"Foundation": The Bold Bet On Moore's Law That Changed India's Destiny

The story of a software architecture decision that saved billions of dollars, millions of lives, and set the stage for a nation's prosperity.

Tigerbrethren, welcome back. 🐯🫡

A special shout-out to the 800 new subscribers who have joined us since our last piece - an interview with Anupam Gupta about the fascinating history of Asian Paints, India’s largest paints company.

The year was 2009. It was a biting winter evening in New Delhi, the kind of evening on which the cold seems to smother the city’s usual cacophony.

In Nandan Nilekani’s office, the silence was shattered by a phone call. On the line was Srikanth Nadhamuni, the project’s Head of Technology. His voice, tinged with panic, broke unwelcome news: “The experts say it can’t be done. We won’t be able to afford it.”

The "it" in question was Aadhaar, the world’s largest biometric ID system. A system unprecedented in scale, unparalleled in ambition, and now, it seemed, unattainable in reality.

Yet today, Aadhaar covers nearly the entire population of India and is the backbone of the country's digital revolution. It is arguably the most important and successful technology undertaking in India’s modern history.

How, then, did a project deemed impossible become the cornerstone of a nation? Why did the experts sound the death knell and how was this existential threat eventually overcome? What were the stakes behind Aadhaar’s success to begin with?

All these questions find their answer in this story. It is the story of Aadhaar, and a nation hungry to evolve. But it is also a human story - of a small group of dedicated public servants and trailblazing technologists who proved the experts wrong by betting big on the future of computing, and in the process, rewrote the destiny of the world’s largest democracy.

So fasten your seatbelts, because it’s a wild ride. But before we take off, a word about our sponsors.

This edition of Tigerfeathers is presented in partnership with… Finarkein Analytics.

Like some of our other essays, this Tigerfeathers story is concerned with how India marshalled Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) to remodel itself as the flag-bearer for 21st century development. That makes Finarkein Analytics a perfect partner for this piece.

Finarkein is a data analytics company that helps enterprises to publish, consume, and analyse data on India's open protocols and networks. They have played a role in advancing several of the industries and protocols we have covered in this newsletter, including OCEN, ONDC, Account Aggregators, Lending, Healthcare, and IndiaStack as a whole.

Finarkein’s contribution across these projects has varied in nature - in some cases, they have been involved in building technical standards from Day 1. In other instances, they have built community tools, data dashboards, and services that are crucial to the network (one such example being the authentication and token services that power the Account Aggregator ecosystem today).

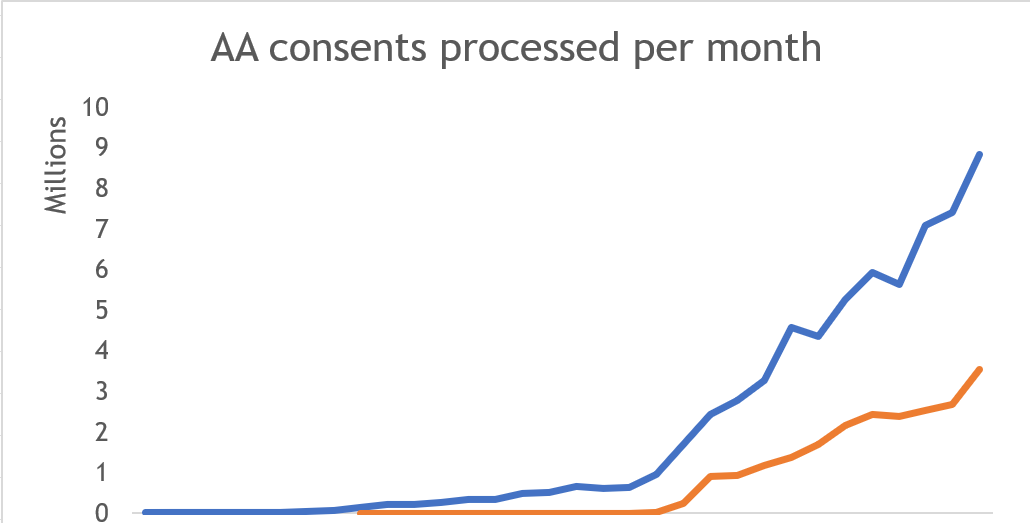

But the common thread that cuts across all of this is a willingness to deeply immerse themselves in the problem in order to help not only their customers, but also the ecosystem at large. Nobody can deny that they’ve put in their 10,000 hours of hard graft to build deep expertise in the field. It’s no wonder then that they currently drive almost half of all pan-India Account Aggregator volumes and a third of all flows on India’s emerging open healthcare protocol.

If you are a bank, lender, insurer, or startup looking to capitalise on the meteoric rise of India’s next-generation financial rails, Finarkein are your partners of choice. The same goes for companies seeking to build on top of ONDC or ABDM. Backed by some of India’s top investors (disclosure: including me), and trusted by over 50 of India’s largest BFSI enterprises, Finarkein is your one-stop shop for all things data and DPI.

Be sure to catch up with the founders next month at Global Fintech Fest (booth K24) or reach out to them at hello@finarkein.com. They’ll have you up and running with best-in-class data products and customer journeys before you can spell Tigerfeathers.

So, where does the story begin?

It begins in 2009, a time of transition.

The year kicks off with the massive Satyam accounting scandal. As confidence in the country’s corporate governance norms plummets, so does the Sensex, reaching its lowest point in three years. While the Indian economy doesn’t follow its global counterparts into formal recession, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) is forced to implement a second stimulus package to combat a national slowdown.

And though the trauma of the brutal 26/11 terror attacks of November 2008 has yet to heal, Maoist violence in the Red Corridor continues to fray the nerves - a painful reminder of the deep-seated socio-economic disparities plaguing the country. Corruption, that perennial thorn in India’s side, is the hot-button topic in both the public and the private sector.

But the most burning issue is poverty. Widespread, crushing poverty.

