Hey folks👋

Welcome to the 87 new Tigerfeathers subscribers who’ve joined since our last piece.

If you’ve ever wanted to stick it to your boss (and get smarter about India), start here👇

Two weeks in a row. A new record for us. Almost double the old record. I don’t know if we’ll make it to three, but we’re heading in the right direction.

Anyway, today’s piece is a little different from our regular programming. Most of our work in the last three years has centred around what’s new in India - new startups, new policies, new tech. But for this week’s story we dug into the past. It’s the kind of piece we’re going to do more of going forward, one that surfaces timeless ideas and lessons from Indian business history, and Indian history more broadly.

This week we tell the story of Maggi Noodles.

Every kid in India grew up eating Maggi. But back in 1983, when Nestlé first launched the product in the Subcontinent, the company had to almost literally rip a hole in the space-time continuum to turn India into a noodle-loving nation.

Maggi was one of the first ever branded consumer products to be introduced in pre-liberalisation India. It was a time when the average Indian still thought of noodles as “alien pasta”. The unlikely success of Maggi came down to the marketing magic of Nestlé’s India team in the 1980s. On the 40th anniversary of it’s arrival on the Subcontinent, this piece felt like a fitting tribute.

As always, let us know what you think. And if you feel like this was a good way to spend your time, do us a solid and help spread the word.

