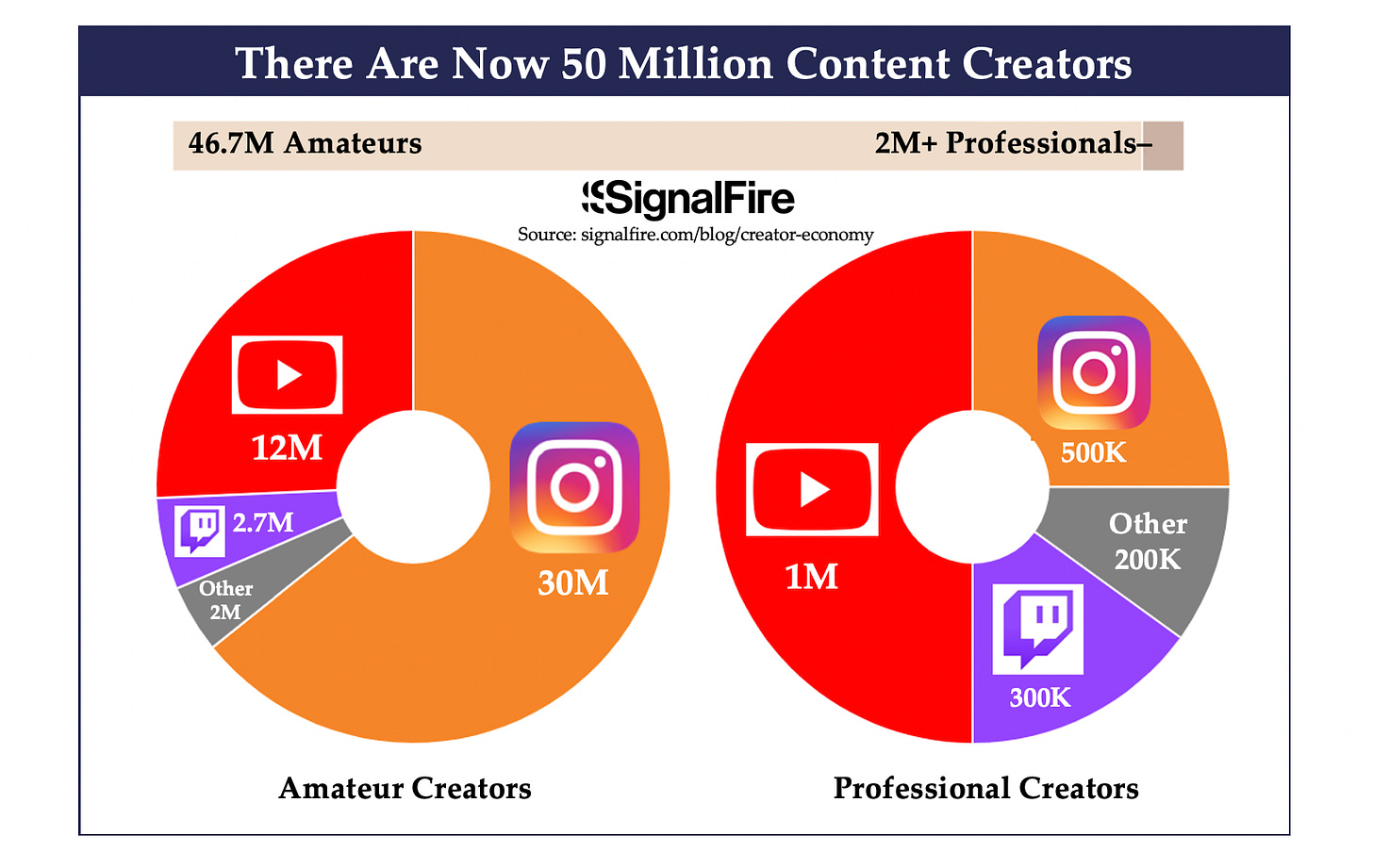

The spotlight tends to be on the Internet’s flashiest entertainers (and their economic gravity), as opposed to its aspiring performers. In my opinion, statistics like the estimated $100 billion market size for the creator economy, or $13.8 billion influencer marketing industry, are less interesting than numbers like these:

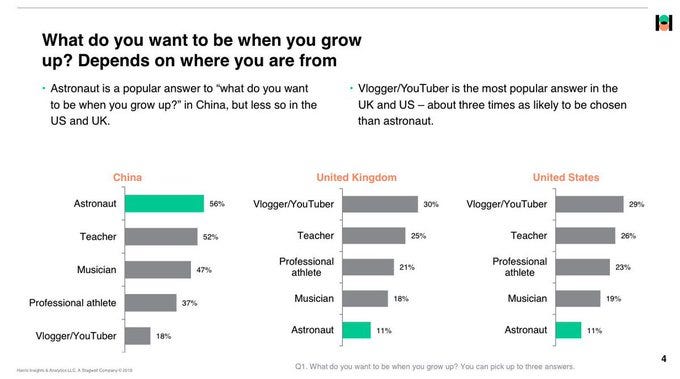

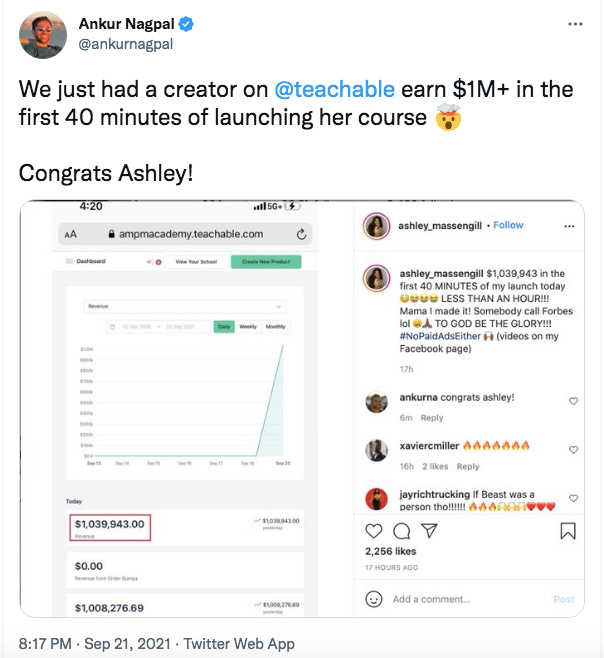

Or this:

Or this:

Or this:

Or that YPulse’s New Content Creators trend report found that a majority of young people already create content for an audience beyond their immediate family and friends.

It’s wild that in the course of a decade, content creation has emerged as a desirable career option seen at par with traditionally sexy careers like being a professional athlete, entertainer or musician. Let the record show that more kids today would rather be on Youtube than in space. There’s a truth about the nature of our society buried in there somewhere, but I’m not quite sure what it is yet.

Anyway, to me the coolest part about the creator economy is not that creators have multiple avenues to monetise their content (in reality the number of creators that actually earn a living wage from content creation is disappointingly low), but rather that so many young people want to be creators at all. And that content is seen both as an end as well as a means to an end when it comes to moulding one’s career goals.

The real story to me is less about creator monetisation and more about the Internet-enabled fluidity of careers anchored by content creation. I’m regularly blown away by the inventive ways individuals force their way into their chosen fields by blogging, vlogging, streaming, tweeting and posting about the things that interest them most. People are trying and testing their way to using content as a source of leverage, rather than a direct source of income.

It’s less of a Creator Economy and more of a Credential Emporium (trademark pending).

“Your CV is going to be a living, breathing thing that exists in real-time online, and that’s the way people are going to find you and hire you”– Jim O’Shaughnessy

I don’t think legacy institutions, particularly legacy education, is prepared for this shift. Try Googling ‘university degrees for content creation’ or ‘online courses for influencers’ or ‘how to start a Youtube career’ and you will encounter a sea of vapid corporate blogs and online courses that were probably outdated the moment they were conceived. The supporting ecosystem around creators is still relatively new and rapidly evolving, so it’s tough for traditional educators to provide an updated instruction manual to guide the next generation of creator-entrepreneurs.

For instance, 15 years ago if you wanted to break into the children’s toys industry, you might have had to earn a degree or two in engineering or design. You might have had to intern at a major toy company while at university. You’d probably need a few years of hands-on experience before you got the chance to spread your wings or attain a position of influence. On the other hand, Ryan Kaji has already brought in $30 million from his ‘Ryan’s Toys’ line of toys that he developed in partnership with Walmart in the United States. He’s 10 years old. He started his own Youtube channel called Ryan’s World with the help of his parents when he was five-years-old. Everyday he and his siblings make videos that feature reviews of popular toys, science experiments, skits and cartoons aimed for kids between 2-6 years old. His channel is one of the most watched on Youtube, with a subscriber base touching almost 34 million, earning him a spot as one of Youtube’s most highest earning creators.

Would anyone have told him all those years ago that his passion for making Youtube videos would help him break into the toy industry (notwithstanding the fact that he’d probably only just learned the alphabet)?

You could probably find millions of examples like Ryan’s, where savvy individuals have cashed in their natural charisma to amass influence (and build a brand) as a consequence of nurturing an audience within a specific niche. The Internet bestows individuals with the same reach and infrastructure that could previously be wielded only by the biggest brands, celebrities, and media networks. It’s logical that these individuals now enjoy the same perks that used to be exclusive to TV channels and radio stations, cricketers and Bollywood actors, with income streams that include advertising, sponsorship, subscription fees, product partnerships, merchandise etc.