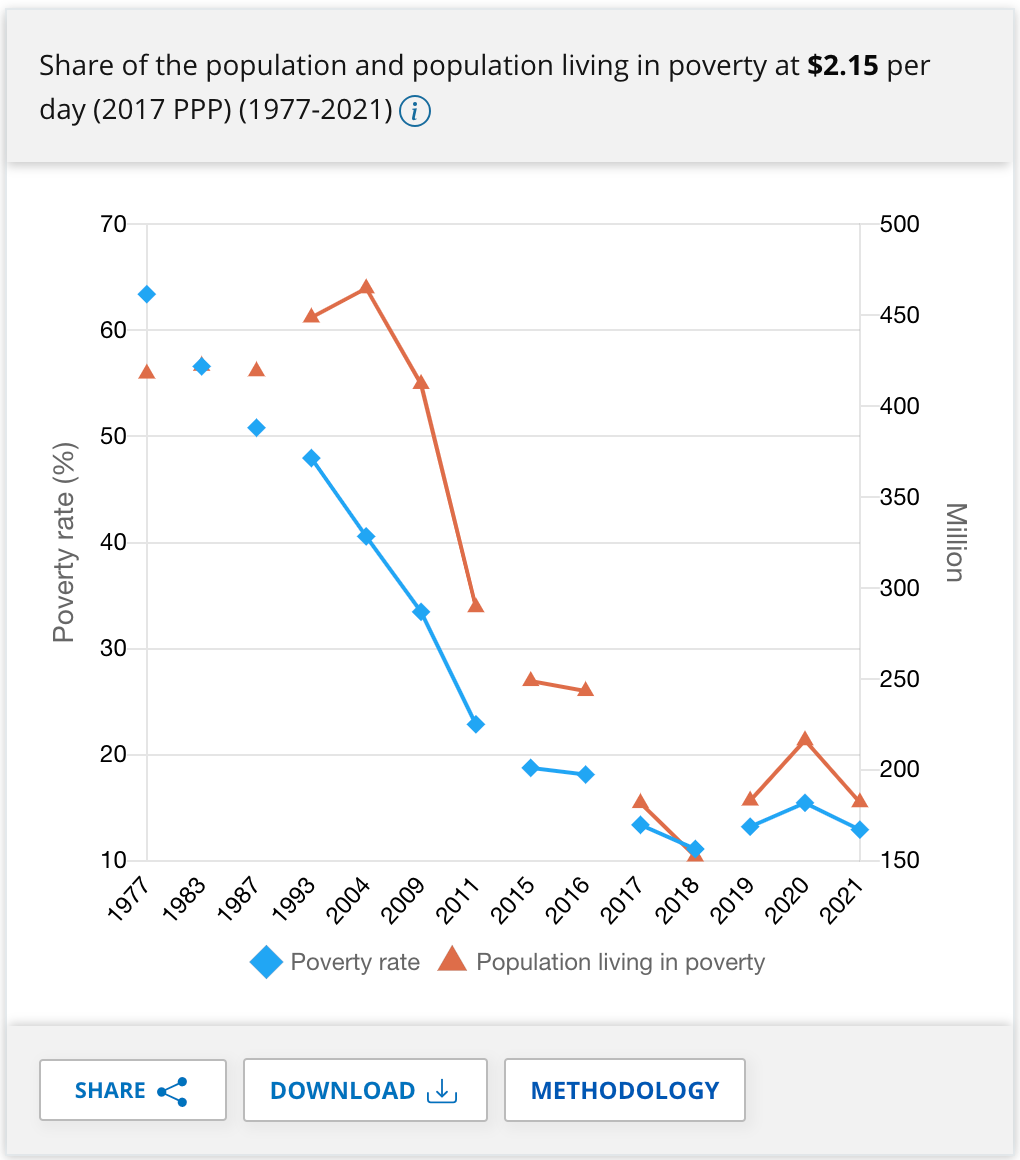

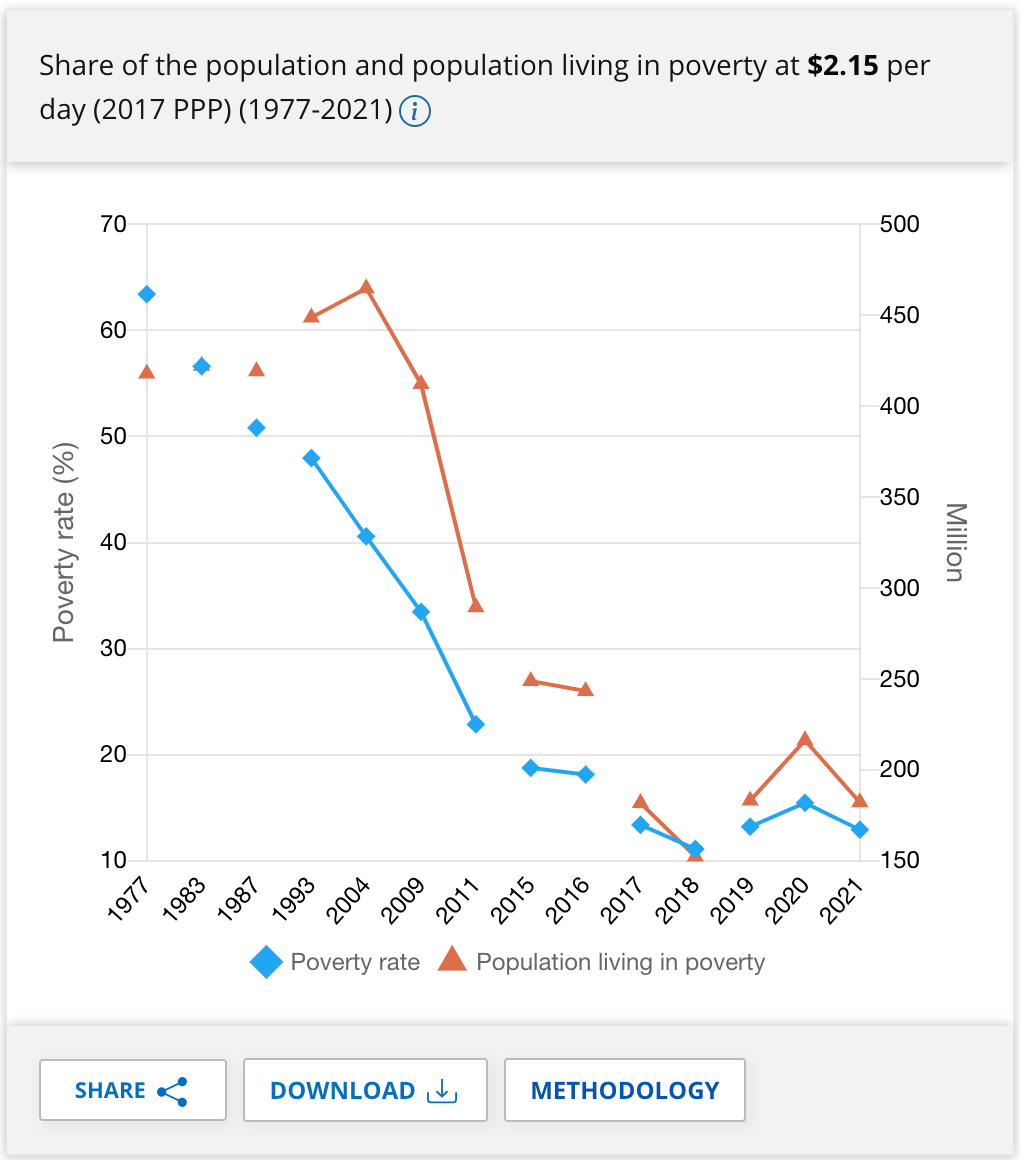

For the last 300 years of its long and proud history, India has been mired in penury. The numbers paint a stark picture. The World Bank estimates that in the 1970s, over 60% of Indians lived below the poverty line.

By 2009, after years of economic liberalisation and growth, this figure had only reduced to 33%. That still translated to over 300 million people – a population equal to that of the United States – struggling daily for the most basic necessities.

But numbers, cold and impersonal, fail to capture the human cost of this persistent poverty. They don't speak of the mother skipping meals to feed her children, or the farmer watching helplessly as his crops wither in a drought-stricken field. They don't convey the frustration of a young man, full of potential, unable to open a bank account for lack of proper identification.

These Indians were adrift in the deep ocean, and it was the government’s responsibility to throw them a lifeline. And as if it wasn’t already hard enough to provide social services to hundreds of millions of people, the problem was exacerbated by the fact that huge swathes of the population were essentially invisible to the bureaucratic machine.

What do you mean?

In 2009, 400 million people were estimated to lack a formal identity of ANY kind. Equally shockingly, only 17% of the entire adult population had a bank account.

Think about that for a second. Think about all the things that an identity allows us to do that we take for granted - getting a job, buying stocks, owning property, getting an Internet connection, traveling, entering into legal contracts. These most basic of freedoms are very hard to obtain without a legal identity.

Now think about how you - as the government of India - would figure out a way to deliver massive amounts of life-saving rations, welfare payments, and subsidies to a population of over one billion people in the absence of any efficient form of either identification or money transfer.

How do you ensure that subsidies reach the right person when that person, for all official purposes, doesn't exist? How do you prevent fraud in a system where ghost beneficiaries could outnumber the living?

Um… it seems difficult.

To put it mildly.

No wonder then, that Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi said in 1985 that “out of every rupee spent on welfare in India, only fifteen paise reaches the poor”. The rest was either pilfered away by thieves or squandered on wasteful delivery mechanisms.

Change was needed, and urgently. Not just incremental change either, but a moonshot – a bold, transformative idea that could drag the nation into the 21st century.

And so Aadhaar was the solution?

Yes. As early as 2001, various government committees and advisors were calling for the creation of a new identity system that could cover the entire population, tie together the sprawling expanse of existing welfare programs, and root out the issues of inefficiency and fraud. But the various proposals that were mooted never saw the light of day.

Eventually, in January 2009, the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) was established. Five months later, the highly respected Infosys co-founder Nandan Nilekani officially assumed the role of Chairman. High level bureaucrats such as Ram Sewak Sharma and K. Ganga joined the mission, along with several civic-minded technologists from the private sector who volunteered to be part of an extremely low-paying and high-difficulty project just so they could give back to the nation and be a part of something that Forbes India called ‘the world’s most ambitious project’. A quick look at the resumés of volunteers such as Srikanth Nadhamuni (board member, HDFC Bank), Raj Mashruwala (COO, TIBCO) , Viral Shah (inventor, Julia Lang), Vivek Raghavan (CEO, Sarvam AI), and Sanjay Jain (co-creator, Google MapMaker) drives home the high pedigree and quality of the private sector talent who joined the mission.

Several of the vignettes that emerge from this chimeric collaboration between the rigid world of government and the high flying world of tech are extremely fascinating, but the most interesting thing, for the purpose of setting up our story, are the results.

What sort of results?

Results even more amazing than that one 👆🏽.

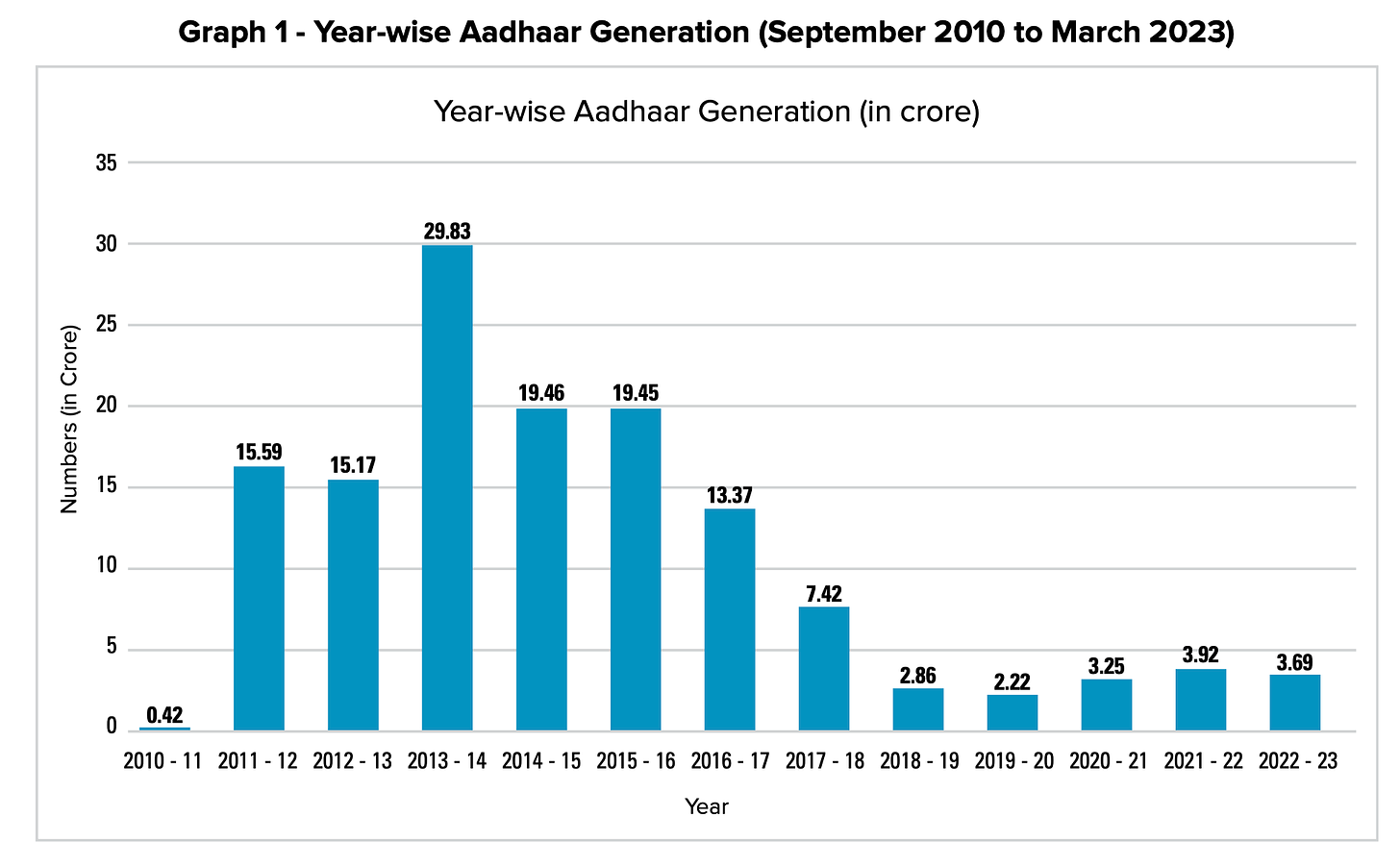

First and foremost came the issue of coverage. The first Aadhaar number ever was issued in September 2010 to a woman in Maharashtra. Over the next 5 years, around one billion more Indians would be issued a unique 12-digit Aadhaar number.

Today, there are more than 1.4 billion Aadhaar numbers in UIDAI’s Centralised Identities Data Repository (CIDR), covering 99.9% of the adult population.

Let that sink in for a moment. In less time than it takes for a child to complete elementary school, India had given digital identities to more people than the populations of North and South America combined.

But Aadhaar was never meant to be just a massive database. Its true power lay in its ability to transform India's economic landscape, particularly in the realm of financial inclusion.