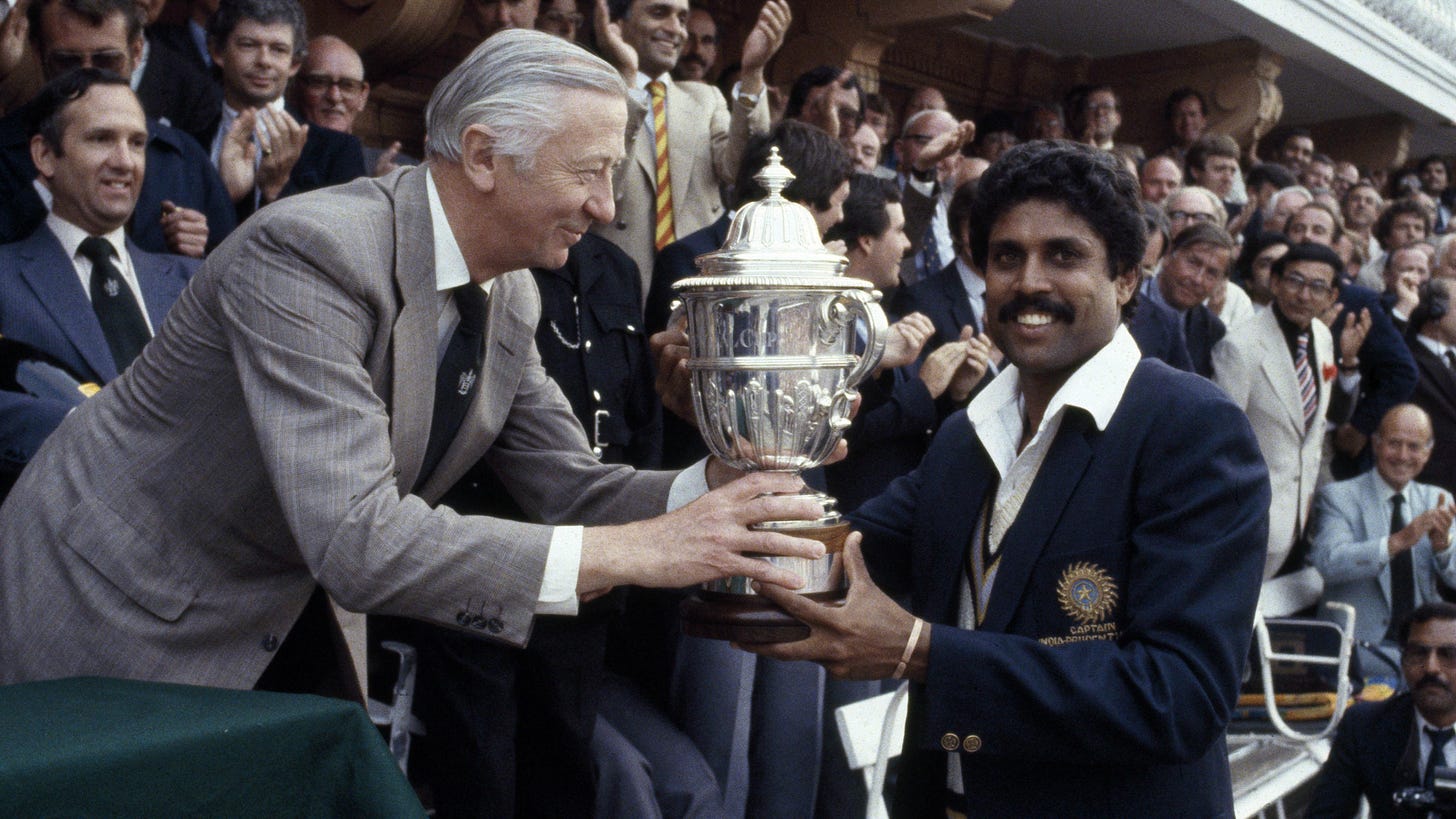

A sweep. A miss. An ambush.

By the time Kapil Dev and Mohinder Amarnath had mopped up the remnants of the West Indian tail-end, the Indian team had already made a mockery of pre-tournament prognostications about their chances of victory.

66-1 on India to win the 1983 Cricket World Cup. That was the official betting line offered by local bookies on the eve of the tournament. But Kapil Dev’s band of plucky underdogs hadn’t gotten the memo. They marched into Lord’s Cricket Ground on 25th June - into the Home of Cricket - and completed the ultimate smash and grab.

Leaning heavily on their bowling attack to defend a meagre batting total, India mustered a gritty performance oozing with intestinal fortitude, typified by Amarnath’s all-round excellence with the ball and bat. By the time the sun set on a sultry summer day at Lord’s, they had dished out a historic upset to an indomitable West Indies team that was coming off back-to-back World Cup wins. 36 years after wresting Independence from the British Crown, India had won its maiden World Cup on English soil.

For the generations that grew up watching the grainy images of India’s triumph on television, the World Cup was a touchstone moment. It was like witnessing the birth of Christ, in that it cemented cricket as an acceptable quasi-religion and cultural adhesive in India.

‘83 was also the first cricket event to be simultaneously telecast live for a pan-Indian audience (mainly in the latter stages of the tournament). The concurrent national broadcast added another dollop of monotheism to a young country that had inherited a buffet of reasons to feel disunited. Across its multitude of regions, religions, cultures and dialects, Indians in every tip of the Subcontinent could revel in the pride that came with being World Champions.

Unbeknownst at the time, six months before ‘Kapil’s Devils’ etched their names into cricketing folklore, 1983 had already played host to another iconic entry in the post-Independence history of India. Whereas the national cricket team galvanised the country around a single sporting contest, six months earlier an unlikely protagonist had begun to unite the country around a single snack.

In January of 1983, via a marketing blitzkrieg across the retail landscape in New Delhi, Nestlé introduced India to Maggi 2-Minute Noodles.

Known as instant noodles or ramen noodles everywhere else, these ‘2-Minute’ noodles would burrow deep into Indian hearts (and palates) over the next 40 years, ascending to hallowed status as the ‘third staple’ of Indian cuisine after wheat and rice. To orchestrate such a heady ascent, Nestlé couldn’t just settle for thinking outside the box with regards to its master plan for Maggi Noodles. In fact, the company had to discover a new box altogether, one that revealed a pristine surface of commercial attack in India i.e. the Z-Axis.

Curiously, this journey to culinary coronation didn’t start in the kitchens of Punjab or Karnataka, it originated in the fertile breadbasket of Kemptthal, Switzerland.

One Tastemaker To Rule Them All

Julius Maggi dreamed of ‘creating food products that would become as ubiquitous as salt and pepper’.