We’re only beginning to test the limits of these new powers, which places us somewhere in the Palaeolithic era of Internet entrepreneurship.

“The internet is an ocean that we invent as we explore it” - Zero H.P. Lovecraft

From my own experience, the knowledge, the templates and the guidance to navigate these Internet-native career paths rest outside of university classrooms and on the Internet itself - in the brains of incumbent content creators who’ve ‘made it’ already, like David Perell’s Write of Passage course designed to help you “become a citizen of the Internet”, or Ninja’s Masterclass on how to become a successful streamer. The best people to learn from are the people who’ve done it already, or better yet, the people who are figuring it out and documenting their insights along the way.

I’m hoping to do the same.

When we launched this newsletter in the summer of 2020, we unwittingly threw ourselves into this world. We are now neither at the starting point nor the finish line of this journey, but iterating our way through Steps 2,3 and 4. I’ve found it useful to continuously document and revise my own thesis on this space, and especially to articulate the mandate of Content-Capitalism as I understand it.

Here’s how I think about what we’re building:

Tigerfeathers was intended to be an experiment to see what would happen if we allowed our writing to compound in one place. We’d spent some time working in different corners of the startup ecosystem as investors, entrepreneurs and operators. We enjoyed learning about tech, and recognised that writing publicly was a good way to unburden ourselves from ideas that were taking up room in our heads. If we did our jobs, we could help likeminded people to learn about the same things that we were nerding out over.

We had individually published the odd essay on Medium, but hadn’t given any thought to applying a concentrated effort in the same direction. At the time, newsletters had reinvigorated the discourse around the virtues of maintaining an email list of subscribers (particularly for journalists and bloggers). Platforms like Substack were laying out a compelling case for being connected directly with one’s readers, as opposed to being separated by the opaque curtain of ephemeral social media newsfeeds. Developing a long-term relationship with a loyal audience was seen as superior to having one-off flings with promiscuous readers.

With Tigerfeathers, we want to build a home for our writing on the Internet. A five-star library that people can visit whenever they want. Best case, if we put in the time and effort to faithfully maintain this cozy symposium, we might have a plot of digital real estate that is worth something to somebody someday.

I see this as the real directive of the ‘creator economy’.

It’s about building digital houses (but not in like a Metaverse-y way). It’s about making your corner of the Internet a place where people enjoy spending their time. Your Instagram page, your Youtube channel, your Twitter account, your Twitch stream, your podcast, your newsletter - your job as a Creator is to make your patch of pixels stand out from the crowd.

Two years ago, in my first piece for Tigerfeathers, I wrote that:

Every company is a media company (whether they know it or not).

The most valuable enterprise in ten years will be a media company.

The most valuable media company in ten years will be an individual.

Today I’d probably swap ‘media’ with ‘digital real estate’. If you consider yourself a worker in the creator economy, your objective is to create a compelling environment for strangers that wander into your vicinity. How you do that is up to you, and will depend on your individual personality, passions and prowess.

It is unfortunately the least explainable career path. On one hand, every creator is the founder of their own media company or media channel. On the other, they’re entrepreneurs building distribution channels for products that might not even exist yet, or leverage for ideas they haven’t even thought of yet. The simplest heuristic is to dump this vibrant mix of Internet-enabled vocations into a homogenous ‘influencer’ flavoured brew. This terminology unfairly strips out all the artistry from the profession in the interest of cold utilitarianism.

The mission of a creator can be difficult to fit into a concise job description, but I think the (slightly modified) Joker quote below does a decent job of summarising what you/we are trying to accomplish:

Because social media is still so new, we don’t really know what happens at the finish line. Like, what happens when top content creators today compound their audiences for as long as people have compounded their wealth? Where does the spectre of influence in society lie 20 years from now when Internet media completely subsumes all other forms of media, and Internet culture subsumes all other forms of culture? Will people see an online audience as a safety net the same way they do with college degrees? Are the best content creators simultaneously also the best teachers, the best entertainers and the best distribution channels for both consumer and enterprise products? Will all marketing be ~influencer~ marketing?

Is the creator economy just the canary in the coal mine for an economic era where we see a broader separation of work from employment?

We don’t have answers to a lot of this stuff yet, which is why it can be tough to identify what’s work and what’s play, what’s art and what’s an advertisement, and what’s a career and what’s wasting-your-time-on-the-Internet today.

I’m confident that over the coming decade we’ll come up with a better vocabulary for *gestures unspecifically* all of this. We will find a better way to describe and support Internet-native entrepreneurship. For now, I think the creator economy is far too limiting. It’s more like the Internet economy, and creating is just credentialing. It’s establishing a proof-of-work for opportunities that are currently invisible.

In other words, welcome to the Credential Emporium (once again, trademark pending).