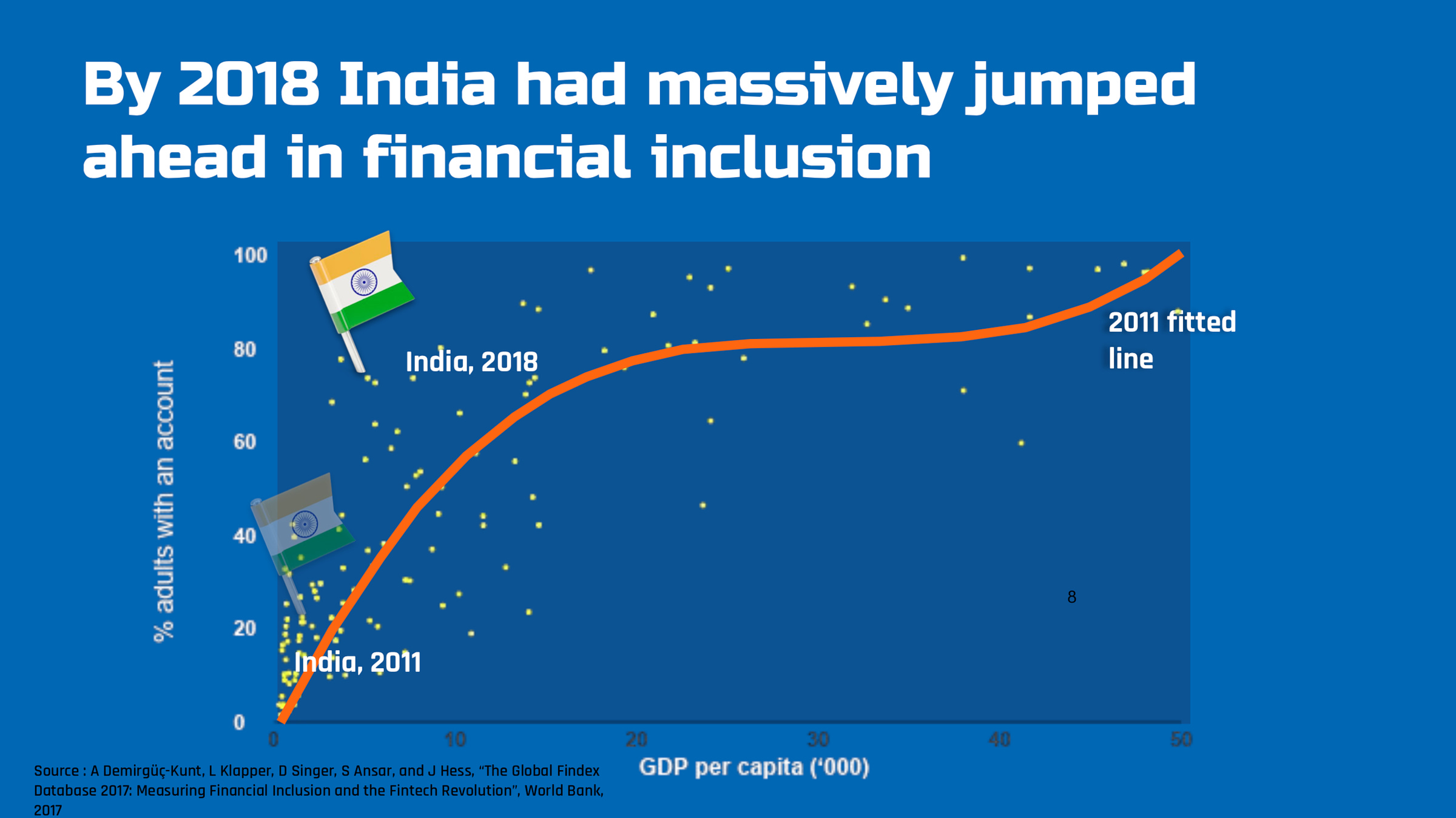

Remember the dire statistic we mentioned earlier – that only 17% of Indian adults had a bank account in 2009? By 2018, that figure had skyrocketed to over 80%. Aadhaar was the key that unlocked this financial revolution.

Through a process known as e-KYC (electronic Know Your Customer), Aadhaar dramatically simplified the process of opening a bank account. What once required a stack of documents and several days could now be done with a fingerprint and a few minutes. The World Bank estimates that this technological innovation - duly enabled by concomitant regulatory allowances - brought the cost of customer onboarding for Indian banks down from $23 to a mere $0.15.

That’s a 99.3% or 153x decrease in cost…

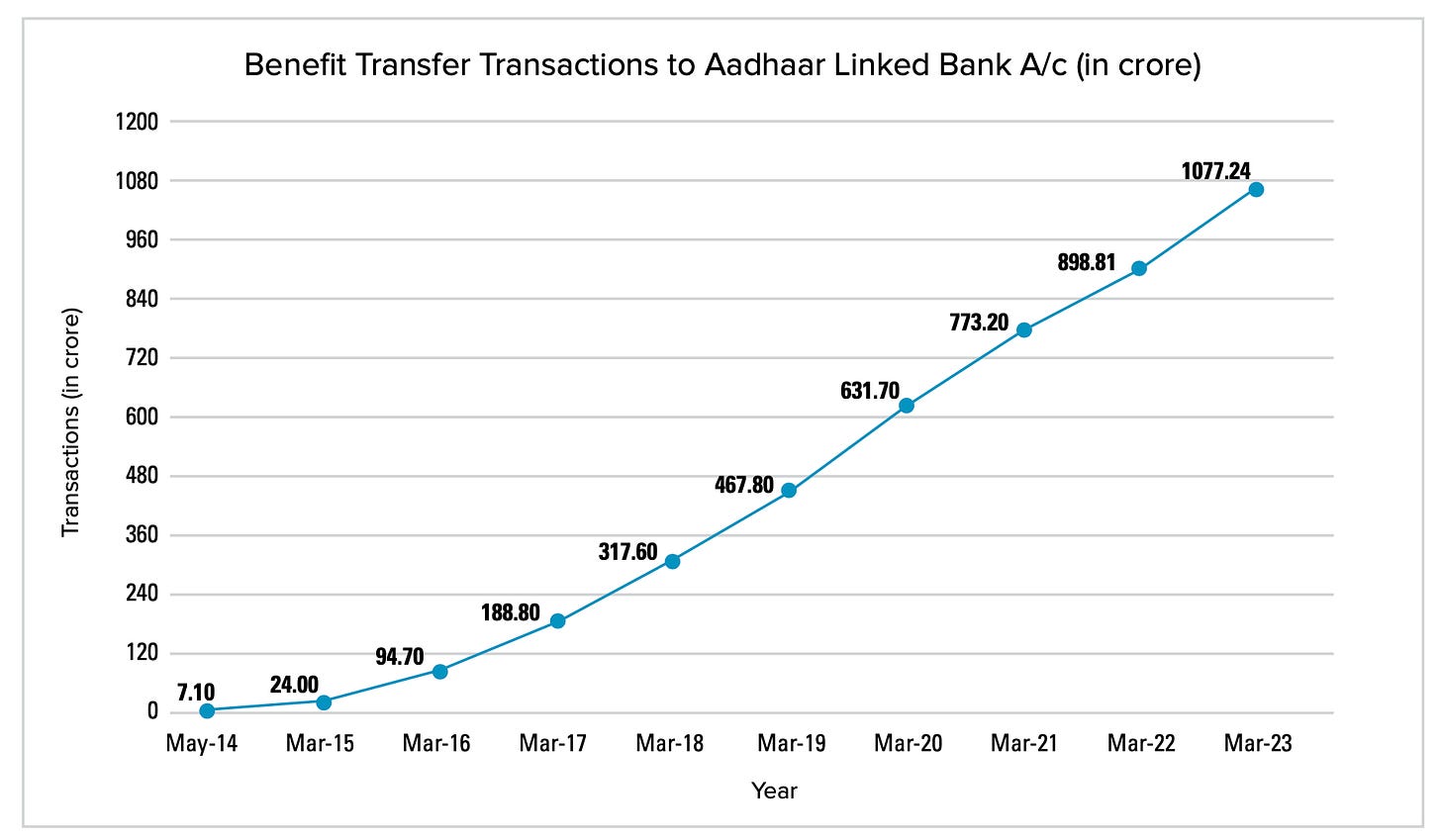

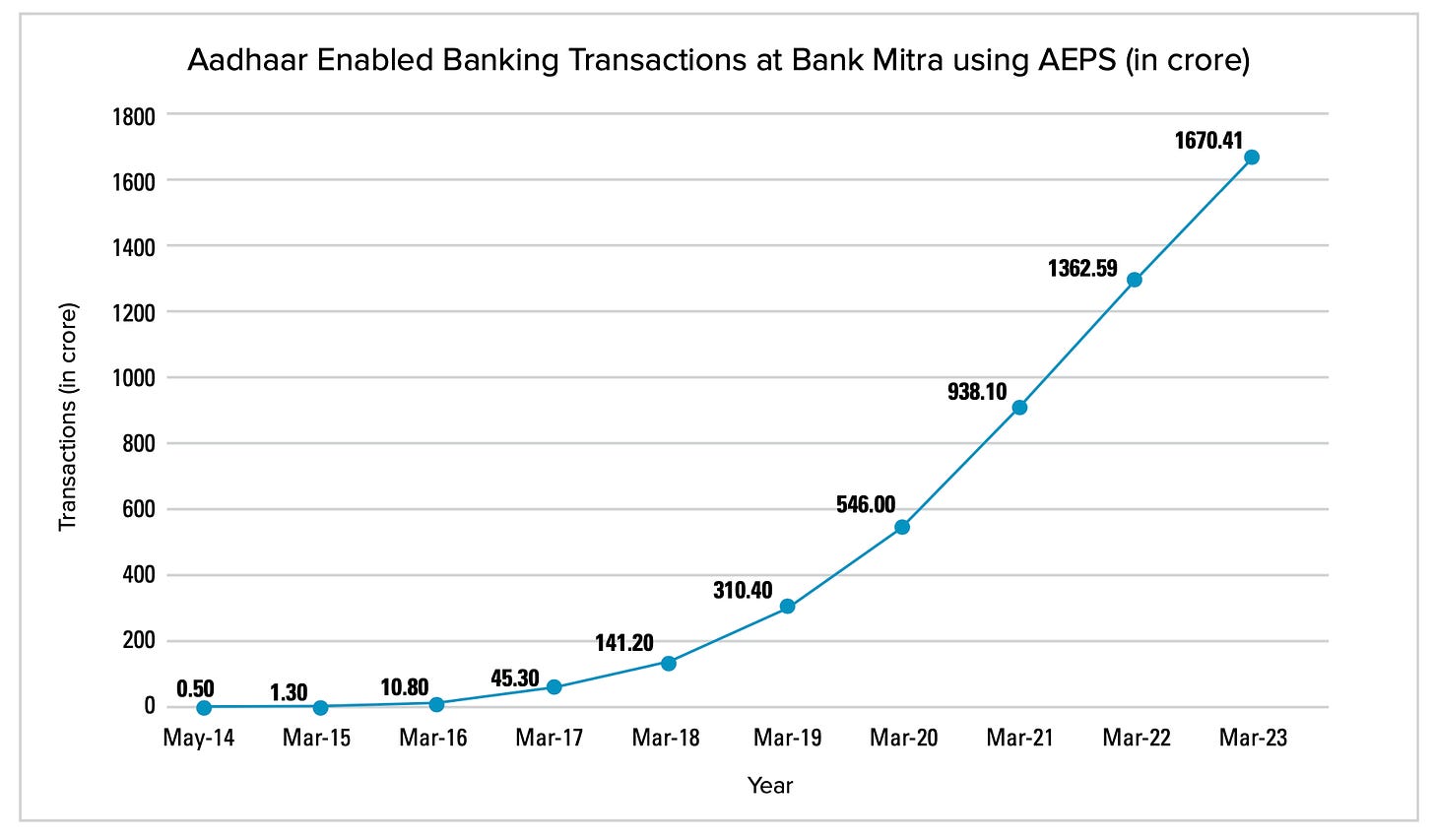

Precisely. But these new bank accounts weren't just for show either. They became the conduits for two transformative initiatives: the Aadhaar-Enabled Payment System (AEPS) and Direct Benefit Transfers (DBT).