When he took over his father’s struggling Swiss flour mill in 1869, Switzerland was being remade in the image of the Industrial Revolution. Women were spending more time in factories and less time at home. It meant less time for cooking, either for themselves or their families. The Swiss government’s Public Welfare Society was concerned about the dwindling levels of nutrition in women’s diets, and the downstream effects of this on infant health and mortality.

Julius Maggi, ever the shrewd businessman, diverted the trajectory of his factories in search of an answer to this problem. After years of research, he developed a range of powdered flours, soups, and seasonings (most notably the bouillon cube) that were packed with legume-rich proteins. His products were designed for quick consumption and easy digestion.

Maggi products became the default nutritional accessories for Switzerland’s working population in the 19th century. On the back of his success, he set about building an enduring company around a range of industrial foods that were packaged for instant consumption (and didn’t compromise on taste) - a range that would eventually include Maggi’s famous Noodles.

Another Swiss multinational, Nestlé, would merge with Maggi in 1947 - the same year of India’s Independence. The reincarnated corporate heavyweight would set out to paint the kitchens of the world in Maggi’s famous ‘red and gold’.

In a remarkable feat of clairvoyance, Julius Maggi’s creations did indeed find their way onto dining tables across the world. However even he would have been surprised at how comfortably his Noodles would settle within the dimensions of the Indian dining table.

Maggiheads

For our international readers, Maggi Noodles (known locally just as ‘Maggi’) are to India what Coke is to the United States. It is less of a consumer good and more a bulwark of ubiquity and universality. It is not a product, but a paragon of comfort and consistency.

Like Coke, it is the flavour that hits just right (courtesy of a 20g sachet of seasoning called the ‘Tastemaker’, a potent mix of herbs and spices that converts a humble brick of noodles into a flavour rave designed for the Indian palate. Just add it to a pot of boiling water and two minutes later you’ll have a pot of gold). The Tastemaker has a 100% approval rating in a country that can be notoriously tribal when it comes to regional preferences around curries, masalas and batters.

Like Coke, you won’t get any side-eye for ordering a plate of Maggi either at home, at a highway rest stop, at a wedding after-party, or at a makeshift mountain-top restaurant in the midst of a raging blizzard. It can play every position from hangover cure to haute cuisine.

Like Coke, you can have it neat, or you can use it as a versatile dance partner for different accompaniments. In Maggi’s case that can mean vegetables, ketchup, cheese, eggs, nuts, sausages - almost anything goes. (I knew kids in school that used to melt milk chocolate bars into their bowls of Maggi. I’d ask them for a quote here but I assume they’re all in jail now).

For the most part, I’m referring above to Coke (the drink). But I could just as easily be referring to coke (the drug). India is addicted to Maggi.

In 2019, Indians consumed almost 264 million kilograms of 2-Minute noodles. Nestlé estimates that Maggi is eaten in 70% of all urban households in the country, with ~3.75 billion servings of instant noodles finding their way to Indian plates every year. In 2022, Maggi contributed Rs. 5627 crores (676.2M USD) to Nestlé India, which was 32.2% of its total revenue. At one point, it had cornered over 90% of the instant noodle market in India, a number that would even make Escobar blush…

…however, at the time of its launch in the early aughts, the odds of Maggi being successful in India were probably longer than our odds of winning the World Cup.

Unidentified Flying Noodle

The problem was that, in 1983, almost no one in India knew what the hell a noodle was. Besides a few corners of the North-East that had extended a cultural handshake to China and Nepal, noodles had no place in the diet of the average Indian. They were considered “alien” to the Indian palate, recalls Sangeeta Talwar - the former Nestlé India executive - in her book The Two-Minute Revolution: The Art of Growing Businesses.

‘Instant’ noodles were an even stranger proposition. India hadn’t yet been invaded by foreign snack brands. There wasn’t a vibrant consumer packaged goods industry. There were no supermarkets or potato chips.

For the most part, India was still coddled in the pernicious embrace of socialism (typified by the fact that you had to wait 20 years to get a landline phone installed in your home). There were severe restrictions on what could be produced, how much could be produced, and what could be imported. Retail shelf space was mostly occupied by commodity products that fit into the typical dal-roti-chawal-sabzi rotation of a typical middle-class household. Meals were nutritious, slow-cooked, and hot. Meal time was sacred - a chance for the whole family to get together and bond over home-cooked food.