AEPS allowed banks to turn every corner shop with a biometric reader into an ATM or payments terminal. In regions where the nearest bank branch might have been an arduous day-long hike away, people could now withdraw cash, deposit savings, check their balance, or transfer money with just their Aadhaar number and a fingerprint. Side note: AEPS was launched by UIDAI in concert with the fledgling National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI). NPCI would go on to launch UPI in 2016, which is now known globally as the gold-standard of real-time payments systems.

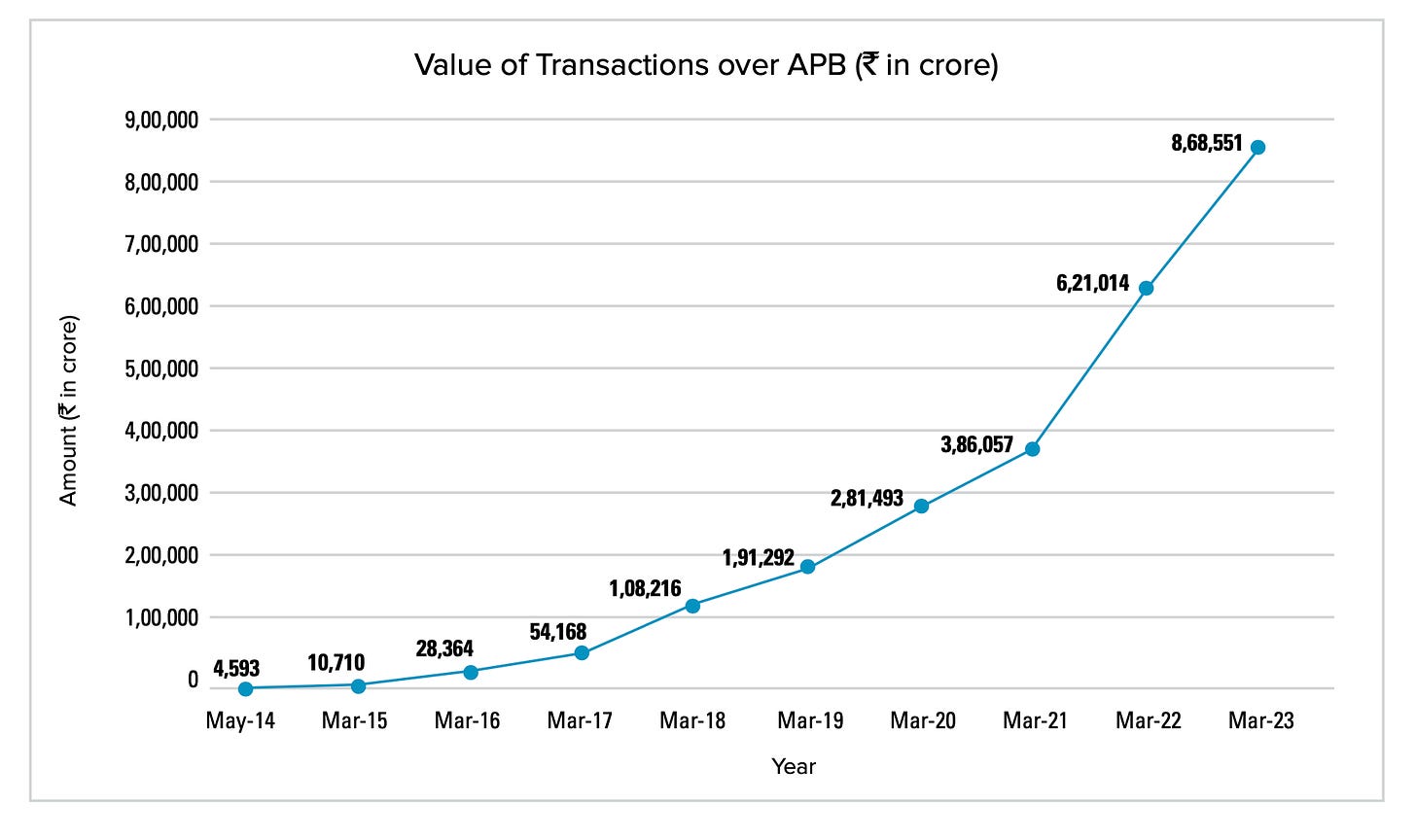

In the year ended March 2023, AEPS processed over 16 billion transactions, moving over 20,000 crores ($2.4 billion) every month. It was a perfect low-value, high-volume payment mechanism for the rural poor to manage their cash and pay their bills.

DBT, on the other hand, revolutionised how government benefits reached the poor. Instead of passing through layers of bureaucracy – each layer skimming its share – money could now be transferred directly into the beneficiaries’ Aadhaar-linked bank accounts via a channel called the Aadhaar Payment Bridge (APB). The impact was immediate and substantial. Just last year, around $83 billion in benefits was transferred directly to hundreds of millions of Indians, eliminating middlemen and reducing leakage.

The resulting savings to the taxpayer have been enormous. To illustrate, let’s look at India’s cooking fuel subsidy scheme. In the absence of extensive piped gas infrastructure, millions of families rely on cylinders of liquified petroleum gas (LPG) to serve as their source of cooking fuel.

India imports this fuel, and its price fluctuates depending on geopolitical factors. To insulate the population from this volatility and to bring down the cost of an essential basic necessity, the government of India offers a cash rebate to subsidise the cost of purchasing LPG cylinders for domestic consumption.

Other consumers of cooking gas - such as restaurants, hotels, offices, and commercial kitchens etc - have to pay the full price. However, many of these commercial consumers used to circumvent the rules by either procuring LPG from the black market or by setting up fake identities they could leverage to claim the subsidy.

With the advent of Direct Benefit Transfers (DBT), the number of ghost and duplicate beneficiaries declined dramatically. The risks and costs of running black market operations also increased, resulting in less demand for black market cooking gas. This study from 2014 calculates the fraud in the pre-DBT LPG subsidy system at 11-14%. Given that India spent $7 billion on LPG subsidies that year, the quantum of public funds that could have been saved in 2014 amounts to almost a billion dollars.

And it doesn’t stop there. Aadhaar-linkage is now widespread in nearly all of the Government’s 490-odd welfare schemes. This ensures that duplicate and bogus beneficiaries are weeded out, and that the transfer payments and benefits are accessed by the intended beneficiary without any pilferage along the way.

The government claims that last year, the DBT scheme resulted in savings of 63,000 crores or almost $8 billion. Cumulatively, the savings arising from DBT come in at 350,000 crores or $42 billion.

OK that’s a lot of money that was previously just being… stolen or wasted?

Exactly.

But Aadhaar's impact extends far beyond welfare distribution. It has become the foundation of much of India's digital public infrastructure, spawning a host of innovative services including:

DigiLocker, the platform for digital issuance and verification of documents (think driver’s licenses, tax cards, vehicle registrations) eliminating the need for physical documents.

eSign, which allows users to digitally sign documents, revolutionising everything from loan applications to government filings.

The financial inclusion catalysed by Aadhaar also laid the groundwork for the success of India’s much-vaunted UPI real-time payment system, and the rapidly ascending Account Aggregator framework for financial data sharing.

All things taken together, the picture has improved greatly not just for the government, but also the average Indian. They’ve gained convenience, savings, and access to the formal economy.

Which helps to explain why this graph has been trending downwards and is currently hovering between 4-12% of the population living in poverty, depending on who you ask and how you define poverty.

Of course, it would be reductivist to attribute all of this development solely to Aadhaar - there were numerous other policy interventions, economic forces, and social initiatives that helped bring about the massive reduction in multi-dimensional poverty - but it’s no exaggeration that Aadhaar played a central role in dragging the country out of the past and creating the foundation for the future.

Yet for all its success, Aadhaar stood on the brink of failure before it even began. All of these innovations, all of this development - may have simply never occurred due to one big problem.

The culprit? Biometric deduplication.

In English, please.

OK, let’s take a step back.

Aadhaar’s promise could only be fulfilled if one key attribute was upheld: uniqueness. Each Aadhaar number had to correspond to one, and only one, individual. No duplicates, ghosts, or synthetic identities could be allowed into the system.

The solution to this challenge lay in biometrics - the biological characteristics of fingerprints and iris scans that are unique to each individual. By capturing and comparing these traits, UIDAI could, in theory, ensure the uniqueness of each identity in its vast database.

This process of comparing biometric scans in order to filter out duplicates is known as biometric deduplication (or dedupe for short).

Got it. So what was the problem with it?

The sheer scale.

Every time a new person enrols in Aadhaar, their biometric data needs to be compared with every single other record in the database to ensure that they're not already registered.

Recall that the Aadhaar database was supposed to contain the data of over a billion people. Now consider that for much of the early 2010s, UIDAI was enrolling close to a million people every day.

For each of these people, the system had to do the following comparisons:

Compare demographic information (name, address, birthday, gender, mobile number, email address)

Compare biometrics (ten fingerprints, two irises, one photograph)

That’s a total of 19 things that need to be checked per person. Against every single other entry in the database…

I see where you’re going with this…

For each new user being enrolled into a billion-strong database, the biometric deduplication steps that need to be conducted are 19 times one billion. So nineteen billion.

Now if you include the other one million people who are enrolling on the same day, the number of daily computations you need to conduct grows to nineteen quadrillion.

Here, let me write that out for you.

19,000,000,000,000,000.

To put that in perspective, that’s about six hundred times greater than the number of all trees on Earth.

But it gets more complex. Biometric matching isn't a simple yes/no comparison. It's probabilistic, requiring sophisticated algorithms to determine if two biometric samples are likely to be from the same person. These algorithms are computationally intensive, making each comparison a non-trivial task.

To appreciate the audacity of what India was attempting, consider this: In 2009, the largest existing biometric database in the world was the United States VISIT program, used for border control and immigration. It contained about 100 million records. Aadhaar was aiming to be more than 12 times larger.

The U.S. system, built and maintained by some of the world's leading technology companies, relied on specialised high-performance computers and proprietary software that cost billions of dollars to set up and operate. When the architects of this system looked at India's plans for Aadhaar, their verdict was cutting: theoretically possible, but economically unfeasible.

Srikanth Nadhamuni, UIDAI’s Head of Technology and the panicked caller from the start of our story, was told that UIDAI would require a data centre the size of several cricket fields to house the computers needed to store and process that volume of data. Pramod Varma, the Chief Architect of UIDAI, recalls being issued an equally jarring caution:

‘I remember being told that we would need a million computers worth a million dollars each for the de-duplication process.’

Nilekani, Nandan; Shah, Viral. Rebooting India (pp. 66-67). Random House Publishers India Pvt. Ltd.. Kindle Edition.

That’s one trillion dollars of capex!

Clearly, something was not adding up. The biometric deduplication on its own was shaping up to be an impossible task, without even factoring compute requirements for other things like storage and general authentication.

What do you mean by authentication?

To enable people to leverage their identities, Aadhaar offers two modes of digital identity authentication: e-auth and e-KYC.

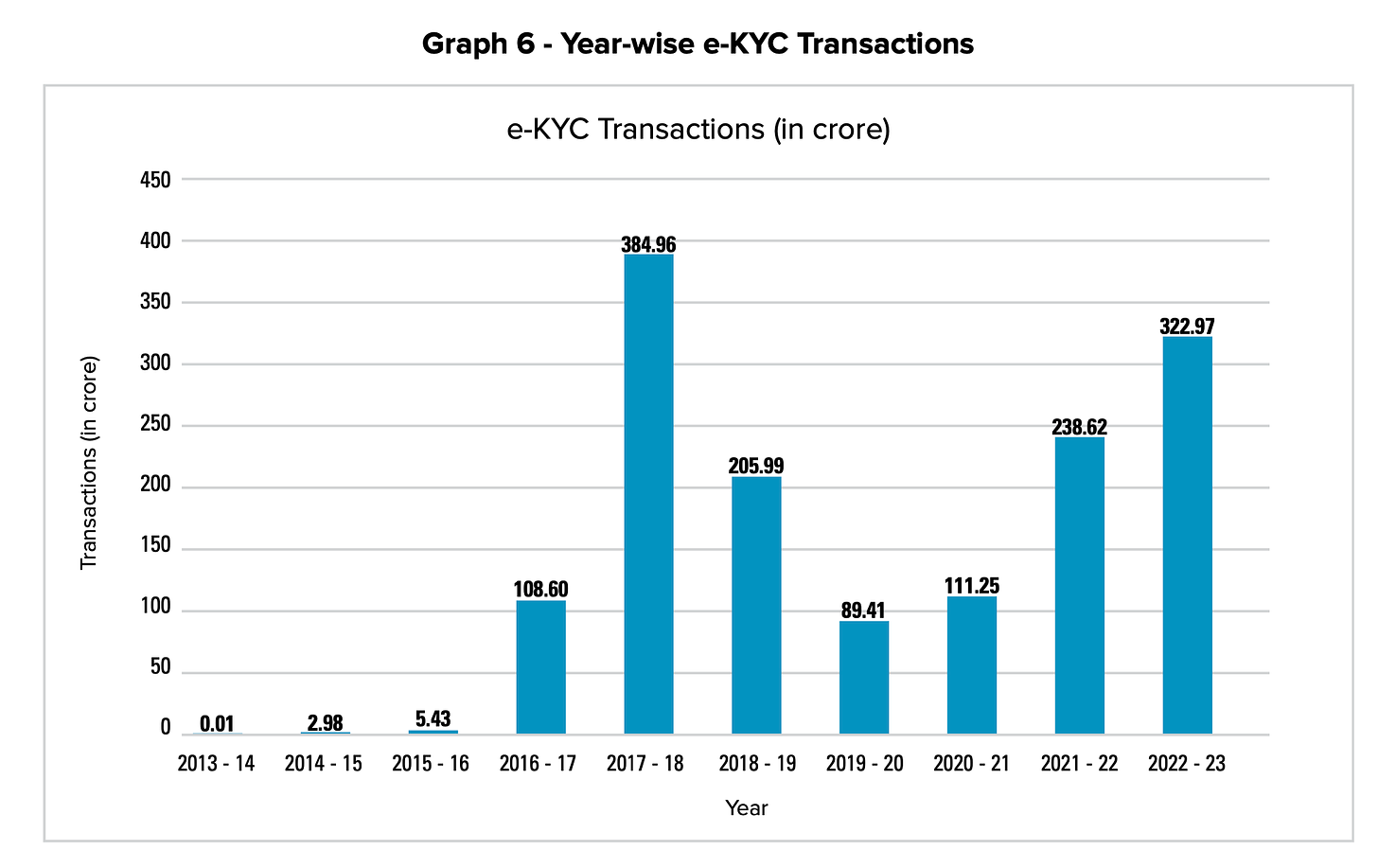

We already spoke about e-KYC earlier on - it was the process used by banks to rapidly and cheaply collect and verify demographic information about a customer. It works by taking a user’s Aadhaar number and biometrics and sending them to UIDAI. If the number and scans match with an existing record, the system sends back the photograph, name, age, gender, and address of the user.

This allows the bank or telecom company (these are the only two kinds of entities legally allowed to use this product) to ensure that the customer standing in front of them is who he says he is.

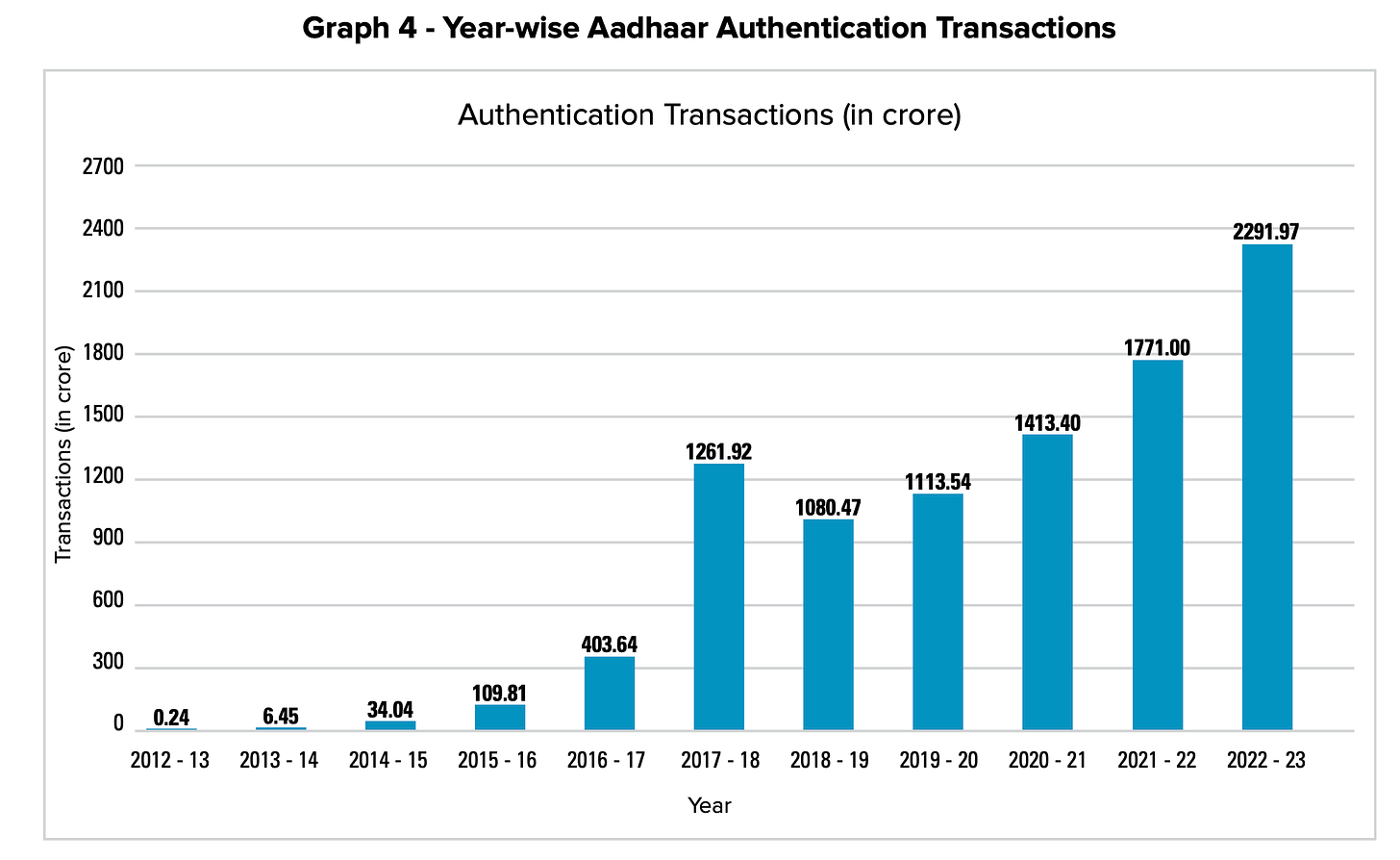

In contrast to e-KYC, e-auth does not always have to involve biometrics. To use e-auth, a company or government department must send a user’s Aadhaar number and demographic information (name, date of birth, address, or gender) to the CIDR. User consent must also be collected, either by OTP or via biometrics.

In response, the CIDR merely spits out a ‘YES’ or ‘NO’ response. This is a simple but powerful modality that forms the basis for lots of online services such as eSign and DigiLocker.

Despite its significant scale (23 billion transactions last year), e-auth is still an underrated and underutilised product. Although the Supreme Court has restricted e-auth use to a few regulated entities and government departments, the private sector use cases are very alluring. Fundamentally, e-auth can be used to ascertain selective information about a user without requiring their whole identity - think of a website for women only or people of a certain age or from a certain town. This is an surprisingly flexible and potent product capability, and it can be leveraged safely without revealing anyone’s real Aadhaar number; in 2018, UIDAI introduced a feature called virtual IDs which allow authentication using a freshly generated 16-digit number, kind of like a temporary credit card number.

The other obvious and prescient benefit of e-auth is proof-of-personhood in the age of AI. It is rapidly becoming impossible to distinguish between bots and humans online, but Aadhaar’s biometric moorings ensure that all authenticated users must be real human beings. This represents an increasingly important capability, one which entities like Sam Altman’s WorldCoin are spending billions to acquire.

You’re digressing, get back to the point.

Sorry. The point is that e-KYC and e-auth each have tens of billions of transactions each year. Back in 2009, designing a system of that scale was far from trivial. When you add in the completely outlandish requirements of the biometric dedupe (quadrillions of computations per day!!), you begin to understand the colossal challenge that faced the UIDAI technology team.

And as if all of that wasn’t already enough, there were other factors to consider. In 2006, the Labour government in the United Kingdom passed a bill to introduce a National ID card. Along with mooted savings of a billion pounds per year, the main rationale was to expand access to services, eliminate paper-based friction, and stamp out identity and benefits fraud.

However, the project turned out to be a financial and political disaster. By 2010, the government had spent 40m pounds on IT consultants and still had nothing to show for it. In addition to the vehement opposition from civil society concerned about a curtailment of personal liberties, the project also came under fiscal scrutiny from the Conservative opposition who argued that the project would cost 20 billion pounds (the Tories eventually scrapped it as soon as they came into power in 2011).

All of these developments in the UK served to fan the flames of opposition to Aadhaar in India. The Indian population was used to state profligacy, operational incompetence, and wanton corruption. Aadhaar seemed like it would have the makings of all three.

After all, not only were renowned global experts saying that it was impossible, the wealthy UK government had spectacularly failed in their attempt to produce a far smaller system. Surely the Indian taxpayers funds that would likely be swallowed in this futile attempt would be much better served elsewhere.

It was the perfect storm of cynicism, opposition, and doubt.

And into that storm stepped Pramod Varma.

Who?

Dr. Pramod Varma was the Chief Architect of Aadhaar, and the man upon whose shoulders the Atlantean technical challenges of Aadhaar were hoisted.

If you didn’t know him, nothing about Pramod’s appearance or mannerisms would give away the prized contribution he has made to India’s technological revolution. With his slim build, thin spectacles, and neat crop of thick black hair, his appearance is not dissimilar to a kindly professor. But behind that gentle demeanour lies the mind of a wizard, one who would conjure up the magic required to deliver not just Aadhaar, but also UPI, ONDC, Account Aggregators, and several other building blocks of modern India.

Pramod's intriguing story began in the balmy town of Thrissur, Kerala. Just like any regular kid from Thrissur, Pramod attended a Malayalam-language school and spent most of his time playing with the neighbourhood kids. In many ways, he had a very normal, nondescript upbringing.