The prospects of Indians lining up to swap their wholesome plates with the cold comfort of dehydrated ‘stringy pasta’ was slim. Talwar writes that:

“When it came to change, consumers were more comfortable changing the way they dressed than changing the food they ate. Food was deeply tradition-bound and varied considerably across states. Any brand that tried to alter this fundamentally would have to go through a real uphill climb, and probably not be successful.”

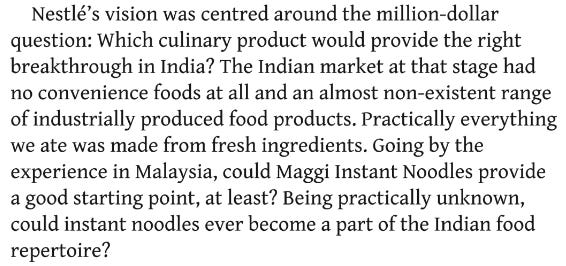

But Nestlé persisted. Partly they were seduced by the size of the Indian market. More importantly, they were emboldened by the launch of Maggi Instant Noodles in Malaysia in the 1970s. The product had become one of Nestlé’s top sellers in the region. At the time, 18 million Malaysians were consuming 20,000 tonnes of noodles every year. Noodles were already a staple in Malay cuisine before Nestlé came along, so it was easy for Maggi to slide in as a meal replacement within their existing dietary routines. That culture didn’t exist in India.

However, executives at Nestlé pushed on. They felt that India - with a similar similar demographic profile and rice-based culinary culture - would be open to the idea of instant noodles made from vegetable flour.

There was no data to suggest that Maggi Noodles would be successful in India (and no data about Indian eating habits at all). Nestlé’s involvement in India dated as far back as 1912, but they were mainly known for their dairy products, coffee and cereals. There was no existing brand equity they could cash in on with regards to the introduction of an instant noodle product. Supply chains would have to be built from scratch. Unorganised retailers and mom-and-pop stores would have to be convinced to give up valuable shelf space to stock an alien item that didn’t have a precedent in India.

Sangeeta Talwar and her team were going from zero-to-one. They had to reckon with several existential questions that each presented a formidable challenge to breaking into the Indian market, like:

Who was their ideal customer?

Could noodles ever break into the meal schedule of the average Indian?

Would Indian parents ever substitute the nutritious food they served at home for a packaged product?

How would they elbow their way onto retail shelves and into customer psyches?

The success of Maggi in India would come down to a refusal to settle for neat answers to hard questions.

An Earthbound Snack

After spending considerable time observing the daily food habits of Indians and understanding the patterns around meal time, Nestlé had found the epiphanies they were looking for. The proposition they settled on was that Maggi was “a quick-cooking, hot and freshly made snack, served with a mother’s love, to satisfy a child’s hunger”.

1. The Market

Nestlé realised that they had missed the mark by first attempting to target working women in India (the way Julius Maggi had done more than a century prior). The insight was that adults were apprehensive about trying new things when it came to their food. But kids weren’t. So Nestlé focused their communication around Maggi as a fun treat for children.

All their ads featured kids of a school-going age playing with their food, slurping, stretching and twirling the stringy strands of noodles in their bowl, and basically having a good time. They had figured out the recipients of their message. The next task was to figure out how to deliver that message.