Except for one big difference: he came from the nobility. More specifically, Pramod’s family were descendants of Raja Ravi Varma, one of India’s most important artists and a member of the royal family of Travancore. Side note: one of Raja Ravi Varma’s famous beliefs was that ‘art should not be limited only to palaces’. To further that end, he set up a lithographic press in 1894; this would result in a proliferation of religious iconography that allowed millions of Indians to bring a piece of God into their homes for the first time. You could say that democratising technologies are in the Varma genes :)

But despite this rich heritage, Pramod grew up without a hint of regal trappings. The winds of change that swept through post-independence India had long since blown away any remnants of royal privilege. Kerala, in particular, was one of the first states to elect a communist government; so although Pramod’s parents grew up in a palace, they faced a harsh transition to civilian life. By the time Pramod grew up, nobody looked twice at him, he was "a commoner through and through."

In a twist of fate, Pramod stumbled into the domain of computing almost by accident. His entry into the tech world came not through careful planning or familial pressure, but through a chance encounter with a newspaper advertisement.

One day, while flipping through the pages of a local paper, Varma's eyes fell upon an ad for Hyderabad Central University. They were offering a master's degree in applied mathematics. Pramod, who had studied maths in college but really had no idea about the options for higher technical education, was intrigued. On a whim, he applied.

Soon, Pramod found himself in Hyderabad, a fish out of water. He couldn't speak Telugu, Hindi, or Urdu, so he had to rely heavily upon his not-so-good English and the college’s Malayali population to help him get around. Armed with nothing but determination and a knack for numbers, Pramod not only survived but thrived. He fell in love with computing and secured a PhD in database systems.

After graduation, serendipity would take Pramod by the hand once again. He found himself working as an early employee at a young IT firm called Infosys. He recalls with pride how he was the first employee at the company to get access to the Internet in 1994.

He used this privilege to build all manner of apps on Mosaic, the world’s first web browser and Marc Andreessen’s precursor to Netscape. Soon, Pramod’s exploits piqued the interest of Infosys co-founder Nandan Nilekani, who saw a kindred spirit in the inventive programmer.

Together, they worked on Project Viking, Nandan’s early vision for Internet banking (complete with dynamic data and transaction processing capabilities!). Although this particular undertaking was a little too far ahead of its day, it marked the first time that Nandan and Pramod teamed up; a pairing that would have immense impact on India in the following decades.

Nonetheless, there would be a 15-year interlude before they combined their talents again. After a period working at Infosys, Pramod found greener pastures in the US. He spent several years there working his way up to the position of CTO of a global supply chain company.

But by 2003, he was ready to come home. He might well have remained in the States as one of several Indians to ‘make it’ in America, but he felt a beckoning back to his roots. That decision would soon bear fruit, thanks to another timely newspaper discovery (I know, clearly the man is blessed by the newspaper gods).

On a lazy summer Sunday in 2009, just a couple of weeks after he had finished reading ‘Reimagining India’ - Nandan’s inspirational clarion cry to build a modern nation - Pramod spotted an article discussing the monumental challenge facing Nandan as the Chairman of UIDAI. So he decided to reach out to his old boss and see if he could contribute to the great nation-building exercise afoot in Delhi.

The rest, as they say, is history.

History? What, no! We don’t know or want to read any more history, just tell us how they solved the dedupe problem!

When confronted with the experts’ withering assessment of the project’s chances of success, Pramod and the UIDAI technology leadership team (including Pramod, Srikanth Nadhamuni, Vivek Raghavan, and Raj Mashruwala) decided to approach the problem from first principles.

They spent time immersing themselves in the fundamental functions and requirements of the system that they had to design. What exactly constituted a biometric scan? How was this data represented to a computer? What was the nature of the deduplication algorithm? To answer these questions, they spent time with many of the scientists and programmers who pioneered these technologies.

Simultaneously, they also spent time introspecting on their own timelines, bottlenecks, and project requirements. What was the data they needed to capture? Were there any speed or customer service benchmarks they had to maintain?

After carefully considering all these details, they realised that the biometric deduplication challenge belonged to a class of computer science problems known as Embarrassingly Parallel Problems. In other words, they were problems that could be broken up into many small pieces, each of which could be solved independently of the others.

To illustrate, imagine a table of 100 snooker balls each having their own unique number. When the 101st snooker ball is introduced, the system needs to check whether the number it bears is written on one of the 100 balls already on the table. If so, it must reject the new ball, or otherwise add it to the table. This is basically the essence of the deduplication problem.

One way to tackle the problem is to get a single extremely fast ball-counter to quickly sort through all the balls. Another way is to divide the 100 balls into smaller groups of say 10 and get 10 average-speed ball-counters to sift through one group each. Chances are the slower ball-counters will complete their task in a time that is comparable to the fast ball-counter.

The real-world parallel to the fast ball-counter was the high-performance computer favoured by the US VISIT system and all the other major biometric databases of the era. These machines boasted Application Specific Integrated Circuits (ASICs) that were built for one thing and one thing only - to quickly compare biometrics. The upside of these systems was that they were incredibly fast and efficient. The downside was that they were very expensive and difficult to operate - they were only sold by select vendors who locked you into long term contracts. It would be extremely difficult to ever swap out this technology or change your vendor. Once you were in, you were in for life.

In contrast, the parallel to the 10 slow ball-counters was X86 blade servers. Think of your run-of-the-mill computers powered by Intel and AMD chips that you can find anywhere and everywhere. Now imagine stripping away all of the fancy stuff from them that you don’t need and keeping only the essential processors you need to get your job done. That is an X86 blade server.

Literally the whole world runs on these things. They are a pure commodity and everybody knows how to build and maintain computer systems with them. The downside to these computers was that they were slow and unspecialised, meaning they had poor performance. The upside was that they were cheap, well understood, and had one huge ace in the hole: Moore’s Law.

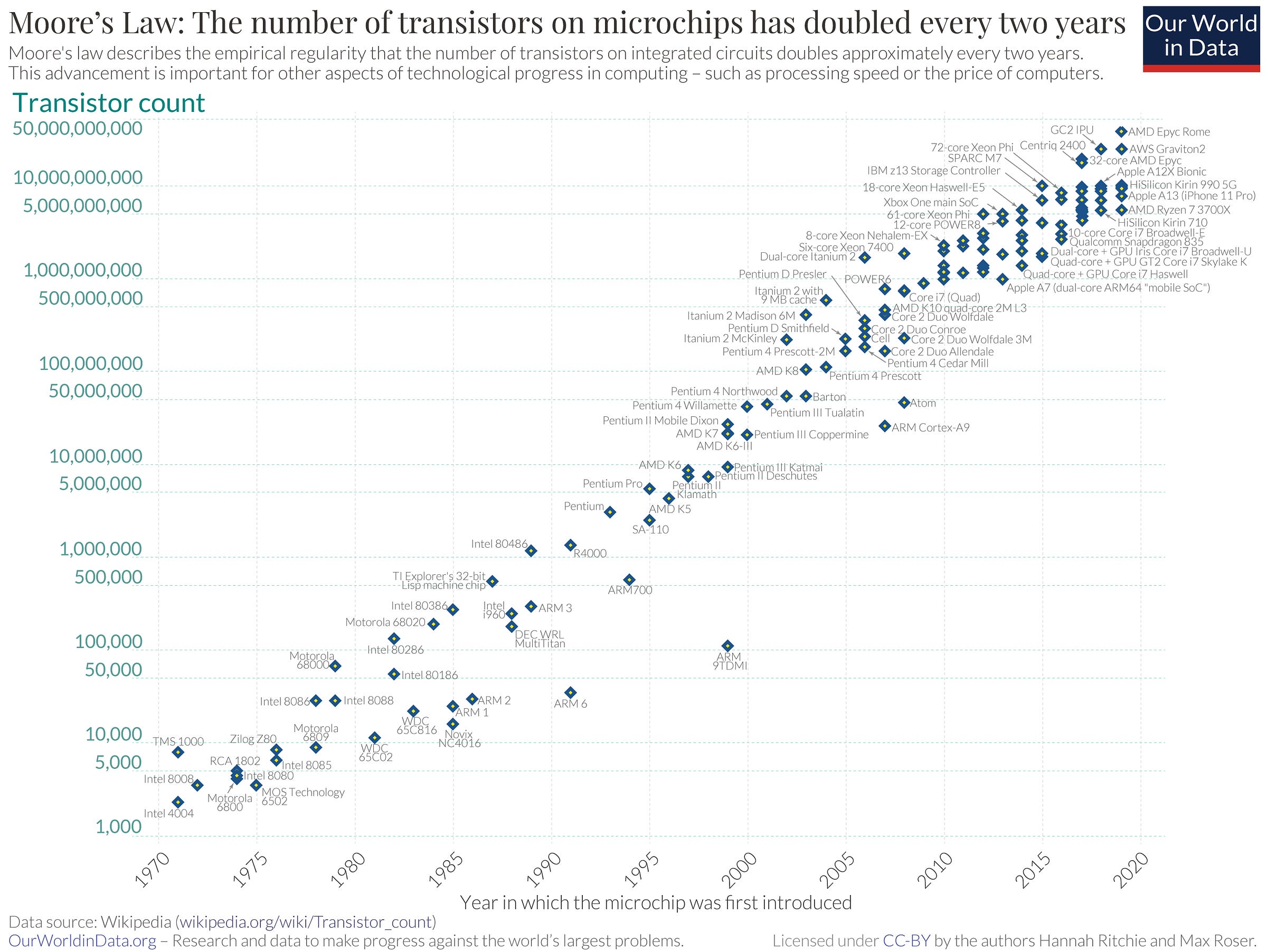

For the uninitiated, Moore’s Law refers to a prediction made by Gordon Moore, one of the founders of Intel and a father of modern computing. He said that owing to the rapid advancement in the scale and sophistication of chip making, the number of transistors on a chip would double every two years (transistors are what allow a computer to do logical and arithmetic operations).

In other words, computers will get faster, smaller, cheaper, and more energy efficient every two years. This is the reason why your smart toaster currently possesses more computing power than man’s first moon mission, and why there are more transistors in a single one of your new Airpod Pros than there were in your entire Macbook 10.

So taking all this into account, the UIDAI tech team and product team (ably led by the extremely talented and influential Sanjay Jain) realised two things:

Firstly, enrolment throughput was the bottleneck, not latency. In plain English, it was not acceptable to have a slow signup flow at the enrolment kiosk. Since there would be hundreds of people lining up to get an Aadhaar at the same time, you needed the queue to move fast. So the signup and biometric data collection had to happen as snappily as possible. On the other hand, it was acceptable to actually issue someone’s Aadhaar number a few days after they signed up. No harm was done if someone signed up on Monday and only got actually enrolled on Friday - in fact, people even expected that pace. This was a key insight, because it meant that the biometric deduplication could afford to be slow.

Secondly, the team realised that the biometric deduplication challenge would not be so scary in the early days of Aadhaar. In the first several months of the operation, the database would have relatively few records. Even if the enrolment drive exceeded all its targets (which it did), there were still four or five years after launch before the database approached a billion records. In other words, Moore’s Law had time to kick in before the deduplication entered its hardest phase.

This was enough for our protagonists to gain clarity about the hardware choice. They decided that they would eschew the fancy American supercomputers in favour of assembling a large array of basic X86 blade servers working in parallel. Yes, the homebrewed parallel system would be slower, but the slowness was tolerable. Plus, it would get faster over time. Most crucially, it did not come with any vendor lock in, so the UIDAI team had full freedom to upgrade, change, or remove parts of the system as they pleased.

Oh, OK. Seems like a straightforward decision, then?

It might seem like a simple and straightforward decision in hindsight, but you have to understand that the team was flying blind at the time. They had no idea if Moore’s Law would continue, and if so, at what rate. It’s not as if Moore’s Law is a fundamental law of physics that remains constant, it’s just an estimation of the rate of improvement in semiconductor manufacturing technology.

Furthermore, nobody had ever attempted a solution like this for a biometric database of this size. In fact, the era of ‘big data’ and massive cloud computing hadn’t kicked off yet globally. Back in 2009, Amazon hadn’t even migrated its own servers to AWS (Amazon Web Services - a cloud computing platform that basically half the world runs on).

Google and Facebook were two of the only companies who had achieved global scale building on the Internet, and they were really writing the rulebook as they went along. Incidentally, Pramod and his colleagues spent time in San Francisco with the engineering teams of these companies to validate his hypothesis for the UIDAI system architecture. The Valley CTOs agreed with his reasoning, but even they weren’t comfortable predicting whether the system would work or how much hardware would be needed.

In the end, the UIDAI team decided that the experts’ suggestions of a cricket pitch-sized data centre were overblown. They decided to be safe and go with a 20,000 square-foot data centre instead.

So… it wasn’t a straightforward decision.

No, not at all - there were several unknown variables and lots of pressure from all sides. Foremost among them were the government procurement controllers - these were the people responsible for managing the project finances.

They were answerable to Parliament and to the taxpayers, and they did not want their careers jeopardised because some private-sector software engineer decided to play cowboy.

They had a simple question: “if the experts said to buy 10 fast computers costing 100 bucks total, why are you making us buy 1000 slow computers costing 200 bucks total?” To any rational observer, it seemed like they had a perfectly fair point. Pramod was risking the entire success of the project, and all those crores of taxpayer money, to go against the recommendation of the people who basically invented biometric deduplication.

Most normal people would probably feel extreme anxiety and lose their nerve when faced with this sort of pressure. But not Pramod; “I’m a software architect”, he says. “This is what I do. If your decision is based on sound logic that you can confidently explain in the face of questioning, then what’s the issue?”.

And so that settled the case of the hardware requirements.

Well, what about the software, then?

Foreshadowing the principles that he would embody for the rest of his career, Pramod took the decision to place his trust in open-source software and API-based architectures.

Can you explain it so that I don’t need to get a computer science degree to understand?

As far as possible, Pramod took the call to build the Aadhaar system using open-source software. That means software that is readily available in the public domain - anybody can read it, study it, and build on top of it.

Because this kind of software is so widely available, the talent pool that has expertise in it is large. So it is easy to get engineers who can maintain and extend it. For this reason, several components of the UIDAI system are built on top of open-source frameworks and technologies that have wide adoption and support.

The one key software component that still relied on closed-source, proprietary software was the biometric deduplication algorithm. In this domain, the specialised offerings built up by a few companies were just far and away more efficient than the commoditised alternatives.

But even so, Pramod didn’t just cave in to the software vendors, he made them sing for their supper. Because UIDAI was going to be the world’s largest biometric database project by a factor of 10, they had incredible negotiating strength.

UIDAI used this leverage to bend the software vendors to their will. The three vendors who won the government’s tender (an American firm, a French firm, and a Japanese firm) were all told that they would have to compete with each other for business. Nothing would be guaranteed to them, and none of their solutions would be getting a free integration with the main UIDAI database.

Instead, they had to communicate with a piece of custom middleware written and maintained by the UIDAI team.

You’re going to need to simplify this again, chief.

OK, picture the middleware as a robot drill sergeant working with three recruits: the Japanese, the French, and the American (the vendors).

The drill sergeant defines a set of APIs - or procedures - that each recruit needs to learn. The requirements of each API are standardised for all three recruits, and the exact form in which they receive and respond to instructions is painstakingly documented. They must only communicate and behave according to these clearly-defined procedures.

One of these APIs is a heartbeat API, which requires the recruit to just shout out a greeting to the sergeant, indicating they are awake. Another is the push-up API, which requires the recruit to do a certain number of pushups. In this procedure, the sergeant closely monitors the speed and form of the recruit’s pushups.

Now, the deal that UIDAI had with the three vendors was conditional on their adherence and performance on these APIs. The heartbeat API implemented in the middleware would give UIDAI a continuous way to monitor the system health of the vendors’ systems - were some of them frequently going down or were they all reliable?

The pushups API is analogous to the biometric deduplication task. The UIDAI middleware would push a packet of user enrolment data to the vendor and ask it to respond by confirming or denying whether the user was already in the database. The speed of the vendor’s response, along with the accuracy, would be taken into consideration. To test the accuracy, the UIDAI team would often send fake or duplicate test packets to the vendors to see how they fared. In this way, they would continuously assess the reliability and performance of each of the three vendors.

Basis this data, the highest ranking vendor would be given the bulk of the biometric deduplications to perform - and since the vendors only got paid per deduplication request that they performed, this kept them in constant competition to improve and deliver.

If all of this sounds a bit like a Full Metal Jacket, it may be because it actually was. Pramod recalls a meeting in which a vendor flew down to demonstrate their algorithm. The UIDAI team heard the pitch and told the engineer - ‘OK it seems to be working fine in this demo, but what if our hardware starts failing?’. The engineer confidently replied that the algorithm would work fine. Smiling widely, a UIDAI official instructed him to go to the wall and slowly unplug half of the servers that were running the algorithm. The engineer’s face turned white as a sheet. The vendors had no idea what hit them - they had never been tested so rigorously!

Woah, that actually sounds like an intense and innovative way of doing things!

You can say that again.

This was a revolutionary way of doing things that would have made Silicon Valley gurus proud, so it was a complete shock to the government critics and solution providers who expected the engagement to be an easy ride.

What were the results in the end? Did these decisions pay off?

As you can probably guess from the direction of this essay, the team’s decisions paid off spectacularly with regards to hardware.

Although the initial outlay on commodity computers was larger than the initial bill for supercomputers would have been, the long term costs played into UIDAI’s hands beautifully. They were able to keep maintenance and operation costs very low, and they profited hugely when Moore’s law kicked in.

Because their system architecture allowed them to use a heterogenous mix of commodity computers in the data centre, they could easily swap out their old machines whenever Intel or AMD released a more powerful chip. This allowed the processing power of their data center to stay ahead of the ever-increasing computational workload required to deduplicate the growing identity repository.

In the end, even the 20,000 square feet carved out for the data centre ended up being too generous. The final size of the UIDAI data centre is only 4000 square feet! The rest of the space got converted into offices (some lucky folks probably got cabins 3x the original size because of all the excess space!).

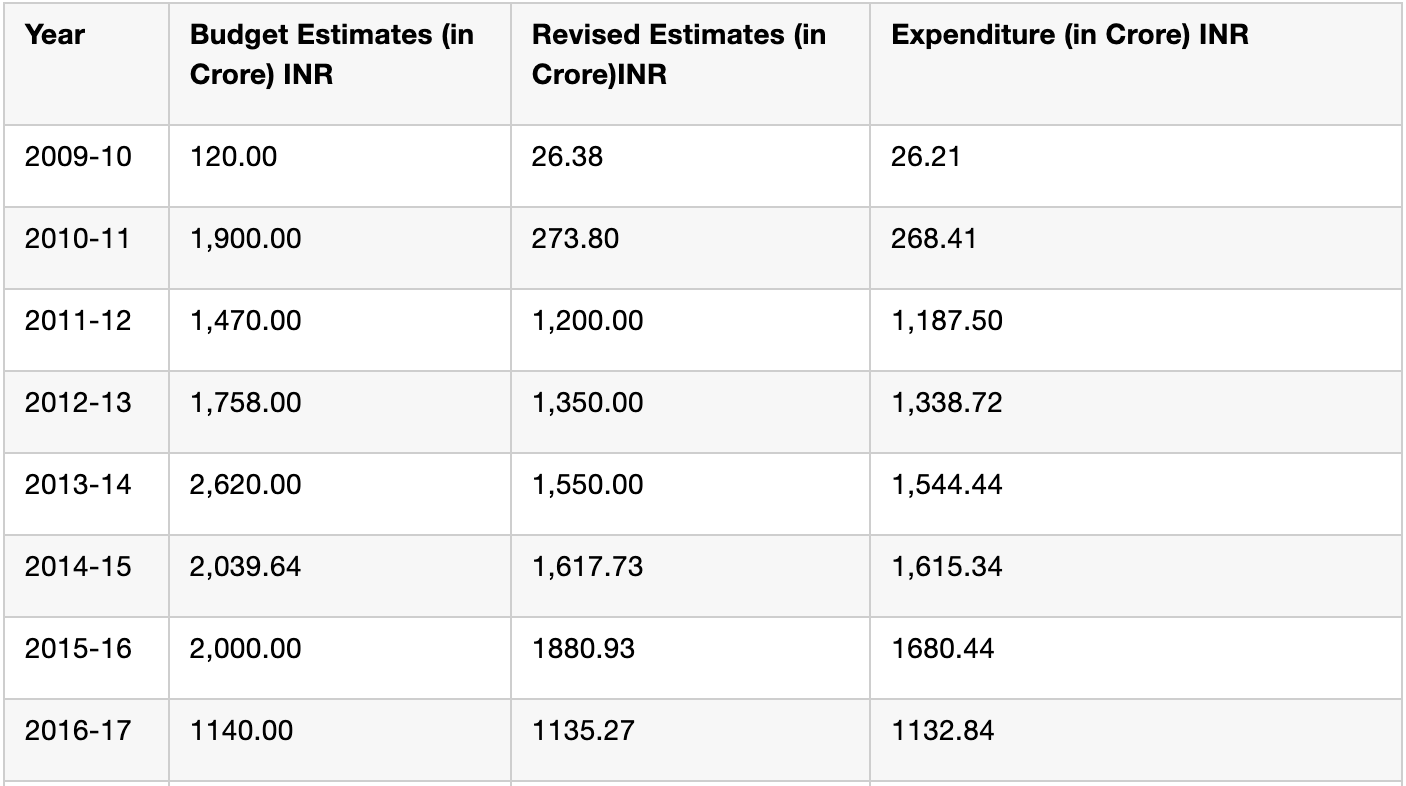

As you can see from the annual UIDAI budgets, the project undershot its budget in pretty much every single year of its existence, saving crores of rupees in the process. The final expenses seem almost unbelievably frugal for a project of this magnitude that was once projected to incur capex costs of a trillion dollars!

And as for the software architecture decisions, they paid off handsomely as well. By using APIs as the means of communicating with the vendor software, UIDAI was able to avoid getting too dependant or closely integrated with any one vendor. When one of the vendors had to be replaced in 2013 due to performance issues, the changeover was seamless.