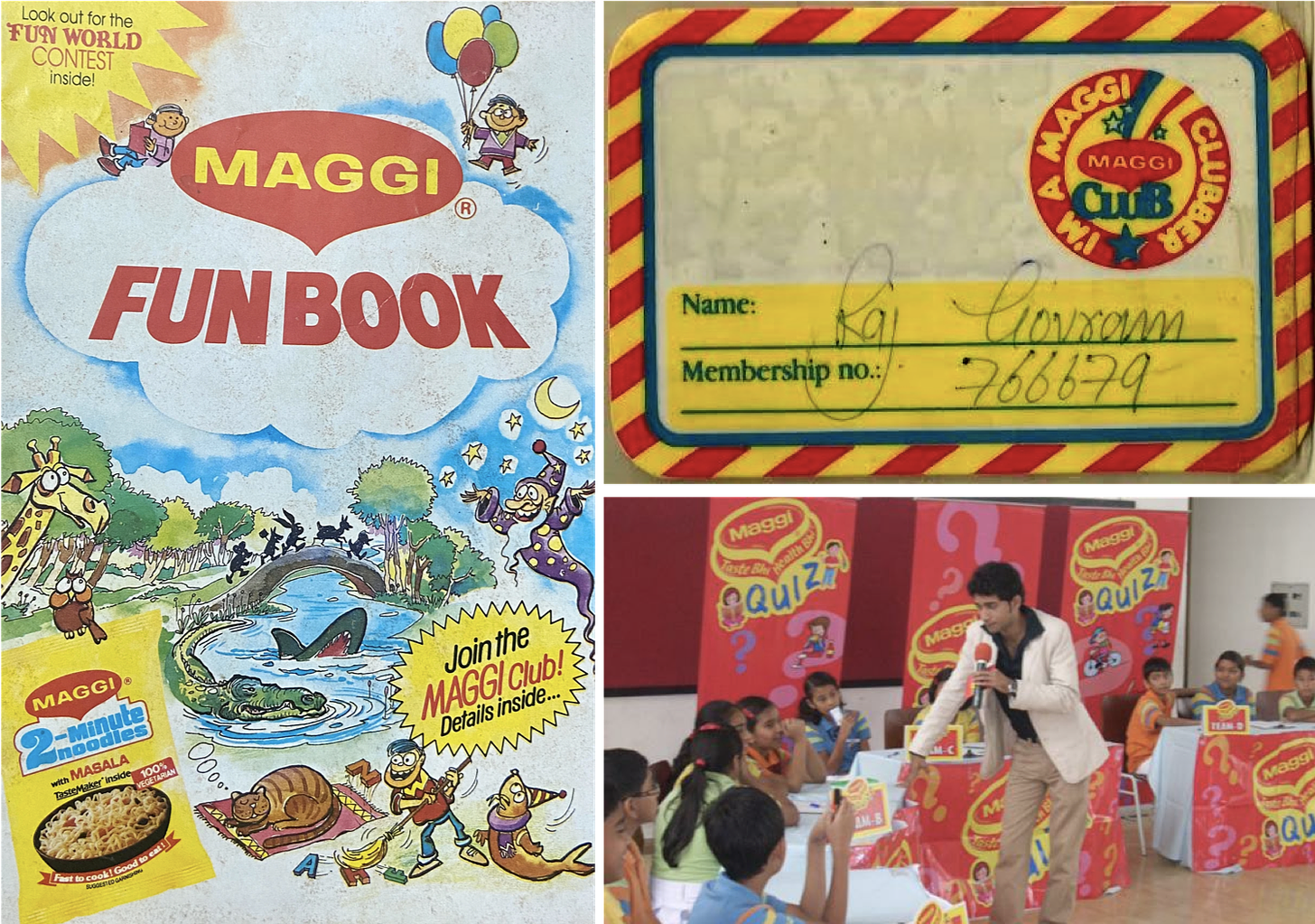

In 1983 India only had a single state-owned broadcaster. There was no Cartoon Network or Nickelodeon. Colour TV had only been introduced the year before in time for the Asian Games of 1982 (which were hosted by India). There wasn’t much of a reason for kids to sit in front of the TV. So Maggi had to find another way to reach their audience. So they went guerilla.

Ask any Indian kid that grew up in the 80s or 90s, they’ll tell you how prevalent Maggi was in their lives. Like the weird neighbourhood kid that always showed up unannounced, Maggi used to turn up at schools, cinemas and residential complexes, almost always bearing gifts. There were Maggi Clubs, Maggi Funbooks, and all manner of quizzes, prizes, games, and samples that ingratiated the brand in the minds of consumers. Maggi attached itself to the idea of *fun*.

2. The Time

Nestlé concluded that they had a very small chance of convincing Indian households to substitute their existing breakfast, lunch, and dinner options with a plate of noodles. So they skipped that battle all together, and decided to position themselves as a product for snack time.