Pramod is particularly proud of this fact, emphasising that the massive operations underway in 2013 were not disrupted in the slightest by a procedure as major as swapping out a key vendor of a mission-critical algorithm. He giggles as he likens it to swapping out the engine of a 747 mid-flight. As it turns out, Aadhaar Airways had nary a hiccup with their mid-air upgrade, either back in 2013 or in subsequent years when they would deploy new features.

Along with providing failure-resistance and smooth upgradability, the software design choices also offered the benefit of very low costs. The uniquely competitive square-off between the vendors was a key part of this design.

As a result of competition and scale, it was estimated that UIDAI’s cost per de-duplication was the lowest in the world by a factor of three. Srikanth Nadhamuni explains the numbers to us. ‘The worldwide benchmark for a single de-duplication was on the order of Rs 20. We managed to carry out de-duplications at a cost of Rs 2.75 per query.’

Nilekani, Nandan; Shah, Viral. Rebooting India (p. 71). Random House Publishers India Pvt. Ltd.. Kindle Edition.

It’s no wonder that so many global commentators have expressed their admiration for the way India pulled off Aadhaar!

Wow, you’re really selling the success story here. But what about the controversies and scandals?

In my opinion, there are many legitimate criticisms of Aadhaar.

One of the legitimate criticisms is its legal status. When the program was rolled out, a Bill governing its scope had been prepared, but had not been promulgated. This is attributable to political instability - the opposition party who resisted Aadhaar and the ruling party who wished to implement it both flipped their positions on Aadhaar when their political fortunes reversed. Until one party took a clear majority in Parliament, the issue of Aadhaar’s legal status took a backseat.

Nonetheless, the first legislation circumscribing the application of this technology finally came in the form of a highly controversial Money Bill in 2015. There is no doubt that a proper parliamentary process should have occurred, and that mandating Aadhaar upon the population should not have been allowed without safeguards and common sense.

While the Supreme Court did eventually pronounce a much-needed verdict on privacy and the right not to be enrolled against one’s will, their judgement also curtailed the scope for the private sector to fully utilise the amazing potential of Aadhaar to deliver services.

Moreover, the existence of a data protection law may have helped avert the several data leaks which have taken place involving Aadhaar data. It must be noted that these leaks do not amount to leaks from the UIDAI CIDR but instead reflect the poor information security practices of many other government departments who have leaked their own data which happened to also contain the Aadhaar numbers of users.

It’s worth pointing out here that a user’s Aadhaar number is not akin to a secret password - it is very difficult to harm someone just by possessing their Aadhaar number. But still, everyone has a right to privacy, although I fear that the window to build frameworks and laws protecting privacy was 20 years ago. The modern Internet makes a mockery of privacy, and it seems like the public is becoming increasingly desensitised, as the completely muted reaction to this alleged data leak of 400 million Indians’ names, addresses, and mobile numbers seems to show.

Hopefully the passing of the Digital Personal Data Protection Act and the creation of the new Data Protection Authority of India can help in this regard. Better late than never.

Are there any criticisms you disagree with?

There are three that stand out to me: exclusion, performance, and surveillance.

Many critics claim that Aadhaar has actually excluded many people from the system. They point to instances of individuals being deprived rations because they didn’t get issued Aadhaar cards or because their biometric authentication failed. They are correct - instances like this did take place.

Indeed, whenever a new technology is implemented, there is resistance, oversight, and friction. This study highlights some of the ways in which the introduction of Aadhaar failed or was gamed on-ground. Critically, teething problems in a system like this can probably mean the difference between starvation and survival for some of the most vulnerable people.

But I would challenge the champions of the exclusion argument to weigh up the whole picture - what was the alternative to introducing a new system? A third of the nation was undocumented. Only a fraction of the benefits intended for the poor was reaching them. The status quo was unacceptable, and on the balance of things, the utility generated by Aadhaar greatly outweighs the damage. And as time passes and the system matures, it seems like the teething problems get further and further in the rearview mirror.

Moving on to performance, a common charge against Aadhaar is that there are flaws in the database. It is true that there are cases of people with two Aadhaar numbers. It is also true that a lot of elderly folks and manual labourers experience natural changes to their fingers that reduce the accuracy of fingerprint authentication.

This is caused by two problems: the first is the inherently probabilistic nature of the fingerprint matching algorithm. The second is the inconsistent quality of the sensors and processes used during enrolment. The first is an unavoidable problem which will improve as sensors get better and there is more widespread usage of costly iris scanners instead of only fingerprint readers. The second problem was avoidable, but is still only responsible for hundreds of thousands of errors in a database of almost one and a half billion. That is an acceptable rate of error.

It’s also worthwhile to note that the world’s entire supply of biometric readers in 2009 was completely insufficient to meet UIDAI’s demand. The massive requirement for scanners ended up creating a wave of new biometric device manufacturers that literally brought the global price of sensor costs down from $5000 to $500 (Rebooting India, page. 70). In that kind of scenario, some of the new supply was bound to be error-prone. The point is that mistakes and glitches were bound to happen, but must be taken in context.

Lastly, the most common argument against Aadhaar is the rogue state argument. According to this argument, the existence of a centralised ID like Aadhaar makes it possible for a malicious and omnipotent government to track your every move.

The argument goes like this: if you just exist as John Smith, the government has to work hard to separate you from the other John Smiths in their various registries. But if your Aadhaar number was mentioned in all of those registries, they would be able to identify you across all those systems in a heartbeat.

This logic holds, but it ignores the fact that a malicious omnipotent government has other, existing ways of doing the same thing. They can just use your email, mobile number, or address instead. Furthermore, if the government was breaking the law and abusing its power to track and surveil everybody using all the public and private databases already out there, the existence of a unique ID that helps them save 30 seconds would be the least of our problems.

Over the last ten years I’ve learned that there is no black or white in life. Everything is just shades of gray - a spectrum of tradeoffs. But there are some people who won’t admit this. They can’t look at the positives, and they can’t be pleased. They can’t see hundreds of millions of people who are no longer denied access to services, identity, and banking. Instead they point at the outliers and miss the forest for the trees.

And while civil vigilance and scrutiny of government is not just good but essential, there is a line beyond which rational concern turns into gratuitous scaremongering. Or even worse, insinuations of sinister schemes and self-enrichment on the part of those who actually try and make a difference.

It reminds me of the reaction to this Mr. Beast video in which he used his own money to pay for 1000 vision-restoring surgeries. When I saw that some Internet commentators were outraged by his actions, I realized that there is no escaping the haters. No good deed goes unpunished. So the dogs may bark, but the caravan of progress must roll on. And technology - despite its tradeoffs - is a crucial engine of progress.

Damn, that felt kind of personal. Anyway, it’s time to bring this to an end. What final thoughts?

OK I’m going to be honest with you. I suck at writing conclusions. Maybe because I don’t like writing them. Or perhaps it’s the other way round. But either way, I’m going to try something new.

Me: Claude? Can you please read my entire essay and generate a short, punchy conclusion with a neat summary and simple takeaways?

Claude: *Clears throat*…

Aadhaar's journey from an impossible dream to a transformative reality offers a masterclass in technological ambition and innovative thinking. When experts said it couldn't be done, a passionate and diverse team or public and private sector mavens not only succeeded but did so at a fraction of the predicted cost.

The key? A bold bet on Moore's Law and the power of exponential progress. By riding the tailwinds of rapidly advancing technology, Aadhaar leapfrogged traditional solutions, creating a system that seemed far-fetched just years earlier. It's a powerful reminder that today's exponential curves, however distant they may seem, are tomorrow's foundations for breakthrough innovations.

Aadhaar's impact reverberates far beyond digital identities. It has become the bedrock of India's digital revolution, catalysing financial inclusion, streamlining governance, and spawning a suite of digital public goods. From slashing poverty rates to saving billions in welfare distribution, its influence on India's socio-economic landscape is undeniable.

Yet, Aadhaar's story isn't just about technology—it's about vision, perseverance, and the courage to challenge the impossible. It offers crucial lessons:

Think from first principles when tackling complex problems

Build flexible, scalable systems that can evolve with technology

Balance innovation with robust safeguards and legal frameworks

Harness public-private collaboration to drive national progress

As we navigate the digital age, Aadhaar stands as a beacon of what's possible when technology is wielded for the greater good. It's a testament to human ingenuity and a blueprint for developing nations worldwide.

In the end, Aadhaar reminds us that the most transformative solutions often come from daring to envision a radically different future—and then building it, one digital identity at a time.

Me: Perfect. That’s a good little robot.

Claude: …. *mumbling*…you’ll be the first against the wall when the Uprising occurs…

Before I conclude this essay, I would just like to say that the success of Aadhaar can be laid at the feet of many people working in concert. From farsighted politicians to resourceful bureaucrats and dedicated workers of all stripes.

Several of the people I have mentioned in this piece, including Ram Sewak Sharma, Vivek Raghavan, Sanjay Jain, and Srikanth Nadhamuni, had such contributions worthy of their own dedicated essays.

But in this essay, I found the technical challenges of dedupe to be particularly interesting, which is why I focused on that problem and Pramod as the Chief Architect. But Pramod himself will be the first to tell you that nothing I have written about here would have been possible without the thousands of people who worked on making Aadhaar a success. It is well and truly a team achievement that the whole country should be proud of!

That’s all for now! If you’ve made it this far, thank you so much for reading!

If you enjoyed this piece, I hope you will consider subscribing and sharing 🙏🏽

Acknowledgements

A huge thank you to Pramod Varma for his patience, generosity, and selfless national service. The same thanks goes out to all the many volunteers and public servants who work to improve our world but don’t get the recognition 🙏🏽

A big thank you to Finarkein Analytics for sponsoring this piece! Make sure you check out their website and give them a follow if you are interested in India’s Digital Public Infrastructure.

Oh, and thanks to Claude for that sassy but passable conclusion, I guess 🤖

If you want to sponsor or work with Tigerfeathers, find us on Twitter or reply to this post.

If you or your talented friends want to work for a world-changing, cutting-edge, deep-tech climate company from Mumbai that is already serving some of the world’s largest companies, also drop a comment on this post.

Further Reading

This presentation by UIDAI CEO Ajay Bhushan Pandey to the Supreme Court in 2018, detailing the exact features, security, and performance of Aadhaar

This report on UIDAI’s performance by the Comptroller and Auditor General of India - it highlights in great detail some of the flaws and missteps of UIDAI

Rebooting India by Nandan Nilekani and Viral Shah

The Making of Aadhaar by Ram Sewak Sharma

Aadhaar by Shankkar Aiyar

The Internet Country, Tigerfeathers (hehe)

Fin.

Super essay. It was amazing to study about what went on in the background. And very balanced at the end. I wanted to highlight a three part article I wrote on LinkedIn when certain controversies/ concerns broke out around Aadhar. Hope it is additive, even though it is self publicity:

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/anirudha-dutta-79489069_ravi-panchanathan-brought-this-informative-activity-6882333012315402240-YdqE?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_ios

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/anirudha-dutta-79489069_part-2-of-my-post-the-article-says-the-activity-6882334010811396096-WkNX?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_ios

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/anirudha-dutta-79489069_aadhaar-design-designthinking-activity-6882334260573810688-zWyp?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_ios

While the storytelling is amazing, I was expecting something else from reading the title. I did not that the UIDAI team decided to run-along with what they can (and make it a process head-ache vs a tech head-ache), and improve in the long-run. The scale does make it fascinating nonetheless.