They realised that people were less precious with their sensibilities and more adventurous with their diets when it came to snacking, open to indulging in food that was relatively unhealthy. Even though India didn’t have any established packaged snack products at the time, Indian households were familiar with traditional hot snacks like pakoras, idlis, samosas, upma, poha and pav bhaji that were made fresh in every home.

The advantage that Maggi presented was of a hot snack that only took ‘2-minutes’ to prepare. It still required *some* effort to make so Indian mothers didn’t feel like they were shortchanging their kids. The positioning also opened more occasions for indulgence - Maggi could be served as a tea time snack, it could be packaged in a school tiffin, it could be prepared quickly for hungry kids when they came home from school, it was a pre-dinner snack after they came home from games with their friends etc. Instead of needing to convince consumers that Maggi could be a full meal, it found a niche in-between meals.

3. The Communication

The Nestlé team made an astute call to avoid using the word ‘instant’ in their marketing. They reasoned that ‘instant’ could be conflated with ‘low effort’. It could also be misconstrued as junk food that was ready to unpack and eat (which it wasn’t). ‘Fast to Cook, Good to Eat’ became an enduring slogan.

‘2 Minute Noodles’ was a short, bold tagline that achieved the twin goals of communicating what the product was as well as its unique proposition. It also helped seed the idea that - because there was some cooking involved - Maggi could still be seen as a fresh meal. The added bonus was that they didn’t need to tweak or translate this tagline for each of India’s 28 official languages (and hundreds of local dialects). Everyone could understand ‘2 Minutes’.

Although the Nestlé team settled on children as their target market, they knew that mothers still had the final say on what their kids ate. The moms were the gatekeepers to their children’s diets. So every Maggi ad made sure to highlight the role of mothers in their kids’ lives. This made the product seem like a labour of love, as opposed to a lazy attempt to avoid cooking something from scratch.

Working mothers became Maggi allies (“Maggie Moms”), because it meant they only had to find ‘2 Minutes’ to prepare a fresh snack for their kids. And hungry kids knew that they only had to wait ‘2-Minutes’ to get a tasty treat. The ounce of delay gave them something to look forward to.

Nestlé was also savvy to depict bowls of Maggi decorated with vegetables in every TV ad and product pack. It helped to make the case that Maggi could still be a nutritious meal because mothers could smuggle vegetables into snack food. The ability to ‘customise’ a bowl of Maggi shrewdly signalled that there was still a role for mothers to play in the cooking process. (I’ve yet to meet a single person that actually puts peas and carrots in their Maggi. I assume they’re all busy with their juice cleanses).

4. The Place

“In the brick-and-mortar space, the shelf is the most critical spot - it is where the consumer comes in direct contact with your product; the moment of truth.”

- Sangeeta Talwar (The Two-Minute Revolution: The Art of Growing Businesses)

Maggi was the first ‘flexible package’ (soft pack) food product to be launched in India. Everything else came in a glass jar or tin. This caused several headaches for retailers and storekeepers.

For one, Maggi packets were an easy target for rats and pests in muggy storerooms. And two, it presented a challenge when it came to displaying Maggi inventory for customers to peruse. Coupled with the fact that instant noodles were suspicious to begin with, this gave mom-and-pop stores a reason to question whether the risk and opportunity cost of offering Maggi was worth the effort.

Nestlé developed an elegant solution that felled both those problems with a single haymaker. Retail stores at the time didn’t have much shelf space or lighting. These were largely hole-in-the-wall establishments run by a single omnipresent shopkeeper. Nestlé realised that instead of adding another strain to the limited surface display areas, they would invade the ‘air space’ instead. Inspired by a trip to Malaysia, they came up with the idea of using overhanging baskets to display packs of Maggi Noodles.

The use of these lightweight nets ticked off several boxes at once. For one, it placed Maggi at the eyesight level for customers - “Jo Dikhta Hai Woh Bikta Hai” - and also the shopkeepers, who could easily reach for packs of Maggi when customers asked. The baskets doubled as mini-billboards so the Maggi brand could feature prominently at any retail location. The simple innovation reduced decision fatigue for store owners, who didn’t need to worry about reserving valuable counter space for an unproven product. And it kept the inventory safe from the reach of ground dwelling pests and vermin.

It was probably the first instance of technological ingenuity implemented at the retail level in India.

“To convince shopkeepers to take time off their busy day and hang up a net with Maggi products in it, I got up on a stool myself and I showed them that if a woman in saree and high heels can do it, it’s easy and so can they.”

- Sangeeta Talwar (The Two-Minute Revolution: The Art of Growing Businesses)

The legacy of these floating baskets still lives on in corner shops around the country. Maggi had found a way into Indian trade, a territory they would hold dominion over for the next four decades.

Finding the Z-Axis

If “Xerox” is for Photocopiers, “Colgate” is for Toothpaste, then “Maggi” is for Noodles.

- Economic Times, 2003

Forty years later, Maggi has become a staple in every Indian kitchen. Maggi is mainstream - a category unto itself. The story of Maggi merits examination because it lays out the case for taking an unconventional approach to solving unconventional problems. Nestlé not only created a new food product in India but a new food category. Maggi Noodles became the ancestor to every packaged food product or branded snack or ready-to-cook meal that came after it.

Back in 1983, there were a million reasons why an instant noodle product wouldn’t be successful in India. If Nestlé had followed the same formula as the one they’d implemented in other parts of the world, they would not have found their target market (kids), they wouldn’t have identified their gatekeeper (mothers), they wouldn’t have known what product they were selling (snacks), and they wouldn’t have made it to retail shelves (via a hanging basket).

Ms. Talwar would remark in a later interview that “sometimes you need to fly with the birds…to get away from what is in order to be able to see what could be”.

The team at Nestlé had to literally fracture space and time to make Maggi a success. They had to find a slot for eating that was between our three traditional daily meals. They had to find a new plane of display that didn’t take up any existing visible surface at retail stores.

On a flat plane, they found a roundabout route of attack. Trapped between X and Y, they discovered a Z-Axis. The openness to see what ‘could be’ widened their river of potential winning ideas.

This kind of ‘Z-Axis’ thinking is more commonplace than you think. You can find trace amounts of it in the stories of all the companies and brands that zigged when they could have zagged. It’s about knowing what to look for. It typically takes the form of a ‘What if?’ question, ideally one that provokes a cognitive recalibration around a commercial target.

Airbnb began by asking ‘What if your home was a hotel room?’

Indian startup Glance began by asking ‘What if your phone lock-screen could be used as a surface of entertainment?’.

When Radiohead were releasing their masterpiece seventh studio album In Rainbows, the band asked ‘What if we let our fans pay whatever they wanted?’

The willingness to draw outside the lines greatly expands the scope of a given solution set. In the disco of the Z-Axis there is ample room to get busy on the dance floor. The flashing tiles reveal a set of answers that might have been previously invisible. It all starts by asking the right question.

What if there was a way to make it into retail stores without taking up any existing shelf space?

What if there was a set of customers that would find the idea of alien pasta appealing?

What if we could go to England and win the World Cup?

It can be tempting to spot four points and instantly label it a square. But if you squint really hard you might find that you’re looking at the outer edge of a cube that’s glowing with possibility. It’s easy to tell someone to think outside the box. Better advice would be to just notice the box.

"Aut inveniam viam aut faciam" (“I shall either find a way or make one")

- Hannibal

1983 has come to be remembered as a particularly sublime vintage in the post-Independence history of India. You would have done well for yourself by betting on Kapil Dev and Nestlé to get the job done. To sow a culture of winning and culture of snacking in a single trip around the sun is no mean feat. It’s a reminder that the odds are just the odds. The magic lies in between the lines.

Sources & Additional Reading

The Two-Minute Revolution: The Art of Growing Businesses by Sangeeta Talwar

The Magic of Maggi by Nestlé

hands down, the best thing iv read all month! kudos

Z-axis thinking ftw

Great article Rahul, very relatable to one growing up in 1980s, and good insight on Z axis . Has this been written for WOP ?